Champaran: How Gandhi's Journalistic Traits And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gandhi Wields the Weapon of Moral Power (Three Case Stories)

Gandhi wields the weapon of moral power (Three Case Stories) By Gene Sharp Foreword by: Dr. Albert Einstein First Published: September 1960 Printed & Published by: Navajivan Publishing House Ahmedabad 380 014 (INDIA) Phone: 079 – 27540635 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.navajivantrust.org Gandhi wields the weapon of moral power FOREWORD By Dr. Albert Einstein This book reports facts and nothing but facts — facts which have all been published before. And yet it is a truly- important work destined to have a great educational effect. It is a history of India's peaceful- struggle for liberation under Gandhi's guidance. All that happened there came about in our time — under our very eyes. What makes the book into a most effective work of art is simply the choice and arrangement of the facts reported. It is the skill pf the born historian, in whose hands the various threads are held together and woven into a pattern from which a complete picture emerges. How is it that a young man is able to create such a mature work? The author gives us the explanation in an introduction: He considers it his bounden duty to serve a cause with all his ower and without flinching from any sacrifice, a cause v aich was clearly embodied in Gandhi's unique personality: to overcome, by means of the awakening of moral forces, the danger of self-destruction by which humanity is threatened through breath-taking technical developments. The threatening downfall is characterized by such terms as "depersonalization" regimentation “total war"; salvation by the words “personal responsibility together with non-violence and service to mankind in the spirit of Gandhi I believe the author to be perfectly right in his claim that each individual must come to a clear decision for himself in this important matter: There is no “middle ground ". -

Agrarian Movements in Bihar During the British Colonial Rule: a Case Study of Champaran Movement

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Research International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Research ISSN: 2455-2070; Impact Factor: RJIF 5.22 Received: 06-09-2020; Accepted: 17-09-2020; Published: 07-10-2020 www.socialsciencejournal.in Volume 6; Issue 5; 2020; Page No. 82-85 Agrarian movements in Bihar during the British colonial rule: A case study of Champaran movement Roma Rupam Department of History, Tilka Manjhi Bhagalpur University, Bhagalpur, Bihar, India Abstract British colonial rule in India brought about transformation in every area of Indian social, political and economic life. The impact of British colonial rule on agrarian society was decisive. The policy of colonial rule had changed the agrarian structure in India. The colonial rule had also developed new mechanisms to interact with peasants. Both new agrarian structure and new mechanisms to interact with peasants divided the agrarian society into the proprietors, working peasants and labourers. The roots of exploitation and misery of majority of people in agrarian society can be traced in the land tenure systems. The land relations were feudal in the permanent settlement areas. In the areas of Mahalwari and Ryotwari areas, the land had passed to absentee moneylenders, Sahukars and businessman due to large scale peasants’ indebtedness. This paper will give an overview of some of the major agrarian movements and their impact on the agrarian society. The peasants had been the worst sufferers of British Raj in colonial India. Because of the nature of land revenue system and its impact on agrarian society, the agrarian movements emerged in many parts of India. -

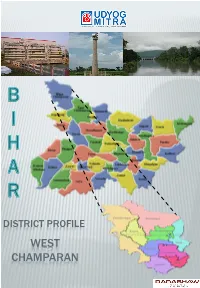

West Champaran Introduction

DISTRICT PROFILE WEST CHAMPARAN INTRODUCTION West Champaran is an administrative district in the state of Bihar. West Champaran district was carved out of old champaran district in the year 1972. It is part of Tirhut division. West Champaran is surrounded by hilly region of Nepal in the North, Gopalganj & part of East Champaran district in the south, in the east it is surrounded by East Champaran and in the west Padrauna & Deoria districts of Uttar Pradesh. The mother-tongue of this region is Bhojpuri. The district has its border with Nepal, it has an international importance. The international border is open at five blocks of the district, namely, Bagha- II, Ramnagar, Gaunaha, Mainatand & Sikta, extending from north- west corner to south–east covering a distance of 35 kms . HISTORICAL BACKGROUND The history of the district during the late medieval period and the British period is linked with the history of Bettiah Raj. The British Raj palace occupies a large area in the centre of the town. In 1910 at the request of Maharani, the palace was built after the plan of Graham's palace in Calcutta. The Court Of Wards is at present holding the property of Bettiah Raj. The rise of nationalism in Bettiah in early 20th century is intimately connected with indigo plantation. Raj Kumar Shukla, an ordinary raiyat and indigo cultivator of Champaran met Gandhiji and explained the plight of the cultivators and the atrocities of the planters on the raiyats. Gandhijii came to Champaran in 1917 and listened to the problems of the cultivators and the started the movement known as Champaran Satyagraha movement to end the oppression of the British indigo planters. -

University Grants Commission, New Delhi Recognized Journal No

University Grants Commission, New Delhi Recognized Journal No. 41311 ISSN: Print: 2347-5021 www.research-chronicler.com ISSN: Online: 2347-503X Addressing a Generation in Transition A Reading of Babu Brajakishore Prasad’s Presidential Address Bihar Students’ Conference, Chapra, 1911 Sunny Kumar Research Scholar, Department of History, B.R.A.B.U. Muzaffarpur, (Bihar) India Abstract The presidential address of Babu Brajkishore Prasad at the 1911 session of the sixth Bihar Students’ Conference—which took place annually during Dasahara1 period-- needs to be seen in its transitional, historical context. First of all, the speech takes place in 1911, when one of the most important missions of Babu Brajkishore Prasad’s public life and that of his other eminent contemporaries from Bihar, was about to become a reality. The mission, of course, was the carving out of Bihar from Bengal and making it a separate province. The issue of Bihar was settled with the Delhi Durbar proclamation in December 1911, cancelling the Partition of Bengal as announced in 1905. The separation of Bihar from Bengal was a great historical feat as it freed the Hindi-speaking areas of Bengal from one layer of colonial and cultural subjugation and allowed for them a socio-political identity and space in the newly emerging national consciousness under the one geographical, economic, social and cultural entity called Bihar, then written as Behar. Key Words : Generation, Transition, Province, Consensuses, Subjection However, the movement for the creation of Readers of Bryce’s American Bihar was not an easy task for its leaders. Commonwealth are no doubt aware that In fact, those espousing the cause of Bihar there exists in the United States a strong were seen to be moving in the opposite state patriotism, which subsists side by direction of the clarion call for national side with federal patriotism. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Dr. Awadhesh Kumar H.o.D & Assistant Professor Division of Economics & Agriculture Economics A N Sinha Institute of Social Studies, Patna Mobile : 98358 89013 e– mail : [email protected] Specialisation : (a) Rural Economics (b) Industrial Economics Experience : About 21 years’ Teaching and Research experience in different projects related to Social Issues and Rural Economics. Education & Training: ► Post Graduation in Economics from Patna University, Patna in 1997 Specialization in Rural Economics, Industrial Economics Grade – Second Class ► Qualified UGC – NET in June 1999 (Economics) ► PhD in Economics, B.R. Ambedkar Bihar University, Dec. 2019 Positions Held (in descending order) : (a) Assistant Professor, Division of Economics, A.N. Sinha Institute of Social Studies, Patna from August 2010 till date (11 years +) (b) Research Associate in Bihar Institute of Economic Studies, Patna from October 2003 to July 2010 (7 years+) (c) Lecturer (Ad-hoc) in Economics in B.N. College, Patna from October 2000 to September 2003 Skill : (a) Policy analysis for rural development, livelihood issues and tribal and SC / ST affairs (b) Collection, compilation and interpretation of statistical data Professional Experience and Achievement : ► August 2010 till date as Assistant Professor, Division of Economics, A.N. Sinha Institute of Social Studies, Patna (a) Member of national level seminars from time to time (b) Member of Purchase Committee (c) Coordinator of Support Programme for Urban Reforms in Bihar under DFID Publication 1. I have written an Article entitled, “Indian Agriculture in Economic Growth : An Evaluation” in the Indian Journal –The Hindustan Review, p.57-59, Vol. 32, No. 30, April- June 2008. -

Aman Sir Wifistudy Use Code Liveaman on Unacademy

AMAN SIR WIFISTUDY(OFFICIAL) AMAN SIR WIFISTUDY USEUSE CODE CODE “AMAN LI11V”E ONAMAN UNACADEMY ON& GET UNACADEMY 10% DISCOUNT AMAN SIR WIFISTUDY(OFFICIAL) DAILY FREE SESSIONS AMAN SIR WIFISTUDY USEUSE CODE CODE “AMAN LI11V”E ONAMAN UNACADEMY ON& GET UNACADEMY 10% DISCOUNT AMAN SIR WIFISTUDY(OFFICIAL) AMAN SIR WIFISTUDY USEUSE CODE CODE “AMAN LI11V”E ONAMAN UNACADEMY ON& GET UNACADEMY 10% DISCOUNT AMAN SIR WIFISTUDY(OFFICIAL) AMAN SIR WIFISTUDY USELIVEAMANUSE CODE CODE “AMAN LI11V”E ONAMAN UNACADEMY ON& GET UNACADEMY 10% DISCOUNT AMAN SIR WIFISTUDY(OFFICIAL) Q1. With reference to the Indian freedom struggle, which one of the following is the correct chronological order of the given events? भारतीय वतंत्रता संग्राम के संदभभ मᴂ, नि륍िलिखित मᴂ से कौि सा घटिाओं के सही कािािुक्रलमक क्रम है? a) Partition of Bengal - Lucknow Pact - Surat split of congress / बंगाि का ववभाजि - िििऊ समझौता - सूरत कांग्रेस का ववभाजि b) Partition of Bengal - Surat split of congress - Lucknow Pact / बंगाि का ववभाजि - कांग्रेस का सूरत ववभाजि - िििऊ संधि c) Surat split of Congress - Partition of Bengal - Lucknow Pact / कांग्रेस का सूरत ववभाजि - बंगाि ववभाजि - िििऊ संधि d) Surat split ofA congressMAN - Lucknow SIR Pact W -I PartitionFIST ofUDY Bengal / कांग्रेस का सूरत ववभाजि - िििऊ समझौता - बंगाि का ववभाजि USEUSE CODE CODE “AMAN LI11V”E ONAMAN UNACADEMY ON& GET UNACADEMY 10% DISCOUNT AMAN SIR WIFISTUDY(OFFICIAL) Q1. With reference to the Indian freedom struggle, which one of the following is the correct chronological order of the given events? भारतीय वतंत्रता संग्राम -

Nationalism Gandhian Phase

Unit - 8 Nationalism: Gandhian Phase Learning Objectives To acquaint ourselves with Gandhian phase of India’s struggle for independence Gandhi’s policy of ahimsa and satyagraha tried and tested for mobilisation of the masses in India Non-violent struggles in Champaran and against the Rowlatt Act The Non-Cooperation Movement and its fallout Emergence of radicals and revolutionaries and their part in the freedom movement Launch of Civil Disobedience Movement Issue of separate electorate and the signing of Poona Pact First Congress Ministries in the provinces and circumstances leading to the launch of Quit India Movement Communalism leading to partition of sub-continent into India and Pakistan Introduction violent methods to mobilise the masses and mount pressure on the British. In this lesson Mahatma Gandhi arrived in India in 1915 we shall see how Gandhi transformed the from South Africa after fighting for the civil Indian National Movement. rights of the Indians there for about twenty years. He brought with him a new impulse Gandhi and Mass to Indian politics. He introduced satyagraha, 8.1 Nationalism which he had perfected in South Africa, that could be practiced by men and women, young (a) Evolution of Gandhi and old. As a person dedicated to the cause Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was born of the poorest of the poor, he instantly gained on 2 October 1869 into a well to do family in the goodwill of the masses. Before Gandhi, Porbandar, Gujarat. His father Kaba Gandhi the constitutionalists appealed to the British was the Diwan of Porbandar and later became sense of justice and fair play. -

1. Letter to Lilavati Asar 2. Letter to Prabhavati1

1. LETTER TO LILAVATI ASAR POONA, August 30, 1945 CHI. LILI, I do not remember having answered your letter. Just now, after the prayer, I have taken out the old letters. This is just to tell you that I think of you. Continue your studies and pass. Do not lose courage. Do not spoil your health. There is no time to write more. Sardar’s treatment is going on. I am well. Blessings from BAPU From a photostat of the Gujarati: C.W. 10206. Courtesy: Lilavati Asar 2. LETTER TO PRABHAVATI1 POONA, August 30, 1945 CHI. PRABHA, I do not at all remember whether I have written to you. Your letter of the 1st is lying in front of me. I am writing this after the morning prayer. I hope you keep good health. You may come when you can. Just now I shall have to stay with Sardar in Poona. I may have to be here for three months. After that I shall be touring. You should stay in the Ashram. If there is suitable work for you there and you enjoy peace of mind and keep good health, settle down there. Do as you please. How is Father? Blessings from BAPU From a photostat of the Gujarati: G.N. 3579 1 The letters are in the Devanagari script.S VOL. 88 : 30 AUGUST, 1945 - 6 DECEMBER, 1945 1 3. LETTER TO PRABHAVATI1 August 30, 1945 CHI. PRABHA, A letter from Priyamvada is enclosed. I think you should join it2 Get yourself enrolled. About the work, we shall see after you have rested in the Ashram. -

THE GANDHI STORY in His Own Words

THE GANDHI STORY in his own words Condensed and Compiled by Mahendra Meghani From M. K. Gandhi’s two books An Autobiography and Satyagraha in South Africa LOK'MILAP TRUST TO Charles F. Andrews (1871-1940) The greatest interpreter of Gandhi to the whole Western world, beloved of both Gandhi and Tagore FtiMsfoi by Gopal Meghani Lok'Milap Trust 364001 India P.Q,Box 23 (Sardamagar), Bhavnagar r e-mail: lokmilaptxustZOOC (ft yahoo.com Phone: +9 1 278 2566 402, 2566 566 iMyrnt & Typeset by Apurva Ashar, Ahmcdabad, India Phone: +91 2717 215590 * Email: [email protected] Printed Riddhish Printers, Ahmed abad, India Phone; +91 79 2562 0239 Btjok-bmdmg Kumar Binders, Ahmedabad, India Phone: +91 79 2562 4964 Intemcitforkii edition March 2009; 5,000 copies Pages; 12+220+24 (photographs) = 256 R 50 [postage extra] $10 [including overseas airmail postage] Gandhi and Tagore: two faces of modern India. It was an Englishman who was the link between these two great representatives of modem India: the ascetic and the bard. Few felt their joint impact more sensitively than the saintly Englishman, C. F. Andrews. Let him estimate them whom he loved so well: completely “I have never in my whole life met anyone so under- satisfying the needs of friendship and intellectual standing and spiritual sympathy as Tagore. Side by side poet 1 have had the supreme with the friendship with the , His happiness of a friendship with Mahatma Gandhi. as character, in his own way, is as great and as creative religious that of Tagore. However, it has about it an air of that modem. -

The Making of the National Movement: 1870S--1947

History - Class 8 Our Past - III Chapter 9: The Making of the National Movement: 1870s--1947 Activity:1 Question: From the beginning, the Congress sought to speak for, and in the name of, all the Indian people. Why did it choose to do so? Answer: It chose to do so because it had to establish itself as an all-India organization. Otherwise, it would not ful¤ll its basic purpose. This was because the establishment of the Indian National Congress was the result of the need felt for an all-India organization of educated Indians since 1880. Activity:2 Question: What problems regarding the early Congress does this comment highlight? Answer: This comment highlights the problems of early Congress in the following ways: The leaders of early Congress were rich and often engaged in their personal work. They did not take much interest and devote su¢cient time to the organization. Activity:3 Question: Find out which countries fought the First World War. Answer: The First World War (1914-1918) involved more than 100 countries. The two sides of the war were the Allied Powers and the Central Powers. The Allies were led by Great Britain, France, Russia, and Italy. The central powers were led by Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire. Activity:4 Question: Find out about the Jallianwala Bagh massacre. What is Jallianwala Bagh? What atrocities were committed there? How were they committed? Answer: On the day of 13th April 1919, many people gathered in a closed space at Jallianwala Bagh in Amritsar city. General Dyre opened ¤re upon these innocent citizens who included women and children too. -

Evolving Horizons

ISSN : 2319 - 6521 EVOLVING HORIZONS AN INTERDISCIPLINARY INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF EDUCATION, HUMANITIES, SOCIAL AND BEHAVIORAL SCIENCES (A PEER REVIEWED JOURNAL) Volume 8 November 2019 Satyapriya Roy College of Education (Post Graduate Govt. Aided Teacher Education Institute) Kolkata ‐ 700 064 www.satyapriyaroycollege.in EVOLVING HORIZONS AN INTERDISCIPLINARY INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF EDUCATION, HUMANITIES, SOCIAL AND BEHAVIORAL SCIENCES (A Peer Reviewed Journal) Volume 8 November 2019 ISSN : 2319 - 6521 Satyapriya Roy College of Education (Post Graduate Govt. Aided Teacher Education Institute) 1 The Evolving Horizons is a peer reviewed international journal published annually by the Satyapriya Roy College of Education and devoted to the advancement and dissemination of the fundamental and applied knowledge of various subjects in an accessible form to professional colleagues who have a common interest in the fields in this country and abroad. © Satyapriya Roy College of Education. All rights are reserved. No part of this may be reproduced in any material form including photocopying or storing it in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidently to some other use of this publication without the written permission of the copyright owner except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act. Requests for Copyright owner’s permission to reproduce any part of this publication should be addressed to the publisher. Editor: Dr. Dipak Kumar Kundu The journal is issued annualy on the month of November Annual -

Raj Kumar Shukla

Raj Kumar Shukla March 27, 2021 In News: Department of Posts has issued a Commemorative Postage Stamp on Rajkumar Shukla About Raj Kumar Shukla Raj Kumar Shukla was born on 23rd August 1875 in Satwaria village of Champaran in Bihar. During the 31st session of the Congress in Lucknow in 1916, Gandhiji met Raj Kumar Shukla, a representative of farmers from Champaran, who requested him to come and see for himself the miseries of the indigo ryots (tenant farmers) there. Raj Kumar Shukla convinced Mahatma Gandhi to visit Champaran. Mahatma Gandhi arrived in Champaran with his team of eminent nationalists Rajendra Prasad, Anugrah Narayan Sinha, Brajkishore Prasad and the Champaran Satyagraha began. He rose to fame for his close association with Gandhiji during the Champaran Satyagraha. Champaran Satyagraha The Champaran peasant movement was Mahatma Gandhi’s first satyagraha in India When Gandhiji The Champaran peasant movement was launched in 1917-18. Its objective was to create awakening among the peasants against the European planters. Gandhiji studied the grievances of the Champaran peasantry. The peasants opposed not only the European planters but also the jamindars. Cause of Satyagraha The introduction of synthetic dye, the demand of indigo decreased which led the zamindars or planters to reduce their burden by increasing the rent burden on the peasants, which added to the existing plight of the peasants. As the demand of indigo declined, peasants demanded to shift to other crops on the same land. Even after the First World War, demand and supply of synthetic fell, the planters did not decrease the rent- burden and compensation.