Sikkim University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Select Bibliography I I I I

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY PRIMARY SOURCES: Books Gandhi M. K., Constructive Programme: Its Meaning and Place, I Ahmedabad, Navajivan, 1941. Gandhi, M. K., An Autobiography or the Story of MJ Experiments with Truth, Ahmedabad, Navajivan Publishing HoJse, 1927. I I Gandhi, M. K., Hind Swaraj or Indian Home Rule, Rev. ed. I Ahmedabad, Navajivan, 1939. I Gandhi, M. K., Satyagraha in South Africa, Ahmedabad, Navajivan, 1938. I Gandhi, M. K., Satyagraha Ashram Ka Itihas (In I Hindi), Translated from the Original in Gujarati by Ramna!rayan Chaudhuri, Ahmedabad, Navajivan, 1948. ! I Gandhi, M. K., Collected Works OF MAHATJ11A GANDHI, THE I PUBLICATIONS DIVISION MINISTRY OF INFORMATION AND I BROADCASTING GOVERNMENT OF INIDA\ 100 Vols. Delhi, 1958-1994. I I Gandhi, M. K., Delhi Diary, Prayer speeches from :10.9.47 to 30.1.48, Ahmedabad, Navajivan, 1948. Gandhi, M. K., From Yeravda Mandir: Ashtam Observances, Translated from the original Gujarati by ValjJ Govindji Desai, 3rd ed. Ahmedabad, Navajivan, 1945. ! ' I Gandhi, M. K., Gandhi's Health Guide, California, The Crossian Press, 2000. Gandhi, M. K., India's Case for Swaraj: Being Select Speeches, Writings, Interviews etc. of Mahatma Gandhi in England and India, September, 1931 to January 1932,!2nd ed., edited by Waman P. Kabodi, Bombay, Yeshanand, 1932. I Gandhi, M. K., Key to Health, Translated byi Sushila Nayyar, Ahmedabad, Vavajivan, 1948. I Gandhi, M. K., Mahatma Gandhi the essential writings Oxford World's Classics, J.; M. Brown, Oxford University PreJs, 2008. I I Gandhi, M. K., Non-violence in Peace and ;.var, Ahmedabad, Navajivan, 1942. Gandhi, M. K., Teaching of Mahatma Gandhi, Edited by Jag Parvesh Chander, Lahore, The Indian Printing Works, /1945. -

Vijay Pratap

COMPILATION OF ARTICLES WRITTEN BY VIJAY PRATAP COMPILATION OF ARTICLES WRITTEN BY VIJAY PRATAP ENGLISH Printed on 13 December 2017 1 Printed on 13 December 2017 COMPILATION OF ARTICLES WRITTEN BY VIJAY PRATAP CONTENT LIST ARTICLES Page No. 1. Elections in India and their Impact on Weaker Sections 1-7 2 Danger of the Emergence of Inferiority Complex Pessimism 8-10 too 3 Changing Contours of Dalit Politics 11-14 4 Bahujan Wants Active Participation 15-17 5 Independent Dalit role not feasible in Bihar 18-20 6 The Context of the State Assembly Elections: Some Reflections 21-25 7 Lest We Lose the War 26-29 8 Excerpts from a letter to a friend on the future of Vasudhaiva 30-34 Kutumbakam 9 A Forum of Dialogues on Global Responsibility Towards 35-39 Democracy 10 The ‘Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam’ Initiative 40-42 11 A Brief Note on “India - Central Asia Dialogue” 43-45 12 Notes on Voluntarism 46-48 13 Samvaad: A Personal of Journey of Discovering Dialogue as a 49-53 New Tool for Intervention 14 Victim, Perpetrator and Innocent Spectator: Introspecting 54-56 about Terrorism 15 Politics of Right to Information 57-60 2 Printed on 13 December 2017 COMPILATION OF ARTICLES WRITTEN BY VIJAY PRATAP 16 A Dialogue on Democracy 61-67 17 Poverty in India – An Overview 68-78 18 States and Democracy in South Asia 79-80 19 Ten Dialogues on "Policy Interventions for Consolidation of 81-82 Democracy" 20 Conversations on Democracy - Anil Bhattarai and Vijay 83-86 Pratap 21 Corruption and Communalism: Anti-Democratic Elements of 87-92 Indian Politics- Vijay Pratap 22 Towards North-South Solidarity : Some Challenges for 93-95 Building North-South Solidarity - Vijay Pratap 23 The Urgency of Dialogues on Democracy - Anil Bhattarai and 96-97 Vijay Pratap 24 Minorities and Democracy 98-99 25 Some Reflections on Funding and Voluntarism- Vijay Pratap; 100-103 Assisted by G. -

The Mountain Path Vol. 22 No. 4, Oct 1985

VOL. 22 No. IV OCTOBER 1985 THE MOUNTAIN PATH Editorial Board (A QUARTERLY) Sri K.K. Nambiar Mrs. Lucy Cornelssen "Arunachala! Thou dost root out the ego of those who meditate on Thee in the Smt. Shanta Rungachary heart. Oh Arunachala!" Dr. K. Subrahmaniam — The Marital Garland of Letters, verse 1 Sri A.R. Natarajan Vol. 22 OCTOBER 1985 No. 4 Publisher T.N. Venkataraman CONTENTS President, Board of Trustees, Page Sri Ramanasramam EDITORIAL: Ramana's Fate Tiruvannamalai — A.R. Natarajan ... 225 Two Decades of The Mountain Path . 228 Managing Editor Surrender V. Canesan — David Godman ... 231 A Guided Tour of Heaven II Letters and remittances should —• Douglas Harding . 235 be sent to : A Station Passed Through (Chapter II) The Managing Editor, — Arthur Osborne . 239 ''THE MOUNTAIN PATH", The Speciality of Ramana and His Teachings Sri Ramanasramam, P.O., — Prof. N.R. Krishnamoorthy Iyer . 241 Tiruvannamalai—606^603 S. India. Morality and Self Knowledge: in the light of the Life and the Teachings of Bhagavan Sri Ramana Annual Subscription — Michael lames . 242 How I Came to Bhagavan Sri Ramana INDIA Rs. 15 — Gobindram H. Daswani ... 250 FOREIGN £4.00 $8.00 Sri Bhagavan's Introduction to Vivekachudamani Life Subscription — Jr. by Sadhu Om and Michael lames . 252 Subramania Bharati: A God-Centred Poet Rs.150 £35.00 $70 — Dr. K. Subrahmanian . 259 Noble Ramana Single Copy — V. Ganesan . 261 Rs.4.00 £1.20 $2.50 Some Impressions of Sri Ramana Maharshi — Swami Ritajananda . 267 IA Precious Relic . 269 I'Turiya' — The Natural State Is it true Silence to rest — N.N. -

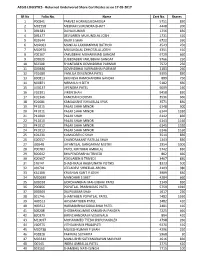

AEGIS LOGISTICS - Returned Undelivered Share Certificates As on 17-05-2017

AEGIS LOGISTICS - Returned Undelivered Share Certificates as on 17-05-2017 SR No Folio No. Name Cert No. Shares 1 P00841 PARVEZ HORMUSJI DAROGA 5751 830 2 M01558 MEENAXI SURENDRA BHATT 4448 200 3 D01681 DAYALKUMAR 1756 830 4 D01477 DEVILABEN MUKUNDLAL JOSHI 1731 410 5 R02644 RAJIV S SHAH 6722 260 6 M02063 MANILAL LAXMANBHAI RATHOD 4523 250 7 M00970 MUKUNDLAL CHHOTALAL JOSHI 4351 410 8 Y00107 YAKUBBHAI MUHAMMAD GANGAT 9729 660 9 Z00039 ZUBEDABEN YAKUBBHAI GANGAT 9766 250 10 S02308 SHANTABEN GOVINDBHAI PARMAR 7572 250 11 G00486 GOVINDBHAI VARWABHAI PARMAR 2183 260 12 V01680 VANLILA DEVENDRA PATEL 9395 830 13 B00813 BHUNESH RAMCHANDRA GANDHI 889 750 14 N00871 NIRMALA H SETH 5182 660 15 U00137 UPENDRA PATEL 9009 160 16 V02301 VIREN SHAH 9458 830 17 K01346 KANCHAN D DOSHI 3536 660 18 K01681 KAMALKANT ISHVARLAL VYAS 3571 830 19 P41015 PALAK SHAH MINOR 6148 900 20 P41011 PALAK SHAH MINOR 6144 1330 21 P41009 PALAK SHAH 6142 830 22 P41010 PALAK SHAH MINOR 6143 1160 23 P41012 PALAK SHAH MINOR 6145 1330 24 P41013 PALAK SHAH MINOR 6146 1160 25 K01230 KUMUDBEN C SHAH 3514 830 26 C00557 CHANDRAKANT RATILAL SHAH 1343 830 27 J00548 JAYANTILAL GANGARAM MISTRY 2954 1000 28 P00783 PATEL KIRITBHAI AMBALAL 5742 830 29 B00642 BHUPENDRABHAI TRIVEDI 862 660 30 K00967 KOKILABEN B TRIVEDI 3467 830 31 S10141 SHASHIKALA RAGHUNATH POTNIS 8323 500 32 L00702 LEELADEVI SHREELAL ARORA 4103 980 33 K61108 KRUSHAN KANT V JOSHI 3989 830 34 M00690 MANOHAR S SHET 4284 660 35 G00338 GORDHANBHAI MAHIJIBHAI PATEL 2149 830 36 P00866 POPATLAL PRABHUDAS PATEL 5759 1910 37 D00569 -

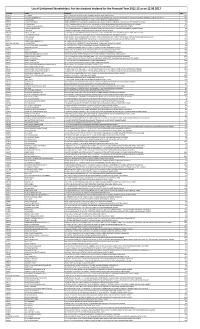

For the Dividend Declared for the Financial Year 2011-12 As on 12.09.2017

List of Unclaimed Shareholders: For the dividend declared for the Financial Year 2011-12 as on 12.09.2017 FOLIO NO NAME ADDRESS AMT A17671 A C SRAJAN 66 LUZ CHURCH ROAD MYLAPORE CHENNAI CHENNAI,TAMIL NADU,600004 360 D00252 A DHAKSHINAMOORTHY PARTNER V M C TRADERS STOCKISTS OF A C LTD 6/10 MARIAMMAN KOIL RAMANATHAPURAM DT RAMANATHAPURAM RAMNAD,TAMIL NADU,623501 180 A02076 A JANARDHAN 8/1101 SESHAGIRINIVAS NEW ROAD COCHIN COCHIN ERNAKULAM,KERALA,682002 50 A02270 A K BHATTACHARYA UNITED COMMERCIAL BANK MATA ANANDA NAGAR SHIVALA HOSPITAL VARANASI U P VARANASI,UTTAR PRADESH,221001 50 A03705 A K NARAYANA C/O A K KESAUACHAR 451 TENTH CROSS GIRINAGAR SECOND PHASE BANGALORE BANGALORE,KARNATAKA,560085 50 P00351 A K RAMACHANDRAPRABHU 'PAVITRA' NO 949 24TH MAIN ROAD J P NAGAR II PHASE BANGALORE BANGALORE,KARNATAKA,560078 720 A17411 A KALPAKAM NARAYAN C/O V KAMESWARARAO 7-6-108 ENUGULAMALAL STREET SRIKAKULAM (A.P.) SRIKAKULAM,ANDHRA PRADESH,532001 36 A04366 A M DAVID 1 MISSION COMPOUND AJMER ROAD JAIPUR JAIPUR,RAJASTHAN,302006 50 M00394 A MURUGESAN 3 A D BLOCK V G RAO NAGAR EXTENSION KATPADI P O VELLORE N A A DT VELLORE NORTH ARCOT,TAMIL NADU,632007 46 A17672 A N VENKATALAKSHMI 361 XI A CROSS 29TH MAIN J P NAGAR I PHASE BANGALORE BANGALORE,KARNATAKA,560019 100 A04006 A NATARAJAN ACCOUNTANT THE NEDUNGADI BANK LN NORTH PARUR ERNAKULAM DIST NORTH PARUR NORTHPARUR ERNAKULAM,KERALA,683513 50 A17587 A P VASUDEV A 304, TEMPLE TREES APARTMENT JARAGANAHALLI KANAKAPURA ROAD BANGALORE,KARNATAKA,560078 200 A17757 A RADHA KRISHNAMURTHY 305 LAXMI BAI NAGAR NEW -

1. Letter to Lilavati Asar 2. Letter to Prabhavati1

1. LETTER TO LILAVATI ASAR POONA, August 30, 1945 CHI. LILI, I do not remember having answered your letter. Just now, after the prayer, I have taken out the old letters. This is just to tell you that I think of you. Continue your studies and pass. Do not lose courage. Do not spoil your health. There is no time to write more. Sardar’s treatment is going on. I am well. Blessings from BAPU From a photostat of the Gujarati: C.W. 10206. Courtesy: Lilavati Asar 2. LETTER TO PRABHAVATI1 POONA, August 30, 1945 CHI. PRABHA, I do not at all remember whether I have written to you. Your letter of the 1st is lying in front of me. I am writing this after the morning prayer. I hope you keep good health. You may come when you can. Just now I shall have to stay with Sardar in Poona. I may have to be here for three months. After that I shall be touring. You should stay in the Ashram. If there is suitable work for you there and you enjoy peace of mind and keep good health, settle down there. Do as you please. How is Father? Blessings from BAPU From a photostat of the Gujarati: G.N. 3579 1 The letters are in the Devanagari script.S VOL. 88 : 30 AUGUST, 1945 - 6 DECEMBER, 1945 1 3. LETTER TO PRABHAVATI1 August 30, 1945 CHI. PRABHA, A letter from Priyamvada is enclosed. I think you should join it2 Get yourself enrolled. About the work, we shall see after you have rested in the Ashram. -

Social and Political Thought of Mahatma Gandhi

Social and Political Thought of Mahatma Gandhi During his campaign against racism in South Africa and his involvement in the Congress-led nationalist struggle against British colonial rule in India, Mahatma Gandhi developed a new form of political struggle based on the idea of satyagraha or non-violent protest. He ushered in a new era of nation- alism in India by articulating the nationalist protest in the language of non- violence or ahisma, which galvanized the masses into action. Social and Political Thought of Mahatma Gandhi focuses on the principles of satyagraha and non-violence, and their evolution in the context of anti- imperial movements organized by Gandhi, looking at how these precepts underwent changes reflecting the ideological beliefs of the participants. The book focuses on the ways in which Gandhi took into account the views of other leading personalities of the era while articulating his theory of action, and assesses Gandhi and his ideology. Concentrating on Gandhi’s writings in Harijan, the weekly newspaper of the Servants of Untouchable Society, this volume offers a unique contextualized study of Gandhi’s social and political thought. Bidyut Chakrabarty is Professor in Political Science at the University of Delhi, India. Routledge studies in social and political thought 1 Hayek and After 8 Max Weber and Michel Hayekian liberalism as a research Foucault programme Parallel life works Jeremy Shearmur Arpad Szakolczai 9 The Political Economy of Civil 2 Conflicts in Social Science Society and Human Rights Edited by Anton van Harskamp G.B. Madison 3 Political Thought of André 10 On Durkheim’s Elementary Gorz Forms of Religious Life Adrian Little Edited by W.S.F. -

Interface of Cultural Identity Development

INTERFACE OF CULTURAL IDENTITY DEVELOPMENT www.ignca.gov.in INTERFACE OF CULTURAL IDENTITY DEVELOPMENT Edited by BAIDYANATH SARASWATI 1996 xxi+290pp. ISBN: 81-246-0054-6, Rs 600(HB) Contents It is the inaugural volume of the Culture and Development series, Foreword (Kapila Vatsyayan) comprising 23 presentations of Prologue (Francis Childe) a Unesco-sponsored meeting Introduction (Baidyanath Saraswati) of experts: 19-23 April 1993 at IGNCA, New Delhi. Highlightng 1. Interface of Science Consciousness and Identity (S.C. Malik) the basic distinctions that exist 2. Humanization of Development: A Theravada Buddhist between anthropocentric and Perspective (P.D. Premasiri) cosmocentric approaches to 3. Universal and Unique in Cross-cultural Interaction: A Paradigm the question of cultural identity Shift in Development Ideology (Lachman M. Khubchandani) and development, the authors reflect on what constitutes 4. Universality, Uniformity and Specificity: a View from a Developing culture and development Country (Anisuzzaman) not per se, but as an integral 5. Identity, Tribesman and Development (Mrinal Miri) holistic notion of culture and 6. Cultural Identity and Development in the Torres Strait lifestyle, culture and Islands (Leah Lui) development, culture and 7. Identity, Ownership and Appropriation: Aspects of Aboriginal region, culture and Australian Experience in Tertiary Education (Olga Gostin) linguistic/ecological identities, 8. Crisis of Cultural Identity in Mongolian Nomadic and how some of the viable Civilization (Otgonbayar) alternative development 9. Quest for Cultural Identity in Turkey: National Unity of Historical paradigms could be evolved Diversities and Continuities (Bozkurt Guven) from the convergence of mystical ancient insights and 10. Popular Culture and Arabesque Music in Turkey (Meral Özbek) modern science. -

Isbn Title Author Publisher Currency Mrpstock in Hand

ISBN TITLE AUTHOR PUBLISHER CURRENCY MRPSTOCK IN HAND 9781558598089 Jewelry By Joan Rivers Joan Rivers Abbeville Press PublishersUSD 35.00 25 9781864367515 Hidden Faces Of India Palani Mohan New Holland Rs. 1,195.00 25 9783980043403 Diamond grading Abc Verena pagal Robin & Son Bvba USD 45.00 25 9781554073801 The Pregnancy Bible Joanne Stone A Firefly Book $ 29.95 25 9781841813653 The Tarot Bible Hachette India A Godsfield Books Rs. 495.00 50 9781841811444 Zero Oil Thali A Complete Meal Without Oil Timothy Freke A Godsfield Books Rs. 795.00 0 9787116200799 Soulmate A Novel Of Eternal Love Deepak Chopra A Signet Book Rs. 295.00 100 9780349116853 Kipling Sahib Indian And The Making Of Rudyard KiplingCharles Allen Abacus Rs. 595.00 25 9780349115047 The Secret Lives Of The Dalai Lama Alexander Norman Abacus Rs. 495.00 25 9788189995010 Daughters of India Art and Identity Stephen P Huyler Mapin Publishing House Rs. 3,000.00 266 9780810958753 Mother Teresa A Life Of Dedication Raghu Rai Abhrams Rs. 2,000.00 27 9780810982468 The Song Of Krishna The Illustrated Bhagavad Gita Edwin Arnold Abhrams USD 16.95 400 9780810955363 Indian Painting The Great Mural Tradition Mira Seth Abhrams Rs. 3,500.00 25 9789351042440 I Am Malala Anoop Kamath Aether Books Rs. 295.00 0 9789351262893 Davyaprithvm Heaven on earth Rajdeep paul Aether books Rs. 295.00 5 9782226184047 Sujata Bajaj Lordre Du Monde Albin Rs. 2,500.00 25 9789382277071 On Hinduism Wendy Doniger Aleph Rs. 995.00 25 9789382277552 Exotic Aliens The Lion & The Cheetah In India Valmik Thepar Aleph Rs. -

Gandhi's Laboratory: the South African

International Journal of Research in Economics and Social Sciences (IJRESS) Vol. 6 Issue 9, September - 2016, pp 1~13 ISSN(o): 2249-7382 | Impact Factor: 6.225 , | Thomson Reuters ID: L-5236-2015 GANDHI’S LABORATORY: THE SOUTH AFRICAN YEARS Biplove Kumar,M.Phil Scholar, Department of History, Sikkim University, Gangtok, Sikkim When Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi entered the field of Indian politics in 1916, he had placed his concept of swaraj upon four pillars. They were: the end of untouchability, Hindu – Muslim unity, the principle for non-violence for freedom, and transformation of villages by spinning and other self-sustaining methods. These four pillars almost covered all the aspects, which were needed by the subcontinent to unite and fight for its independence. And these then set the paradigm of the political discourse in India for at least two decades since his return to India. This paradigm, it may be stressed, was not cultivated in a day, month or year;its prologue was his struggle in South Africa where he tried to erase the hardships of Asiatic people. Twenty one years and the legacy of the foreign land led to the evolution of Gandhi’s ideas in the social, political and religious fields.South Africa witnessed the provenience of a social and political reformer. In this sense, what Gandhi did to South Africa was less important than what South Africa did to him.1Witha law degree from London,Gandhi failed to set himself up as a lawyer in Bombay; he movedto South Africa in order to establish himself as a successful lawyer.Alien environment welcomed him as coolie (a derogatory term used for Indians in South Africa then) and not as a lawyer. -

Life Membership List from L01 to L 7091

L01 L08 H. M. PATEL I.C.S. RASIKLAL PHUNDILAL SHAH VALLABH VIDYANAGAR, VIA- ANAND, WEST JIMA PRAKASH ROAD, SHAHADA, DISTT- RAILWAY, GUJARAT DHULIA, MAHARASHTRA+ Contact: ----- Contact: ----- ----- ----- ANAND - 0, Gujrat DHULIA - 0, Maharashtra L03 L09 PRAMUKHLAL M PATEL N.C. SHAH FRIENDS HOME, VEER NARIMAN ROAD, SHAHADA, WEST KHANDESH, MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI- 400001 Contact: ----- Contact: ----- ----- ----- MUMBAI - 400001, Maharashtra WEST KHANDESH - 0, Maharashtra L05 L10 GIRDHAR LAL DAMODARDAS MADAN MOHAN MURAR KA REID ROAD, AHMADABAD, GUJARAT 7, LYONS RANGE P.O. BOX NO. 204 CALCUTA - 700001 Contact: ----- Contact: ----- ----- ----- AHMADABAD - 0, Gujrat CALCUTTA - 0, West Bengal L06 L1000 LAVE GIRDHAR LAL RAMESH NARAIAN MATHUR REID ROAD, AHMADABAD, GUJARAT 45, SUBHAS NAGAR, GANDHI COLONY, MUZAFFAR NAGAR (UP) Contact: ----- Contact: ----- ----- ----- AHMADABAD - 0, Gujrat MUZAFFAR NAGAR - 0, Uttar Pradesh L07 L1001 SHIBA PRASAD BANERJEE CHANAN SINGH RAMGARHIA 44, RAI BAHADUR SATISH, CHANDRA ROAD, PO- 1410/7, RAM NAGAR, LONI ROAD, SHAHDARA HOOGHLY BANDEL, WEST BENGAL- NEW DELHI-110032 Contact: ----- Contact: ----- ----- ----- HOOGLY - 0, West Bengal SHAHDARA - 0, Delhi L1002 L1008 JUTA OBEROI GURDIP SINGH SAHI C/O MADDENS HOTEL DELHI 3035, SECTOR 28-D, CHANDIGARH Contact: ----- Contact: ----- ----- ----- DELHI - 0, Delhi CHANDIGARH - 0, Chandigarh L1004 L1009 HABIB ULLAH KHAN BALRAJ SINGH GREWAL AT & P.O. BUTRAVA. DISTT. MUZAFFARNAGAR BXX-546, OPP. MUNNI LALA ATTA CHAKKI. (UP) GHUMAR MANDI, CIVIL LINES. LUDHIANA Contact: ----- Contact: ----- ----- ----- MUZFFARNAGAR - 0, Uttar Pradesh LUDHIANA - 0, Punjab L1005 L101 ASGHAR ALI KHAN MADHUSUDAN C. PAREKH VILL & P.O. BUTRAVA DISTT. MUZAFFARNAGAR C/O. RAJNAGAR SPG & WVG. MILLS LTD (UP) Contact: ----- Contact: ----- ----- ----- MUZAFFARNAGAR - 0, Uttar Pradesh AHMEDABAD - 0, Gujrat L1006 L1010 RAJ PAL SINGH MANN ASHOK NORONHA B-14, GEETANJALI ENCLAVE , MEHRAULI ROAD, E-1/42- AREA COLONY, S/O SHRI R.P. -

In Search of Gandhi's India

In Search of Gandhi’s India: The Teaching and the Learning of Non- Violence in a Globalized World Fulbright-Hays Group Studies Abroad Itinerary June 29-August 5, 2008 Day 0 Sat. June 28, 2008 710pm: Depart Chicago – AA 292 Day 1 Sun. June 29, 2008: Delhi 8:30pm: Arrive Delhi – AA 292, pickup / 1 hr Bharata/Bharatam Check in: The Hans Hotel – 8 nights / - India’s ancient www.hanshotels.com and true name, literally means Day 2 Mon. June 30: Delhi “obsessed with light” or simply, 8:00 am: Breakfast and Greetings “Enlightened.” 9:00 am: Leave for USEFI India is thus a 9:30 am: Welcome by USEFI Director Orientation and Fulbright Bharatiya State: a Researchers state of 10:30-11:30: Tea Break enlightenment 11:00 am: Opening Lecture beyond the “The Politics of Reading Gandhi,” Vinay Lal, dualism of Professor of History, UCLA and Director of UCLA secularism and Education Abroad religion, a trustee Program in Delhi consciousness of 1:00 pm: Lunch spiritual and 2-5 pm: Rest at hotel or Shopping humane traditions 5-7:30 pm: Tour I: New Delhi as National Capital: Rashtrapati Bhavan, of illumination, Sansad Bhavan, Secretariat – North & South Blocks, India not only the Gate, Colonial buildings distinctively 8:00 pm Dinner Indian traditions of realisation - Adivasi, Jaina, Buddhist, ‘Hindu’, Sikh and others but Day 3 Tues. July 1: Delhi also including the 7:30 am: Breakfast Abrahamic, 8:30 am: Leave for USEFI African, Chinese, 9 am: Lecture Egyptian and, all “Gandhi’s Ahimsa: A Riposte to Modern Nihilism,” Dilip mystical traditions Simeon, Historian and Director of Aman Trust, Delhi of spirituality 11-11:30 Tea - 11:30-1:30 Lecture Ramachandra “The Truth (Dharma) of Non-Violence,” Dr.