Special Issue of Gandhi Marg (January – March 2020) Call for Papers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Select Bibliography I I I I

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY PRIMARY SOURCES: Books Gandhi M. K., Constructive Programme: Its Meaning and Place, I Ahmedabad, Navajivan, 1941. Gandhi, M. K., An Autobiography or the Story of MJ Experiments with Truth, Ahmedabad, Navajivan Publishing HoJse, 1927. I I Gandhi, M. K., Hind Swaraj or Indian Home Rule, Rev. ed. I Ahmedabad, Navajivan, 1939. I Gandhi, M. K., Satyagraha in South Africa, Ahmedabad, Navajivan, 1938. I Gandhi, M. K., Satyagraha Ashram Ka Itihas (In I Hindi), Translated from the Original in Gujarati by Ramna!rayan Chaudhuri, Ahmedabad, Navajivan, 1948. ! I Gandhi, M. K., Collected Works OF MAHATJ11A GANDHI, THE I PUBLICATIONS DIVISION MINISTRY OF INFORMATION AND I BROADCASTING GOVERNMENT OF INIDA\ 100 Vols. Delhi, 1958-1994. I I Gandhi, M. K., Delhi Diary, Prayer speeches from :10.9.47 to 30.1.48, Ahmedabad, Navajivan, 1948. Gandhi, M. K., From Yeravda Mandir: Ashtam Observances, Translated from the original Gujarati by ValjJ Govindji Desai, 3rd ed. Ahmedabad, Navajivan, 1945. ! ' I Gandhi, M. K., Gandhi's Health Guide, California, The Crossian Press, 2000. Gandhi, M. K., India's Case for Swaraj: Being Select Speeches, Writings, Interviews etc. of Mahatma Gandhi in England and India, September, 1931 to January 1932,!2nd ed., edited by Waman P. Kabodi, Bombay, Yeshanand, 1932. I Gandhi, M. K., Key to Health, Translated byi Sushila Nayyar, Ahmedabad, Vavajivan, 1948. I Gandhi, M. K., Mahatma Gandhi the essential writings Oxford World's Classics, J.; M. Brown, Oxford University PreJs, 2008. I I Gandhi, M. K., Non-violence in Peace and ;.var, Ahmedabad, Navajivan, 1942. Gandhi, M. K., Teaching of Mahatma Gandhi, Edited by Jag Parvesh Chander, Lahore, The Indian Printing Works, /1945. -

A Page Abdul Gaffar Nagar 237 Aga Khan Palace 276 Ahmed, Moulvi

INDEX A B—contd. Page Page Abdul Gaffar Nagar 237 Bombay Swarajya Party 168 Aga Khan Palace 276 Bose, Sarat Chandra 29 3 Ahmed, Moulvi Raffiuddin 80 Bose, Subhash Chandra 290 Aiyar, C. P. Ramswami 15 Brelvi, S. A 278 Akhil Bharatiya Goraksha Mandal 181 Akut, V.S. 147 C Ali Mahomed 129 Ali Sayad Reza 173 Central Khilafat Committee 95, 138, 145, All India Congress Committee 13, 14, 168, 185 26, 82, 92, 167, 168, Chagla, M. C. 1 83 193, 273, 293. Chandavarkar, Narayan, Sir 12 All India Gou Seva Sangh 274, 301 Chaturvedi, Madan Mohan 244 All India Harijan Sewak Sangh 256 Chintamani, C. Y. 163 All India Hindustani Talimi 292 Cholkar, Moreshwar Ramcha- 259 Sangh. ndra, Dr. All India Home Rule League 16, 17, 81, Chhotani, Jan Mohmed 80 82 Chowdhary, Rambhuj Dutt 80 All India Khilafat Conference 86 Chunilal Dwarkadas 293 All India Muslim League 15,173 Cutchi Jain Association 63 All India Spinners' Association 275, 296 D All India Tilak Memorial 82 Altekar, M. D. 183 Damle, S. K. 161, 186 Andrews, C. F. 39, 80 Dastagir, Vastad Ghulam 159 Aney, M. S. 240 Dastane, W. V. 154,187 Ansari, M. A. 231 Dave, M. Rohit 286 Apte, L. J. 131 Deo, S. D. 161, 187, 293 Asar, Laxmi Purshottam 265 Deogirikar, T. R. 277 Asavle, R. S. 163 Desai, Bhulabhai J. 228 Avte, T. H. 161 Desai, Madhavbhai Haribhai 96, 187 Azad, Maulana Abul Kalam 106, 228, Deshmukh, Moreshwar Gopal. Dr. 3 266 Deshpande, G. B. 69, 89,172 Deshpande, S. V. 211 B Devdhar, G K. -

India's Naxalite Insurgency: History, Trajectory, and Implications for U.S

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 22 India’s Naxalite Insurgency: History, Trajectory, and Implications for U.S.-India Security Cooperation on Domestic Counterinsurgency by Thomas F. Lynch III Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for Complex Operations, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, and Center for Technology and National Security Policy. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the unified combatant commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community. Cover: Hard-line communists, belonging to the political group Naxalite, pose with bows and arrows during protest rally in eastern Indian city of Calcutta December 15, 2004. More than 5,000 Naxalites from across the country, including the Maoist Communist Centre and the Peoples War, took part in a rally to protest against the government’s economic policies (REUTERS/Jayanta Shaw) India’s Naxalite Insurgency India’s Naxalite Insurgency: History, Trajectory, and Implications for U.S.-India Security Cooperation on Domestic Counterinsurgency By Thomas F. Lynch III Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. -

N.G.M. College (Autonomous) Pollachi- 642 001

SHANLAX INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ARTS, SCIENCE AND HUMANITIES (A Peer-Reviewed, Refereed/Scholarly Quarterly Journal with Impact Factor) Vol.5 Special Issue 2 March, 2018 Impact Factor: 2.114 ISSN: 2321-788X UGC Approval No: 43960 International Conference on Contributions and Impacts of Intellectuals, Ideologists and Reformists towards Socio – Political Transformation in 20th Century Organised by DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY (HISTORIA-17) Diamond Jubilee Year September 2017 Dr.R.Muthukumaran Head, Department of History Dr.K.Mangayarkarasi Mr.R.Somasundaram Mr.G.Ramanathan Ms.C.Suma N.G.M. College (Autonomous) Pollachi- 642 001 Dr.B.K.Krishnaraj Vanavarayar President NGM College The Department of History reaches yet another land mark in the history of NGM College by organizing International Conference on “Contributions and Impacts of Intellectuals, Ideologists and Reformists towards Socio-political Transformation in 20th century”. The objective of this conference is to give a glimpse of socio-political reformers who fought against social stagnation without spreading hatred. Their models have repeatedly succeeded and they have been able to create a perceptible change in the mindset of the people who were wedded to casteism. History is a great treat into the past. It let us live in an era where we are at present. It helps us to relate to people who influenced the shape of the present day. It enables us to understand how the world worked then and how it works now. It provides us with the frame work of knowledge that we need to build our entire lives. We can learn how things have changed ever since and they are the personalities that helped to change the scenario. -

1. RAJKOT the Struggle in Rajkot Has a Personal Touch About It for Me

1. RAJKOT The struggle in Rajkot has a personal touch about it for me. It was the place where I received all my education up to the matricul- ation examination and where my father was Dewan for many years. My wife feels so much about the sufferings of the people that though she is as old as I am and much less able than myself to brave such hardships as may be attendant upon jail life, she feels she must go to Rajkot. And before this is in print she might have gone there.1 But I want to take a detached view of the struggle. Sardar’s statement 2, reproduced elsewhere, is a legal document in the sense that it has not a superfluous word in it and contains nothing that cannot be supported by unimpeachable evidence most of which is based on written records which are attached to it as appendices. It furnishes evidence of a cold-blooded breach of a solemn covenant entered into between the Rajkot Ruler and his people.3 And the breach has been committed at the instance and bidding of the British Resident 4 who is directly linked with the Viceroy. To the covenant a British Dewan5 was party. His boast was that he represented British authority. He had expected to rule the Ruler. He was therefore no fool to fall into the Sardar’s trap. Therefore, the covenant was not an extortion from an imbecile ruler. The British Resident detested the Congress and the Sardar for the crime of saving the Thakore Saheb from bankruptcy and, probably, loss of his gadi. -

Ahimsa Center- K-12 Teacher Institute Lesson Plan Title of Lesson

Ahimsa Center- K-12 Teacher Institute Lesson Plan Title of Lesson: Ahimsa in the Real World: Truth, Love, and Nonviolence. Lesson By: Melissa Ardon Grade Level/ Subject Areas: Class Size: Time/ Duration of Lesson: Second Grade 20 3 days 45 minutes each day Objectives of Lesson: • Students will learn to define ahimsa as love, truth, and nonviolence. • Students will create an abstract painting to show their understanding of feelings of nonviolence by using “feeling colors.” • Students will write and describe their painting and how it represents nonviolence. Lesson Abstract: Students in second grade will learn about Gandhi’s philosophy of ahimsa. Through a digital story, honesty story, abstract art, and writing, students will learn about Gandhi’s philosophy of ahimsa. Lesson Content: Background on Mohandas K. Gandhi Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was born on October 2, 1869, in a small town of India, Porbandar. He was born to Karamchand and Putlibai Gandhi. His father served as prime minister of their town and his mother, Putlibai, was a devout illiterate hindu girl. Putlibai attended daily temple services and fasted frequently throughout the year. At the tender age of thirteen he married Kasturbai. By eighteen they were parents to a boy. They had four children. At nineteen Gandhi sailed to London to attend law school. Upon earning his law degree, he returned to India only to find no job opportunities and feeling like a failure. He was offered an attorney position in South Africa and it is where he first began to practice law. When Gandhi arrived to South Africa he had two very shocking incidents that changed his perspective. -

Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar

z:\ ambedkar\vol-09\vol9-01.indd MK SJ 10-1-2013/YS-13-11-2013 1 Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar (14th April 1891 - 6th December 1956) z:\ ambedkar\vol-09\vol9-01.indd MK SJ 10-1-2013/YS-13-11-2013 2 BLANK z:\ ambedkar\vol-09\vol9-01.indd MK SJ 10-1-2013/YS-13-11-2013 3 Governing Class and the Servile Class Nobody will have any quarrel with the abstract principle that nothing should be done whereby the best shall be superseded by one who is only better and the better by one who is merely good and the good by one who is bad……. But Man is not a mere machine. He is a human being with feelings of sympathy for some and antipathy for others. This is even true of the ‘best’ man. He too is charged with the feelings of class sympathies and class antipathies. Having regard to these considerations the ‘best’ man from the governing class may well turn out to be the worst from the point of view of the servile classes. The difference between the governing classes and the servile classes in the matter of their attitudes towards each other is the same as the attitude a person of one nation has for that of another nation. - Dr. Ambedkar in ‘What Congress.... etc.’ z:\ ambedkar\vol-09\vol9-01.indd MK SJ 10-1-2013/YS-13-11-2013 4 z:\ ambedkar\vol-09\vol9-01.indd MK SJ 10-1-2013/YS-13-11-2013 5 DR. -

Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, Volume 98

1. GIVE AND TAKE1 A Sindhi sufferer writes: At this critical time when thousands of our countrymen are leaving their ancestral homes and are pouring in from Sind, the Punjab and the N. W. F. P., I find that there is, in some sections of the Hindus, a provincial spirit. Those who are coming here suffered terribly and deserve all the warmth that the Hindus of the Indian Union can reasonably give. You have rightly called them dukhi,2 though they are commonly called sharanarthis. The problem is so great that no government can cope with it unless the people back the efforts with all their might. I am sorry to confess that some of the landlords have increased the rents of houses enormously and some are demanding pagri. May I request you to raise your voice against the provincial spirit and the pagri system specially at this time of terrible suffering? Though I sympathize with the writer, I cannot endorse his analysis. Nevertheless I am able to testify that there are rapacious landlords who are not ashamed to fatten themselves at the expense of the sufferers. But I know personally that there are others who, though they may not be able or willing to go as far as the writer or I may wish, do put themselves to inconvenience in order to lessen the suffering of the victims. The best way to lighten the burden is for the sufferers to learn how to profit by this unexpected blow. They should learn the art of humility which demands a rigorous self-searching rather than a search of others and consequent criticism, often harsh, oftener undeserved and only sometimes deserved. -

Vijay Pratap

COMPILATION OF ARTICLES WRITTEN BY VIJAY PRATAP COMPILATION OF ARTICLES WRITTEN BY VIJAY PRATAP ENGLISH Printed on 13 December 2017 1 Printed on 13 December 2017 COMPILATION OF ARTICLES WRITTEN BY VIJAY PRATAP CONTENT LIST ARTICLES Page No. 1. Elections in India and their Impact on Weaker Sections 1-7 2 Danger of the Emergence of Inferiority Complex Pessimism 8-10 too 3 Changing Contours of Dalit Politics 11-14 4 Bahujan Wants Active Participation 15-17 5 Independent Dalit role not feasible in Bihar 18-20 6 The Context of the State Assembly Elections: Some Reflections 21-25 7 Lest We Lose the War 26-29 8 Excerpts from a letter to a friend on the future of Vasudhaiva 30-34 Kutumbakam 9 A Forum of Dialogues on Global Responsibility Towards 35-39 Democracy 10 The ‘Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam’ Initiative 40-42 11 A Brief Note on “India - Central Asia Dialogue” 43-45 12 Notes on Voluntarism 46-48 13 Samvaad: A Personal of Journey of Discovering Dialogue as a 49-53 New Tool for Intervention 14 Victim, Perpetrator and Innocent Spectator: Introspecting 54-56 about Terrorism 15 Politics of Right to Information 57-60 2 Printed on 13 December 2017 COMPILATION OF ARTICLES WRITTEN BY VIJAY PRATAP 16 A Dialogue on Democracy 61-67 17 Poverty in India – An Overview 68-78 18 States and Democracy in South Asia 79-80 19 Ten Dialogues on "Policy Interventions for Consolidation of 81-82 Democracy" 20 Conversations on Democracy - Anil Bhattarai and Vijay 83-86 Pratap 21 Corruption and Communalism: Anti-Democratic Elements of 87-92 Indian Politics- Vijay Pratap 22 Towards North-South Solidarity : Some Challenges for 93-95 Building North-South Solidarity - Vijay Pratap 23 The Urgency of Dialogues on Democracy - Anil Bhattarai and 96-97 Vijay Pratap 24 Minorities and Democracy 98-99 25 Some Reflections on Funding and Voluntarism- Vijay Pratap; 100-103 Assisted by G. -

The Mountain Path Vol. 22 No. 4, Oct 1985

VOL. 22 No. IV OCTOBER 1985 THE MOUNTAIN PATH Editorial Board (A QUARTERLY) Sri K.K. Nambiar Mrs. Lucy Cornelssen "Arunachala! Thou dost root out the ego of those who meditate on Thee in the Smt. Shanta Rungachary heart. Oh Arunachala!" Dr. K. Subrahmaniam — The Marital Garland of Letters, verse 1 Sri A.R. Natarajan Vol. 22 OCTOBER 1985 No. 4 Publisher T.N. Venkataraman CONTENTS President, Board of Trustees, Page Sri Ramanasramam EDITORIAL: Ramana's Fate Tiruvannamalai — A.R. Natarajan ... 225 Two Decades of The Mountain Path . 228 Managing Editor Surrender V. Canesan — David Godman ... 231 A Guided Tour of Heaven II Letters and remittances should —• Douglas Harding . 235 be sent to : A Station Passed Through (Chapter II) The Managing Editor, — Arthur Osborne . 239 ''THE MOUNTAIN PATH", The Speciality of Ramana and His Teachings Sri Ramanasramam, P.O., — Prof. N.R. Krishnamoorthy Iyer . 241 Tiruvannamalai—606^603 S. India. Morality and Self Knowledge: in the light of the Life and the Teachings of Bhagavan Sri Ramana Annual Subscription — Michael lames . 242 How I Came to Bhagavan Sri Ramana INDIA Rs. 15 — Gobindram H. Daswani ... 250 FOREIGN £4.00 $8.00 Sri Bhagavan's Introduction to Vivekachudamani Life Subscription — Jr. by Sadhu Om and Michael lames . 252 Subramania Bharati: A God-Centred Poet Rs.150 £35.00 $70 — Dr. K. Subrahmanian . 259 Noble Ramana Single Copy — V. Ganesan . 261 Rs.4.00 £1.20 $2.50 Some Impressions of Sri Ramana Maharshi — Swami Ritajananda . 267 IA Precious Relic . 269 I'Turiya' — The Natural State Is it true Silence to rest — N.N. -

Tribals Under Siege

Nirmalangshu Mukherji is a careful, judicious scholar, and his T inquiry into these intricate issues is sensitive and persuasive. h NOAM CHOMSKY e M A must read for all those that follow the intense debates on politics and development in India. This book explores the writings of Maoist a ideologues relating to the Maoist movement in India’s tribal regions. o Mukherji develops a serious critique of Indian state policies and the is violent response to them, preferring the large social movements that t advocate an alternative path of development through non-violent s in resistance. ANURADHA M. CHENOY, Professor in the School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, co-author of Maoist And Other Armed I Conflicts (2010) n dia The Maoists in India delves deep into one of the most intractable but under-reported insurgencies in the developing world – the decades long battle between the Indian state and the Maoist groups who control significant parts of tribal India. Nirmalangshu Mukherji explains the devastating impact on India’s tribal Nirmalangs population of neoliberalism and armed aggression by the State, as well as the impact of the armed struggle by the Maoists. Unlike most accounts, Mukherji takes an unflinching look at each of the Maoists’ interventions and critically examines the programme proposed by their prominent intellectual sympathisers. The book examines the idea of armed struggle in the context of a well-established parliamentary democracy and focuses h The Maoists in India on the Maoists’ own political philosophy, looking critically at whether their u Muk strategy can help to deliver social justice and liberation for India’s poor. -

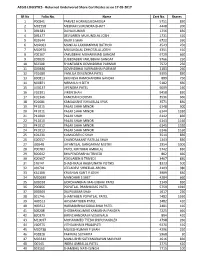

AEGIS LOGISTICS - Returned Undelivered Share Certificates As on 17-05-2017

AEGIS LOGISTICS - Returned Undelivered Share Certificates as on 17-05-2017 SR No Folio No. Name Cert No. Shares 1 P00841 PARVEZ HORMUSJI DAROGA 5751 830 2 M01558 MEENAXI SURENDRA BHATT 4448 200 3 D01681 DAYALKUMAR 1756 830 4 D01477 DEVILABEN MUKUNDLAL JOSHI 1731 410 5 R02644 RAJIV S SHAH 6722 260 6 M02063 MANILAL LAXMANBHAI RATHOD 4523 250 7 M00970 MUKUNDLAL CHHOTALAL JOSHI 4351 410 8 Y00107 YAKUBBHAI MUHAMMAD GANGAT 9729 660 9 Z00039 ZUBEDABEN YAKUBBHAI GANGAT 9766 250 10 S02308 SHANTABEN GOVINDBHAI PARMAR 7572 250 11 G00486 GOVINDBHAI VARWABHAI PARMAR 2183 260 12 V01680 VANLILA DEVENDRA PATEL 9395 830 13 B00813 BHUNESH RAMCHANDRA GANDHI 889 750 14 N00871 NIRMALA H SETH 5182 660 15 U00137 UPENDRA PATEL 9009 160 16 V02301 VIREN SHAH 9458 830 17 K01346 KANCHAN D DOSHI 3536 660 18 K01681 KAMALKANT ISHVARLAL VYAS 3571 830 19 P41015 PALAK SHAH MINOR 6148 900 20 P41011 PALAK SHAH MINOR 6144 1330 21 P41009 PALAK SHAH 6142 830 22 P41010 PALAK SHAH MINOR 6143 1160 23 P41012 PALAK SHAH MINOR 6145 1330 24 P41013 PALAK SHAH MINOR 6146 1160 25 K01230 KUMUDBEN C SHAH 3514 830 26 C00557 CHANDRAKANT RATILAL SHAH 1343 830 27 J00548 JAYANTILAL GANGARAM MISTRY 2954 1000 28 P00783 PATEL KIRITBHAI AMBALAL 5742 830 29 B00642 BHUPENDRABHAI TRIVEDI 862 660 30 K00967 KOKILABEN B TRIVEDI 3467 830 31 S10141 SHASHIKALA RAGHUNATH POTNIS 8323 500 32 L00702 LEELADEVI SHREELAL ARORA 4103 980 33 K61108 KRUSHAN KANT V JOSHI 3989 830 34 M00690 MANOHAR S SHET 4284 660 35 G00338 GORDHANBHAI MAHIJIBHAI PATEL 2149 830 36 P00866 POPATLAL PRABHUDAS PATEL 5759 1910 37 D00569