9789401474153.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The War and Fashion

F a s h i o n , S o c i e t y , a n d t h e First World War i ii Fashion, Society, and the First World War International Perspectives E d i t e d b y M a u d e B a s s - K r u e g e r , H a y l e y E d w a r d s - D u j a r d i n , a n d S o p h i e K u r k d j i a n iii BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA 29 Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2, Ireland BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2021 Selection, editorial matter, Introduction © Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian, 2021 Individual chapters © their Authors, 2021 Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identifi ed as Editors of this work. For legal purposes the Acknowledgments on p. xiii constitute an extension of this copyright page. Cover design by Adriana Brioso Cover image: Two women wearing a Poiret military coat, c.1915. Postcard from authors’ personal collection. This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Licence. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third- party websites referred to or in this book. -

Love and Loss Presseunterlage Engl

LENTOS Kunstmuseum Linz Information Sheet LOVE & LOSS Fashion and Mortality 13 March to 7 June 2015 -Nummer 0002852 DVR LENTOS Kunstmuseum Linz, A-4021 Linz, Ernst-Koref-Promenade 1 Tel: +43 (0)732.7070-3600 Fax: +43 (0)732.7070-3604 www.lentos.at Content Exhibition Facts ……………………………………………………………………………… 3 Exhibition Texts / Artits ...………………………………………………………………...….. 4 Exhibition Booklet Texts …………………………………………………………….…….... 5 Press Images ………………………………………………………………………….…....... 18 Seite 2 Exhibition Facts Exhibition Title LOVE & LOSS. Fashion and Mortality Exhibition Period 13 March to 7 June 2015 Opening Thursday, 12 March 2015, 7 pm Press Conference Thursday, 12 March 2015, 11 am Exhibition Venue LENTOS Kunstmuseum Linz, exhibition hall, first floor Curator Ursula Guttmann Exhibits About 160 works of art, under it High and Street Fashion, photographs, videos, sculptures, paintings, graphic works and installations by 52 artists and artist groups Catalogue The exhibition is accompanied by the publication LOVE & LOSS . Edited in Verlag für moderne Kunst. With texts by Ursula Guttmann, Thomas Macho, Stella Rollig and Barbara Vinken as well as two interviews with Cooper & Gorfer and between Nick Knight/SHOWstudio and Kristen McMenamy. 160 pages, price: € 22 Saaltexte A free exhibition booklet with information on the exhibits is available in German and English language. Supported by Contact Ernst-Koref-Promenade 1, 4020 Linz, Tel. +43(0)732/7070-3600; [email protected], www.lentos.at Opening Hours Tue–Sun 10am to 6pm, Thur 10am to 9pm, Mon closed Admission € 8, concessions € 6,50 Press Contact Nina Kirsch, Tel. +43(0)732/7070-3603, [email protected] Available at the Press Conference: Bernhard Baier, Deputy Mayor and Head of Municipal Department of Culture Stella Rollig, Director LENTOS Kunstmuseum Linz Ursula Guttmann, Curator Several artists are present. -

Total Work of Fashion: Bernhard Willhelm and the Contemporary Avant-Garde

TOTAL WORK OF FASHION: BERNHARD WILLHELM AND THE CONTEMPORARY AVANT-GARDE CHARLENE KAY LAU A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN ART HISTORY AND VISUAL CULTURE YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO April 2016 © Charlene Kay Lau, 2016 ii Abstract In fashion discourse, the term “avant-garde” is often applied to garments that fall outside of the mainstream fashion, whether experimental, conceptual or intellectual. However, such usage overlooks the social and political aims of the historical, artistic avant-gardes. Through an examination of the contemporary avant-garde fashion label Bernhard Willhelm – led by designers Bernhard Wilhelm and Jutta Kraus – this dissertation reconnects the historical or original vanguard and its revolutionary potential and proposes that Bernhard Willhelm belongs to an emerging, contemporary narrative of the avant- garde that intersects with fashion. In this study, I analyze Willhelm and Kraus’s collections, ephemera, runway presentations, exhibitions, online media, fashion films and critical reception from the brand’s inception in 1999 to 2016. Firstly, I develop the notion of “fashion-time” and contend that Willhelm and Kraus’s designs reject accelerated change, oscillating between the temporalities of fashion and anti-fashion and fashion and art. Secondly, I argue that the designers devise a political fashion, one that simultaneously critiques global politics and challenges norms in the fashion system. Thirdly, I assert that enduring collaboration with other cultural producers underpins Willhelm and Kraus’s work. The interdisciplinarity born of their collective work informs their spectacular visual language, the of sum of which I term a “total work of fashion.” By exploring these tenets of Willhelm and Kraus’s practice, I demonstrate that the avant- garde project is dynamic and in constant flux, at times incorporating dialectical facets that continually expand the disciplines of fashion and art. -

Fashion Department 12 13 14 JUNE Waagnatie Hangar 29 Rijnkaai 150 Doors 7Pm Tickets Seats € 35 Standing € 12 T+32 3 338 95 85

Fashion Department 12 13 14 JUNE Waagnatie hangar 29 rijnkaai 150 Doors 7pm tickets seats € 35 stanDing € 12 t+32 3 338 95 85 WWW.antWerp-Fashion.be OUTFIT — CLARA JUNGMAN MALMQUIST PHOTOGRAPHY — RONALD STOOPS MAKE-UP — INGE GROGNARD STYLING — DIRK VAN SAENE MODEL — KIM PEERS GRAPHIC DESIGN — PAUL BOUDENS PHOTOGRAPHIC ASSISTANCE — PRISCILLA GILS SHOW 2014 Poster.indd 1 05/05/14 07:44 SHOW2014 On June 12th, 13th&15th, the Fashion Department of the Artesis Plantijn University College Antwerp presents its annual fashion show at Hangar 29 in Antwerp. The graduation show of the Antwerp Fashion Department is a celebration of fashion, bringing together some 6.000 spectators from all over the world, not only to judge and/or admire the collections of our students, but also for the unique atmosphere of this grand defile. Once a year, the building is filled with friends, fashion enthusiasts, manufacturers, former students, fashion designers, styling agencies, culture buffs and the press. The show is repeated three evenings in a row. Students from all four years show their work on the catwalk. An international jury of experts in fashion and creativity judges their collections and installations. “The Royal Academy of Fine Arts and its Fashion Department are internationally renowned and enjoy a wide esteem for their excellence. Talented young people from all over the world find their way to fashion city Antwerp to be educated and to develop their creativity, under the inspiring supervision of Walter Van Beirendonck and his team. Three days long, students show their creative designs in a wonderful show.”, Pascale De Groote, vice-chancellor Artesis Plantijn University College. -

Belgium at a Glance

Belgium at a glance Belgium – a bird's eye view Belgium, a country of regions ................................................................ 5 A constitutional and hereditary monarchy .............................................6 A country full of creative talent ............................................................. 7 A dynamic economy ...............................................................................8 Treasure trove of contrasts ...................................................................8 Amazing history! ....................................................................................9 The advent of the state reform and two World Wars ........................... 10 Six state reforms ...................................................................................11 Working in Belgium An open economy .................................................................................13 Flexibility, quality and innovation ..........................................................13 A key logistics country ......................................................................... 14 Scientific research and education .........................................................15 Belgium – a way of life A gourmet experience ...........................................................................17 Fashion, too, is a Belgian tradition ...................................................... 18 Leading-edge design ............................................................................ 19 Folklore and traditions -

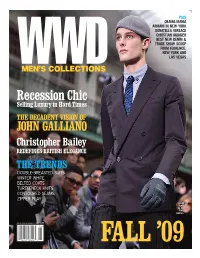

Recession Chic

PLUS OBAMA-MANIA ARMANI IN NEW YORK DONATELLA VERSACE CHRISTIAN AUDIGIER BEST NEW DENIM & TRADE SHOW SCOOP FROM FLORENCE, NEW YORK AND WWD LAS VEGAS MEN’S COLLECTIONS Recession Chic Selling Luxury in Hard Times THE DECADENT VISION OF JOHN GALLIANO Christopher Bailey REDEFINES BRITISH ELEGANCE THE TRENDS DOUBLE-BREASTED SUITS WINTER WHITE BELTED COATS TURTLENECK KNITS CONTOURED SEAMS ZIPPER PLAY Lanvin lights up the Paris runways. DISPLAY UNTIL SEPTEMBER 15, 2009 $6.00 FALL ’09 0316.MENSMAG.001.Cover;13.indd 1 3/10/09 1:57:10 PM NEW YORK | LONDON | TOKYO | SWISSARMY.COM NEW YORK | LONDON | TOKYO | SWISSARMY.COM DIRECTION retro sunglasses and pops of color MONTBLANC GUCCI 1.800.365.7989 NEIMANMARCUS.COM Backstage at DSquared. ON THE COVER A look from Lanvin photographed by For full collections Stephane Feugere. coverage, go to WWD.com 13 REDEFINING LUXE 42 CHECK MATE 56 NEW BLUE Designers rethink their values during men’s Burberry designer Christopher Bailey refl ects on the Seven key denim trends for fall ’09. fashion weeks in Milan, Paris and New York. art of disheveled elegance. By David Lipke By Jean Scheidnes By Jean Scheidnes 58 WALE WATCH 18 DEFINING MOMENTS 44 A DELICATE BALANCE Corduroy and astrakhan stand out as key From Armani’s newest fl agship to Levi’s oldest Alber Elbaz and Lucas Ossendrijver, the duo behind materials for fall. jeans, highlights from the runways and trade shows. Lanvin, break though in the City of Light. By Suzanne Blecher By Emilie Marsh 27 TRENDS 59 JUST SUIT ME Double-breasted suits come on strong, as do 45 THE VERSACE MAN European designers and men’s wear brands turtlenecks, rounded shoulders, belted coats and Donatella and men’s wear designer Alexandre renew their emphasis on tailored clothing. -

A.F.Vandevorst Ende Neu

UITGEVERIJ HANNIBAL WWW.hannIbalPublISHING.COM ‘A fascinating insight into the stimulating universe of Belgium’s cult fashion designer duo A.F.Vandevorst.’ A.F.Vandevorst Ende Neu A universe of fetishes, fur, leather, sensual folds and tight straitjackets… That is what Belgian fashion designers A.F. Vandevorst stand for. This publication celebrates the duo’s twentieth anniversary. An Vandevorst and Filip Arickx met in 1987, on their first day of school at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp. Ten years later, they set up their company Blixa and presented their first collection as A.F.Vandevorst in Paris. They have collaborated with such people as the flamboyant and world-famous hat designer Stephen Jones and have grown to become one of Belgium’s most edgy cult designers, closely connected to the Antwerp Six (Dries Van Noten, Ann Demeulemeester, Walter Van Beirendonck…). A.F.Vandevorst’s aesthetics are the result of their deep love for the visual arts, music and literature and their great interest in cultural archetypes. This book focuses on their diverse inspirations, including Joseph Beuys, the military and the medical world, and on other artists to whom An and Filip feel strong connections. Among the latter is Blixa Bargeld (Einstürzende Neubauten), who was the source of their first company’s name and has been a major inspiration ever since. This book provides an intimate, thrilling and stimulating insight into the fascinating world of A.F.Vandevorst. Be inspired by twenty years of limitless passion for fashion. With an introduction by Alix Browne and contributions by, among others, Dries Van Noten, Dirk Braeckman, Tim Blanks, Blixa Bargeld, Hannelore Knuts, Sally Singer, Linda Loppa and Suzy Menkes. -

Avant-Garde Fashion for the Masses

AVANT-GARDE FASHION FOR THE MASSES a study of consumer perception of avant-gardist designer brands after collaborating with mainstream fashion Image1; (Rick Owens, 2013) STOCKHOLM SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS Authors: Andrea Boodh, 21746 & Caroline Foerster, 40479 Supervisor: Hans Kjellberg Opponents: Joel Florén & Hanna Poutanen Examiner: Susanne Sweet Presentation: Stockholm, May 26, 2014 AVANT-GARDE FASHION FOR THE MASSES Boodh & Foerster, 2014 ABSTRACT The use of intra-industrial co-branding within fashion has increased dramatically over the last decades, with a wide range of partner combinations including even avant-garde fashion designers. These brands are often licensing collaborations with mainstream mass-market brands, but with uncertain effects for their brands. This study explores potential effects brand collaborations between high-end avant-garde fashion designers and low-end mass-market fashion brands have on consumer perception of the former. The applied research model combines general co-branding theory with theories on fashion in order to get an industry specific understanding of the consequences and effects of the brand collaborations. The study examines effects on consumer perception based on qualitative interviews with consumers and experts. The findings, in line with co-branding theory, show that the level of fit between the partnering brands in a collaboration influences the consumer perception of the avant-garde designer, where a higher degree of fit results in more positive attitudes. The avant-garde brand’s identity is shown to alter after a collaboration due to negative spillover effects from the mainstream ally. Further, the findings show the extended spread of the collaboration to have unanimous effects on the avant-garde brand and consumer perception. -

10 Good Reasons to Invest in Flanders Allow Us to Give You to 10 Different Reasons Why Flanders Is Europe’S Ultimate Location for Your Business Activities

10 good reasons to invest in Flanders Allow us to give you to 10 different reasons why Flanders is Europe’s ultimate location for your business activities. 10 crucial arguments which are the base of all sound investment decisions. You will be surprised to see the wide range of advantages our region has to offer you ... 1 Central location at the heart of Europe 2 Outstanding transport infrastructure 3 Globally recognized human capital 4 Diverse offering of tax benefits and fiscal incentives 5 Sustainable growth for major industries 6 State-of-the-art research centers 7 High density of knowledge clusters 8 Excellent results in international surveys 9 High quality of life for expat employees 10 Professional support in setting up your operations Central location at the heart of Europe 10 good reasons to invest in Flanders - An introduction to Europe’s ultimate business location Flanders is a prime business region. It is strategically located right in the center of the most prosperous part of Europe. In addition, its capital Brussels is home to the European decision-making centers. Two crucial factors for your company when making an investment decision in Europe. Close proximity to the European institutions At the heart of European Brussels is home to the Distances from Brussels purchasing power NATO headquarters and to (by road): Over 60 % of the European that of the European Union. • Amsterdam: 210 km purchasing power is situated No wonder that a large • Berlin: 780 km within a tight radius of 500 number of international • Dublin: 940 km kilometers around Flanders. governmental and non- • Düsseldorf: 270 km This means customers can governmental organizations • Copenhagen: 920 km be reached and served in the as well as corporate repre- • Lisbon: 2,100 km fastest of times. -

Fashion District in the Creative City Antwerp and Its Fashion Hub

Corso di Laurea magistrale (ordinamento ex D.M. 270/2004) in Economia e Gestione delle Arti e delle Attività Culturali Fashion district in the creative city Antwerp and its Fashion Hub Relatore Ch. Prof. Fabrizio Panozzo Laureando Laura Pappacoda Matricola 839935 Anno Accademico 2012 / 2013 1 “Fashion Districts in the Creative City. Antwerp and its Fashion Hub” Index Introduction 1.Creative Industries and the Creative Ecosystem 1.1 Definition of Creative Industries 1.1.2.The United Nation Perspective 1.2. Creative Industries in Europe 1.3. Policies / Creative Strategies 1.4. Creative Industries in cities spatial development. The Concept of Cluster. 1.5. Creative Class 1.5.1 Critique to the Creative Class Model 1.6. Fashion and Design as Creative Industries 1.6.1.Fashion as national identity 2. Antwerp Fashion. History and development of the Cluster. 2.1.1.First Phase: reconstruction of the sector. 2.1.2. Second half of 80’s. The rise of Belgian Avant-garde 2.2. Second Period: The Process of Antwerp as a Fashion Capital 2.3. Third Period: the identification of the fashion District 3. Antwerp Fashion District. 3.1.Introduction to the city of Antwerp 3.1.2. Maritime 3.1.3.Diamonds 3.1.4.Rubens 3.2.Fashion 3.3.ModeNatie 3.3.1.History of ModeNatie building 3.3.2.MOMU- Fashion Museum 3.3.2.1.Historical Collection 2 3.3.2.2.Textile Museum Vrieselhof 3.3.2.3.The lace collection 3.3.2.5. Contemporary Collection 3.3.2.6. The virtual museum and Europeana Fashion. -

Fashion Dept. on Top Floor

GRANTEE REPORT BY: MITRA RAJABI DEPARTMENT: FASHION DESIGN DATES OF ACTIVITY: 5/31/12 - 6/08/12 The Royal Academy’s Fashion Department in Antwerp, Belgium, is one of the most prestigious design schools in the world. It’s been the breeding ground of ‘The Antwerp Six’, a title given to a group of top fashion designers who influenced the fashion world, starting in the 1980’s, with their avantgarde collections: Ann Demeulemeester, Walter Van Beirendonck, Dirk Van Saene, Dries Van Noten, Dirk Bikkembergs and Marina Yee. The Academy has produced famous continuators such as Haider Ackerman, Raf Simons, Veronique Branquinho, and Martin Margiela. In fall 2011, I was the privileged recipient of an Otis Faculty Development Grant in support of attending The Royal Academy of Fine Arts’ Annual Fashion Show, in Antwerp. The Grant was given in an effort to study the school’s educational system and the current student work showcased in their annual Fashion Show, on June 7th, 2012. The Royal Academy will be celebrating its 50th Birthday in 2013. 1. The Challenge The Royal Academy’s Fashion Department is located on the 5th floor of MOMU, the Mode Museum (Fashion Museum), on the trendy Nationalestraat in the trendy fashion district of Antwerp. During my trip, the entire fashion department was in full preparation mode for the upcoming annual Show 2012. My request for a tour of the campus was unfortunately, but understandably, denied. Thus, my closest encounter with the school was the outside door. The interior of the MOMU; the Fashion Department of The Royal Academy is located on the top floor, accessible only via private elevator. -

Together Magazine and Art – We Miss Her Very Much

WHERE NEWS & BUSINESS MEET GLAMOUR & GOOD TIMES #10 /OCTOBER 2008 TogetherRECOMMENDS magazine INTERVIEWS POINT EUROPEAN REAL George Lucas OF VIEW VICE ESTATE Alain Courtois Street Smokeless Housing Martin Solveig protests tobacco explosion ge CLUB MED HOLIDAYS, WHERE HAPPINESS, r a h c RELAXATION AND REFINEMENT ARE EVERYTHING a r xt E * UNIQUE LOCATIONS TO EXPERIENCE THE MOST UNFORGETTABLE MOMENTS 64 SUMMER VILLAGES AROUND THE WORLD MALDIVES, MAURITIUS, BRAZIL, INDONESIA, ... RENOVATED VILLAGES WELL-KNOWN ARCHITECTS AND DESIGNERS SPACE AND COMFORT* DELUXE ROOMS OR SUITES WITH SEA VIEW WELL-BEING AND RELAXATION PRESTIGIOUS SPA* PARTNERSHIPS SPA* NUXE SPA* CINQ MONDES AN ATMOSPHERE BOTH WARM AND REFINED clubmed.be ALL INCLUSIVE HAPPINESS WHERE HAPPINESS MEANS THE WORLD Together_230x340.indd 1 16/07/08 12:03:07 EDITORIAL Be it ever www.saab-ids.be so humble… To have Together delivered free, subscribe at www.together-magazine.eu We work mainly with there’s no place national and international advertisers. If you are interested in our rates, please contact. Bertrand de Moffarts : like Belgium ! [email protected] or T. +32 (0)475 41 63 62 I have a growing suspicion, chose to live here, you’ll have your answers Nothing in this magazine at the ready ! And that’s not all – our may be reproduced in and I believe that I’m not whole or in part without alone. Allow me to explain. fashion specialists, with their take on the written permission the end-of-studies work at La Cambre of the publisher. I have travelled the world, Double Turbo The publisher cannot be held and the Antwerp Academy, highlight responsible for the views visited many impressive and opinions expressed in how young Belgian designers are looking this magazine by authors megalopolises and also to make it big on the international and contributors.