Avant-Garde Fashion for the Masses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nietzsche and Aestheticism

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 1992 Nietzsche and Aestheticism Brian Leiter Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Brian Leiter, "Nietzsche and Aestheticism," 30 Journal of the History of Philosophy 275 (1992). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Notes and Discussions Nietzsche and Aestheticism 1o Alexander Nehamas's Nietzsche: L~fe as Literature' has enjoyed an enthusiastic reception since its publication in 1985 . Reviewed in a wide array of scholarly journals and even in the popular press, the book has won praise nearly everywhere and has already earned for Nehamas--at least in the intellectual community at large--the reputation as the preeminent American Nietzsche scholar. At least two features of the book may help explain this phenomenon. First, Nehamas's Nietzsche is an imaginative synthesis of several important currents in recent Nietzsche commentary, reflecting the influence of writers like Jacques Der- rida, Sarah Kofman, Paul De Man, and Richard Rorty. These authors figure, often by name, throughout Nehamas's book; and it is perhaps Nehamas's most important achievement to have offered a reading of Nietzsche that incorporates the insights of these writers while surpassing them all in the philosophical ingenuity with which this style of interpreting Nietzsche is developed. The high profile that many of these thinkers now enjoy on the intellectual landscape accounts in part for the reception accorded the "Nietzsche" they so deeply influenced. -

The Rhetoric of Cool: Computers, Cultural Studies, and Composition

THE RHETORIC OF COOL: COMPUTERS, CULTURAL STUDIES, AND COMPOSITION By JEFFREY RICE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS Eage ABSTRACT iv 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1963 12 Baudrillard 19 Cultural Studies 33 Technology 44 McLuhan’s Cool Media as Computer Text 50 Cyberculture 53 Writing 57 2 LITERATURE 61 Birmingham and Baraka 67 The Role of Literature 69 The Beats 71 Burroughs 80 Practicing a Burroughs Cultural Jamming 91 Eating Texts 96 Kerouac and Nostalgia 100 History VS Nostalgia 104 Noir 109 Noir Means Black 115 The Signifyin(g) Detective 124 3 FILM AND MUSIC 129 The Apparatus 135 The Absence of Narrative 139 Hollywood VS The Underground 143 Flaming Creatures 147 The Deviant Grammar 151 Hollywood VS The Underground 143 Scorpio Rising 154 Music: Blue Note Records 163 Hip Hop - Samplin’ and Skratchin’ 170 The Breaks 174 ii 1 Be the Machine 178 Musical Production 181 The Return of Nostalgia 187 4 COMPOSITION 195 Composition Studies 200 Creating a Composition Theory 208 Research 217 Writing With(out) a Purpose 221 The Intellectual Institution 229 Challenging the Institution 233 Technology and the Institution 238 Cool: Computing as Writing 243 Cool Syntax 248 The Writer as Hypertext 25 Conclusion: Living in Cooltown 255 5 REFERENCES 258 6 BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH ...280 iii Abstract of Dissertation Presented to the Graduate School of the University of Florida in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy THE RHETORIC OF COOL: COMPUTERS, CULTURAL STUDIES, AND COMPOSITION By Jeffrey Rice December 2002 Chairman: Gregory Ulmer Major Department: English This dissertation addresses English studies’ concerns regarding the integration of technology into the teaching of writing. -

Mike Kelley's Studio

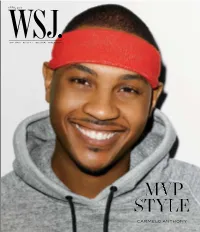

No PMS Flood Varnish Spine: 3/16” (.1875”) 0413_WSJ_Cover_02.indd 1 2/4/13 1:31 PM Reine de Naples Collection in every woman is a queen BREGUET BOUTIQUES – NEW YORK FIFTH AVENUE 646 692-6469 – NEW YORK MADISON AVENUE 212 288-4014 BEVERLY HILLS 310 860-9911 – BAL HARBOUR 305 866-1061 – LAS VEGAS 702 733-7435 – TOLL FREE 877-891-1272 – WWW.BREGUET.COM QUEEN1-WSJ_501x292.indd 1-2 01.02.13 16:56 BREGUET_205640303.indd 2 2/1/13 1:05 PM BREGUET_205640303.indd 3 2/1/13 1:06 PM a sporting life! 1-800-441-4488 Hermes.com 03_501,6x292,1_WSJMag_Avril_US.indd 1 04/02/13 16:00 FOR PRIVATE APPOINTMENTS AND MADE TO MEASURE INQUIRIES: 888.475.7674 R ALPHLAUREN.COM NEW YORK BEVERLY HILLS DALLAS CHICAGO PALM BEACH BAL HARBOUR WASHINGTON, DC BOSTON 1.855.44.ZEGNA | Shop at zegna.com Passion for Details Available at Macy’s and macys.com the new intense fragrance visit Armanibeauty.com SHIONS INC. Phone +1 212 940 0600 FA BOSS 0510/S HUGO BOSS shop online hugoboss.com www.omegawatches.com We imagined an 18K red gold diving scale so perfectly bonded with a ceramic watch bezel that it would be absolutely smooth to the touch. And then we created it. The result is as aesthetically pleasing as it is innovative. You would expect nothing less from OMEGA. Discover more about Ceragold technology on www.omegawatches.com/ceragold New York · London · Paris · Zurich · Geneva · Munich · Rome · Moscow · Beijing · Shanghai · Hong Kong · Tokyo · Singapore 26 Editor’s LEttEr 28 MasthEad 30 Contributors 32 on thE CovEr slam dunk Fashion is another way Carmelo Anthony is scoring this season. -

An Aesthetic of the Cool: West Africa

An Aesthetic of the Cool Author(s): Robert Farris Thompson Source: African Arts, Vol. 7, No. 1 (Autumn, 1973), pp. 40-43+64-67+89-91 Published by: UCLA James S. Coleman African Studies Center Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3334749 . Accessed: 19/10/2014 02:46 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. UCLA James S. Coleman African Studies Center and Regents of the University of California are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to African Arts. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 142.104.240.194 on Sun, 19 Oct 2014 02:46:11 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions An Aesthetic of the Cool ROBERTFARRIS THOMPSON T he aim of this study is to deepen the understandingof a of elements serious and pleasurable, of responsibility and of basic West African/Afro-American metaphor of moral play. aesthetic accomplishment, the concept cool. The primary Manifest within this philosophy of the cool is the belief metaphorical extension of this term in most of these cultures that the purer, the cooler a person becomes, the more ances- seems to be control,having the value of composurein the indi- tral he becomes. -

Mathematics K Through 6

Building fun and creativity into standards-based learning Mathematics K through 6 Ron De Long, M.Ed. Janet B. McCracken, M.Ed. Elizabeth Willett, M.Ed. © 2007 Crayola, LLC Easton, PA 18044-0431 Acknowledgements Table of Contents This guide and the entire Crayola® Dream-Makers® series would not be possible without the expertise and tireless efforts Crayola Dream-Makers: Catalyst for Creativity! ....... 4 of Ron De Long, Jan McCracken, and Elizabeth Willett. Your passion for children, the arts, and creativity are inspiring. Thank you. Special thanks also to Alison Panik for her content-area expertise, writing, research, and curriculum develop- Lessons ment of this guide. Garden of Colorful Counting ....................................... 6 Set representation Crayola also gratefully acknowledges the teachers and students who tested the lessons in this guide: In the Face of Symmetry .............................................. 10 Analysis of symmetry Barbi Bailey-Smith, Little River Elementary School, Durham, NC Gee’s-o-metric Wisdom ................................................ 14 Geometric modeling Rob Bartoch, Sandy Plains Elementary School, Baltimore, MD Patterns of Love Beads ................................................. 18 Algebraic patterns Susan Bivona, Mount Prospect Elementary School, Basking Ridge, NJ A Bountiful Table—Fair-Share Fractions ...................... 22 Fractions Jennifer Braun, Oak Street Elementary School, Basking Ridge, NJ Barbara Calvo, Ocean Township Elementary School, Oakhurst, NJ Whimsical Charting and -

MF-Romanticism .Pdf

Europe and America, 1800 to 1870 1 Napoleonic Europe 1800-1815 2 3 Goals • Discuss Romanticism as an artistic style. Name some of its frequently occurring subject matter as well as its stylistic qualities. • Compare and contrast Neoclassicism and Romanticism. • Examine reasons for the broad range of subject matter, from portraits and landscape to mythology and history. • Discuss initial reaction by artists and the public to the new art medium known as photography 4 30.1 From Neoclassicism to Romanticism • Understand the philosophical and stylistic differences between Neoclassicism and Romanticism. • Examine the growing interest in the exotic, the erotic, the landscape, and fictional narrative as subject matter. • Understand the mixture of classical form and Romantic themes, and the debates about the nature of art in the 19th century. • Identify artists and architects of the period and their works. 5 Neoclassicism in Napoleonic France • Understand reasons why Neoclassicism remained the preferred style during the Napoleonic period • Recall Neoclassical artists of the Napoleonic period and how they served the Empire 6 Figure 30-2 JACQUES-LOUIS DAVID, Coronation of Napoleon, 1805–1808. Oil on canvas, 20’ 4 1/2” x 32’ 1 3/4”. Louvre, Paris. 7 Figure 29-23 JACQUES-LOUIS DAVID, Oath of the Horatii, 1784. Oil on canvas, approx. 10’ 10” x 13’ 11”. Louvre, Paris. 8 Figure 30-3 PIERRE VIGNON, La Madeleine, Paris, France, 1807–1842. 9 Figure 30-4 ANTONIO CANOVA, Pauline Borghese as Venus, 1808. Marble, 6’ 7” long. Galleria Borghese, Rome. 10 Foreshadowing Romanticism • Notice how David’s students retained Neoclassical features in their paintings • Realize that some of David’s students began to include subject matter and stylistic features that foreshadowed Romanticism 11 Figure 30-5 ANTOINE-JEAN GROS, Napoleon at the Pesthouse at Jaffa, 1804. -

Brands We Love

Brands We Love # D I N T DENIM 3.1 PHILLIP LIM DANSKO IRO NICOLE MILLER THEORY AG 360 CASHMERE DAVID YURMAN ISABEL MARANT NILI LOTAN THE GREAT AGOLDE We Do Not Accept: DEREK LAM ISSEY MIYAKE NO 6 STORE THE ROW AMO DL1961 NORTH FACE TIBI CITIZENS OF HUMANITY ABERCROMBIE & FITCH H&M A DOLCE & GABBANA TIFFANY & CO CURRENT/ELLIOTT AMERICAN APPAREL HOLLISTER ACNE STUDIOS AMERICAN EAGLE HOT TOPIC DONNA KARAN J TOCCA DL1961 ANN TAYLOR AG INC DOSA J BRAND O TOD’S FRAME ANGIE JACLYN SMITH AGL DRIES VAN NOTEN J CREW OBAKKI TOM FORD GOLDSIGN APT 9 JOE BOXER AGOLDE DVF JAMES PERSE OFFICINE CREATIVE TOP SHOP HUDSON ATTENTION JUICY COUTURE ALAIA JEAN PAUL GAULTIER OPENING CEREMONY AX PARIS LAND’S END TORY BURCH J BRAND BANANA REPUBLIC ALC OSCAR DE LA RENTA LOVE 21 JIL SANDER TRINA TURK JOES BDG LUX ALEXANDER MCQUEEN E JIMMY CHOO LEVIS BEBE MAX STUDIO ALEXANDER WANG EILEEN FISHER JOIE MOTHER BLUES METAPHOR BONGO ALICE & OLIVIA EMANUEL UNGARO P U MOUSSY MISS ME PAIGE CANDIE’S MISS TINA ANNA SUI ELIZABETH & JAMES UGG PAIGE CANYON RIVER PARKER MOSSIMO ANN DEMEULEMEESTER EMILIO PUCCI K ULLA JOHNSON R13 CATALINA NICKI MINAJ ANTHROPOLOGIE BRANDS ENZA COSTA KATE SPADE PATAGONIA RE/DONE CATHY DANIELS OLD NAVY ATM ERDEM PIERRE HARDY CHAPS ROCK & REPUBLIC SIMON MILLER CHARLOTTE RUSSE AUTUMN CASHMERE EVERLANE PRADA ROUTE 66 V CHIC ROXY AVANT TOI L PROENZA SCHOULER VALENTINO CHICOS L’AGENCE SAG HARBOR VANESSA BRUNO ATHLETIC CHRISTINALOVE SIMPLY VERA WANG F LANVIN VELVET ALO COVINGTON SO... CROFT & BARROW FENDI LEM LEM R VERONICA BEARD ATHLETA SONOMA LEVIS RACHEL COMEY DAISY FUENTES SOFIA VERGARA B FIORENTINI + BAKER VERSACE LULULEMON DANSKIN LOEFFLER RANDALL RAG & BONE STUDIO TAHARI BABATON FREE PEOPLE VICTORIA BECKHAM OUTDOOR VOICES ECOTE TARGET BALENCIAGA FRYE LOEWE RAILS VINCE NORTH FACE ELLE URBAN OUTFITTERS ETC.. -

The Sixties Counterculture and Public Space, 1964--1967

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 2003 "Everybody get together": The sixties counterculture and public space, 1964--1967 Jill Katherine Silos University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Silos, Jill Katherine, ""Everybody get together": The sixties counterculture and public space, 1964--1967" (2003). Doctoral Dissertations. 170. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/170 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Modernism Triumphant – Commercial and Institutional Buildings

REVISED FEB 2010 Louisiana Architecture 1945 - 1965 Modernism Triumphant – Commercial and Institutional Buildings Jonathan and Donna Fricker Fricker Historic Preservation Services, LLC September 2009 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND America in the years following World War II saw the triumph of European Modernism in commercial and institutional buildings. Modernism was a style that claimed not to be a style, but rather an erudite and compelling movement towards rationality and purposefulness in architecture. It grew out of art, architectural and handicraft reform efforts in Europe in the years after World War I. These came together in the Bauhaus school of design in Weimar, Germany, which sought to teach all artists, artisans and architects to work together, in common service, towards “the building of the future.” Originally founded in 1906 by the Grand-Duke of Saxe-Weimar as a school for the arts and crafts, the Bauhaus emerged in the 1920s as the focus of a radical new approach to industrial design and architecture. Inherent in the Bauhaus was a commitment to marshalling the greater art world in the service of humanity. And there were strong associations with political reform, socialism, and a mandate for art to respond to the machine age. The new architecture the Bauhaus school epitomized, the International Style as it came to be known, had a “stark cubic simplicity” (Nikolas Pevsner) – completely and profoundly devoid of ornament. Its buildings are characterized by: 1) a machined metal and glass framework, with flat neutral (generally white) surfaces pierced by thin bands of windows (ribbon windows) sometimes turning the corner; 2) an overall horizontal feel; 3) functional and decidedly flat roofs; 4) frequent use of the cantilever principal for balconies and upper stories; and 5) the use of “pilotis”—or slender poles – to raise the building mass, making it appear to float above the landscape. -

Blackface and Newfoundland Mummering Kelly Best

Document generated on 09/30/2021 1:10 p.m. Ethnologies “Making Cool Things Hot Again” Blackface and Newfoundland Mummering Kelly Best Hommage à Peter Narváez Article abstract In Honour of Peter Narváez This article critically examines instances of blackface in Newfoundland Volume 30, Number 2, 2008 Christmas mummering. Following Peter Narváez’s call for analysis of expressive culture from folklore and cultural studies approaches, I explore the URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/019953ar similarities between these two cultural phenomena. I see them as attempts to DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/019953ar work out racial and class tensions among the underclasses dwelling in burgeoning seaport towns along the North American seaboard that were intimately connected, at that time, through heavily-trafficked shipping routes. I See table of contents offer a reanalysis of the tradition that goes beyond unconscious, symbolic ritualism to one that examines mummering in a historical context. As such, I present evidence which troubles widely held understandings of Christmas Publisher(s) mummering as an English-derived calendar custom. Association Canadienne d'Ethnologie et de Folklore ISSN 1481-5974 (print) 1708-0401 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Best, K. (2008). “Making Cool Things Hot Again”: Blackface and Newfoundland Mummering. Ethnologies, 30(2), 215–248. https://doi.org/10.7202/019953ar Tous droits réservés © Ethnologies, Université Laval, 2008 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. -

The War and Fashion

F a s h i o n , S o c i e t y , a n d t h e First World War i ii Fashion, Society, and the First World War International Perspectives E d i t e d b y M a u d e B a s s - K r u e g e r , H a y l e y E d w a r d s - D u j a r d i n , a n d S o p h i e K u r k d j i a n iii BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA 29 Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2, Ireland BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2021 Selection, editorial matter, Introduction © Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian, 2021 Individual chapters © their Authors, 2021 Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identifi ed as Editors of this work. For legal purposes the Acknowledgments on p. xiii constitute an extension of this copyright page. Cover design by Adriana Brioso Cover image: Two women wearing a Poiret military coat, c.1915. Postcard from authors’ personal collection. This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Licence. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third- party websites referred to or in this book. -

Council of Fashion Designers of America

Council of Fashion Designers of America ANNUAL REPORT 2017 The mission of the Council of Fashion Designers of America is to strengthen the impact of American fashion in the global economy. B 1 Letter from the Chairwoman, Diane von Furstenberg, and the President and Chief Executive Officer, Steven Kolb In fashion, we respond to the world we live in, a point that was powerfully driven home in 2017. We were excited to see talents with broad cultural backgrounds and political ideas begin to express their experiences and beliefs through their collections. Diversity moved into the spotlight in ways we have never seen before. Designers embraced new approaches to business, from varying show formats to disruptive delivery cycles. It was also the year to make your voices heard, and CFDA listened. We engaged in civic initiatives important to our industry and partnered with Planned Parenthood, the ACLU, and FWD.us. We also relaunched our CFDA Health Initiative with guidelines to help those impacted by sexual assault or other forms of abuse. There’s no going back. In 2018, CFDA is moving ahead at full speed with an increased focus on inclusivity and women in fashion, the latter through an exciting new study with Glamour magazine. We may be a reflection of the world we live in, but we also work hard to make that world a better place. Altruism, after all, never goes out of style. 3 CFDA STRENGTHENED PILLARS WITH MISSION-DRIVEN ACTIONS MEMBERSHIP Fashion Professional Fashion Civic+ Retail Partnership Week + Market Development Supply Chain Philanthropy Opportunities SUSTAINABILITY INDUSTRY ENGAGEMENT SOCIAL AND EDITORIAL MARKETING AND EVENTS KEY UNCHANGED MODIFIED NEW PROVIDED INITIATIVES RELEVANT TO DESIGNERS EMERITUS AT EVERY STAGE OF CAREER DESIGNERS • Board Engagement • Philanthropy and Civic ICONIC Responsibility DESIGNERS • Mentorship • Editorial Visibility • Board Engagement • Fashion Week • Philanthropy and Civic ESTABLISHED Responsibility DESIGNERS • Mentorship • Editorial Visibility • NETWORK.