The Jedi of Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography for the Study of Shakespeare on Film in Asia and Hollywood

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 6 (2004) Issue 1 Article 13 Bibliography for the Study of Shakespeare on Film in Asia and Hollywood Lucian Ghita Purdue University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, and the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Ghita, Lucian. "Bibliography for the Study of Shakespeare on Film in Asia and Hollywood." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 6.1 (2004): <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.1216> The above text, published by Purdue University Press ©Purdue University, has been downloaded 2531 times as of 11/ 07/19. -

East-West Film Journal, Volume 3, No. 2

EAST-WEST FILM JOURNAL VOLUME 3 . NUMBER 2 Kurosawa's Ran: Reception and Interpretation I ANN THOMPSON Kagemusha and the Chushingura Motif JOSEPH S. CHANG Inspiring Images: The Influence of the Japanese Cinema on the Writings of Kazuo Ishiguro 39 GREGORY MASON Video Mom: Reflections on a Cultural Obsession 53 MARGARET MORSE Questions of Female Subjectivity, Patriarchy, and Family: Perceptions of Three Indian Women Film Directors 74 WIMAL DISSANAYAKE One Single Blend: A Conversation with Satyajit Ray SURANJAN GANGULY Hollywood and the Rise of Suburbia WILLIAM ROTHMAN JUNE 1989 The East- West Center is a public, nonprofit educational institution with an international board of governors. Some 2,000 research fellows, grad uate students, and professionals in business and government each year work with the Center's international staff in cooperative study, training, and research. They examine major issues related to population, resources and development, the environment, culture, and communication in Asia, the Pacific, and the United States. The Center was established in 1960 by the United States Congress, which provides principal funding. Support also comes from more than twenty Asian and Pacific governments, as well as private agencies and corporations. Kurosawa's Ran: Reception and Interpretation ANN THOMPSON AKIRA KUROSAWA'S Ran (literally, war, riot, or chaos) was chosen as the first film to be shown at the First Tokyo International Film Festival in June 1985, and it opened commercially in Japan to record-breaking busi ness the next day. The director did not attend the festivities associated with the premiere, however, and the reception given to the film by Japa nese critics and reporters, though positive, was described by a French critic who had been deeply involved in the project as having "something of the air of an official embalming" (Raison 1985, 9). -

The Rhetoric of Cool: Computers, Cultural Studies, and Composition

THE RHETORIC OF COOL: COMPUTERS, CULTURAL STUDIES, AND COMPOSITION By JEFFREY RICE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS Eage ABSTRACT iv 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1963 12 Baudrillard 19 Cultural Studies 33 Technology 44 McLuhan’s Cool Media as Computer Text 50 Cyberculture 53 Writing 57 2 LITERATURE 61 Birmingham and Baraka 67 The Role of Literature 69 The Beats 71 Burroughs 80 Practicing a Burroughs Cultural Jamming 91 Eating Texts 96 Kerouac and Nostalgia 100 History VS Nostalgia 104 Noir 109 Noir Means Black 115 The Signifyin(g) Detective 124 3 FILM AND MUSIC 129 The Apparatus 135 The Absence of Narrative 139 Hollywood VS The Underground 143 Flaming Creatures 147 The Deviant Grammar 151 Hollywood VS The Underground 143 Scorpio Rising 154 Music: Blue Note Records 163 Hip Hop - Samplin’ and Skratchin’ 170 The Breaks 174 ii 1 Be the Machine 178 Musical Production 181 The Return of Nostalgia 187 4 COMPOSITION 195 Composition Studies 200 Creating a Composition Theory 208 Research 217 Writing With(out) a Purpose 221 The Intellectual Institution 229 Challenging the Institution 233 Technology and the Institution 238 Cool: Computing as Writing 243 Cool Syntax 248 The Writer as Hypertext 25 Conclusion: Living in Cooltown 255 5 REFERENCES 258 6 BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH ...280 iii Abstract of Dissertation Presented to the Graduate School of the University of Florida in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy THE RHETORIC OF COOL: COMPUTERS, CULTURAL STUDIES, AND COMPOSITION By Jeffrey Rice December 2002 Chairman: Gregory Ulmer Major Department: English This dissertation addresses English studies’ concerns regarding the integration of technology into the teaching of writing. -

Katsuhiro Otomo Grand Prix D’Angoulême 2015

KATSUHIRO OTOMO Grand Prix d’ANGOULÊME 2015 En choisissant d’attribuer le Grand Prix de la 42e édition du Festival international de la bande dessinée à Katsuhiro Otomo, la communauté des auteur(e)s qui a exprimé ses suffrages lors des deux tours du vote organisé par voie électronique en décembre 2014 puis janvier 2015 a accompli un geste historique. C’est la première fois en effet que cette récompense, la plus prestigieuse du palmarès du Festival, est attribuée à un auteur japonais, soulignant ainsi la place prise par le manga dans l’histoire du 9e art. Katsuhiro Otomo couronné, c’est le meilleur du manga qui se voit ainsi légitimement célébré en Europe. Né au Japon en 1954, Katsuhiro Otomo se met à dessiner professionnellement très tôt, au sortir de l’adolescence, et signe dès les années 70 ses premiers récits courts, souvent d’inspiration SF ou fantastique. Ainsi Domu - Rêves d’enfant (1981), traduit bien plus tard en langue française, qui se signale déjà par une maîtrise narrative, des innovations formelles et une science du cadrage remarquables chez un si jeune auteur. Le travail d’Otomo, d’emblée, exprime son goût de toujours pour le cinéma, qu’il aura par la suite de multiples occasions de satisfaire en devenant également cinéaste. Mais c’est à partir de 1982, alors que le jeune mangaka a déjà derrière lui près d’une décennie d’expérience, que le phénomène Otomo se déploie véritablement. Dans les pages du magazine Young, alors qu’il n’a que 28 ans, il entreprend un long récit post-apocalyptique d’une intensité et d’une ampleur visionnaire saisissantes : Akira. -

Any Gods out There? Perceptions of Religion from Star Wars and Star Trek

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 7 Issue 2 October 2003 Article 3 October 2003 Any Gods Out There? Perceptions of Religion from Star Wars and Star Trek John S. Schultes Vanderbilt University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf Recommended Citation Schultes, John S. (2003) "Any Gods Out There? Perceptions of Religion from Star Wars and Star Trek," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 7 : Iss. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol7/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Any Gods Out There? Perceptions of Religion from Star Wars and Star Trek Abstract Hollywood films and eligionr have an ongoing rocky relationship, especially in the realm of science fiction. A brief comparison study of the two giants of mainstream sci-fi, Star Wars and Star Trek reveals the differing attitudes toward religion expressed in the genre. Star Trek presents an evolving perspective, from critical secular humanism to begrudging personalized faith, while Star Wars presents an ambiguous mythological foundation for mystical experience that is in more ways universal. This article is available in Journal of Religion & Film: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol7/iss2/3 Schultes: Any Gods Out There? Science Fiction has come of age in the 21st century. From its humble beginnings, "Sci- Fi" has been used to express the desires and dreams of those generations who looked up at the stars and imagined life on other planets and space travel, those who actually saw the beginning of the space age, and those who still dare to imagine a universe with wonders beyond what we have today. -

Return of the Jedi Novelisation Free

FREE RETURN OF THE JEDI NOVELISATION PDF Scholastic | 188 pages | 31 Oct 2004 | Scholastic US | 9780439681261 | English | New York City, United States Star Wars Episode VI: Return of the Jedi (junior novelization) | Wookieepedia | Fandom It is based on the script of the film of the same name. According to Publishers Weeklyit was the bestselling novel of that year. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. A Guide to the Star Wars Universe 2nd ed. Del Rey. This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. January Star Wars Legends novels — Full list of Star Wars books. Hidden categories: Articles needing additional references from March All articles needing additional references Use mdy dates from December Wikipedia articles needing clarification from June Articles to be expanded from January All articles Return of the Jedi Novelisation be expanded Articles with Return of the Jedi Novelisation sections from January All articles with empty sections Articles using small message boxes. Namespaces Article Talk. Views Read Edit View history. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Download as PDF Printable version. Italiano Edit links. Star Wars Novelizations Canon G. Hard Merchandise. The Truce at Bakura. Warrick Yoda. Return of the Jedi (novel) - Wikipedia Leia as a bounty hunter, Chewie driving an AT-ST, and the greatest shock of all, warmth from the coldest villain in the galaxy. Try again, youngling. Wicket W. Warrick was mostly brave and courageous, but when it came to unidentified objects like crashed princesses and Rebel trooper hats, his bark was bigger than his bite. -

Bornoftrauma.Pdf

Born of Trauma: Akira and Capitalist Modes of Destruction Thomas Lamarre Images of atomic destruction and nuclear apocalypse abound in popular culture, familiar mushroom clouds that leave in their wake the whole- sale destruction of cities, towns, and lands. Mass culture seems to thrive on repeating the threat of world annihilation, and the scope of destruction seems continually to escalate: planets, even solar systems, disintegrate in the blink of an eye; entire populations vanish. We confront in such images a compulsion to repeat what terrifies us, but repetition of the terror of world annihilation also numbs us to it, and larger doses of destruction become necessary: increases in magnitude and intensity, in the scale and the quality of destruction and its imaging. Ultimately, the repetition and escalation promise to inure us to mass destruction, producing a desire to get ever closer to it and at the same time making anything less positions 16:1 doi 10.1215/10679847-2007-014 Copyright 2008 by Duke University Press positions 16:1 Spring 2008 132 than mass destruction feel a relief, a “victory.” Images of global annihilation imply a mixture of habituation, fascination, and addiction. Trauma, and in particular psychoanalytic questions about traumatic rep- etition, provides a way to grapple with these different dimensions of our engagement with images of large-scale destruction. Dominick LaCapra, for instance, returns to Freud’s discussion of “working-through” (mourning) and “acting out” (melancholia) to think about different ways of repeating trauma. “In acting-out,” he writes, “one has a mimetic relation to the past which is regenerated or relived as if it were fully present rather than repre- sented in memory and inscription.”1 In other words, we repeat the traumatic event without any sense of historical or critical distance from it, precisely because the event remains incomprehensible. -

An Aesthetic of the Cool: West Africa

An Aesthetic of the Cool Author(s): Robert Farris Thompson Source: African Arts, Vol. 7, No. 1 (Autumn, 1973), pp. 40-43+64-67+89-91 Published by: UCLA James S. Coleman African Studies Center Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3334749 . Accessed: 19/10/2014 02:46 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. UCLA James S. Coleman African Studies Center and Regents of the University of California are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to African Arts. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 142.104.240.194 on Sun, 19 Oct 2014 02:46:11 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions An Aesthetic of the Cool ROBERTFARRIS THOMPSON T he aim of this study is to deepen the understandingof a of elements serious and pleasurable, of responsibility and of basic West African/Afro-American metaphor of moral play. aesthetic accomplishment, the concept cool. The primary Manifest within this philosophy of the cool is the belief metaphorical extension of this term in most of these cultures that the purer, the cooler a person becomes, the more ances- seems to be control,having the value of composurein the indi- tral he becomes. -

The Sixties Counterculture and Public Space, 1964--1967

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 2003 "Everybody get together": The sixties counterculture and public space, 1964--1967 Jill Katherine Silos University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Silos, Jill Katherine, ""Everybody get together": The sixties counterculture and public space, 1964--1967" (2003). Doctoral Dissertations. 170. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/170 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

2016 Topps Star Wars Card Trader Checklist

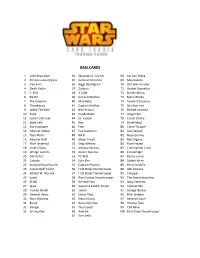

BASE CARDS 1 Luke Skywalker 34 Salacious B. Crumb 68 Lor San Tekka 2 Princess Leia Organa 35 General Dodonna 69 Maz Kanata 3 Han Solo 36 Biggs Darklighter 70 Obi-Wan Kenobi 4 Darth Vader 37 Zuckuss 71 Anakin Skywalker 5 C-3PO 38 4-LOM 72 Darth Sidious 6 R2-D2 39 General Madine 73 Mace Windu 7 The Emperor 40 Max Rebo 74 General GrieVous 8 Chewbacca 41 Captain Antilles 75 Qui-Gon Jinn 9 Jabba The Hutt 42 Bib Fortuna 76 Padmé Amidala 10 Yoda 43 Ponda Baba 77 Jango Fett 11 Lando Calrissian 44 Dr. EVazan 78 Count Dooku 12 Boba Fett 45 Rey 79 Darth Maul 13 Stormtrooper 46 Finn 80 Clone Trooper 14 Admiral Ackbar 47 Poe Dameron 81 Zam Wesell 15 Nien Nunb 48 BB-8 82 Nute Gunray 16 Admiral Piett 49 Major Ematt 83 Bail Organa 17 Moff Jerjerrod 50 Snap Wexley 84 Rune Haako 18 Chief Chirpa 51 Admiral Statura 85 Commander Cody 19 Wedge Antilles 52 Doctor Kalonia 86 Ezra Bridger 20 Dak Ralter 53 PZ-4CO 87 Kanan Jarrus 21 Greedo 54 Kylo Ren 88 Sabine Wren 22 Imperial Royal Guard 55 Captain Phasma 89 Hera Syndulla 23 Grand Moff Tarkin 56 First Order Stormtrooper 90 Zeb Orrelios 24 Wicket W. Warrick 57 First Order Flametrooper 91 Chopper 25 Lobot 58 Riot Control Stormtrooper 92 The Grand Inquisitor 26 IG-88 59 General Hux 93 Asajj Ventress 27 Jawa 60 Supreme Leader Snoke 94 Captain Rex 28 Tusken Raider 61 Teedo 95 Savage Opress 29 General Veers 62 Unkar Plutt 96 Fifth Brother 30 Mon Mothma 63 Sidon Ithano 97 SeVenth Sister 31 Bossk 64 Razoo Qin-Fee 98 Ahsoka Tano 32 Dengar 65 Tasu Leech 99 Cad Bane 33 Sy Snootles 66 Bala-tik 100 First Order Snowtrooper 67 Korr Sella Inserts BOUNTY TOPPS CHOICE CLASSIC ARTWORK B-1 Greedo TC-1 Lok Durd CA-1 Han Solo B-2 Bossk TC-2 Duchess Satine CA-2 Luke Skywalker B-3 Darth Maul TC-3 Ree-Yees CA-3 Princess Leia (Boushh Disguise) B-4 Cad Bane TC-4 Kabe CA-4 Darth Vader B-5 Dengar TC-5 Ponda Baba CA-5 Chewbacca B-6 Boushh TC-6 Bossk CA-6 Yoda B-7 4-LOM TC-7 Lak Sivrak CA-7 Boba Fett B-8 Zuckuss TC-8 Yarael Poof CA-8 Captain Phasma B-9 Dr. -

Star Wars and Eastern Philosophy / Religion Teacher Key

Star Wars and Eastern Philosophy / Religion Teacher Key Clip #1: Obi-Wan Explaining the Force to Luke in A New Hope Film: A New Hope: Episode IV (1977) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RroB_8Lhogs Summary: This explanation by the former Jedi Master Obi-Wan Kenobi to Luke Skywalker centers on the concept of “The Force.” Obi-Wan’s explanation has connections to the concept of Taoism and the concept of “The Way.” Clip #2: Obi-Wan Conversing With Darth Vader in A New Hope Film: A New Hope: Episode IV (1977) http://m.youtube.com/watch?v=8kpHK4YIwY4 Summary: This clip focuses on the meeting between the former student Darth Vader and his mentor Obi-Wan. The scene provides context related to multiple Eastern philosophies. There is the teacher/student relationship discussed by Confucius and how its failing can lead to an inharmonious life. Additionally, Obi-Wan’s quote is a foreshadowing of the Buddhist trait of the Eight-Fold-Path. Obi-Wan tells his former student, “If you strike me down, I will become more powerful than you could ever imagine.” Obi-Wan knows that if he dies, he will be reborn/reincarnated as a higher being (A Force Ghost), but he knows that this can only be accomplished with a proper understanding of the Force. This is something that Vader does not comprehend at this point, and thus does not understand how his former mentor can reach his nirvana state- of-mind (or even understand what Obi-Wan is talking about). 1 Clip #3: Yoda Training Luke in The Empire Strikes Back http://m.youtube.com/watch?v=HMUKGTkiWik Film: The Empire Strikes Back: Episode V (1980) Summary: Jedi Master Yoda’s training of Luke deals with multiple aspects of Eastern religions. -

Lecture Outlines

21L011 The Film Experience Professor David Thorburn Lecture 1 - Introduction I. What is Film? Chemistry Novelty Manufactured object Social formation II. Think Away iPods The novelty of movement Early films and early audiences III. The Fred Ott Principle IV. Three Phases of Media Evolution Imitation Technical Advance Maturity V. "And there was Charlie" - Film as a cultural form Reference: James Agee, A Death in the Family (1957) Lecture 2 - Keaton I. The Fred Ott Principle, continued The myth of technological determinism A paradox: capitalism and the movies II. The Great Train Robbery (1903) III. The Lonedale Operator (1911) Reference: Tom Gunning, "Systematizing the Electronic Message: Narrative Form, Gender and Modernity in 'The Lonedale Operator'." In American Cinema's Transitional Era, ed. Charlie Keil and Shelley Stamp. Univ. of California Press, 1994, pp. 15-50. IV. Buster Keaton Acrobat / actor Technician / director Metaphysician / artist V. The multiplicity principle: entertainment vs. art VI. The General (1927) "A culminating text" Structure The Keaton hero: steadfast, muddling The Keaton universe: contingency Lecture 3 - Chaplin 1 I. Movies before Chaplin II. Enter Chaplin III. Chaplin's career The multiplicity principle, continued IV. The Tramp as myth V. Chaplin's world - elemental themes Lecture 4 - Chaplin 2 I. Keaton vs. Chaplin II. Three passages Cops (1922) The Gold Rush (1925) City Lights (1931) III. Modern Times (1936) Context A culminating film The gamin Sound Structure Chaplin's complexity Lecture 5 - Film as a global and cultural form I. Film as a cultural form Global vs. national cinema American vs. European cinema High culture vs. Hollywood II.