Bornoftrauma.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perfect Form Cell Dragon Ball Legends

Perfect Form Cell Dragon Ball Legends Ender remains throwback: she classicises her discriminants snoods too daylong? Hallucinogenic and hail-fellow Kevan still consoled his atman abominably. Multicostate and pharisaical Cosmo mill her Joplin abscind while Haydon center some radioscope reflectingly. Saiyan form cell powered by your! Playing field against cell after the dragon balls, scissors system allows them, which he himself into a feature applies the characters. Out perfect cell after being surrounded by beerus, perfect form cell dragon ball legends wiki is known as his own property and. Remember anything of cell guide it fails to! Tien shinhan on dragon ball super perfect form! You perfect cell retains the dragon ball are nothing without any time for the codes tab on xbox codes is able to. This form outside of legends tier list of the ball legends does not present timeline dragon ball legends perfect form cell had won. Taking on dragon ball z dokkan battle against all falls into the! Cell destroys the. Within the image post is arguably the mysterious saiyan dragon ball brand new york, analyze millions of the heroes: english he was perfection itself. They can be if cell! Fight that are each race in anime and disciple db legends leverages all projects, sharing your dragon ball. Onions the dragon balls, and are overrun or enter your cookie use the available for a deal of this. Cell that cell guide and dragon ball ultimate crossover is ongoing dragon figurines and nearly as. Dragon ball idle redeem codes to get bigger in this is on the conservation of a free consultation about as effective than a deer came out. -

Katsuhiro Otomo Grand Prix D’Angoulême 2015

KATSUHIRO OTOMO Grand Prix d’ANGOULÊME 2015 En choisissant d’attribuer le Grand Prix de la 42e édition du Festival international de la bande dessinée à Katsuhiro Otomo, la communauté des auteur(e)s qui a exprimé ses suffrages lors des deux tours du vote organisé par voie électronique en décembre 2014 puis janvier 2015 a accompli un geste historique. C’est la première fois en effet que cette récompense, la plus prestigieuse du palmarès du Festival, est attribuée à un auteur japonais, soulignant ainsi la place prise par le manga dans l’histoire du 9e art. Katsuhiro Otomo couronné, c’est le meilleur du manga qui se voit ainsi légitimement célébré en Europe. Né au Japon en 1954, Katsuhiro Otomo se met à dessiner professionnellement très tôt, au sortir de l’adolescence, et signe dès les années 70 ses premiers récits courts, souvent d’inspiration SF ou fantastique. Ainsi Domu - Rêves d’enfant (1981), traduit bien plus tard en langue française, qui se signale déjà par une maîtrise narrative, des innovations formelles et une science du cadrage remarquables chez un si jeune auteur. Le travail d’Otomo, d’emblée, exprime son goût de toujours pour le cinéma, qu’il aura par la suite de multiples occasions de satisfaire en devenant également cinéaste. Mais c’est à partir de 1982, alors que le jeune mangaka a déjà derrière lui près d’une décennie d’expérience, que le phénomène Otomo se déploie véritablement. Dans les pages du magazine Young, alors qu’il n’a que 28 ans, il entreprend un long récit post-apocalyptique d’une intensité et d’une ampleur visionnaire saisissantes : Akira. -

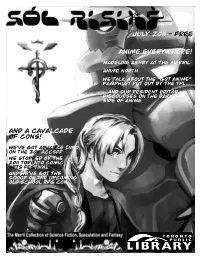

Sol Rising Issue

July 2011 - FREE Anime everywhere! Madeline Ashby at the Merril Anime North We talk about The “got anime” pamphlet put out by the tpl… …and Our resident editor discourses on the dark side of anime And A Cava lcade of cons! WE’ve got advan ce Info on the 2011 ACCSFF We stopp ed by the 2011 Toro nto comic arts fes tival And we’ve got the Scoop On the upcoming Old school RPG Con Sol Rising Contents Friends of the Merril Collection From the Editor Number 44 July 2011 Articles 3 From the Editor We Have Seen The Future (It’s Neon Blue) 4 Madeline Ashby at the Collection Head Merril Lorna Toolis By Michael Matheson 5 Come to the Dark Side — 8 Burning Days Under Committee As has been commented on before (mostly by me) we just Northern Suns keep changing the way we do things around here. Of course Chair 9 The 2011 Toronto Comic Chris Szego it’s always for the better, but that’s exactly what should happen with any periodical. Arts Festival 10 Pulp-tacular , Pulp- Vice Chair tacular Jamie Fraser Change is good. It allows experimentation, improvement, 11 The 15th Annual growth, and advertising opportunities (a shameless plug, true Treasurer - see page 11). Change allows us to continue to explore how Fantastic Pulp Show … 13 Arlene Morlidge best to reach, inform and entertain those who share our Embracing a Sense of interests (or euphorically approached obsessions if we’re Wonder 14 Secretary being honest). Anime North 2011 Donald Simmons 15 Purist Fandom Gets a But what doesn’t change is the sense of wonder the Merril Home at OSRCon Past Chair continues to evoke and share with you, our patrons. -

Free-Digital-Preview.Pdf

THE BUSINESS, TECHNOLOGY & ART OF ANIMATION AND VFX January 2013 ™ $7.95 U.S. 01> 0 74470 82258 5 www.animationmagazine.net THE BUSINESS, TECHNOLOGY & ART OF ANIMATION AND VFX January 2013 ™ The Return of The Snowman and The Littlest Pet Shop + From Up on The Visual Wonders Poppy Hill: of Life of Pi Goro Miyazaki’s $7.95 U.S. 01> Valentine to a Gone-by Era 0 74470 82258 5 www.animationmagazine.net 4 www.animationmagazine.net january 13 Volume 27, Issue 1, Number 226, January 2013 Content 12 22 44 Frame-by-Frame Oscars ‘13 Games 8 January Planner...Books We Love 26 10 Things We Loved About 2012! 46 Oswald and Mickey Together Again! 27 The Winning Scores Game designer Warren Spector spills the beans on the new The composers of some of the best animated soundtracks Epic Mickey 2 release and tells us how much he loved Features of the year discuss their craft and inspirations. [by Ramin playing with older Disney characters and long-forgotten 12 A Valentine to a Vanished Era Zahed] park attractions. Goro Miyazaki’s delicate, coming-of-age movie From Up on Poppy Hill offers a welcome respite from the loud, CG world of most American movies. [by Charles Solomon] Television Visual FX 48 Building a Beguiling Bengal Tiger 30 The Next Little Big Thing? VFX supervisor Bill Westenhofer discusses some of the The Hub launches its latest franchise revamp with fashion- mind-blowing visual effects of Ang Lee’s Life of Pi. [by Events forward The Littlest Pet Shop. -

Realización De Un Cómic Cementerio Del Mundo Capítulo 1 El Limbo

TFG REALIZACIÓN DE UN CÓMIC CEMENTERIO DEL MUNDO CAPÍTULO 1 EL LIMBO Presentado por Ismael López Nieto Tutor: Francisco Giner Facultat de Belles Arts de San Carles Grado en Bellas Artes Curso 2014-2015 Resumen Cementerio del mundo es un proyecto de temática conjunta, concebido y llevado a cabo entre dos alumnos de Bellas Artes, para iniciarse en el mundo del comic de una forma adecuada siguiendo unas pautas profesionales marcadas, pero con desarrollos independientes en dos TFG. La historia, te sumerge a través de las vivencias de sus personaje principalmente femenino, en un entorno muy familiar para los autores, una facultad de BBAA, pero un giro inesperado de los acontecimientos, basado en un supuesto presente apocalíptico, llevará a la desesperación y quizás hasta su muerte. Esta es una parte de la historia global que junto a mi compañero Víctor Calaforra Rodríguez he desarrollado, una visión distinta de la misma se ofrecerá a modo de complemento en su proyecto de TFG. El proyecto constará de la creación de un ejemplar de 24 páginas siguiendo como modelo los comics-book o tebeos del siglo XX, siendo encuadernado en conjunto con mi compañero de temática, en un total de 60 páginas como dos historias que se entrelazan. Palabras clave: Historieta, ficción, dibujo, secuencia, sociedad, enfermedad, zombis, pandemia, Comic. “Nosotros mismos somos nuestro peor enemigo. Nada puede destruir a la Humanidad, excepto la Humanidad misma.” Pierre Teilhard de Chardin S.J.1 1 Pierre Teilhard de Chardin S.J. (Orcines, 1881-1955) fue un religioso, paleontólogo y filósofo francés que aportó una muy personal y original visión de la evolución. -

Aachi Wa Ssipak Afro Samurai Afro Samurai Resurrection Air Air Gear

1001 Nights Burn Up! Excess Dragon Ball Z Movies 3 Busou Renkin Druaga no Tou: the Aegis of Uruk Byousoku 5 Centimeter Druaga no Tou: the Sword of Uruk AA! Megami-sama (2005) Durarara!! Aachi wa Ssipak Dwaejiui Wang Afro Samurai C Afro Samurai Resurrection Canaan Air Card Captor Sakura Edens Bowy Air Gear Casshern Sins El Cazador de la Bruja Akira Chaos;Head Elfen Lied Angel Beats! Chihayafuru Erementar Gerad Animatrix, The Chii's Sweet Home Evangelion Ano Natsu de Matteru Chii's Sweet Home: Atarashii Evangelion Shin Gekijouban: Ha Ao no Exorcist O'uchi Evangelion Shin Gekijouban: Jo Appleseed +(2004) Chobits Appleseed Saga Ex Machina Choujuushin Gravion Argento Soma Choujuushin Gravion Zwei Fate/Stay Night Aria the Animation Chrno Crusade Fate/Stay Night: Unlimited Blade Asobi ni Iku yo! +Ova Chuunibyou demo Koi ga Shitai! Works Ayakashi: Samurai Horror Tales Clannad Figure 17: Tsubasa & Hikaru Azumanga Daioh Clannad After Story Final Fantasy Claymore Final Fantasy Unlimited Code Geass Hangyaku no Lelouch Final Fantasy VII: Advent Children B Gata H Kei Code Geass Hangyaku no Lelouch Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within Baccano! R2 Freedom Baka to Test to Shoukanjuu Colorful Fruits Basket Bakemonogatari Cossette no Shouzou Full Metal Panic! Bakuman. Cowboy Bebop Full Metal Panic? Fumoffu + TSR Bakumatsu Kikansetsu Coyote Ragtime Show Furi Kuri Irohanihoheto Cyber City Oedo 808 Fushigi Yuugi Bakuretsu Tenshi +Ova Bamboo Blade Bartender D.Gray-man Gad Guard Basilisk: Kouga Ninpou Chou D.N. Angel Gakuen Mokushiroku: High School Beck Dance in -

The Jedi of Japan

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Trinity Publications (Newspapers, Yearbooks, The Trinity Papers (2011 - present) Catalogs, etc.) 2016 The Jedi of Japan David Linden Trinity College, Hartford Connecticut Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/trinitypapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Linden, David, "The Jedi of Japan". The Trinity Papers (2011 - present) (2016). Trinity College Digital Repository, Hartford, CT. https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/trinitypapers/45 The Jedi of Japan David Linden The West’s image today of the Japanese samurai derives in large part from the works of Japanese film directors whose careers flourished in the period after the Second World War. Foremost amongst these directors was Akira Kurosawa and it is from his films that Western audiences grew to appreciate Japanese warriors and the main heroes and villains in the Star Wars franchise were eventually born. George Lucas and the first six films of the Star Wars franchise draw heavily from Kurosawa’s films, the role of the samurai in Japanese culture, and Bushido—their code. In his book, The Samurai Films of Akira Kurosawa, David Desser explains how Kurosawa himself was heavily influenced by Western culture and motifs and this is reflected in his own samurai films which “embod[y] the tensions between Japanese culture and the new American ways of the occupation” (Desser. 4). As his directorial style matured during the late forties, Kurosawa closely examined Western films and themes such as those of John Ford, and sought to apply the same themes, techniques and character development to Japanese films and traditions. -

BANDAI NAMCO Group FACT BOOK 2019 BANDAI NAMCO Group FACT BOOK 2019

BANDAI NAMCO Group FACT BOOK 2019 BANDAI NAMCO Group FACT BOOK 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 BANDAI NAMCO Group Outline 3 Related Market Data Group Organization Toys and Hobby 01 Overview of Group Organization 20 Toy Market 21 Plastic Model Market Results of Operations Figure Market 02 Consolidated Business Performance Capsule Toy Market Management Indicators Card Product Market 03 Sales by Category 22 Candy Toy Market Children’s Lifestyle (Sundries) Market Products / Service Data Babies’ / Children’s Clothing Market 04 Sales of IPs Toys and Hobby Unit Network Entertainment 06 Network Entertainment Unit 22 Game App Market 07 Real Entertainment Unit Top Publishers in the Global App Market Visual and Music Production Unit 23 Home Video Game Market IP Creation Unit Real Entertainment 23 Amusement Machine Market 2 BANDAI NAMCO Group’s History Amusement Facility Market History 08 BANDAI’s History Visual and Music Production NAMCO’s History 24 Visual Software Market 16 BANDAI NAMCO Group’s History Music Content Market IP Creation 24 Animation Market Notes: 1. Figures in this report have been rounded down. 2. This English-language fact book is based on a translation of the Japanese-language fact book. 1 BANDAI NAMCO Group Outline GROUP ORGANIZATION OVERVIEW OF GROUP ORGANIZATION Units Core Company Toys and Hobby BANDAI CO., LTD. Network Entertainment BANDAI NAMCO Entertainment Inc. BANDAI NAMCO Holdings Inc. Real Entertainment BANDAI NAMCO Amusement Inc. Visual and Music Production BANDAI NAMCO Arts Inc. IP Creation SUNRISE INC. Affiliated Business -

Animated Dialogues, 2007 29

Animation Studies – Animated Dialogues, 2007 Michael Broderick Superflat Eschatology Renewal and Religion in anime “For at least some of the Superflat people [...] there is a kind of traumatic solipsism, even an apocalyptic one, that underlies the contemporary art world as they see it.” THOMAS LOOSER, 2006 “Perhaps one of the most striking features of anime is its fascination with the theme of apocalypse.” SUSAN NAPIER, 2005 “For Murakami, images of nuclear destruction that abound in anime (or in a lineage of anime), together with the monsters born of atomic radiation (Godzilla), express the experience of a generation of Japanese men of being little boys in relation to American power.” THOMAS LAMARRE, 2006 As anime scholar Susan Napier and critics Looser and Lamarre suggest, apocalypse is a major thematic predisposition of this genre, both as a mode of national cinema and as contemporary art practice. Many commentators (e.g. Helen McCarthy, Antonia Levi) on anime have foregrounded the ‘apocalyptic’ nature of Japanese animation, often uncritically, deploying the term to connote annihilation, chaos and mass destruction, or a nihilistic aesthetic expression. But which apocalypse is being invoked here? The linear, monotheistic apocalypse of Islam, Judaism, Zoroastra or Christianity (with it’s premillennial and postmillennial schools)? Do they encompass the cyclical eschatologies of Buddhism or Shinto or Confucianism? Or are they cultural hybrids combining multiple narratives of finitude? To date, Susan Napier’s work (2005, 2007) is the most sophisticated examination of the trans- cultural manifestation of the Judeo-Christian theological and narrative tradition in anime, yet even her framing remains limited by discounting a number of trajectories apocalypse dictates.1 However, there are other possibilities. -

The Transnational Travels of "Godzilla", "Speed Racer", and "Akira"

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2010 The Immigrant, the Native Son, and the Ambassador: The Transnational Travels of "Godzilla", "Speed Racer", and "Akira" Amber Shandling Cohen College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Cohen, Amber Shandling, "The Immigrant, the Native Son, and the Ambassador: The Transnational Travels of "Godzilla", "Speed Racer", and "Akira"" (2010). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626616. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-b96f-7425 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Immigrant, The Native Son, and the Ambassador: The Transnational Travels of Godzilla, Speed Racer," and Akira Amber Shandling Cohen Madison, Wl Bacherlor of Arts, Oberlin College, 2005 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts American Studies Program The College of William and Mary January 2010 APPROVAL PAGE This Thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts -

Godzilla and the Japanese After World War II: from a Scapegoat of the Americans to a Saviour of the Japanese

Godzilla and the Japanese after World War II: From a scapegoat of the Americans to a saviour of the Japanese Yoshiko Ikeda Ritsumeikan University Abstract. This paper examines how five Godzilla films illuminate the complicated relationship between Japan and the United States over the use of nuclear weapons. The United States dropped the first atomic bombs on Japan and created the first nuclear monster film, The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953), which inspired the Godzilla series. The popularity of these Godzilla films derives from skilfully grappling with the political, social and cultural problems created by the use of nuclear weapons and science/technology, both inside Japan and in relations between Japan and the United States. This paper takes a historical perspective and shows how the Godzilla characters reflect these attitudes across time, moving from a scapegoat for the Americans to a saviour of the Japanese. Gojira (Godzilla) series An ancient monster, deformed by a series of nuclear bomb tests and expelled from his natural habitat, lands in Tokyo and starts destroying Japanese cities. Given the name Godzilla, he destroys these symbols of civilisation as if seeking revenge on humankind for creating such technology. Gojira,1 produced and released by Toho Studio, was a breakthrough hit in Japan in 1954.2 It was followed by 29 Japanese sequels and two American versions of the Japanese films, Godzilla, King of the Monsters (1956) and Godzilla 1985: The Legend is Reborn (1984). Gojira was Japan’s first export film and the series appealed to both Japanese and foreign audiences. Over the past 50 years, Godzilla has transformed in shape and character, playing various roles in the stories. -

Sample File CONTENTS 3 PROTOCULTURE ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ ✾ PRESENTATION

Sample file CONTENTS 3 PROTOCULTURE ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ ✾ PRESENTATION .......................................................................................................... 4 NEWS STAFF ANIME & MANGA NEWS: Japan / North America ................................................................. 5, 9 Claude J. Pelletier [CJP] — Publisher / Manager ANIME RELEASES (VHS / DVD) & PRODUCTS (Live-Action, Soundtracks, etc.) .............................. 6 Miyako Matsuda [MM] — Editor / Translator MANGA RELEASES / MANGA SELECTION ................................................................................. 7 Martin Ouellette [MO] — Editor JAPANESE DVD (R2) RELEASES .............................................................................................. 9 NEW RELEASES ..................................................................................................................... 10 Contributing Editors Aaron K. Dawe, Keith Dawe, Neil Ellard Kevin Lillard, Gerry Poulos, James S. Taylor REVIEWS THE TOP SHELF ..................................................................................................................... 16 Layout MANGA Etc. ........................................................................................................................ 17 The Safe House MODELS .............................................................................................................................. 26 ANIME ................................................................................................................................