PDF-Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crimes Act 2016

REPUBLIC OF NAURU Crimes Act 2016 ______________________________ Act No. 18 of 2016 ______________________________ TABLE OF PROVISIONS PART 1 – PRELIMINARY ....................................................................................................... 1 1 Short title .................................................................................................... 1 2 Commencement ......................................................................................... 1 3 Application ................................................................................................. 1 4 Codification ................................................................................................ 1 5 Standard geographical jurisdiction ............................................................. 2 6 Extraterritorial jurisdiction—ship or aircraft outside Nauru ......................... 2 7 Extraterritorial jurisdiction—transnational crime ......................................... 4 PART 2 – INTERPRETATION ................................................................................................ 6 8 Definitions .................................................................................................. 6 9 Definition of consent ................................................................................ 13 PART 3 – PRINCIPLES OF CRIMINAL RESPONSIBILITY ................................................. 14 DIVISION 3.1 – PURPOSE AND APPLICATION ................................................................. 14 10 Purpose -

Competing Theories of Blackmail: an Empirical Research Critique of Criminal Law Theory

Competing Theories of Blackmail: An Empirical Research Critique of Criminal Law Theory Paul H. Robinson,* Michael T. Cahill** & Daniel M. Bartels*** The crime of blackmail has risen to national media attention because of the David Letterman case, but this wonderfully curious offense has long been the favorite of clever criminal law theorists. It criminalizes the threat to do something that would not be criminal if one did it. There exists a rich liter- ature on the issue, with many prominent legal scholars offering their accounts. Each theorist has his own explanation as to why the blackmail offense exists. Most theories seek to justify the position that blackmail is a moral wrong and claim to offer an account that reflects widely shared moral intuitions. But the theories make widely varying assertions about what those shared intuitions are, while also lacking any evidence to support the assertions. This Article summarizes the results of an empirical study designed to test the competing theories of blackmail to see which best accords with pre- vailing sentiment. Using a variety of scenarios designed to isolate and test the various criteria different theorists have put forth as “the” key to blackmail, this study reveals which (if any) of the various theories of blackmail proposed to date truly reflects laypeople’s moral judgment. Blackmail is not only a common subject of scholarly theorizing but also a common object of criminal prohibition. Every American jurisdiction criminalizes blackmail, although there is considerable variation in its formulation. The Article reviews the American statutes and describes the three general approaches these provisions reflect. -

Conflict of the Criminal Statute of Limitations with Lesser Offenses at Trial

William & Mary Law Review Volume 37 (1995-1996) Issue 1 Article 10 October 1995 Conflict of the Criminal Statute of Limitations with Lesser Offenses at Trial Alan L. Adlestein Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the Criminal Law Commons Repository Citation Alan L. Adlestein, Conflict of the Criminal Statute of Limitations with Lesser Offenses at Trial, 37 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 199 (1995), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol37/iss1/10 Copyright c 1995 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr CONFLICT OF THE CRIMINAL STATUTE OF LIMITATIONS WITH LESSER OFFENSES AT TRIAL ALAN L. ADLESTEIN I. INTRODUCTION ............................... 200 II. THE CRIMINAL STATUTE OF LIMITATIONS AND LESSER OFFENSES-DEVELOPMENT OF THE CONFLICT ........ 206 A. Prelude: The Problem of JurisdictionalLabels ..... 206 B. The JurisdictionalLabel and the CriminalStatute of Limitations ................ 207 C. The JurisdictionalLabel and the Lesser Offense .... 209 D. Challenges to the Jurisdictional Label-In re Winship, Keeble v. United States, and United States v. Wild ..................... 211 E. Lesser Offenses and the Supreme Court's Capital Cases- Beck v. Alabama, Spaziano v. Florida, and Schad v. Arizona ........................... 217 1. Beck v. Alabama-LegislativePreclusion of Lesser Offenses ................................ 217 2. Spaziano v. Florida-Does the Due Process Clause Require Waivability? ....................... 222 3. Schad v. Arizona-The Single Non-Capital Option ....................... 228 F. The Conflict Illustrated in the Federal Circuits and the States ....................... 230 1. The Conflict in the Federal Circuits ........... 232 2. The Conflict in the States .................. 234 III. -

Digital Blackmail As an Emerging Tactic 2016

September 9 DIGITAL BLACKMAIL AS AN EMERGING TACTIC 2016 Digital Blackmail (DB) represents a severe and growing threat to individuals, small businesses, corporations, and government Examining entities. The rapid increase in the use of DB such as Strategies ransomware; the proliferation of variants and growth in their ease of use and acquisition by cybercriminals; weak defenses; Public and and the anonymous nature of the money trail will only increase Private Entities the scale of future attacks. Private sector, non-governmental organization (NGO), and government cybersecurity experts Can Pursue to were brought together by the Office of the Director of National Contain Such Intelligence and the Department of Homeland Security to determine emerging tactics and countermeasures associated Attacks with the threat of DB. In this paper, DB is defined as illicitly acquiring or denying access to sensitive data for the purpose of affecting victims’ behaviors. Threats may be made of lost revenue, the release of intellectual property or sensitive personnel/client information, the destruction of critical data, or reputational damage. For clarity, this paper maps DB activities to traditional blackmail behaviors and explores methods and tools, exploits, protection measures, whether to pay or not pay the ransom, and law enforcement (LE) and government points of contact for incident response. The paper also examines the future of the DB threat. Digital Blackmail as an Emerging Tactic Team Members Name Organization Caitlin Bataillon FBI Lynn Choi-Brewer -

Nebraska Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS)

Nebraska Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS) Manual for Automated Agencies November, 2000 Nebraska Commission on Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice 301 Centennial Mall South, P.O. Box 94946 Lincoln, Nebraska 68509-4946 (402) 471-2194 TABLE OF CONTENTS NEBRASKA INCIDENT-BASED REPORTING SYSTEM (NIBRS) ........................ 1 Definition of "Incident” ...................................................... 4 DATA REQUIREMENTS .......................................................... 7 Requirements for each Group A Offense ......................................... 8 Requirements for Arrests for Group A and Group B Offenses ......................... 15 DEFINITIONS OF BASIC CORE, ADDITIONAL DATA ELEMENT AND ARRESTEE ELEMENTS Age .................................................................... 17 Aggravated Assault / Homicide Circumstances .................................... 17 Armed With . 18 Arrest Date . 19 Arrest (Transaction) Number ................................................. 19 Arrest Offense Code ........................................................ 19 Attempted / Completed ..................................................... 19 Criminal Activity Type ..................................................... 20 Date Recovered ........................................................... 20 Disposition of Arrestee Under Age 18 .......................................... 20 Drug Type / Type Criminal Activity (Arrestee) ................................... 21 Estimated Drug Quantity / Type Drug Measurement .............................. -

Texas Law Review See Also

Texas Law Review See Also Response Taking It to the Streets Stuart P. Green* For more than fifty years, some of the best minds in criminal law theory have applied some of the most sophisticated tools of analysis in an effort to solve the seemingly insolvable blackmail paradox.1 Whether any of these theorists has been successful is debatable. In Competing Theories of Blackmail: An Empirical Research Critique of Criminal Law Theory, Paul Robinson, Michael Cahill, and Daniel Bartels advance the novel—dare I say, paradoxical—notion that one way to solve the problem is to ask a collection of laypersons, untutored in law or philosophy, what they think should count as blackmail.2 There is much about the article that is admirable: The way the authors derive concrete scenarios from abstract theories is ingenious; their summary of the various blackmail theories is a model of conciseness; the methodological techniques they use are exemplary. As is the norm for brief responses of this sort, however, I shall focus on what I perceive as the article’s shortcomings rather than its strengths. In so doing, I do not mean to minimize the authors’ achievement. * Professor of Law and Justice Nathan L. Jacobs Scholar, Rutgers School of Law–Newark. 1. The seminal piece is Glanville Williams, Blackmail, CRIM. L. REV. 79 (1954). See also, e.g., JOEL FEINBERG, HARMLESS WRONGDOING (1988); Mitchell N. Berman, The Evidentiary Theory of Blackmail: Taking Motives Seriously, 65 U. CHI. L. REV. 795 (1998); George P. Fletcher, Blackmail: The Paradigmatic Crime, 141 U. PA. L. REV. 1617 (1993); Leo Katz, Blackmail and Other Forms of Arm-Twisting, 141 U. -

Copyright, Spleens, Blackmail, and Insider Trading

California Law Review VOL. 80 DECEMBER 1992 No.6 Copyright © 1992 by California Law Review, Inc. A Theory of Law and Information: Copyright, Spleens, Blackmail, and Insider Trading James Boyle TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................... 1416 I. Four Puzzles ............................................ 1426 A. Copyright .......................................... 1426 B. Blackmail .......................................... 1428 C. Insider Trading ..................................... 1429 D. Spleens ............................................. 1429 II. Public and Private in the Liberal State ................... 1433 III. Information in the Liberal State ......................... 1437 IV. The Economics of Information .......................... 1443 V. Property in the Liberal State ............................ 1458 VI. Copyright .............................................. , 1461 VII. Blackmail ............................................... 1470 A. Economic Theories ................................. 1471 B. Libertarian Theories ................................ 1477 C. Third Party Theories ............................... 1481 D. Shared Problems ................................... 1483 VIII. Insider Trading ....................................' ..... 1488 A. Economic Analysis of Information Disparities ....... 1494 1. Baseline Errors. .. 1494 2. Ad Hoc Claims About Behavior ................. 1498 3. Ignoring Contradictions in the Theory ........... 1499 B. Insider Trading Law as a Puzzle ................... -

Informational Blackmail: Survived by Technicality? Chen Yehudai

Marquette Law Review Volume 92 Article 6 Issue 4 Summer 2009 Informational Blackmail: Survived by Technicality? Chen Yehudai Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Chen Yehudai, Informational Blackmail: Survived by Technicality?, 92 Marq. L. Rev. 779 (2009). Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr/vol92/iss4/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Law Review by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATIONAL BLACKMAIL: SURVIVED BY TECHNICALITY? CHEN YEHUDAI Blackmail constitutes one of the most intriguing puzzles in criminal law: How can two legal rights—i.e., a threat to disclose true but reputation-damaging information and, independently, a simple demand for money—make a legal wrong? The puzzle gets even more complicated when we take into account that it is not unlawful for one who holds embarrassing information to accept an offer of payment made by an unthreatened recipient in return for a promise not to disclose the information. In order to answer this question, this Article surveys and analyzes the development of the law of informational blackmail and criminal libel in English and American law and argues that the modern crime of blackmail is the result of an “historical accident” stemming from the historical classification of blackmail as a property offense instead of a reputation-protecting offense. The Article argues that when enacted, the prohibition on informational blackmail was meant to protect the interest of reputation as a supplement to the law of criminal libel. -

Monroe Freedman's Solution to the Criminal Defense Lawyer's

MONROE FREEDMAN’S SOLUTION TO THE CRIMINAL DEFENSE LAWYER’S TRILEMMA IS WRONG AS A MATTER OF POLICY AND CONSTITUTIONAL LAW* Stephen Gillers** I. INTRODUCTION Monroe Freedman has argued, most recently in the third edition of Understanding Lawyers’ Ethics , co-authored with Abbe Smith, that criminal defense lawyers have a “trilemma” because the rules of their profession give them potentially contradictory instructions. 1 First, competence requires lawyers to seek all information that can aid a client’s matter. 2 Second, lawyers have a duty of confidentiality that generally forbids them to use a client’s information except for the client’s benefit. 3 Third, lawyers have a duty of candor to the court that may require them to reveal a client’s confidential information in order to prevent or correct fraud on the court (which perjury would be). 4 Freedman believes that these three obligations cannot always co-exist, 5 and that is certainly true. Sometimes, a lawyer will have to sacrifice one obligation to fulfill another obligation. This trilemma is not limited to criminal defense lawyers, but Understanding Lawyers’ Ethics addresses only the criminal defense lawyer. Freedman argues that where the lawyer is defending a person accused of a crime, the ethics rules should subordinate the third obligation, candor to the court, to the other two obligations. 6 The upshot is that if a defense lawyer cannot dissuade a client from giving false testimony and cannot avoid aiding the perjury by * But we are indebted to him for raising the issue and making us think hard about the answer. -

First Draft of Report #43 – Blackmail

First Draft of Report #43 – Blackmail SUBMITTED FOR ADVISORY GROUP REVIEW November 20, 2019 DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CRIMINAL CODE REFORM COMMISSION 441 FOURTH STREET, NW, SUITE 1C001 SOUTH WASHINGTON, DC 20001 PHONE: (202) 442-8715 www.ccrc.dc.gov First Draft of Report #43 - Blackmail This Draft Report contains recommended reforms to District of Columbia criminal statutes for review by the D.C. Criminal Code Reform Commission’s statutorily designated Advisory Group. A copy of this document and a list of the current Advisory Group members may be viewed on the website of the D.C. Criminal Code Reform Commission at www.ccrc.dc.gov. This Draft Report has two parts: (1) draft statutory text for a new Title 22E of the D.C. Code; and (2) commentary on the draft statutory text. The commentary explains the meaning of each provision and considers whether existing District law would be changed by the provision (and if so, why this change is being recommended). Any Advisory Group member may submit written comments on any aspect of this Draft Report to the D.C. Criminal Code Reform Commission. The Commission will consider all written comments that are timely received from Advisory Group members. Additional versions of this Draft Report may be issued for Advisory Group review, depending on the nature and extent of the Advisory Group’s written comments. The D.C. Criminal Code Reform Commission’s final recommendations to the Council and Mayor for comprehensive criminal code reform will be based on the Advisory Group’s timely written comments and approved by a majority of the Advisory Group’s voting members. -

Blackmail: the Paradigmatic Crime

BLACKMAIL: THE PARADIGMATIC CRIME GEORGE P. FLETCHER* The ongoing debate about the rationale for punishing blackmail assumes that there is something odd about the crime. Why, the question goes, should demanding money to conceal embarrassing information be criminalized when there is nothing wrong with the separate acts of keeping silent or requesting payment for services rendered? Why should an innocent end (silence) coupled with a generally respectable means (monetary payment) constitute a crime? This supposed paradox, however, is not peculiar to blackmail. Many good acts are corrupted by doing them for a price. There is nothing wrong with government officials showing kindness or doing favors for their constituents, but doing them for a negotiated price becomes bribery. Sex is often desirable and permissible by itself, but if done in exchange for money, the act becomes prostitution. Confessing to a crime may be praiseworthy in some circumstances, but if the police pay the suspect to confess, the confession will undoubtedly be labelled involuntary and inadmissible. If there is a paradox in the crime of blackmail, these other practices of criminal justice should also strike us as self-contradictory. Contrary to the popular view in the literature, I wish to argue that blackmail is not an anomalous crime but rather a paradigm for understanding both criminal wrongdoing and punishment. That is an ambitious claim, one that requires at least a clear plan of exposition. My project is to seek "reflective equilibrium"1 across ten cases that are pivotal in the debates about the rationale for criminalizing blackmail. Reflective equilibrium requires a convinc- ing fit between the agreed-upon outcomes in the ten cases and general principles that can account for these outcomes. -

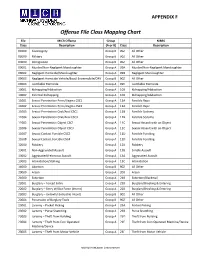

Offense File Class Mapping Chart

APPENDIX F Offense File Class Mapping Chart File MICR Offense Group NIBRS Class Description (A or B) Class Description 01000 Sovereignty Group B 90Z All Other 02000 Military Group B 90Z All Other 03000 Immigration Group B 90Z All Other 09001 Murder/Non‐Negligent Manslaughter Group A 09A Murder/Non‐Negligent Manslaughter 09002 Negligent Homicide/Manslaughter Group A 09B Negligent Manslaughter 09003 Negligent Homicide Vehicle/Boat/ Snowmobile/ORV Group B 90Z All Other 09004 Justifiable Homicide Group A 09C Justifiable Homicide 10001 Kidnapping/Abduction Group A 100 Kidnapping/Abduction 10002 Parental Kidnapping Group A 100 Kidnapping/Abduction 11001 Sexual Penetration Penis/Vagina CSC1 Group A 11A Forcible Rape 11002 Sexual Penetration Penis/Vagina CSC3 Group A 11A Forcible Rape 11003 Sexual Penetration Oral/Anal CSC1 Group A 11B Forcible Sodomy 11004 Sexual Penetration Oral/Anal CSC3 Group A 11B Forcible Sodomy 11005 Sexual Penetration Object CSC1 Group A 11C Sexual Assault with an Object 11006 Sexual Penetration Object CSC3 Group A 11C Sexual Assault with an Object 11007 Sexual Contact Forcible CSC2 Group A 11D Forcible Fondling 11008 Sexual Contact Forcible CSC4 Group A 11D Forcible Fondling 12000 Robbery Group A 120 Robbery 13001 Non‐Aggravated Assault Group A 13B Simple Assault 13002 Aggravated/Felonious Assault Group A 13A Aggravated Assault 13003 Intimidation/Stalking Group A 13C Intimidation 14000 Abortion Group B 90Z All Other 20000 Arson Group A 200 Arson 21000 Extortion Group A 210 Extortion/Blackmail 22001 Burglary – Forced