Informational Blackmail: Survived by Technicality? Chen Yehudai

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charging Language

1. TABLE OF CONTENTS Abduction ................................................................................................73 By Relative.........................................................................................415-420 See Kidnapping Abuse, Animal ...............................................................................................358-362,365-368 Abuse, Child ................................................................................................74-77 Abuse, Vulnerable Adult ...............................................................................78,79 Accessory After The Fact ..............................................................................38 Adultery ................................................................................................357 Aircraft Explosive............................................................................................455 Alcohol AWOL Machine.................................................................................19,20 Retail/Retail Dealer ............................................................................14-18 Tax ................................................................................................20-21 Intoxicated – Endanger ......................................................................19 Disturbance .......................................................................................19 Drinking – Prohibited Places .............................................................17-20 Minors – Citation Only -

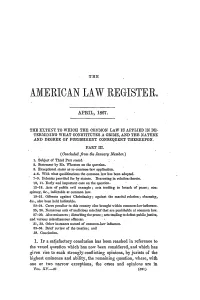

Extent to Which the Common Law Is Applied in Determining What

THE AMERICAN LAW REGISTER, APRIL, 1867. THE EXTE'N"IT TO WHICH THE COM ON LAW IS APPLIED IN DE- TERMINING WHAT CONSTITUTES A CRIME, AND THE NATURE AND DEGREE OF PUNISHMENT CONSEQUENT THEREUPON. PART III. (Concluded from the January.umber.) 1. Subject of Third. Part stated. 2. Statement by .Mr. Wheaton on tie question. 3. Exceptional states as to common-law application. 4-6. With what qualifications the common law has been adopted. 7-9. Felonies provided for by statute. Reasoning in relation thereto. 10, 11. Early and important case on the question. 12-18. Acts of public evil example; acts tending to breach of peace; con- -piracy, &c., indictable at common law. 19-21. Offences against Christianity; against the marital relation; obscenity, &c., also been held indictable. 22-24. Cases peculiar to this country also brought within common-law influence. 25, 26. 'Numerous acts of malicious mischief that are punishable at common law. 27-30. Also nuisances ; disturbing the peace; acts tenxding to defeat public justice. and various miscellaneous offences. 31, 32. Other instances named of common-law influence. 33-36. Brief review of the treatise; and 38. Conclusion. 1. IF a satisfactory conclusion has been reached in reference to the vexed question which has now been considered, and which has given rise to such strongly-conflicting opinions, by jurists of the highest eminence and ability, the remaining question, where, with one or two narrow exceptions, the eases and opinions are in VOL. XV.-21 (321) APPLICATION OF THE COMMON LAW almost perfect accord, cannot be attended with much difficulty. -

What's Reasonable?: Self-Defense and Mistake in Criminal and Tort

Do Not Delete 12/15/2010 10:20 PM WHAT’S REASONABLE?: SELF-DEFENSE AND MISTAKE IN CRIMINAL AND TORT LAW by Caroline Forell∗ In this Article, Professor Forell examines the criminal and tort mistake- as-to-self-defense doctrines. She uses the State v. Peairs criminal and Hattori v. Peairs tort mistaken self-defense cases to illustrate why application of the reasonable person standard to the same set of facts in two areas of law can lead to different outcomes. She also uses these cases to highlight how fundamentally different the perception of what is reasonable can be in different cultures. She then questions whether both criminal and tort law should continue to treat a reasonably mistaken belief that deadly force is necessary as justifiable self-defense. Based on the different purposes that tort and criminal law serve, Professor Forell explains why in self-defense cases criminal law should retain the reasonable mistake standard while tort law should move to a strict liability with comparative fault standard. I. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................... 1402 II. THE LAW OF SELF-DEFENSE ................................................... 1403 III. THE PEAIRS MISTAKE CASES .................................................. 1406 A. The Peairs Facts ..................................................................... 1408 B. The Criminal Case .................................................................. 1409 1. The Applicable Law ........................................................... 1409 -

Crimes Act 2016

REPUBLIC OF NAURU Crimes Act 2016 ______________________________ Act No. 18 of 2016 ______________________________ TABLE OF PROVISIONS PART 1 – PRELIMINARY ....................................................................................................... 1 1 Short title .................................................................................................... 1 2 Commencement ......................................................................................... 1 3 Application ................................................................................................. 1 4 Codification ................................................................................................ 1 5 Standard geographical jurisdiction ............................................................. 2 6 Extraterritorial jurisdiction—ship or aircraft outside Nauru ......................... 2 7 Extraterritorial jurisdiction—transnational crime ......................................... 4 PART 2 – INTERPRETATION ................................................................................................ 6 8 Definitions .................................................................................................. 6 9 Definition of consent ................................................................................ 13 PART 3 – PRINCIPLES OF CRIMINAL RESPONSIBILITY ................................................. 14 DIVISION 3.1 – PURPOSE AND APPLICATION ................................................................. 14 10 Purpose -

WALKER V. GEORGIA

Cite as: 555 U. S. ____ (2008) 1 THOMAS, J., concurring SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES ARTEMUS RICK WALKER v. GEORGIA ON PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA No. 08–5385. Decided October 20, 2008 JUSTICE THOMAS, concurring in the denial of the peti- tion of certiorari. Petitioner brutally murdered Lynwood Ray Gresham, and was sentenced to death for his crime. JUSTICE STEVENS objects to the proportionality review undertaken by the Georgia Supreme Court on direct review of peti- tioner’s capital sentence. The Georgia Supreme Court, however, afforded petitioner’s sentence precisely the same proportionality review endorsed by this Court in McCleskey v. Kemp, 481 U. S. 279 (1987); Pulley v. Harris, 465 U. S. 37 (1984); Zant v. Stephens, 462 U. S. 862 (1983); and Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U. S. 153 (1976), and described in Pulley as a “safeguard against arbitrary or capricious sentencing” additional to that which is constitu- tionally required, Pulley, supra, at 45. Because the Geor- gia Supreme Court made no error in applying its statuto- rily required proportionality review in this case, I concur in the denial of certiorari. In May 1999, petitioner recruited Gary Lee Griffin to help him “rob and kill a rich white man” and “take the money, take the jewels.” Pet. for Cert. 5 (internal quota- tion marks omitted); 282 Ga. 774, 774–775, 653 S. E. 2d 439, 443, (2007). Petitioner and Griffin packed two bicy- cles in a borrowed car, dressed in black, and took a knife and stun gun to Gresham’s house. -

Competing Theories of Blackmail: an Empirical Research Critique of Criminal Law Theory

Competing Theories of Blackmail: An Empirical Research Critique of Criminal Law Theory Paul H. Robinson,* Michael T. Cahill** & Daniel M. Bartels*** The crime of blackmail has risen to national media attention because of the David Letterman case, but this wonderfully curious offense has long been the favorite of clever criminal law theorists. It criminalizes the threat to do something that would not be criminal if one did it. There exists a rich liter- ature on the issue, with many prominent legal scholars offering their accounts. Each theorist has his own explanation as to why the blackmail offense exists. Most theories seek to justify the position that blackmail is a moral wrong and claim to offer an account that reflects widely shared moral intuitions. But the theories make widely varying assertions about what those shared intuitions are, while also lacking any evidence to support the assertions. This Article summarizes the results of an empirical study designed to test the competing theories of blackmail to see which best accords with pre- vailing sentiment. Using a variety of scenarios designed to isolate and test the various criteria different theorists have put forth as “the” key to blackmail, this study reveals which (if any) of the various theories of blackmail proposed to date truly reflects laypeople’s moral judgment. Blackmail is not only a common subject of scholarly theorizing but also a common object of criminal prohibition. Every American jurisdiction criminalizes blackmail, although there is considerable variation in its formulation. The Article reviews the American statutes and describes the three general approaches these provisions reflect. -

Dr Stephen Copp and Alison Cronin, 'The Failure of Criminal Law To

Dr Stephen Copp and Alison Cronin, ‘The Failure of Criminal Law to Control the Use of Off Balance Sheet Finance During the Banking Crisis’ (2015) 36 The Company Lawyer, Issue 4, 99, reproduced with permission of Thomson Reuters (Professional) UK Ltd. This extract is taken from the author’s original manuscript and has not been edited. The definitive, published, version of record is available here: http://login.westlaw.co.uk/maf/wluk/app/document?&srguid=i0ad8289e0000014eca3cbb3f02 6cd4c4&docguid=I83C7BE20C70F11E48380F725F1B325FB&hitguid=I83C7BE20C70F11 E48380F725F1B325FB&rank=1&spos=1&epos=1&td=25&crumb- action=append&context=6&resolvein=true THE FAILURE OF CRIMINAL LAW TO CONTROL THE USE OF OFF BALANCE SHEET FINANCE DURING THE BANKING CRISIS Dr Stephen Copp & Alison Cronin1 30th May 2014 Introduction A fundamental flaw at the heart of the corporate structure is the scope for fraud based on the provision of misinformation to investors, actual or potential. The scope for fraud arises because the separation of ownership and control in the company facilitates asymmetric information2 in two key circumstances: when a company seeks to raise capital from outside investors and when a company provides information to its owners for stewardship purposes.3 Corporate misinformation, such as the use of off balance sheet finance (OBSF), can distort the allocation of investment funding so that money gets attracted into less well performing enterprises (which may be highly geared and more risky, enhancing the risk of multiple failures). Insofar as it creates a market for lemons it risks damaging confidence in the stock markets themselves since the essence of a market for lemons is that bad drives out good from the market, since sellers of the good have less incentive to sell than sellers of the bad.4 The neo-classical model of perfect competition assumes that there will be perfect information. -

American Influence on Israel's Jurisprudence of Free Speech Pnina Lahav

Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly Volume 9 Article 2 Number 1 Fall 1981 1-1-1981 American Influence on Israel's Jurisprudence of Free Speech Pnina Lahav Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Pnina Lahav, American Influence on Israel's Jurisprudence of Free Speech, 9 Hastings Const. L.Q. 21 (1981). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly/vol9/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES American Influence on Israel's Jurisprudence of Free Speech By PNINA LAHAV* Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................ 23 Part 1: 1953-Enter Probable Danger ............................... 27 A. The Case of Kol-Ha'am: A Brief Summation .............. 27 B. The Recipient System on the Eve of Transplantation ....... 29 C. Justice Agranat: An Anatomy of Transplantation, Grand Style ...................................................... 34 D. Jurisprudence: Interest Balancing as the Correct Method to Define the Limitations on Speech .......................... 37 1. The Substantive Material Transplanted ................. 37 2. The Process of Transplantation -

Future Identities: Changing Identities in the UK – the Next 10 Years DR 19: Identity Related Crime in the UK David S

Future Identities: Changing identities in the UK – the next 10 years DR 19: Identity Related Crime in the UK David S. Wall Durham University January 2013 This review has been commissioned as part of the UK Government’s Foresight project, Future Identities: Changing identities in the UK – the next 10 years. The views expressed do not represent policy of any government or organisation DR19 Identity Related Crime in the UK Contents Identity Related Crime in the UK ............................................................................................................ 3 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 4 2. Identity Theft (theft of personal information) .................................................................................... 6 3. Creating a false identity ...................................................................................................................... 9 4. Committing Identity Fraud ................................................................................................................ 12 5. New forms of identity crime ............................................................................................................. 14 6. The law and identity crime................................................................................................................ 16 7. Conclusions ...................................................................................................................................... -

CRIMINAL ATTEMPTS at COMMON LAW Edwin R

[Vol. 102 CRIMINAL ATTEMPTS AT COMMON LAW Edwin R. Keedy t GENERAL PRINCIPLES Much has been written on the law of attempts to commit crimes 1 and much more will be written for this is one of the most interesting and difficult problems of the criminal law.2 In many discussions of criminal attempts decisions dealing with common law attempts, stat- utory attempts and aggravated assaults, such as assaults with intent to murder or to rob, are grouped indiscriminately. Since the defini- tions of statutory attempts frequently differ from the common law concepts,8 and since the meanings of assault differ widely,4 it is be- "Professor of Law Emeritus, University of Pennsylvania. 1. See Beale, Criminal Attempts, 16 HARv. L. REv. 491 (1903); Hoyles, The Essentials of Crime, 46 CAN. L.J. 393, 404 (1910) ; Cook, Act, Intention and Motive in the Criminal Law, 26 YALE L.J. 645 (1917) ; Sayre, Criminal Attempts, 41 HARv. L. REv. 821 (1928) ; Tulin, The Role of Penalties in the Criminal Law, 37 YALE L.J. 1048 (1928) ; Arnold, Criminal Attempts-The Rise and Fall of an Abstraction, 40 YALE L.J. 53 (1930); Curran, Criminal and Non-Criminal Attempts, 19 GEo. L.J. 185, 316 (1931); Strahorn, The Effect of Impossibility on Criminal Attempts, 78 U. OF PA. L. Rtv. 962 (1930); Derby, Criminal Attempt-A Discussion of Some New York Cases, 9 N.Y.U.L.Q. REv. 464 (1932); Turner, Attempts to Commit Crimes, 5 CA=. L.J. 230 (1934) ; Skilton, The Mental Element in a Criminal Attempt, 3 U. -

SECOND CONCURRENCE SCHALLER, J., Concurring

****************************************************** The ``officially released'' date that appears near the beginning of each opinion is the date the opinion will be published in the Connecticut Law Journal or the date it was released as a slip opinion. The operative date for the beginning of all time periods for filing postopinion motions and petitions for certification is the ``officially released'' date appearing in the opinion. In no event will any such motions be accepted before the ``officially released'' date. All opinions are subject to modification and technical correction prior to official publication in the Connecti- cut Reports and Connecticut Appellate Reports. In the event of discrepancies between the electronic version of an opinion and the print version appearing in the Connecticut Law Journal and subsequently in the Con- necticut Reports or Connecticut Appellate Reports, the latest print version is to be considered authoritative. The syllabus and procedural history accompanying the opinion as it appears on the Commission on Official Legal Publications Electronic Bulletin Board Service and in the Connecticut Law Journal and bound volumes of official reports are copyrighted by the Secretary of the State, State of Connecticut, and may not be repro- duced and distributed without the express written per- mission of the Commission on Official Legal Publications, Judicial Branch, State of Connecticut. ****************************************************** CONNECTICUT COALITION FOR JUSTICE IN EDUCATION FUNDING, INC. v. RELLÐSECOND -

Conflict of the Criminal Statute of Limitations with Lesser Offenses at Trial

William & Mary Law Review Volume 37 (1995-1996) Issue 1 Article 10 October 1995 Conflict of the Criminal Statute of Limitations with Lesser Offenses at Trial Alan L. Adlestein Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the Criminal Law Commons Repository Citation Alan L. Adlestein, Conflict of the Criminal Statute of Limitations with Lesser Offenses at Trial, 37 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 199 (1995), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol37/iss1/10 Copyright c 1995 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr CONFLICT OF THE CRIMINAL STATUTE OF LIMITATIONS WITH LESSER OFFENSES AT TRIAL ALAN L. ADLESTEIN I. INTRODUCTION ............................... 200 II. THE CRIMINAL STATUTE OF LIMITATIONS AND LESSER OFFENSES-DEVELOPMENT OF THE CONFLICT ........ 206 A. Prelude: The Problem of JurisdictionalLabels ..... 206 B. The JurisdictionalLabel and the CriminalStatute of Limitations ................ 207 C. The JurisdictionalLabel and the Lesser Offense .... 209 D. Challenges to the Jurisdictional Label-In re Winship, Keeble v. United States, and United States v. Wild ..................... 211 E. Lesser Offenses and the Supreme Court's Capital Cases- Beck v. Alabama, Spaziano v. Florida, and Schad v. Arizona ........................... 217 1. Beck v. Alabama-LegislativePreclusion of Lesser Offenses ................................ 217 2. Spaziano v. Florida-Does the Due Process Clause Require Waivability? ....................... 222 3. Schad v. Arizona-The Single Non-Capital Option ....................... 228 F. The Conflict Illustrated in the Federal Circuits and the States ....................... 230 1. The Conflict in the Federal Circuits ........... 232 2. The Conflict in the States .................. 234 III.