Economic Analysis of Threats and Their Illegality: Blackmail, Extortion, and Robbery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crimes Act 2016

REPUBLIC OF NAURU Crimes Act 2016 ______________________________ Act No. 18 of 2016 ______________________________ TABLE OF PROVISIONS PART 1 – PRELIMINARY ....................................................................................................... 1 1 Short title .................................................................................................... 1 2 Commencement ......................................................................................... 1 3 Application ................................................................................................. 1 4 Codification ................................................................................................ 1 5 Standard geographical jurisdiction ............................................................. 2 6 Extraterritorial jurisdiction—ship or aircraft outside Nauru ......................... 2 7 Extraterritorial jurisdiction—transnational crime ......................................... 4 PART 2 – INTERPRETATION ................................................................................................ 6 8 Definitions .................................................................................................. 6 9 Definition of consent ................................................................................ 13 PART 3 – PRINCIPLES OF CRIMINAL RESPONSIBILITY ................................................. 14 DIVISION 3.1 – PURPOSE AND APPLICATION ................................................................. 14 10 Purpose -

WALKER V. GEORGIA

Cite as: 555 U. S. ____ (2008) 1 THOMAS, J., concurring SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES ARTEMUS RICK WALKER v. GEORGIA ON PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA No. 08–5385. Decided October 20, 2008 JUSTICE THOMAS, concurring in the denial of the peti- tion of certiorari. Petitioner brutally murdered Lynwood Ray Gresham, and was sentenced to death for his crime. JUSTICE STEVENS objects to the proportionality review undertaken by the Georgia Supreme Court on direct review of peti- tioner’s capital sentence. The Georgia Supreme Court, however, afforded petitioner’s sentence precisely the same proportionality review endorsed by this Court in McCleskey v. Kemp, 481 U. S. 279 (1987); Pulley v. Harris, 465 U. S. 37 (1984); Zant v. Stephens, 462 U. S. 862 (1983); and Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U. S. 153 (1976), and described in Pulley as a “safeguard against arbitrary or capricious sentencing” additional to that which is constitu- tionally required, Pulley, supra, at 45. Because the Geor- gia Supreme Court made no error in applying its statuto- rily required proportionality review in this case, I concur in the denial of certiorari. In May 1999, petitioner recruited Gary Lee Griffin to help him “rob and kill a rich white man” and “take the money, take the jewels.” Pet. for Cert. 5 (internal quota- tion marks omitted); 282 Ga. 774, 774–775, 653 S. E. 2d 439, 443, (2007). Petitioner and Griffin packed two bicy- cles in a borrowed car, dressed in black, and took a knife and stun gun to Gresham’s house. -

Competing Theories of Blackmail: an Empirical Research Critique of Criminal Law Theory

Competing Theories of Blackmail: An Empirical Research Critique of Criminal Law Theory Paul H. Robinson,* Michael T. Cahill** & Daniel M. Bartels*** The crime of blackmail has risen to national media attention because of the David Letterman case, but this wonderfully curious offense has long been the favorite of clever criminal law theorists. It criminalizes the threat to do something that would not be criminal if one did it. There exists a rich liter- ature on the issue, with many prominent legal scholars offering their accounts. Each theorist has his own explanation as to why the blackmail offense exists. Most theories seek to justify the position that blackmail is a moral wrong and claim to offer an account that reflects widely shared moral intuitions. But the theories make widely varying assertions about what those shared intuitions are, while also lacking any evidence to support the assertions. This Article summarizes the results of an empirical study designed to test the competing theories of blackmail to see which best accords with pre- vailing sentiment. Using a variety of scenarios designed to isolate and test the various criteria different theorists have put forth as “the” key to blackmail, this study reveals which (if any) of the various theories of blackmail proposed to date truly reflects laypeople’s moral judgment. Blackmail is not only a common subject of scholarly theorizing but also a common object of criminal prohibition. Every American jurisdiction criminalizes blackmail, although there is considerable variation in its formulation. The Article reviews the American statutes and describes the three general approaches these provisions reflect. -

The Unnecessary Crime of Conspiracy

California Law Review VOL. 61 SEPTEMBER 1973 No. 5 The Unnecessary Crime of Conspiracy Phillip E. Johnson* The literature on the subject of criminal conspiracy reflects a sort of rough consensus. Conspiracy, it is generally said, is a necessary doctrine in some respects, but also one that is overbroad and invites abuse. Conspiracy has been thought to be necessary for one or both of two reasons. First, it is said that a separate offense of conspiracy is useful to supplement the generally restrictive law of attempts. Plot- ters who are arrested before they can carry out their dangerous schemes may be convicted of conspiracy even though they did not go far enough towards completion of their criminal plan to be guilty of attempt.' Second, conspiracy is said to be a vital legal weapon in the prosecu- tion of "organized crime," however defined.' As Mr. Justice Jackson put it, "the basic conspiracy principle has some place in modem crimi- nal law, because to unite, back of a criniinal purpose, the strength, op- Professor of Law, University of California, Berkeley. A.B., Harvard Uni- versity, 1961; J.D., University of Chicago, 1965. 1. The most cogent statement of this point is in Note, 14 U. OF TORONTO FACULTY OF LAW REv. 56, 61-62 (1956): "Since we are fettered by an unrealistic law of criminal attempts, overbalanced in favour of external acts, awaiting the lit match or the cocked and aimed pistol, the law of criminal conspiracy has been em- ployed to fill the gap." See also MODEL PENAL CODE § 5.03, Comment at 96-97 (Tent. -

CRIMINAL ATTEMPTS at COMMON LAW Edwin R

[Vol. 102 CRIMINAL ATTEMPTS AT COMMON LAW Edwin R. Keedy t GENERAL PRINCIPLES Much has been written on the law of attempts to commit crimes 1 and much more will be written for this is one of the most interesting and difficult problems of the criminal law.2 In many discussions of criminal attempts decisions dealing with common law attempts, stat- utory attempts and aggravated assaults, such as assaults with intent to murder or to rob, are grouped indiscriminately. Since the defini- tions of statutory attempts frequently differ from the common law concepts,8 and since the meanings of assault differ widely,4 it is be- "Professor of Law Emeritus, University of Pennsylvania. 1. See Beale, Criminal Attempts, 16 HARv. L. REv. 491 (1903); Hoyles, The Essentials of Crime, 46 CAN. L.J. 393, 404 (1910) ; Cook, Act, Intention and Motive in the Criminal Law, 26 YALE L.J. 645 (1917) ; Sayre, Criminal Attempts, 41 HARv. L. REv. 821 (1928) ; Tulin, The Role of Penalties in the Criminal Law, 37 YALE L.J. 1048 (1928) ; Arnold, Criminal Attempts-The Rise and Fall of an Abstraction, 40 YALE L.J. 53 (1930); Curran, Criminal and Non-Criminal Attempts, 19 GEo. L.J. 185, 316 (1931); Strahorn, The Effect of Impossibility on Criminal Attempts, 78 U. OF PA. L. Rtv. 962 (1930); Derby, Criminal Attempt-A Discussion of Some New York Cases, 9 N.Y.U.L.Q. REv. 464 (1932); Turner, Attempts to Commit Crimes, 5 CA=. L.J. 230 (1934) ; Skilton, The Mental Element in a Criminal Attempt, 3 U. -

Police Perjury: a Factorial Survey

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Police Perjury: A Factorial Survey Author(s): Michael Oliver Foley Document No.: 181241 Date Received: 04/14/2000 Award Number: 98-IJ-CX-0032 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. FINAL-FINAL TO NCJRS Police Perjury: A Factorial Survey h4ichael Oliver Foley A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Criminal Justice in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The City University of New York. 2000 This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. I... I... , ii 02000 Michael Oliver Foley All Rights Reserved This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. -

Group “A” Offenses Group “B” Offenses

Group “A” Offenses Group “B” Offenses Group B’s MUST have an arrest to be NIBRS Reportable NIBRS NIBRS NIBRS OFFENSES CODES NIBRS OFFENSES CODES NIBRS NIBRS Arson 200 Human Trafficking NIBRS OFFENSES CODES NIBRS OFFENSES CODES -Commercial Sex Acts 64A Assault Offenses -Involuntary Servitude 64B Bad Checks 90A Family Offenses, Non- 90F -Aggravated Assault 13A Violent -Simple Assault 13B Kidnapping/Abduction 100 -Intimidation 13C Curfew/Loitering/Vagrancy 90B Liquor Law Violations 90G Larceny/Theft Offenses Violations Bribery 510 -Pocket Picking 23A -Purse Snatching 23B Disorderly Conduct 90C Peeping Tom 90H Burglary/B&E 220 -Shoplifting 23C -Theft from Building 23D Driving Under the Influence 90D Trespassing 90J Counterfeiting/Forgery 250 -Theft from Coin-Operated Machine 23E or Device Drunkenness 90E All Other Offenses 90Z -Theft from Motor Vehicle 23F Destruction/Damage/Vandalism of 290 -Theft of Motor Vehicle Parts or 23G Property Accessories Source: Association of State Uniform Crime Reporting Programs (ASUCRP). Accessed on June 6, 2014. -All Other Larceny 23H Drug/Narcotic Offenses -Drug/Narcotic Violations 35A Motor Vehicle Theft 240 -Drug/Narcotic Equip. Violations 35B Pornography/Obscene Material 370 Embezzlement 270 Prostitution Offenses Extortion/Blackmail 210 -Prostitution 40A -Assisting or Promoting Prostitution 40B Fraud Offenses -Purchasing Prostitution 40C -False Pretenses/Swindle/ Confidence 26A Games -Credit Card/Automatic Teller Machine 26B Robbery 120 Fraud -Impersonation 26C -Welfare Fraud 26D Sex Offenses (Forcible) -Wire Fraud 26E -Forcible Rape 11A -Forcible Sodomy 11B -Sexual Assault with An Object 11C Gambling Offenses -Forcible Fondling 11D -Betting/Wagering 39A Sex Offenses (Non-Forcible) -Operating/Promoting/ Assisting 39B -Incest 36A Gambling -Gambling Equip. -

Penal Code Offenses by Punishment Range Office of the Attorney General 2

PENAL CODE BYOFFENSES PUNISHMENT RANGE Including Updates From the 85th Legislative Session REV 3/18 Table of Contents PUNISHMENT BY OFFENSE CLASSIFICATION ........................................................................... 2 PENALTIES FOR REPEAT AND HABITUAL OFFENDERS .......................................................... 4 EXCEPTIONAL SENTENCES ................................................................................................... 7 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 4 ................................................................................................. 8 INCHOATE OFFENSES ........................................................................................................... 8 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 5 ............................................................................................... 11 OFFENSES AGAINST THE PERSON ....................................................................................... 11 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 6 ............................................................................................... 18 OFFENSES AGAINST THE FAMILY ......................................................................................... 18 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 7 ............................................................................................... 20 OFFENSES AGAINST PROPERTY .......................................................................................... 20 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 8 .............................................................................................. -

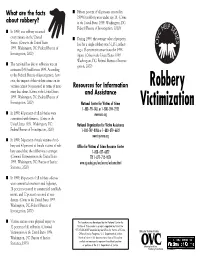

Robbery Victimization

What are the facts ■ Fifteen percent of all persons arrested in 1999 for robbery were under age 18. (Crime about robbery? in the United States 1999. Washington, DC: Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2000) ■ In 1999, one robbery occurred every minute in the United ■ During 1999, the average value of property States. (Crime in the United States loss for a single robbery was $1,131, reflect- 1999. Washington, DC: Federal Bureau of ing a 15-percent increase from the 1998 Investigation, 2000) figure. (Crime in the United States 1999. Washington, DC: Federal Bureau of Investi- ■ The national loss due to robberies was an gation, 2000) estimated $463 million in 1999. According to the Federal Bureau of Investigation, how- ever, the impact of this violent crime on its victims cannot be measured in terms of mon- Resources for Information Robbery etary loss alone. (Crime in the United States and Assistance 1999. Washington, DC: Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2000) National Center for Victims of Crime Victimization 1–800–FYI–CALL or 1–800–394–2255 ■ In 1999, 40 percent of all robberies were www.ncvc.org committed with firearms. (Crime in the United States 1999. Washington, DC: National Organization for Victim Assistance Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2000) 1–800–TRY–NOVA or 1–800–879–6682 www.try-nova.org ■ In 1999, 74 percent of male victims of rob- bery and 42 percent of female victims of rob- Office for Victims of Crime Resource Center bery stated that the robber was a stranger. 1–800–627–6872 (Criminal Victimization in the United States TTY 1–877–712–9279 1999. -

Conflict of the Criminal Statute of Limitations with Lesser Offenses at Trial

William & Mary Law Review Volume 37 (1995-1996) Issue 1 Article 10 October 1995 Conflict of the Criminal Statute of Limitations with Lesser Offenses at Trial Alan L. Adlestein Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the Criminal Law Commons Repository Citation Alan L. Adlestein, Conflict of the Criminal Statute of Limitations with Lesser Offenses at Trial, 37 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 199 (1995), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol37/iss1/10 Copyright c 1995 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr CONFLICT OF THE CRIMINAL STATUTE OF LIMITATIONS WITH LESSER OFFENSES AT TRIAL ALAN L. ADLESTEIN I. INTRODUCTION ............................... 200 II. THE CRIMINAL STATUTE OF LIMITATIONS AND LESSER OFFENSES-DEVELOPMENT OF THE CONFLICT ........ 206 A. Prelude: The Problem of JurisdictionalLabels ..... 206 B. The JurisdictionalLabel and the CriminalStatute of Limitations ................ 207 C. The JurisdictionalLabel and the Lesser Offense .... 209 D. Challenges to the Jurisdictional Label-In re Winship, Keeble v. United States, and United States v. Wild ..................... 211 E. Lesser Offenses and the Supreme Court's Capital Cases- Beck v. Alabama, Spaziano v. Florida, and Schad v. Arizona ........................... 217 1. Beck v. Alabama-LegislativePreclusion of Lesser Offenses ................................ 217 2. Spaziano v. Florida-Does the Due Process Clause Require Waivability? ....................... 222 3. Schad v. Arizona-The Single Non-Capital Option ....................... 228 F. The Conflict Illustrated in the Federal Circuits and the States ....................... 230 1. The Conflict in the Federal Circuits ........... 232 2. The Conflict in the States .................. 234 III. -

United States District Court District of Connecticut

Case 3:16-cr-00238-SRU Document 305 Filed 06/28/19 Page 1 of 49 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF CONNECTICUT UNITED STATES No. 3:16-cr-238 (SRU) v. FRANCISCO BETANCOURT, CARLOS ANTONIO HERNANDEZ, and LUCILO CABRERA RULING ON MOTIONS FOR JUDGMENT OF ACQUITTAL AND/OR FOR A NEW TRIAL (Doc. Nos. 234, 235, 242, 257) Francisco Betancourt, Carlos Hernandez, and Lucilo Cabrera were charged via a third superseding indictment with kidnapping, conspiracy to commit kidnapping, extortion, and conspiracy to commit extortion.1 See Third Super. Indict., Doc. No. 115. After a nine-day trial, the jury returned its verdict on March 9, 2018. See Verdict, Doc. No. 225. Betancourt, Hernandez, and Cabrera were each found guilty of one count of conspiracy to commit kidnapping (Count One) and one count of conspiracy to commit extortion (Count Two). Id. In addition, Betancourt was convicted of three counts of kidnapping (Counts Three, Four, and Five), and three counts of extortion (Counts Six, Nine, and Eleven).2 Id. Hernandez was convicted of three counts of kidnapping (Counts Three, Four, and Five), and two counts of extortion (Counts Six and Nine).3 Cabrera was convicted of two counts of kidnapping (Counts 1 Co-defendant Pascual Rodriguez was also charged in the third superseding indictment. See Third Super. Indict., Doc. No. 115. Rodriguez filed a Motion to Sever before trial, which I granted. See Order, Doc. No. 181. Accordingly, he was not tried alongside Betancourt, Hernandez, and Cabrera and later entered a guilty plea on October 12, 2018. See Findings and Recommendations, Doc. -

Supreme Court of the United States ______

No. 19-373 __________________________________________________ IN THE Supreme Court of the United States ________________ JAMES WALKER, Petitioner, v. UNITED STATES, Respondent. ________________ On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit ________________ MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE AMICUS CURIAE BRIEF AND BRIEF OF NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR PUBLIC DEFENSE AS AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER ________________ EMILY HUGHES DANIEL T. HANSMEIER Co-Chair Amicus Counsel of Record Committee 500 State Avenue NATIONAL ASSOCIATION Suite 201 FOR PUBLIC DEFENSE Kansas City, KS 66101 474 Boyd Law Building (913) 551-6712 University of Iowa [email protected] College of Law Iowa City, IA 52242 Counsel for Amicus Curiae ________________________________________________ MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AS AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER Pursuant to Supreme Court Rules 21, 24, 33.1, and 37(b), the National Association for Public Defense (NAPD) moves this Court for leave to file the attached amicus brief in support of petitioners. The NAPD is an association of more than 14,000 professionals who deliver the right to counsel throughout all U.S. states and territories. NAPD members include attorneys, investigators, social workers, administrators, and other support staff who are responsible for executing the constitutional right to effective assistance of counsel, including regularly researching and providing advice to indigent clients in state and federal criminal cases. NAPD’s members are the advocates in jails, in courtrooms, and in communities and are experts in not only theoretical best practices, but also in the practical, day-to-day delivery of indigent defense representation. Their collective expertise represents state, county, and federal systems through full-time, contract, and assigned counsel delivery mechanisms, dedicated juvenile, capital and appellate offices, and through a diversity of traditional and holistic practice models.