Phenomenological Alma Mater Borders of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regional Climate Studies Series Editors: H.-J. Bolle, M. Menenti, I

Regional Climate Studies Series Editors: H.-J. Bolle, M. Menenti, I. Rasool The BACC Author Team Assessment of Climate Change for the Baltic Sea Basin 123 The BACC Author Team The International BALTEX Secretariat GKSS-Forschungszentrum Geesthacht GmbH Max-Planck-Str. 1 D-21502 Geesthacht Germany [email protected] ISBN: 978-3-540-72785-9 e-ISBN: 978-3-540-72786-6 Regional Climate Studies ISSN: pending Library of Congress Control Number: 2007938497 c 2008 Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilm or in any other way, and storage in data banks. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the German Copyright Law of September 9, 1965, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer. Violations are liable to prosecution under the German Copyright Law. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. Cover design: deblik, Berlin Printed on acid-free paper 987654321 springer.com Preface Climate change and its impact on our life, our en- Global Energy and Water Cycle Experiment vironment and ecosystems in general, are in these (GEWEX) of the World Climate Research Pro- days at the forefront of public concern and polit- gram (WCRP). -

Tartu Kuvand Reisisihtkohana Kohalike Ja Välismaiste Turismiekspertide Seas

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DSpace at Tartu University Library Tartu Ülikool Sotsiaalteaduskond Ajakirjanduse ja kommunikatsiooni instituut Tartu kuvand reisisihtkohana kohalike ja välismaiste turismiekspertide seas Bakalaureusetöö (4 AP) Autor: Maarja Ojamaa Juhendaja: Margit Keller, PhD Tartu 2009 Sisukord Sissejuhatus ..................................................................................................................................... 5 1. Töö teoreetilised ja empiirilised lähtekohad ............................................................................ 7 1.1. Turism .................................................................................................................................. 7 1.2. Reisisihtkoha maine ja selle tekkimine ............................................................................ 9 1.2.1. Võimalikud takistused positiivse maine kujunemisel ............................................. 11 1.3. Sihtkoha bränd ja brändimine ........................................................................................ 12 1.4. Teised uuringud sarnastel teemadel ............................................................................... 15 1.5. Uuringu objekt: Tartu reisisihtkohana ............................................................................ 16 1.5.1. Turismistatistika Eestis ja Tartus ............................................................................ 17 2. Uurimisküsimused ................................................................................................................ -

Soviet Housing Construction in Tartu: the Era of Mass Construction (1960 - 1991)

University of Tartu Faculty of Science and Technology Institute of Ecology and Earth Sciences Department of Geography Master thesis in human geography Soviet Housing Construction in Tartu: The Era of Mass Construction (1960 - 1991) Sille Sommer Supervisors: Michael Gentile, PhD Kadri Leetmaa, PhD Kaitsmisele lubatud: Juhendaja: /allkiri, kuupäev/ Juhendaja: /allkiri, kuupäev/ Osakonna juhataja: /allkiri, kuupäev/ Tartu 2012 Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Literature review ................................................................................................................................. 5 Housing development in the socialist states .................................................................................... 5 From World War I until the 1950s .............................................................................................. 5 From the 1950s until the collapse of the Soviet Union ............................................................... 6 Socio-economic differentiations in the socialist residential areas ................................................... 8 Different types of housing ......................................................................................................... 11 The housing estates in the socialist city .................................................................................... 13 Industrial control and priority sectors .......................................................................................... -

224 Volli Kalm

VOLLI KALM (10.02.1953–23.12.2017) In memoriam Rector Professor Volli Kalm Volli Kalm was born at Aluste near Vändra on 10 February 1953. He graduated from the Vändra Secondary School in 1971 and from the Geology speciality of the University of Tartu in 1976. He was a doctoral student of the Institute of Geology of the Estonian Academy of Sciences in 1980–1984 and had his post-doctoral studies at the Alberta University in Canada in 1988–1989. He was a lecturer of the University of Tartu since 1986, then a docent and Head of the Institute of Geology and Dean of the Faculty of Biology and Geography. Volli Kalm was elected as professor in 1992 and was the Vice- Rector for Academic Affairs in 1998–2003 and Rector from 2012. On 1 July 2017, Professor Volli Kalm was re-elected for his second term of office as the head of the University of Tartu and remained the rector until his death. His main research orientations were paleoclimate, paleogeography and chronology of continental glaciations, sedimentology, i.e. research into rock weathering and formation of sedimentary rock, geoarcheology. In 2005 he was awarded the Order of Merit of the White Star – 4th Class. Volli Kalm regarded international cooperation and visibility of the university as very important. In 2016 the University of Tartu became a member of the network of research- intensive universities, The Guild, and Volli Kalm was also elected as a member of its board in 2017. In November 2017, Volli Kalm was elected as the Honorary Doctor of the Tbilisi State University. -

Estonian Academy of Sciences Yearbook 2018 XXIV

Facta non solum verba ESTONIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES YEARBOOK FACTS AND FIGURES ANNALES ACADEMIAE SCIENTIARUM ESTONICAE XXIV (51) 2018 TALLINN 2019 This book was compiled by: Jaak Järv (editor-in-chief) Editorial team: Siiri Jakobson, Ebe Pilt, Marika Pärn, Tiina Rahkama, Ülle Raud, Ülle Sirk Translator: Kaija Viitpoom Layout: Erje Hakman Photos: Annika Haas p. 30, 31, 48, Reti Kokk p. 12, 41, 42, 45, 46, 47, 49, 52, 53, Janis Salins p. 33. The rest of the photos are from the archive of the Academy. Thanks to all authos for their contributions: Jaak Aaviksoo, Agnes Aljas, Madis Arukask, Villem Aruoja, Toomas Asser, Jüri Engelbrecht, Arvi Hamburg, Sirje Helme, Marin Jänes, Jelena Kallas, Marko Kass, Meelis Kitsing, Mati Koppel, Kerri Kotta, Urmas Kõljalg, Jakob Kübarsepp, Maris Laan, Marju Luts-Sootak, Märt Läänemets, Olga Mazina, Killu Mei, Andres Metspalu, Leo Mõtus, Peeter Müürsepp, Ülo Niine, Jüri Plado, Katre Pärn, Anu Reinart, Kaido Reivelt, Andrus Ristkok, Ave Soeorg, Tarmo Soomere, Külliki Steinberg, Evelin Tamm, Urmas Tartes, Jaana Tõnisson, Marja Unt, Tiit Vaasma, Rein Vaikmäe, Urmas Varblane, Eero Vasar Printed in Priting House Paar ISSN 1406-1503 (printed version) © EESTI TEADUSTE AKADEEMIA ISSN 2674-2446 (web version) CONTENTS FOREWORD ...........................................................................................................................................5 CHRONICLE 2018 ..................................................................................................................................7 MEMBERSHIP -

EESTI MAAÜLIKOOL Katri Vene KIIRABIKUTSETE JAOTUVUS

EESTI MAAÜLIKOOL Põllumajandus- ja keskkonnainstituut Katri Vene KIIRABIKUTSETE JAOTUVUS ELANIKKONNA RISKIRÜHMADE ALUSEL TARTU LINNAS KUUMALAINETE JA KUUMAPÄEVADE AJAL DIVISION OF AMBULANCE CALLS ON THE BASIS OF POPULATION RISK GROUPS IN TARTU CITY DURING HEAT WAVES AND HOT DAYS Magistritöö Linna- tööstusmaastike korralduse õppekava Juhendaja: prof. Kalev Sepp, PhD Tartu, 2017 Eesti Maaülikool Kreutzwaldi 1, Tartu 51014 Magistritöö lühikokkuvõte Autor: Katri Vene Õppekava: Linna- ja tööstusmaastike korraldus Pealkiri: Kiirabikutsete jaotuvus elanikkonna riskirühmade alusel Tartu linnas kuumalainete ja kuumapäevade ajal Lehekülgi: 78 Jooniseid: 27 Tabeleid: 3 Lisasid: 4 Osakond: Põllumajandus- ja keskkonnainstituut Uurimisvaldkond (ja mag. töö puhul valdkonna kood): Linna ja maa planeerimine (S240) Juhendaja(d): prof. Kalev Sepp Kaitsmiskoht ja -aasta: Tartu, 2017 Kuumalained on looduslikest ohtudest üks tähelepanuväärsemaid, kuid vaatamata tõsistele tagajärgedele pööratakse neile siiski vähe tähelepanu. Kuumalaine avaldab ühiskonnale märkimisväärset mõju suurendades muuhulgas ka suremuse riski. Uurimistöö eesmärgiks on tuvastada kuumalainete ja kuumapäevade esinemised Tartu linnas ning hinnata kiirabi väljakutsete sagedust, iseloomu ja paiknemist linnaruumis elanikkonna riskirühmade alusel antud perioodidel. Uurimistöös kasutatakse materjali saamisel kahte andmebaasi- Tartu Observatooriumi õhutemperatuuride jaotuvustabelit ning KIIRA andmebaasi. Maakatte tüüpide analüüsimiseks on kasutatud Maa- ameti Eesti topograafia andmekogu põhikaarti -

1 Estonian University of Life Sciences Kreutzwaldi 1

ESTONIAN LANGUAGE AND CULTURE COURSE (ESTILC) 2018/2019 ORGANISING INSTITUTION ’S INFORMATION FORM NAME OF THE INSTITUTION : ESTONIAN UNIVERSITY OF LIFE SCIENCES ADDRESS : KREUTZWALDI 1, TARTU COUNTRY : ESTONIA ESTILC LANGUAGE LEVEL COURSES ORGANISED: LEVEL I (BEGINNER ) X LEVEL II (INTERMEDIATE ) NUMBER OF COURSES : 1 NUMBER OF COURSES : DATES : 08.08-24.08.2018 DATES : WEB SITE HTTPS :// WWW .EMU .EE /EN /ADMISSION S/EXCHANGE -STUDIES /ERASMUS / PLEASE NOTE THAT ALL STUDENT APPLICATIONS FOR OUR ESTILC COURSE SHOULD BE SENT BY E -MAIL TO THE FOLLOWING ADDRESS : APPLICATION DEADLINE 31.05.2018 STAFF JOB TITLE / NAME ADDRESS , TELEPHONE , FAX , E-MAIL CONTACT PERSON ESTONIAN UNIVERSITY OF LIFE SCIENCES FOR ESTILC KREUTZWALDI 56/1, 51014 TARTU /E STONIA LIISI VESKE PHONE : +372 731 3174 JOB TITLE FAX : +372 731 3037 PROGRAMME COORDINATOR E-MAIL : LIISI .V ESKE @EMU .EE ESTONIAN UNIVERSITY OF LIFE SCIENCES KREUTZWALDI 56/1, 51014 TARTU /E STONIA RESPONSIBLE PERSON FOR THE PROGRAMME PHONE : +372 731 3174 FAX : +372 731 3037 LIISI VESKE E-MAIL : LIISI .V ESKE @EMU .EE PART I: GENERAL INFORMATION • DESCRIPTION OF TOWN - SHORT HISTORY AND LOCATION 1 Tartu is the second largest city of Estonia. Tartu is located 185 kilometres to south from the capital Tallinn. Tartu is known also as the centre of Southern Estonia. The Emajõgi River, which connects the two largest lakes (Võrtsjärv and Peipsi) of Estonia, flows for the length of 10 kilometres within the city limits and adds colour to the city. As Tartu has been under control of various rulers throughout its history, there are various names for the city in different languages. -

Mitte-Tartutu

MitteMitte-Tarttuu Mitte-Tartu Mitte-Tartu TOPOFON Koostanud ja toimetanud Sven Vabar Kujundanud Mari Ainso Pildistanud Kaja Pae Mitte-Tartu tänab: Eesti Kultuurkapitali, Tartu Kultuurkapitali, kirjandusfestivali Prima Vista ja Eesti Kirjanike Liidu Tartu osakonda © Autorid Topofon, 2012 Tartu ISBN 978-9949-30-404-2 Trükkinud AS Ecoprint Sisukord Sven Vabar Eessõna 6 Anti Saar Ernst 16 Berk Vaher Baltijos Cirkas 28 Joanna Ellmann maa-alused väljad 38 Maarja Pärtna 48 Kaja Pae 10π 58 Aare Pilv Servad 74 Tanel Rander Odessa või São Paulo? 90 Meelis Friedenthal Kass 100 Lauri Pilter Rälby ja Tarby 114 c: Teekond põllule 132 Erkki Luuk NÕIUTUD X 142 Tanel Rander Jõgi ja jõerahvas 156 Kiwa t-st 168 Mehis Heinsaar Kuusteist vaikuse aastat 190 Sven Vabar Tartu kaks lagendikku 200 Sven Vabar Tänavakunstnikud 212 Jaak Tomberg Faddei Bulgarini kümme soont 234 andreas w blade runner : jooksja mõõgateral 288 Mehis Heinsaar Ta on valmis ja ootel 302 5 Sven Vabar Eessõna Werneri kohvik, kevad/sügis-hooajaline Toomemägi, kirjanduslik Kar- lova, Supilinn oma aguliromantikaga. Neist kohtadest käesolevas raa- matus juttu ei tule. See kõik on Tartu. Mitte-Tartu on mujal. Hiinalinn oma hämara, postmilitaristliku elanikkonnaga ja määratu garaaživo- hanguga sealsamas kõrval. Raadi lennuväli. Annelinn. Aardla-kandi tühermaad ja Võru maantee äärsed põllupealsed uusarendused. Luhad. Ühe Turu tänava autopesula külge ehitatud igavikuline hamburgeri- putka, kus on tunda Jumala ligiolekut. Küütri tänava metroopeatus. Emajõgi küll, aga pigem jõepõhja muda ühes kõige seal leiduvaga. Supilinn küll, aga üks hoopis teistsugune Supilinn. Tõsi, piir Tartu ja Mitte-Tartu vahel on kohati hämar ja hägune nagu Mitte-Tartu isegi. Humanitaarteadustes tähistab „mitte-koht“ tavaliselt prantsuse antropoloogi Marc Augé poolt kasutusele võetud terminit. -

Estonia for the WMO/UNEP Ozone Research Managers Meeting, 02 - 04 May 2011, Geneva, Switzerland

Report of Ongoing and Planned Ozone and Ultraviolet Radiation Activities in Estonia for the WMO/UNEP Ozone Research Managers Meeting, 02 - 04 May 2011, Geneva, Switzerland By Kalju Eerme, Tartu Observatory 1. OBSERVATIONAL ACTIVITIES Most of systematic monitoring of atmospheric ozone and UV solar radiation in Estonia is performed at Tõravere (58° 15' N, 26° 28' E, 70 m a. s. l.), where the research institute Tartu Observatory and the Tartu-Tõravere Meteorological Station of the Estonian Meteorological and Hydrological Institute (EMHI) are located. Research areas of the Tartu Observatory are astrophysics and atmospheric physics. The meteorological station belongs to the Baseline Surface Radiation Network (BSRN) and is specialized on solar radiation measurements. Scientific work on ozone and UV radiation is performed since early 1990s at the department of atmospheric physics of Tartu Observatory. Different auxiliary regular measuremants like aerosol and cloud data collection are also performed at the same location. Since 2002 sun photometer of NASA AERONET measuring column aerosol optical depth (AOD) operates there and the group of aerosol studies of University of Tartu performs atmospheric aerosol size distribution measurements. The landscape pattern around consits of arable fields, grassland areas and patches of coniferous forest. It may be considered typical to Estonia. 1.1 Measurements of column ozone Most of research work using column ozone is based on satellite data. Local column ozone measurements at Tõravere have been rather episodic. Regular direct sun column ozone measurements have been carried out in 1994-1999 using specially suited laboratory spectrometer SDL-1 supplied with a mirror system and Dobson retrieval algorithm. -

Programme Handbook 1

Tartu, Estonia 8 - 10 August 2017 Programme handbook 1 Contents Programme ............................................................................................................................................. 2 Abstracts ................................................................................................................................................. 6 Invited speakers .................................................................................................................................. 6 Participants ....................................................................................................................................... 17 Practical information ............................................................................................................................ 38 Directions .............................................................................................................................................. 44 Contacts of local organizers .................................................................................................................. 46 Maps of Tartu ........................................................................................................................................ 47 Programme Monday, August 7th 16:00 – 20:00 Registration of participants Estonian Biocentre, Riia 23b 20:00 – 22:00 Welcome reception & BBQ Vilde Ja Vine restaurant, Vallikraavi 4 Tuesday, August 8th 08:45 – 09:35 Registration of participants Estonian Biocentre, Riia 23b 9:35 -

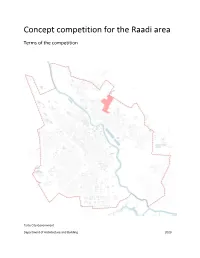

Concept Competition for the Raadi Area

Concept competition for the Raadi area Terms of the competition Tartu City Government Department of Architecture and Building 2020 Table of contents 1. Objective, competition area and contact area of the concept competition .......................................................... 3 2. History .................................................................................................................................................................... 5 3. Detailed plans and architectural plans in effect for the area ................................................................................. 7 4. Streets of the competition area ........................................................................................................................... 11 5. Environment and landscaping .............................................................................................................................. 12 6. Competition task by properties ........................................................................................................................... 13 7. Organisation of the competition .......................................................................................................................... 17 7.1 Organiser of the competition ........................................................................................................................ 17 7.2 Competition format ...................................................................................................................................... -

Downloads/Newsletters/SIEF-Spring-2020.Pdf?Utm Source=Newsletter&Utm Medium=Sendy&Utm Newsletter=SIEF Autumn2019, Last Accessed on 21.09.2020

THE YEARBOOK OF BALKAN AND BALTIC STUDIES VOLUME 3 INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY OF BALKAN AND BALTIC STUDIES THE YEARBOOK OF BALKAN AND BALTIC STUDIES VOLUME 3 TRACKING THE RITUAL YEAR ON THE MOVE IN DIFFERENT CULTURAL SETTINGS AND SYSTEMS OF VALUES editor-in-chief EKATERINA ANASTASOVA guest editors IRINA SEDAKOVA LAURENT SÉBASTIEN FOURNIER ELM SCHOLARLY PRESS VILNIUS-TARTU-SOFIA-RIGA 2020 Editor-in-chief: Ekaterina Anastasova Guest editors: Irina Sedakova, Institute of Slavic Studies, Moscow & Laurent Sébastien Fournier, Aix-Marseille-University, France Editors: Mare Kõiva, Inese Runce, Žilvytis Šaknys Cover: Lina Gergova Layout: Diana Kahre Editorial board: Nevena Škrbić Alempijević (Croatia), Jurji Fikfak (Slovenia), Evangelos Karamanes (Greece), Zoja Karanović (Serbia), Solveiga Krumina-Konkova (Latvia), Andres Kuperjanov (Estonia), Thede Kahl (Germany), Ermis Lafazanovski (North Macedonia), Tatiana Minniyakhmetova (Austria), Alexander Novik (Russia), Rasa Paukštytė-Šaknienė (Lithuania), Irina Sedakova (Russia), Irina Stahl (Romania), Svetoslava Toncheva (Bulgaria), Piret Voolaid (Estonia) Supported by Bulgarian, Lithuanian, Estonian and Latvian Academies of Sciences, Centre of Excellence in Estonian Studies; Institute of Ethnology and Folklore Studies with Ethnographic Museum, Estonian Literary Museum, Lithuanian Institute of History, Institute of Philosophy and Sociology, University of Latvia © 2020 by the authors © International Society of Balkan and Baltic Studies © Estonian Literary Museum ISSN 2613-7844 (printed) ISSN 2613-7852 (pdf)