The Perceivable Landscape a Theoretical-Methodological Approach to Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abstract Evaluating Holocene Precipitation

ABSTRACT EVALUATING HOLOCENE PRECIPITATION VARIABILITY IN THE BALTIC REGION USING OXYGEN ISOTOPES OF LACUSTRINE CARBONATE FROM ESTONIA Carolyn Fortney, M.S. Department of Geology and Environmental Geosciences Northern Illinois University, 2016 Nathan D. Stansell, Director Oxygen isotopes derived from authigenic carbonate from open lake systems record variations in seasonal precipitation source. This study focuses on the sediment record from Lake Nuudsaku in southern Estonia to evaluate how winter versus summer precipitation has changed throughout the Holocene as a result of fluctuating North Atlantic Ocean conditions, primarily the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO). Estonia receives precipitation with a lower δ18O value from the North Atlantic and Baltic Sea during the winter months. In contrast, during the summer months Estonia receives precipitation with greater δ18O values from warmer North Atlantic waters and from the Mediterranean Sea and Black Sea. Therefore, lower δ18O values in the carbonate record were interpreted as periods of time in which there were increases in the amount of winter precipitation. Oxygen isotope data indicate relatively wet winters during the early Holocene (9960 to 8800 cal yr BP) followed by a shift toward drier winters during the middle of the Holocene (8800 to 4200 cal yr BP). The late Holocene (4200 cal yr BP to the present) was characterized by the wettest winters recorded in the oxygen isotope record. The periods of increased winter precipitation in the Baltic region generally coincided with periods of increased NAO index between 5200 cal yr BP and 1000 cal yr BP. There was an inverse relationship between winter precipitation and NAO index during the Medieval Climate Anomaly and the Little Ice Age (900 to 100 cal yr BP). -

Võnnu Valla Arengukava Aastateks 2012-2022

LISA Võnnu Vallavolikogu 27.10.2011 määruse nr 15 juurde VÕNNU VALLA ARENGUKAVA AASTATEKS 2012-2022 Muudetud Võnnu Vallavolikogu 13.juuni 2013.a määrusega nr 5 Võnnu Vallavalitsus VÕNNU VALLA ARENGUKAVA AASTATEKS 2012 – 2022 Sisukord Eessõna ...................................................................................................................................... 4 I OSA. Minevik ja olevik .............................................................................................................. 5 1. Üldinformatsioon ........................................................................................................................... 5 2. Valla areng aastatel 2009 kuni 2011 ................................................................................................ 9 2.1 Vald kui haldusüksus. ............................................................................................................................................ 9 2.1.2 Valla eelarve ja selle dünaamika. ................................................................................................................... 9 2.1.3 Rahvastik ...................................................................................................................................................... 13 2.2 Elukeskkond ........................................................................................................................................................ 16 2.2.1 Looduskeskkond ja puhkealad .................................................................................................................... -

38. Hummuli Pargijooks Finiš Üldarvestus

38. Hummuli pargijooks Finiš üldarvestus ILM: KOH Nr Nimi Sünni Vank Koht Klubi Elukoht Aeg Tillujooks 150m 1. 213 Richard Rohelpuu 2015 P6 1. Põlva 0:00:24,5 2. 230 Kimbra Sööt 2015 T6 1. SK Augur Tallinn 0:00:25,1 3. 232 Johanna Uibo 2015 T6 2. Otepää 0:00:26,0 4. 281 Frank Hansmann 2016 P6 2. Viljandi 0:00:26,1 5. 226 Nora Ojaste 2015 T6 3. Karupesa Team Otepää/Tartu 0:00:26,3 6. 231 Marjanne Tammekivi 2016 T6 4. MTÜ Karupesa Otepää 0:00:27,2 7. 224 Delisa -Laurell Loos 2015 T6 5. Hummuli 0:00:27,7 8. 214 Herman Varik 2016 P6 3. Ainja küla Mulgi vald 0:00:28,6 9. 227 Emma Pisartšik 2015 T6 6. Tõrva 0:00:28,9 10. 272 Aniita Almre 2015 T6 7. Tõrva vald 0:00:29,0 11. 223 Selena Kikkas 2015 T6 8. Valga 0:00:30,8 12. 210 Ralf Julius Korts 2015 P6 4. Tõrva vald 0:00:31,4 13. 212 Karel Pirnipuu 2016 P6 5. Karupesa Team Valgamaa 0:00:32,3 14. 209 Ranet Koor 2016 P6 6. Võru 0:00:32,3 15. 277 Armin Veemees 2016 P6 7. Helenurme 0:00:33,1 16. 280 Mona Ruubel 2016 T6 9. Tallinn 0:00:33,4 17. 233 Cenna Uibopuu 2016 T6 10. Valga 0:00:33,4 18. 200 Ken Kirt 2017 P4 1. Tõrva 0:00:35,2 19. 234 Aurelia Vare 2016 T6 11. Tsirguliina 0:00:36,0 20. -

Alevist Vallamajani from Borough to Community House

Eesti Vabaõhumuuseumi Toimetised 2 Alevist vallamajani Artikleid maaehitistest ja -kultuurist From borough to community house Articles on rural architecture and culture Tallinn 2010 Raamatu väljaandmist on toetanud Eesti Kultuurkapital. Toimetanud/ Edited by: Heiki Pärdi, Elo Lutsepp, Maris Jõks Tõlge inglise keelde/ English translation: Tiina Mällo Kujundus ja makett/ Graphic design: Irina Tammis Trükitud/ Printed by: AS Aktaprint ISBN 978-9985-9819-3-1 ISSN-L 1736-8979 ISSN 1736-8979 Sisukord / Contents Eessõna 7 Foreword 9 Hanno Talving Hanno Talving Ülevaade Eesti vallamajadest 11 Survey of Estonian community houses 45 Heiki Pärdi Heiki Pärdi Maa ja linna vahepeal I 51 Between country and town I 80 Marju Kõivupuu Marju Kõivupuu Omad ja võõrad koduaias 83 Indigenous and alien in home garden 113 Elvi Nassar Elvi Nassar Setu küla kontrolljoone taga – Lõkova Lykova – Setu village behind the 115 control line 149 Elo Lutsepp Elo Lutsepp Asustuse kujunemine ja Evolution of settlement and persisting ehitustraditsioonide püsimine building traditions in Peipsiääre Peipsiääre vallas. Varnja küla 153 commune. Varnja village 179 Kadi Karine Kadi Karine Miljööväärtuslike Virumaa Milieu-valuable costal villages of rannakülade Eisma ja Andi väärtuste Virumaa – Eisma and Andi: definition määratlemine ja kaitse 183 of values and protection 194 Joosep Metslang Joosep Metslang Palkarhitektuuri taastamisest 2008. Methods for the preservation of log aasta uuringute põhjal 197 architecture based on the studies of 2008 222 7 Eessõna Eesti Vabaõhumuuseumi toimetiste teine köide sisaldab 2008. aasta teaduspäeva ettekannete põhjal kirjutatud üpris eriilmelisi kirjutisi. Omavahel ühendab neid ainult kaks põhiteemat: • maaehitised ja maakultuur. Hanno Talvingu artikkel annab rohkele arhiivimaterjalile ja välitööaine- sele toetuva esmase ülevaate meie valdade ja vallamajade kujunemisest alates 1860. -

Üldplaneeringu Keskkonnamõju Stratee Giline Hindamine

Ülenurme valla üldplaneeringu keskkonnamõju stratee giline hindamine ÜLENURME VALLA ÜLDPLANEERINGU KESKKONNAMÕJU STRATEEGILISE HINDAMISE ARUANNE KMH ekspert: Olavi Hiiemäe Litsents: KMH0101 [email protected] Tartu 2008 Koostaja: KMH ekspert Olavi Hiiemäe Ülenurme valla üldplaneeringu keskkonnamõju stratee giline hindamine SISUKORD ARUANDE SISU KOKKUVÕTE ............................ ......................................................... 4 1. SISSEJUHATUS ........................................................................................................ 6 1.1. Keskkonnamõju strateegilise hindamise objekt ...... ............................................ 6 1.2. Strateegilise planeerimisdokumendi eesmärk ........ ............................................. 6 1.3. Strateegilise keskkonnamõju hindamise osapooled ... ......................................... 7 2. PLANEERINGUALA KIRJELDUS .......................................................................... 9 2.1. Ülenurme valla üldiseloomustus .................... ..................................................... 9 2.2. Ettevõtluskeskkond ................................ ........................................................... 10 2.3. Sotsiaalne keskkond .......................................................................................... 11 2.4. Infrastruktuur .................................................................................................... 11 3. PIIRANGUID PÕHJUSTAVAD OBJEKTID ................... ...................................... 13 3.1. -

Soviet Housing Construction in Tartu: the Era of Mass Construction (1960 - 1991)

University of Tartu Faculty of Science and Technology Institute of Ecology and Earth Sciences Department of Geography Master thesis in human geography Soviet Housing Construction in Tartu: The Era of Mass Construction (1960 - 1991) Sille Sommer Supervisors: Michael Gentile, PhD Kadri Leetmaa, PhD Kaitsmisele lubatud: Juhendaja: /allkiri, kuupäev/ Juhendaja: /allkiri, kuupäev/ Osakonna juhataja: /allkiri, kuupäev/ Tartu 2012 Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Literature review ................................................................................................................................. 5 Housing development in the socialist states .................................................................................... 5 From World War I until the 1950s .............................................................................................. 5 From the 1950s until the collapse of the Soviet Union ............................................................... 6 Socio-economic differentiations in the socialist residential areas ................................................... 8 Different types of housing ......................................................................................................... 11 The housing estates in the socialist city .................................................................................... 13 Industrial control and priority sectors .......................................................................................... -

1. Sissejuhatus 5

Hummuli valla ühisveevärgi ja –kanalisatsiooni arendamise kava aastateks 2009-2019 1. SISSEJUHATUS 5 2. SISUKOKKUVÕTE 6 2.1 Sotsiaal-majanduslik ülevaade........................................................................... 6 2.2 Olemasolev veevarustussüsteem ...................................................................... 6 2.3 Perspektiivne veetarbimine aastal 2018............................................................. 9 2.4 Veevarustuse tehnilised indikaatorid................................................................ 10 2.5 Olemasolev kanalisatsioonisüsteem ................................................................ 10 2.6 Reovee vooluhulgad ja reostuskoorumused .................................................... 11 2.6.1 Reovee keskmised vooluhulgad ...................................................................... 11 2.7 Hinnang olemasolevale kanalisatsioonisüsteemile........................................... 12 2.7.1 Hummuli .......................................................................................................... 12 2.7.2 Jeti................................................................................................................... 12 2.8 Kanalisatsiooni tehnilised indikaatorid.............................................................. 13 2.9 Asulate investeeringuprojektid ......................................................................... 13 2.9.1 Hummuli aleviku investeeringud ...................................................................... 13 2.9.2 Jeti -

Kastre Valla Üldplaneering

Registrikood 10171636 Riia 35, Tartu 50410 Tel 730 0310 [email protected] TÖÖ NR 2020-055 Asukoht (L-Est’97) X 6468461 Y 678620 Kastre valla üldplaneering lähteseisukohad Objekti aadress: TARTUMAA, KASTRE VALD Tellija: KASTRE VALLAVALITSUS Töö täitja: Kobras AS Juhataja: URMAS URI Projektijuht/planeerija: TEELE NIGOLA Volitatud maastikuarhitekt, tase 7 Volitatud ruumilise keskkonna planeerija, tase 7 Planeerija: PIIA KIRSIMÄE Kontrollis: ENE KÕND Mai 2020 TARTU Kastre valla üldplaneering Lähteseisukohad Üldinfo TÖÖ NIMETUS: Kastre valla üldplaneering: lähteseisukohad OBJEKTI ASUKOHT: Tartumaa, Kastre vald TÖÖ EESMÄRK: Üldplaneeringu koostamine Tartumaa Kastre vallale TÖÖ LIIK: Üldplaneering TÖÖ TELLIJA JA Kastre Vallavalitsus ÜLDPLANEERINGU Kurepalu, 62113 KOOSTAMISE KORRALDAJA: Kastre vald Tartu maakond Kontaktisik: Karen Katri Voll keskkonnaspetsialist Tel 5341 4205 [email protected] TÖÖ TÄITJA: Kobras AS Registrikood 10171636 Riia 35, 50410 Tartu Tel 730 0310 http://www.kobras.ee Projektijuht: Teele Nigola - maastikuarhitekt-planeerija Tel 730 0310, 518 7602 [email protected] Töö koostajad: Piia Kirsimäe- kartograaf-geoinformaatik, planeerija Silvia Türkson- planeerija assistent Konsultandid: Urmas Uri - geoloog, keskkonnaekspert (KMH0046) Reet Lehtla - maastikuarhitekt-planeerija Noeela Kulm - keskkonnaekspert Erki Kõnd - projektijuht, projekteerija Kontrollijad: Reet Lehtla - maastikuarhitekt-planeerija Ene Kõnd - tehniline kontrollija Kobras AS töö nr 2020-055 Objekti aadress: Tartumaa, Kastre vald 2 / 17 Kastre valla üldplaneering -

Jahipiirkonna Kasutusõiguse Loa Vorm Jahipiirkonna

Keskkonnaministri 19.07.2013. a määrus nr 56 „Jahipiirkonna kasutusõiguse loa vorm" Lisa JAHIPIIRKONNA KASUTUSÕIGUSE LOA VORM JAHIPIIRKONNA KASUTUSÕIGUSE LUBA nr TAR- 6 Kambja, JAH1000262 (jahipiirkonna nimi) 1. Jahipiirkonna kasutaja andmed: 1.1. Jahipiirkonna kasutaja nimi Kambja Jahiselts 1.2. Registrikood 80078909 1.3. Aadress Võru 80, 50111 Tartu 1.4. Esindaja nimi Veljo Jalak 1.5. Kontaktinfo Telefoni number 501 3431 Faksi number E-posti aadress [email protected] 2. Jahipiirkonna kasutusõiguse loa andja: 2.1. Asutuse nimi, regioon Keskkonnaamet 2.2. Registrikood 70008658 2.3. Aadress Narva mnt 7a, 15172 Tallinn 2.4. Loa koostanud ametniku nimi Hettel Mets 2.5. Ametikoht Jahinduse spetsialist 2.6. Kontaktinfo Telefoni number 7762422,5289690 Faksi number 7762411 Elektronposti aadress [email protected] 3. Jahipiirkonna kasutusõiguse loa: 3.1. kehtivuse alguse kuupäev 01.06.2013 3.2. Loa andja Nimi/Allkiri Rainis Uiga Ametinimetus Regiooni juhataja 3.3. Vastuvõtja Nimi/Allkiri Volli Aleksejev Ametinimetus juhatuse liige 3.4. Luba on kehtiv 31.05.2023 kuni 3.5. Vaidlustamine Käesolevat jahipiirkonna kasutusõiguse luba on võimalik vaidlustada 30 päeva jooksul selle tea tavaks tegemisest arvates, esitades vaide loa andjale haldusmenetluse seaduse sätestatud korras või esitades kaebuse halduskohtusse halduskohtumenetluse seadustikus sätestatud korras. 4. Seadusest või kaitstava loodusobjekti kaitse-eeskirjast tulenevad piirangud ja tingimused: 4.1. Objekti Raanitsa, Reolasoo ja Oomiste väike-konnakotka püsielupaik Looduskaitseseaduse § 14 lg 1 p 6, § 53 lg 1 ja nimetus/ keskkonnaministri 19.04.2010 määruse nr 12 § 4 lg 4 ja § 5 lg 1 lähtuvad piirangud: • Inimeste viibimine ja piirangu kirjeldus jahipidamine on lubatud püsielupaigas 01. septembrist kuni 14. märtsini. -

1 Estonian University of Life Sciences Kreutzwaldi 1

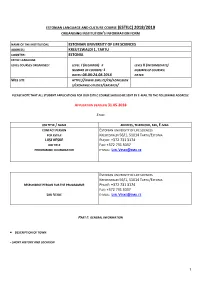

ESTONIAN LANGUAGE AND CULTURE COURSE (ESTILC) 2018/2019 ORGANISING INSTITUTION ’S INFORMATION FORM NAME OF THE INSTITUTION : ESTONIAN UNIVERSITY OF LIFE SCIENCES ADDRESS : KREUTZWALDI 1, TARTU COUNTRY : ESTONIA ESTILC LANGUAGE LEVEL COURSES ORGANISED: LEVEL I (BEGINNER ) X LEVEL II (INTERMEDIATE ) NUMBER OF COURSES : 1 NUMBER OF COURSES : DATES : 08.08-24.08.2018 DATES : WEB SITE HTTPS :// WWW .EMU .EE /EN /ADMISSION S/EXCHANGE -STUDIES /ERASMUS / PLEASE NOTE THAT ALL STUDENT APPLICATIONS FOR OUR ESTILC COURSE SHOULD BE SENT BY E -MAIL TO THE FOLLOWING ADDRESS : APPLICATION DEADLINE 31.05.2018 STAFF JOB TITLE / NAME ADDRESS , TELEPHONE , FAX , E-MAIL CONTACT PERSON ESTONIAN UNIVERSITY OF LIFE SCIENCES FOR ESTILC KREUTZWALDI 56/1, 51014 TARTU /E STONIA LIISI VESKE PHONE : +372 731 3174 JOB TITLE FAX : +372 731 3037 PROGRAMME COORDINATOR E-MAIL : LIISI .V ESKE @EMU .EE ESTONIAN UNIVERSITY OF LIFE SCIENCES KREUTZWALDI 56/1, 51014 TARTU /E STONIA RESPONSIBLE PERSON FOR THE PROGRAMME PHONE : +372 731 3174 FAX : +372 731 3037 LIISI VESKE E-MAIL : LIISI .V ESKE @EMU .EE PART I: GENERAL INFORMATION • DESCRIPTION OF TOWN - SHORT HISTORY AND LOCATION 1 Tartu is the second largest city of Estonia. Tartu is located 185 kilometres to south from the capital Tallinn. Tartu is known also as the centre of Southern Estonia. The Emajõgi River, which connects the two largest lakes (Võrtsjärv and Peipsi) of Estonia, flows for the length of 10 kilometres within the city limits and adds colour to the city. As Tartu has been under control of various rulers throughout its history, there are various names for the city in different languages. -

Gggggggggggggggggggg

Amme j L e v a l a Kiisli paisjrv Nava oja P a k a s t e Pala oja Punikvere K a a v e r e pkr Rahivere P u t u H a a v a k i v i P u n i k v e r e raba pkr Kurista Uhmardu j K i i s l i P r s i k i v i ROHELINE VRGUSTIK H r j a n u r m e S A A R E P i i r i v a r b e TAUSTINFO Kalevi S v a l e p a K i r t s i Palamuse P a l a Kaave j Kassinurme pkr E e r i k v e r e PEDJA J Palamuse kirik Alekõrre oja KALLASTE Levala Kallaste sadam Riigi tasandi tugialad (T1) soo pkr K37 T o r i l a T12 riigipiir Sadukla kr kaitsmata põhjaveega ala S u l u s t v e r e Laeva j R a h i v e r e Luiska oja Kupu kr V a n a s s a a r e Torila oja Neanurme j T a g u m a a Pala oja Amme j K u d i n a T23 Piirkondliku tasandi tugialad (T2) K i v i m e Kallaste R a a d i v e r e S a a r j r v e kirik maakonnapiir looduskaitseala või maastikukaitseala K a s s i n u r m e P e d a s s a a r e oja S a d u k l a J õ u n e P A L A Passi Nava oja KÄÄPA J M o k u K21 Piirkondliku tasandi ribastruktuurid Pudivere valla/linna piir Ramsari ala Kaarepere Vljakla H a a p s i p e a Pari kr K a a r e p e r e Jıemıisa jrv Haava P u s i P u d i v e r e Puustuge oja Saare jv Pudivere oja Kaarepere paisjrv K a i u Sııru med Kohaliku tasandi tugialad (T3) Srgjrv T34 S õ õ r u kivi j 3 Papijrv kla lahkmejoon Turba tootmisvli Prossa jv Ronisoo L u s t i v e r e L u u a V a i d a v e r e Saare Lutikajrv P r a P i k k j r v e K o k o r a Kaiu jrv Linaleo K33 Kohaliku tasandi ribastruktuurid E h a v e r e Kaarepere Pikkjrv Ehavere paisjrv s o o Kogri jv Kogrekla kr hoonestatud -

RMK ANNUAL REPORT 2015 ANNUAL REPORT 2015 Address by the Chairman of the Board

RMK ANNUAL REPORT 2015 ANNUAL REPORT 2015 Address by the Chairman of the Board 3-4 ADDRESS BY THE CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD 36-43 ACTIVITIES IN NATURE AND NATURE EDUCATION IN PRAISE OF DIVERSITY 3 MOVING AROUND IN NATURE 38 IN PRAISE OF NATURE EDUCATION 40 5 TEN FACTS ABOUT RMK 5 SAGADI FOREST CENTRE 40 ELISTVERE ANIMAL PARK 41 NATURE CAMERA 42 diversity CHRISTMAS TREES 42 6-13 ABOUT THE ORGANISATION HERITAGE CULTURE 43 ALL OVER ESTONIA 8 Aigar Kallas EMPLOYEES 9 Chairman of the Management Board of RMK HONOUR BOARD 10 COOPERATION PROJECTS 12 44-49 RESEARCH WORK APPLIED RESEARCH PROJECTS 46 USE OF RESEARCH RESULTS 48 SCHOLARSHIPS 49 14-27 FOREST MANAGEMENT FOREST LAND OVERVIEW 16 CUTTING WORKS 17 The motto of the yearbook, containing an over- FOREST RENEWAL 18 50-55 FINANCIAL SUMMARY view of 2015, is diversity. RMK and the forests PLANT GROWING 20 BALANCE SHEET 52 entrusted to our care in Estonia are both diverse. TIMBER MARKETING 22 INCOME STATEMENT 54 FOREST IMPROVEMENT 24 AUDITOR’S REPORT 55 Curiously enough, the activity which RMK’s staff WASTE COLLECTION 25 and its contractual partners spend the most This knowledge is essential for a number of FOREST FIRES 26 HUNTING 26 energy on is not the one we are most commonly reasons. Firstly, it confirms that the years of work associated with. Growing young trees, caring for dedicated to creating free recreational possibi- their growth conditions, replacing an old forest lities have been a success. Secondly, it shows generation with a new one at the right time, and 28-35 NATURE PROTECTION that RMK’s primary role of performing nature timber sales are areas in which RMK is active, but protection works is growing in terms of visibility.