The Two-Way Transmission Between Jingshan Temple and Kench¯O-Ji

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Path to Bodhidharma

The Path to Bodhidharma The teachings of Shodo Harada Roshi 1 Table of Contents Preface................................................................................................ 3 Bodhidharma’s Outline of Practice ..................................................... 5 Zazen ................................................................................................ 52 Hakuin and His Song of Zazen ......................................................... 71 Sesshin ........................................................................................... 100 Enlightenment ................................................................................. 115 Work and Society ............................................................................ 125 Kobe, January 1995 ........................................................................ 139 Questions and Answers ................................................................... 148 Glossary .......................................................................................... 174 2 Preface Shodo Harada, the abbot of Sogenji, a three-hundred-year-old Rinzai Zen Temple in Okayama, Japan, is the Dharma heir of Yamada Mumon Roshi (1890-1988), one of the great Rinzai masters of the twentieth century. Harada Roshi offers his teachings to everyone, ordained monks and laypeople, men and women, young and old, from all parts of the world. His students have begun more than a dozen affiliated Zen groups, known as One Drop Zendos, in the United States, Europe, and Asia. The material -

The Saddharmapurdarikaas the Prediction

The JapaneseAssociationJapanese Association of Indian and Buddhist Studies Journal oflndian and Buddhist Studies Vol. 64, No. 3, March 2016 (113) The Saddharmapurdarika as the Prediction ofAll the Sentient Beings' Attaining Buddhahood: With Special Focus on the Sadaparibhata-parivarta SuzuKi Takayasu 1. The Aim ofThis Paper While the Saddharmapu4darika (Lotus SUtra, SP) repeatedly teaches that any person who speaks against the SP or against those who keep, read, preach, or explain the SP must experience severe retribution, it also teaches that those who keep, read, preach, or explain the SP shall attain a perfection of the six sense organs, i.e., eye, ear, nose, tongue, bodM and mind. These understandings have been considered the basis of the i] fo11owing teaching in Chapter lg ofthe SP (Sada'paribhUta-parivarta, SP 19): ' There once existed a Bodhisattva named SadaparibhUta. He did not read or preach any Buddhist scripture at all, but only continued to give prediction of attaining buddhahood to all the Buddhists who held the mistaken idea that they had already attainedenlightenment. ' Because ofhis prediction he was abused by them. ' They went to hell on the grounds of having abused him. The now arises: question ' Why did they have to experience such severe retribution for abusing Sada- paribhUta who did not read or preach the SP. To this question the fbllowing interpretation has been general: ' The SP is the prediction of all the sentient beings' attaining buddhahood. Through giving of this prediction to the Buddhists SadaparibhUta had essentially read and preached the SP. It is true that Chapter lo of the 5P predicts that all the sentient beings can attain buddhahood. -

Zen Is a Form of Buddhism That Developed First in China Around the Sixth Century CE and Then Spread from China to Korea, Vietnam and Japan

Zen Zen is a form of Buddhism that developed first in China around the sixth century CE and then spread from China to Korea, Vietnam and Japan. The term Zen is just the Japanese way of saying the Chinese word Chan ( 禪 ), which is the Chinese translation of the Sanskrit word Dhyāna (Jhāna in Pali), which means "meditation." In the image above one sees on the left the character 禪 in Japanese calligraphy and on the right an ensō, or Zen circle. In Japan the drawing of such a circle is considered a high art, the expression of a moment of enlightenment by the Zen master calligrapher. The tradition known as Chan Buddhism in China, and Zen Buddhism in Japan, brings together Mahāyāna Buddhism and Daoism. This confluence of Buddhism and Daoism in Zen is most obvious in the Chinese script on the left which reads: "The heart-mind (xin 心) is the buddha (佛), the buddha (佛) is the path (dao 道), the path (dao 道) is meditation (chan 禪)." The line is from a text called the Bloodstream Sermon attributed to the legendary Bodhidharma. An Indian meditation master, Bodhidharma had come to China around 520 CE and in time would come to be regarded as the first patriarch of Chan Buddhism. In Bodhidharma’s Bloodstream Introduction to Asian Philosophy Zen Buddhism Sermon (in the Chan Buddhism online selections) it is evident that Bodhidharma had absorbed something of Daoism after he came to China. The Mahāyāna Buddhist teachings that are most evident in Bodhidharma’s text are the teachings of emptiness (Śūnyatā) from the Prajñāpāramitā Sūtras as well as the notion of the buddha-nature (dharmakāya) that is part of the Mahāyāna teaching of the three bodies (trikāya) of the Buddha. -

Of ZHENJIANG

江 苏 Culture Scenery Gourmet Useful Info © Municipal Bureau of Culture, Radio, Film and Tourism of ©Yancheng Kou Shanqin Introduction & Map 镇江简介&地图 of ZHENJIANG Zhenjiang is a southern Jiangsu city that sits on the southern shore of the Yangtze River. The place is featured in Chinese legend 'The Legend of the White Snake'. A large number of precious stone stelae could be found here. Literature Jinshan, Jiaoshan and Beigushan mountains, or the 'Three Peaks of Jingkou', 文学名山 Pilgrims are popular attractions in the city. Zhenjiang's very unique food culture is represented by three unusual food - vinegar that cannot go bad over time, pork trotter aspic which is eaten during tea time, and noodles that are cooked along with a pot lid. Jinshan Mountain Named as one of the 'Three Peaks of Jingkou' together with Jiaoshan mountain and Beigushan mountain, visitors usually visit N Jinshan mountain to experience the ambience and story background depicted in the 'White Snake Folklore'. Jinshan Temple is built at the LIANYUNGANG mountainside, ascending to the mountaintop, featuring a unique XUZHOU mountain view. SUQIAN Beigushan Mountain HUAI'AN YANCHENG Situated at the edge of Yangtze River, overlooking the entire river. This is where the well-known Ganlu Temple located, and also where the legendary warlord Liu Bei met his wife. Other than that, there are many spots associated with the history of Three Kingdoms. A famous scholar from Southern Song dynasty once left his famous quote about parenthood with a reference on the Three Kingdoms tale here. YANGZHOU NANJING TAIZHOU © Municipal Bureau of Culture, Radio, NANTONG Film and Tourism of Zhenjiang ZHENJIANG WUXI CHANGZHOU SUZHOU Beijing SHANGHAI Jiangsu Province Shanghai 01 © Baohua Mountain National Park © Chang Yungchieh Monuments 文化名山 Cultural History 历史文化 Cultural Maoshan Mountain Baohua Mountain For Chinese movie fans, you are probably familiar with Maoshan The most notable temple in the Vinaya School in Buddhism has to be Taoist as a movie icon. -

A Departure for Returning to Sabha: a Study of Koan Practice of Silence Jea Sophia Oh West Chester University of Pennsylvania, [email protected]

West Chester University Digital Commons @ West Chester University Philosophy College of Arts & Humanities 12-2017 A departure for returning to sabha: a study of koan practice of silence Jea Sophia Oh West Chester University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcupa.edu/phil_facpub Part of the Buddhist Studies Commons Recommended Citation Oh, J. S. (2017). A departure for returning to sabha: a study of koan practice of silence. International Journal of Dharma Studies, 5(12) http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s40613-017-0059-7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Humanities at Digital Commons @ West Chester University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ West Chester University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Oh International Journal of Dharma Studies (2017) 5:12 International Journal of DOI 10.1186/s40613-017-0059-7 Dharma Studies RESEARCH Open Access A departure for returning to sabha: a study of koan practice of silence Jea Sophia Oh Correspondence: [email protected] West Chester University of Abstract Pennsylvania, 700 S High St. AND 108D, West Chester, PA 19383, USA This paper deals with koan practice of silence through analyzing the Korean Zen Buddhist film, Why Has Boddhidharma Left for the East? (Bae, Yong-Kyun, Why Has Bodhidharma Left for the East? 1989). This paper follows Kibong's path along with the Buddha's journey of 1) departure, 2) journey in the middle way, and 3) returning with a particular focus on koan practice of silence as the transformative element of enlightenment. -

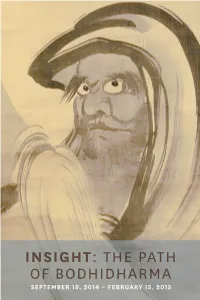

Insight: the Path of Bodhidharma

INSIGHT: THE PATH OF BODHIDHARMA SEPTEMBER 19, 2014 – FEBRUARY 15, 2015 Credited with introducing Chan (Zen in Japanese) Buddhism to China in the sixth century, the Indian monk Bodhidharma (known as Daruma in Japan) has become a well-known subject in Buddhist art. As Chan Buddhism gained popularity, various legends associated with the Chan patriarch evolved, and artists began to depict those legends alongside his conventional portraits. Traditional depictions of Bodhidharma were executed in ink monochrome with free, expressive brush strokes, alluding to his teaching on the spontaneous nature of reaching enlightenment through meditation. During the Edo period (1603-1868) in Japan, the depiction of this pious monk’s stern expression went through a radical change as he was often paired with a courtesan of the pleasure quarters—a parody to expose the hypocrisy of society. Today, Bodhidharma is still widely represented both in fine art and as a pop culture icon of good luck. Through an array of objects from paintings and sculptures to decorative objects and toys, Insight: The Path of Bodhidharma illustrates the visual and conceptual shift in depictions of this religious figure from the 17th century through today. BODHIDHARMA AS CHAN PATRIARCH One of the most common portrayals of Bodhidharma is a bust portrait revealing only the upper half of his body. In a three- quarter profile, he was frequently depicted in ways that emphasize his non-East Asian heritage and iconoclastic persona with large glaring eyes, a prominent nose and beard—sometimes an earring and red hooded robe. The primary goal of Bodhidharma’s teaching is to reach personal enlightenment through meditation that clears one’s mind from distracting thoughts and worldly concerns. -

Contents Transcriptions Romanization Zen 1 Chinese Chán Sanskrit Name 1.1 Periodisation Sanskrit Dhyāna 1.2 Origins and Taoist Influences (C

7/11/2014 Zen - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Zen From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Zen is a school of Mahayana Buddhism[note 1] that Zen developed in China during the 6th century as Chán. From China, Zen spread south to Vietnam, northeast to Korea and Chinese name east to Japan.[2] Simplified Chinese 禅 Traditional Chinese 禪 The word Zen is derived from the Japanese pronunciation of the Middle Chinese word 禪 (dʑjen) (pinyin: Chán), which in Transcriptions turn is derived from the Sanskrit word dhyāna,[3] which can Mandarin be approximately translated as "absorption" or "meditative Hanyu Pinyin Chán state".[4] Cantonese Zen emphasizes insight into Buddha-nature and the personal Jyutping Sim4 expression of this insight in daily life, especially for the benefit Middle Chinese [5][6] of others. As such, it de-emphasizes mere knowledge of Middle Chinese dʑjen sutras and doctrine[7][8] and favors direct understanding Vietnamese name through zazen and interaction with an accomplished Vietnamese Thiền teacher.[9] Korean name The teachings of Zen include various sources of Mahāyāna Hangul 선 thought, especially Yogācāra, the Tathāgatagarbha Sutras and Huayan, with their emphasis on Buddha-nature, totality, Hanja 禪 and the Bodhisattva-ideal.[10][11] The Prajñāpāramitā Transcriptions literature[12] and, to a lesser extent, Madhyamaka have also Revised Romanization Seon been influential. Japanese name Kanji 禅 Contents Transcriptions Romanization Zen 1 Chinese Chán Sanskrit name 1.1 Periodisation Sanskrit dhyāna 1.2 Origins and Taoist influences (c. 200- 500) 1.3 Legendary or Proto-Chán - Six Patriarchs (c. 500-600) 1.4 Early Chán - Tang Dynasty (c. -

Nothing Transcended

Nothing Transcended An examination of the metaphysical implications of interdependence Justin Shimeld, BA (Hons) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Tasmania April 2012 This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of the my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. Signed: Date: Justin Shimeld 2 This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. 3 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisors for all their help and support - Jeff Malpas for his feedback and insightful suggestions, Wayne Hudson for helping me to find my way and Sonam Thakchoe for all his time and wisdom. It was Sonam’s presence and attitude which inspired me to look further into Buddhism and to investigate a way out of the ‘nihilism’ of my Honours project – research which became the foundation of this thesis. I would also like to thank my two anonymous examiners for their helpful comments. A special thanks to David O’Brien, a master whose interests and drive for knowledge are unbound by any field. He has taught me so much and also read my draft, giving invaluable feedback, particularly, with regard to my use of commas, grammatical clarification! I am indebted to my friends and colleagues at the School of Philosophy at UTas who created a rich atmosphere provoking thought across diverse subjects, through papers, seminars and conversations. -

Soundscape of the West Lake Scenic Area with Profound Cultural Background—A Case Study of Evening Bell Ringing in Jingci Temple, China*

Ge et al. / J Zhejiang Univ-Sci A (Appl Phys & Eng) 2013 14(3):219-229 219 Journal of Zhejiang University-SCIENCE A (Applied Physics & Engineering) ISSN 1673-565X (Print); ISSN 1862-1775 (Online) www.zju.edu.cn/jzus; www.springerlink.com E-mail: [email protected] Soundscape of the West Lake Scenic Area with profound cultural background—a case study of * Evening Bell Ringing in Jingci Temple, China Jian GE†1,2, Min GUO1,2, Miao YUE1,3 (1Deptartment of Architecture, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310058, China) (2State Key Lab of Subtropical Building Science, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou 510640, China) (3Deptartment of Architecture and Art, Zhejiang College of Construction, Hangzhou 311231, China) †E-mail: [email protected] Received June 25, 2012; Revision accepted Sept. 27, 2012; Crosschecked Feb. 22, 2013 Abstract: From the case study of Evening Bell Ringing at Nanping Hill, one of the West Lake Cultural Landscapes in Hangzhou, China, we investigated the soundscape of a scenic area with a profound cultural background. First, we conducted the soundscape physical index of the area in both winter and spring seasons to analyze its objective graphical expression. Second, we focused on people’s reactions to the soundscape in order to obtain a subjective evaluation of each component in the soundscape and integrated environment. Then, the relationship between the objective data and the subjective evaluation was analyzed. Finally, the impacts of the natural environment, history, and cultural factors on the evaluation of the Jingci Temple soundscape were studied. It was found that natural sounds, cultural sounds, and historic sounds were widely acclaimed in people’s subjective feelings, which indicated the close relationships among historical and cultural background, soundscape, and natural environment. -

Zen) Buddhism

THE SPREAD OF CHAN (ZEN) BUDDHISM T. Grif\ th Foulk (Sarah Lawrence College, New York) 1. Introduction This chapter deals with the development and spread of the so-called Chan School of Buddhism in China, Japan, and the West. In its East Asian setting, at least, the spread of Chan must be viewed rather dif- ferently than the spread of Buddhism as a whole, for by all accounts (both traditional and modern) Chan was a movement that initially ] ourished within, or (as some would have it) in reaction against, a Buddhist monastic order that had already been active in China for a number of centuries. By the same token, at the times when the Chan movement spread to Korea and Japan, it did not appear as the har- binger of Buddhism itself, which was already well established in those countries, but rather as the most recent in a series of importations of Buddhism from China. The situation in the West, of course, is much different. Here, Chan—usually referred to (using the Japanese pronun- ciation) as Zen—has indeed been at the vanguard of the spread of Buddhism as a whole. I begin this chapter by re] ecting on what we (modern scholars) mean when we speak of the spread of Buddhism, contrasting that with a few of the traditional ways in which Asian Buddhists themselves, from an insider’s or normative point of view, have conceived the transmission of the Buddha’s teachings (Skt. buddhadharma, Chin. fofa 佛法). I then turn to the main topic: the spread of Chan. -

Seon Dialogues 禪語錄禪語錄 Seonseon Dialoguesdialogues John Jorgensen

8 COLLECTED WORKS OF KOREAN BUDDHISM 8 SEON DIALOGUES 禪語錄禪語錄 SEONSEON DIALOGUESDIALOGUES JOHN JORGENSEN COLLECTED WORKS OF KOREAN BUDDHISM VOLUME 8 禪語錄 SEON DIALOGUES Collected Works of Korean Buddhism, Vol. 8 Seon Dialogues Edited and Translated by John Jorgensen Published by the Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism Distributed by the Compilation Committee of Korean Buddhist Thought 45 Gyeonji-dong, Jongno-gu, Seoul, 110-170, Korea / T. 82-2-725-0364 / F. 82-2-725-0365 First printed on June 25, 2012 Designed by ahn graphics ltd. Printed by Chun-il Munhwasa, Paju, Korea © 2012 by the Compilation Committee of Korean Buddhist Thought, Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism This project has been supported by the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, Republic of Korea. ISBN: 978-89-94117-12-6 ISBN: 978-89-94117-17-1 (Set) Printed in Korea COLLECTED WORKS OF KOREAN BUDDHISM VOLUME 8 禪語錄 SEON DIALOGUES EDITED AND TRANSLATED BY JOHN JORGENSEN i Preface to The Collected Works of Korean Buddhism At the start of the twenty-first century, humanity looked with hope on the dawning of a new millennium. A decade later, however, the global village still faces the continued reality of suffering, whether it is the slaughter of innocents in politically volatile regions, the ongoing economic crisis that currently roils the world financial system, or repeated natural disasters. Buddhism has always taught that the world is inherently unstable and its teachings are rooted in the perception of the three marks that govern all conditioned existence: impermanence, suffering, and non-self. Indeed, the veracity of the Buddhist worldview continues to be borne out by our collective experience today. -

A Geographic History of Song-Dynasty Chan Buddhism: the Decline of the Yunmen Lineage

decline of the yunmen lineage Asia Major (2019) 3d ser. Vol. 32.1: 113-60 jason protass A Geographic History of Song-Dynasty Chan Buddhism: The Decline of the Yunmen Lineage abstract: For a century during China’s Northern Song era, the Yunmen Chan lineage, one of several such regional networks, rose to dominance in the east and north and then abruptly disappeared. Whereas others suggested the decline was caused by a doctri- nal problem, this essay argues that the geopolitics of the Song–Jin wars were the pri- mary cause. The argument builds upon a dataset of Chan abbots gleaned from Flame Records. A chronological series of maps shows that Chan lineages were regionally based. Moreover, Song-era writers knew of regional differences among Chan lin- eages and suggested that regionalism was part of Chan identity: this corroborates my assertion. The essay turns to local gazetteers and early-Southern Song texts that re- cord the impacts of the Song–Jin wars on monasteries in regions associated with the Yunmen lineage. Finally, I consider reasons why the few Yunmen monks who sur- vived into the Southern Song did not reconstitute their lineage, and discuss a small group of Yunmen monks who endured in north China under Jin and Yuan control. keywords: Chan, Buddhism, geographic history, mapping, spatial data n 1101, the recently installed emperor Huizong 徽宗 (r. 1100–1126) I authored a preface for a new collection of Chan 禪 religious biogra- phies, Record of the Continuation of the Flame of the Jianzhong Jingguo Era (Jianzhong Jingguo xudeng lu 建中靖國續燈錄, hereafter Continuation of the Flame).1 The emperor praised the old “five [Chan] lineages, each ex- celling in a family style 五宗各擅家風,” a semimythical system promul- gated by the Chan tradition itself to assert a shared identity among the ramifying branches of master-disciple relationships.