The 1812 Streets of Cambridgeport

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

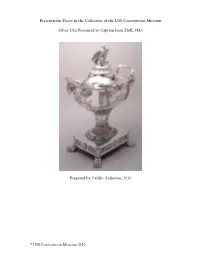

Symbolism of Commander Isaac Hull's

Presentation Pieces in the Collection of the USS Constitution Museum Silver Urn Presented to Captain Isaac Hull, 1813 Prepared by Caitlin Anderson, 2010 © USS Constitution Museum 2010 What is it? [Silver urn presented to Capt. Isaac Hull. Thomas Fletcher & Sidney Gardiner. Philadelphia, 1813. Private Collection.](1787–1827) Silver; h. 29 1/2 When is it from? © USS Constitution Museum 2010 1813 Physical Characteristics: The urn (known as a vase when it was made)1 is 29.5 inches high, 22 inches wide, and 12 inches deep. It is made entirely of sterling silver. The workmanship exhibits a variety of techniques, including cast, applied, incised, chased, repoussé (hammered from behind), embossed, and engraved decorations.2 Its overall form is that of a Greek ceremonial urn, and it is decorated with various classical motifs, an engraved scene of the battle between the USS Constitution and the HMS Guerriere, and an inscription reading: The Citizens of Philadelphia, at a meeting convened on the 5th of Septr. 1812, voted/ this Urn, to be presented in their name to CAPTAIN ISAAC HULL, Commander of the/ United States Frigate Constitution, as a testimonial of their sense of his distinguished/ gallantry and conduct, in bringing to action, and subduing the British Frigate Guerriere,/ on the 19th day of August 1812, and of the eminent service he has rendered to his/ Country, by achieving, in the first naval conflict of the war, a most signal and decisive/ victory, over a foe that had till then challenged an unrivalled superiority on the/ ocean, and thus establishing the claim of our Navy to the affection and confidence/ of the Nation/ Engraved by W. -

The Life and Family of Admiral Sir Philip Broke, Bt

FRIENDS OF HMS TRINCOMALEE SUMMER 2016 The Life of Sir Philip Broke TS Foudroyant at the Movies Mess Deck Crossword / Wordsearch / Future events Annual General Meeting Notice is hereby given of our: Annual General Meeting 2016 Wednesday 14th September at 7.30pm Hart Village Hall, Hartlepool, TS27 3AW AGENDA: 1. Welcome and apologies for absence 2. Minutes of the last Annual General Meeting held on 23rd September 2015 3. Chairman’s report 4. Honorary Treasurer’s report and accounts for the 12 month period ending 31st March 2016 5. Election of Trustees 6. Appointment of Honorary Auditor 7. Any other business (Notified to the Secretary prior to the meeting) Members interested in joining the Committee are warmly encouraged to make themselves known to the Secretary of the ‘Friends’. All candidates for election need at least one nominee from the present Committee. The closing time for all nominations to be submitted to the Secretary is 2nd September 2016. Ian Purdy Hon. Secretary Any correspondence concerning the Friends Association should be sent to: The Secretary, Ian Purdy 39 The Poplars, Wolviston, Billingham TS22 5LY Tel: 01740 644381 E-mail: [email protected] Correspondence and contributions for the magazine to: The Editor, Hugh Turner Chevin House, 30 Kingfisher Close, Bishop Cuthbert, Hartlepool TS26 0GA Tel: 01429 236848 E-Mail: [email protected] Membership matters directed to: The Membership Secretary, Martin Barker The Friends of HMS Trincomalee, Jackson Dock, Maritime Avenue, Hartlepool TS24 0XZ E-Mail: [email protected] –– 22 –– Editorial At the time of writing this editorial, our negotiations with the National Museum of the Royal Navy are still in progress. -

1 Overview of USS Constitution Re-Builds & Restorations USS

Overview of USS Constitution Re-builds & Restorations USS Constitution has undergone numerous “re-builds”, “re-fits”, “over hauls”, or “restorations” throughout her more than 218-year career. As early as 1801, she received repairs after her first sortie to the Caribbean during the Quasi-War with France. In 1803, six years after her launch, she was hove-down in Boston at May’s Wharf to have her underwater copper sheathing replaced prior to sailing to the Mediterranean as Commodore Edward Preble’s flagship in the Barbary War. In 1819, Isaac Hull, who had served aboard USS Constitution as a young lieutenant during the Quasi-War and then as her first War of 1812 captain, wrote to Stephen Decatur: “…[Constitution had received] a thorough repair…about eight years after she was built – every beam in her was new, and all the ceilings under the orlops were found rotten, and her plank outside from the water’s edge to the Gunwale were taken off and new put on.”1 Storms, battle, and accidents all contributed to the general deterioration of the ship, alongside the natural decay of her wooden structure, hemp rigging, and flax sails. The damage that she received after her War of 1812 battles with HMS Guerriere and HMS Java, to her masts and yards, rigging and sails, and her hull was repaired in the Charlestown Navy Yard. Details of the repair work can be found in RG 217, “4th Auditor’s Settled Accounts, National Archives”. Constitution’s overhaul of 1820-1821, just prior to her return to the Mediterranean, saw the Charlestown Navy Yard carpenters digging shot out of her hull, remnants left over from her dramatic 1815 battle against HMS Cyane and HMS Levant. -

Signers of the United States Declaration of Independence Table of Contents

SIGNERS OF THE UNITED STATES DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE 56 Men Who Risked It All Life, Family, Fortune, Health, Future Compiled by Bob Hampton First Edition - 2014 1 SIGNERS OF THE UNITED STATES DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTON Page Table of Contents………………………………………………………………...………………2 Overview………………………………………………………………………………...………..5 Painting by John Trumbull……………………………………………………………………...7 Summary of Aftermath……………………………………………….………………...……….8 Independence Day Quiz…………………………………………………….……...………...…11 NEW HAMPSHIRE Josiah Bartlett………………………………………………………………………………..…12 William Whipple..........................................................................................................................15 Matthew Thornton……………………………………………………………………...…........18 MASSACHUSETTS Samuel Adams………………………………………………………………………………..…21 John Adams………………………………………………………………………………..……25 John Hancock………………………………………………………………………………..….29 Robert Treat Paine………………………………………………………………………….….32 Elbridge Gerry……………………………………………………………………....…….……35 RHODE ISLAND Stephen Hopkins………………………………………………………………………….…….38 William Ellery……………………………………………………………………………….….41 CONNECTICUT Roger Sherman…………………………………………………………………………..……...45 Samuel Huntington…………………………………………………………………….……….48 William Williams……………………………………………………………………………….51 Oliver Wolcott…………………………………………………………………………….…….54 NEW YORK William Floyd………………………………………………………………………….………..57 Philip Livingston…………………………………………………………………………….….60 Francis Lewis…………………………………………………………………………....…..…..64 Lewis Morris………………………………………………………………………………….…67 -

Argonauta, Vol XXX, No 4 (Autumn 2013)

ARGONAUTA The Newsletter of The Canadian Nautical Research Society / Société canadienne pour la recherche nautique Volume XXX Number 4 Autumn 2013 ARGONAUTA Founded 1984 by Kenneth MacKenzie ISSN No. 2291-5427 Editors Isabel Campbell and Colleen McKee Jean Martin ~ French Editor Winston Kip Scoville ~ Distribution Manager Argonauta Editorial Office c/o Isabel Campbell 2067 Alta Vista Dr. Ottawa ON K1H 7L4 e-mail submissions to: [email protected] or [email protected] ARGONAUTA is published four times a year—Winter, Spring, Summer and Autumn The Canadian Nautical Research Society Executive Officers President: Maurice Smith, Kingston Past President: Paul Adamthwaite, Picton 1st Vice President: Chris Madsen, Toronto 2nd Vice President: Roger Sarty, Kitchener Treasurer: Errolyn Humphreys, Ottawa Secretary: Rob Davison, Waterloo Membership Secretary: Faye Kert, Ottawa Councillor: Chris Bell, Halifax Councillor: Isabel Campbell, Ottawa Councillor: Richard O. Mayne, Winnipeg Councillor: Barbara Winters, Ottawa Membership Business: 200 Fifth Avenue, Ottawa, Ontario, K1S 2N2, Canada e-mail: [email protected] Annual Membership including four issues of ARGONAUTA and four issues of THE NORTHERN MARINER/LE MARIN DU NORD: Within Canada: Individuals, $65.00; Institutions, $90.00; Students, $20.00 International: Individuals, $75.00; Institutions, $100.00; Students, $30.00 Our Website: http://www.cnrs-scrn.org Argonauta ~ Autumn ~ 2013 1 In This Issue Editorial 1-2 President’s Corner 3-4 Announcements 4-25 Legends of Magdalen Film 4-16 Call for Papers and Conferences 17-20 CNRS on Facebook 20-21 Perseverance – The Cdn Sea King Story 21 Salty Dips – New Cd 22 Book Launches 23-25 Being Interdisciplinary by Sam McLean 26-32 Editorial In this Autumn issue of Argonauta, President Maurice Smith ponders the importance of accumulated archival knowledge, bringing to our attention two extraordinary archival fonds held at the Marine Museum of the Great Lakes. -

The American Navy by Rear-Admiral French E

:*' 1 "J<v vT 3 'i o> -< •^^^ THE AMERICAN BOOKS A LIBRARY OF GOOD CITIZENSHIP " The American Books" are designed as a series of authoritative manuals, discussing problems of interest in America to-day. THE AMERICAN BOOKS THE AMERICAN COLLEGE BY ISAAC SHARPLESS THE INDIAN TO-DAY BY CHARLES A. EASTMAN COST OF LIVING BY FABIAN FRANKLIN THE AMERICAN NAVY BY REAR-ADMIRAL FRENCH E. CHADWICK, U. S. N. MUNICIPAL FREEDOM BY OSWALD RYAN AMERICAN LITERATURE BY LEON KELLNER (translated from THB GERMAN BY JULIA FRANKLIN) SOCIALISM IN AMERICA BY JOHN MACY AMERICAN IDEALS BY CLAYTON S. COOPER THE UNIVERSITY MOVEMENT BY IRA REMSEN THE AMERICAN SCHOOL BY WALTER S. HINCHMAN THE FEDERAL RESERVE BY H. PARKER WILLIS {For more extended notice of the series, see the last pages of this book.) The American Books The American Navy By Rear-Admiral French E. Chadwick (U. S. N., Retired) GARDEN CITY NEW YORK DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY 191S Copyright, 1915, by DOUBLEDAY, PaGE & CoMPANY All rights reserved, including that of translation into foreign languages, inxluding the Scandinavian m 21 1915 'CI, A 401 J 38 TO MY COMRADES OF THE NAVY PAST, PRESENT, AND FUTURE BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Rear-Admiral French Ensor Chadwick was born at Morgantown, W. Va., February 29, 1844. He was appointed to the U. S. Naval Academy from West Virginia (then part of Virginia) in 1861, and graduated in November, 1864. In the summer of 1864 he was attached to the Marblehead in pursuit of the Confederate steamers Florida and Tallahassee. After the Civil War he served successively in a number of vessels, and was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant-Commander in 1869; was instruc- tor at the Naval Academy; on sea-service, and on lighthouse duty (i 870-1 882); Naval Attache at the American Embassy in London (1882- 1889); commanded the Yorktown (1889-1891); was Chief Intelligence Officer (1892-1893); and Chief of the Bureau of Equipment (1893-1897). -

Ocm01251790-1863.Pdf (10.24Mb)

u ^- ^ " ±i t I c Hon. JONATHAN E. FIELD, President. 1. —George Dwight. IJ. — K. M. Mason. 1. — Francis Briwiej'. ll.-S. .1. Beal. 2.— George A. Shaw. .12 — Israel W. Andrews. 2.—Thomas Wright. 12.-J. C. Allen. 3. — W. F. Johnson. i'i. — Mellen Chamberlain 3.—H. P. Wakefield. 13.—Nathan Crocker. i.—J. E. Crane. J 4.—Thomas Rice, .Ir. 4.—G. H. Gilbert. 14.—F. M. Johnson. 5.—J. H. Mitchell. 15.—William L. Slade. 5. —Hartley Williams. 15—H. M. Richards. 6.—J. C. Tucker. 16. —Asher Joslin. 6.—M. B. Whitney. 16.—Hosea Crane. " 7. —Benjamin Dean. 17.— Albert Nichols. 7.—E. O. Haven. 17.—Otis Gary. 8.—William D. Swan. 18.—Peter Harvey. 8.—William R. Hill. 18.—George Whitney. 9.—.]. I. Baker. 19.—Hen^^' Carter. 9.—R. H. Libby. 19.—Robert Crawford. ]0.—E. F. Jeiiki*. 10.-—Joseph Breck. 20. —Samuel A. Brown. .JOHN MORIS?5KV, Sevii^aiU-ut-Anns. S. N. GIFFORU, aerk. Wigatorn gaHei-y ^ P=l F ISSu/faT-fii Lit Coiranoittoralllj of llitss3t|ttsttts. MANUAL FOR THE USE OF THE G-ENERAL COURT: CONTAINING THE RULES AND ORDERS OF THE TWO BRANCHES, TOGETHER WITH THE CONSTITUTION OF THE COMMONWEALTH, AND THAT OF THE UNITED STATES, A LIST OF THE EXECUTIVE, LEGISLATIVE, AND JUDICIAL DEPARTMENTS OF THE STATE GOVERNMENT, STATE INSTITUTIONS AND THEIR OFFICERS, COUNTY OFFICERS, AND OTHER STATISTICAL INFORMATION. Prepared, pursuant to Orders of the Legislature, BY S. N. GIFFORD and WM. S. ROBINSON. BOSTON: \yRIGHT & POTTER, STATE PRINTERS, No. 4 Spring Lane. 1863. CTommonbtaltfj of iBnssacf)useits. -

The 1812 Streets of Cambridgeport

The 1812 Streets of Cambridgeport The Last Battle of the Revolution Less than a quarter of a century after the close of the American Revolution, Great Britain and the United States were again in conflict. Britain and her allies were engaged in a long war with Napoleonic France. The shipping-related industries of the neutral United States benefited hugely, conducting trade with both sides. Hundreds of ships, built in yards on America’s Atlantic coast and manned by American sailors, carried goods, including foodstuffs and raw materials, to Europe and the West Indies. Merchants and farmers alike reaped the profits. In Cambridge, men made plans to profit from this brisk trade. “[T]he soaring hopes of expansionist-minded promoters and speculators in Cambridge were based solidly on the assumption that the economic future of Cambridge rested on its potential as a shipping center.” The very name, Cambridgeport, reflected “the expectation that several miles of waterfront could be developed into a port with an intricate system of canals.” In January 1805, Congress designated Cambridge as a “port of delivery” and “canal dredging began [and] prices of dock lots soared." [1] Judge Francis Dana, a lawyer, diplomat, and Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, was one of the primary investors in the development of Cambridgeport. He and his large family lived in a handsome mansion on what is now Dana Hill. Dana lost heavily when Jefferson declared an embargo in 1807. Britain and France objected to America’s commercial relationship with their respective enemies and took steps to curtail trade with the United States. -

Commodore Perry Farm

Th r.r, I C. *. 1 4 7. tj,vi:S t,’J !.&:-r;JO v . I / jL. Lii . ; United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic PAaces ...received lnventory-Nomnation Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries-complete applicable sections 1. Name historic Commodore Perry Farm and/orcommon Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry Birthplace, "The Commodore" 2. Location street & number 184 Post Road - not for publication #2 - Hon. Claudine Schneider city, town South Kings town N ..A vicinity of Cunt.cnoionnl dist4ot state Rhode Island code 44 county Washington code 009 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public i occupied agriculture museum -.JL. buildings .L.. private unoccupied commercial - park structure both work in progress - educational ..._L private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object ?LAJn process ......X yes: restricted government scientific being considered -- yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military other: 4. Owner of Property name Mrs. Wisner Townsend street&number 184 Post Road city, town Wake field PLA.vicinity of state Rhode Island 02880 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Town Clerk, South Kingstown Town i-Jail - street & number 111gb Street city, town Wakefield state Rhode is land 02880 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title See Continuation Sheet #1. has this property been determined eligible? yes ç4ç_ no date - federal .... state county - local depository for survey records city, town state NP Form I0.900.h OMEI No.1074-0018 .‘‘‘‘‘.t3.82 Eq, 1031-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For Nt’S use on’y t’lationa! Register of Historic Places received’ lnventory-Nominatñon Form dateentéred Continuation sheet 1 *, item number , Page 2 Historic American Bui ] clings Survey 1956, 1959 Library of Congress Washington, D.C. -

Mission: History Studiorum Historiam Praemium Est

N a v a l O r d e r o f t h e U n i t e d S t a t e s – S a n F r a n c i s c o C o m m a n d e r y Mission: History Studiorum Historiam Praemium Est Volume 2, Number 1 HHHHHH 3 January 2000 1911: Naval Aviation is Born on San Francisco Bay; Aeroplane Lands on, Takes Off from Pennsylvania Feat Im presses Congress – $25,000 Voted to Develop Navy Aeroplane Program SAN FRANCISCO, Jan. 18, 1911-- Eugene Ely, an aviator in the employ of Glenn H. Curtiss, maker of aeroplanes, today landed a flying machine upon a makeshift platform built on USS Penn- sylvania, which was riding at anchor on San Francisco Bay. After discussing his feat with offi- cials and naval officers on board the armored cruiser, Ely climbed on his aeroplane and calmly took off from the ship, landing safely on Crissy Field at THE LANDING SYSTEM HAD IT ALL. The arresting cables were attached to 50-pound sandbags the Army’s Presidio of San Francisco. which were held off the deck by two longitudinal rails. The C urtiss D-IV airplane had a tailhook — i actually several tailhooks — to snag the cables. At the forward end of the “flight deck,” a canvas Ely’s feat might be called the first barrier was stretched to protect the ship’s superstructure in case the airplane didn’t stop. carrier operation. And though the previ- ous November he took off from a tem- 1944: Japs Splash Pappy – Marine Ace, Wingman porary platform built on the bow of the cruiser USS Birmingham, then in Shot Down over Slot While Leading Raid on Rabaul Hampton Roads, Va., the San Francisco When Marine Corps fighter squad- months later. -

The Provision of Naval Defense in the Early American Republic a Comparison of the U.S

SUBSCRIBE NOW AND RECEIVE CRISIS AND LEVIATHAN* FREE! “The Independent Review does not accept “The Independent Review is pronouncements of government officials nor the excellent.” conventional wisdom at face value.” —GARY BECKER, Noble Laureate —JOHN R. MACARTHUR, Publisher, Harper’s in Economic Sciences Subscribe to The Independent Review and receive a free book of your choice* such as the 25th Anniversary Edition of Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American Government, by Founding Editor Robert Higgs. This quarterly journal, guided by co-editors Christopher J. Coyne, and Michael C. Munger, and Robert M. Whaples offers leading-edge insights on today’s most critical issues in economics, healthcare, education, law, history, political science, philosophy, and sociology. Thought-provoking and educational, The Independent Review is blazing the way toward informed debate! Student? Educator? Journalist? Business or civic leader? Engaged citizen? This journal is for YOU! *Order today for more FREE book options Perfect for students or anyone on the go! The Independent Review is available on mobile devices or tablets: iOS devices, Amazon Kindle Fire, or Android through Magzter. INDEPENDENT INSTITUTE, 100 SWAN WAY, OAKLAND, CA 94621 • 800-927-8733 • [email protected] PROMO CODE IRA1703 The Provision of Naval Defense in the Early American Republic A Comparison of the U.S. Navy and Privateers, 1789–1815 F NICHOLAS J. ROSS he War of 1812 began badly for British ocean-going commerce. Although the United States had a pitifully small navy, it did have a large merchant T marine fleet keen to make a profit. Shortly after the outbreak of the war, the London Times lamented, “American merchant seamen were almost to a man con- verted into privateersmen and the whole of our West India trade either has or will in consequence sustain proportionate loss” (Letters from New York State 1812). -

Open PDF File, 134.33 KB, for Paintings

Massachusetts State House Art and Artifact Collections Paintings SUBJECT ARTIST LOCATION ~A John G. B. Adams Darius Cobb Room 27 Samuel Adams Walter G. Page Governor’s Council Chamber Frank Allen John C. Johansen Floor 3 Corridor Oliver Ames Charles A. Whipple Floor 3 Corridor John Andrew Darius Cobb Governor’s Council Chamber Esther Andrews Jacob Binder Room 189 Edmund Andros Frederick E. Wallace Floor 2 Corridor John Avery John Sanborn Room 116 ~B Gaspar Bacon Jacob Binder Senate Reading Room Nathaniel Banks Daniel Strain Floor 3 Corridor John L. Bates William W. Churchill Floor 3 Corridor Jonathan Belcher Frederick E. Wallace Floor 2 Corridor Richard Bellingham Agnes E. Fletcher Floor 2 Corridor Josiah Benton Walter G. Page Storage Francis Bernard Giovanni B. Troccoli Floor 2 Corridor Thomas Birmingham George Nick Senate Reading Room George Boutwell Frederic P. Vinton Floor 3 Corridor James Bowdoin Edmund C. Tarbell Floor 3 Corridor John Brackett Walter G. Page Floor 3 Corridor Robert Bradford Elmer W. Greene Floor 3 Corridor Simon Bradstreet Unknown artist Floor 2 Corridor George Briggs Walter M. Brackett Floor 3 Corridor Massachusetts State House Art Collection: Inventory of Paintings by Subject John Brooks Jacob Wagner Floor 3 Corridor William M. Bulger Warren and Lucia Prosperi Senate Reading Room Alexander Bullock Horace R. Burdick Floor 3 Corridor Anson Burlingame Unknown artist Room 272 William Burnet John Watson Floor 2 Corridor Benjamin F. Butler Walter Gilman Page Floor 3 Corridor ~C Argeo Paul Cellucci Ronald Sherr Lt. Governor’s Office Henry Childs Moses Wight Room 373 William Claflin James Harvey Young Floor 3 Corridor John Clifford Benoni Irwin Floor 3 Corridor David Cobb Edgar Parker Room 222 Charles C.