Definitional Struggles, Field Assemblages, and Capital Flows: A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

HOW AN ISLAMIC SOLUTION BECAME AN ISLAMIST PROBLEM: EDUCATION, AUTHORITARIANISM AND THE POLITICS OF OPPOSITION IN MOROCCO By ANN MARIE WAINSCOTT A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2013 1 © 2013 Ann Marie Wainscott 2 To Tom and Mary Wainscott 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is hubris to try to acknowledge everyone who contributed to a project of this magnitude; I’m going to try anyway. But first, another sort of acknowledgement is necessary. The parsimonious theories and neat typologies I was taught in graduate school in no way prepared me to understand the tremendous sacrifices and risks of physical and psychological violence that individuals take in authoritarian contexts to participate as members of the political opposition; that is something one learns in the field. I’d like to begin the dissertation by acknowledging my deep respect for those activists, regardless of political persuasion, whose phone calls are recorded and monitored, who are followed every time they leave their homes, who risk their lives and the lives of those they love on behalf of their ideals. For those who have “disappeared,” for those who have endured torture, sometimes for years or decades, for those who are presently in detention, for those whose bodies are dissolved in acid, buried at sea or in mass graves, I acknowledge your sacrifice. I know some of your stories. Although most of my colleagues, interlocutors and friends in Morocco must go unnamed, they ought not go unacknowledged. -

Marruecos Y Su Proyección... Hacia América Latina. / Juan José Vagni

TÍTULO MARRUECOS Y SU PROYECCIÓN HACIA AMÉRICA LATINA A PARTIR DE MOHAMED VI LA GENERACIÓN DE UN ESPACIO ALTERNATIVO DE INTERLOCUCIÓN CON ARGENTINA Y BRASIL AUTOR Juan José Vagni Esta edición electrónica ha sido realizada en 2010 Directora Ana Planet Contreras Curso Máster Universitario en Relaciones Internacionales: Mediterráneo y Mundo Árabe, Iberoamérica y Europa (2007) ISBN 978-84-693-3764-6 © Juan José Vagni © Para esta edición, la Universidad Internacional de Andalucía Universidad Internacional de Andalucía 2010 Reconocimiento-No comercial-Sin obras derivadas 2.5 España. Usted es libre de: • Copiar, distribuir y comunicar públicamente la obra. Bajo las condiciones siguientes: • Reconocimiento. Debe reconocer los créditos de la obra de la manera. especificada por el autor o el licenciador (pero no de una manera que sugiera que tiene su apoyo o apoyan el uso que hace de su obra). • No comercial. No puede utilizar esta obra para fines comerciales. • Sin obras derivadas. No se puede alterar, transformar o generar una obra derivada a partir de esta obra. • Al reutilizar o distribuir la obra, tiene que dejar bien claro los términos de la licencia de esta obra. • Alguna de estas condiciones puede no aplicarse si se obtiene el permiso del titular de los derechos de autor. • Nada en esta licencia menoscaba o restringe los derechos morales del autor. Universidad Internacional de Andalucía 2010 Universidad Internacional de Andalucía Sede Iberoamericana Santa María de La Rábida Master Universitario en Relaciones Internacionales: Mediterráneo y Mundo Árabe, Iberoamérica y Europa TESINA MARRUECOS Y SU PROYECCIÓN HACIA AMÉRICA LATINA A PARTIR DE MOHAMED VI: la generación de un espacio alternativo de interlocución con Argentina y Brasil Autor: Juan José Vagni Director: Dra. -

Marokkos Neue Regierung: Premierminister Abbas El Fassi Startet Mit Einem Deutlich Jüngeren Und Weiblicheren Kabinett

Marokkos neue Regierung: Premierminister Abbas El Fassi startet mit einem deutlich jüngeren und weiblicheren Kabinett Hajo Lanz, Büro Marokko • Die Regierungsbildung in Marokko gestaltete sich schwieriger als zunächst erwartet • Durch das Ausscheiden des Mouvement Populaire aus der früheren Koalition verfügt der Premierminister über keine stabile Mehrheit • Die USFP wird wiederum der Regierung angehören • Das neue Kabinett ist das vermutlich jüngste, in jedem Fall aber weiblichste in der Geschichte des Landes Am 15. Oktober 2007 wurde die neue ma- Was fehlte, war eigentlich nur noch die rokkanische Regierung durch König Mo- Verständigung darauf, wie diese „Re- hamed VI. vereidigt. Zuvor hatten sich die Justierung“ der Regierungszusammenset- Verhandlungen des am 19. September vom zung konkret aussehen sollte. Und genau König ernannten und mit der Regierungs- da gingen die einzelnen Auffassungen doch bildung beauftragten Premierministers Ab- weit auseinander bzw. aneinander vorbei. bas El Fassi als weitaus schwieriger und zä- her gestaltet, als dies zunächst zu erwarten Für den größten Gewinner der Wahlen vom gewesen war. Denn die Grundvorausset- 7. September, Premierminister El Fassi und zungen sind alles andere als schlecht gewe- seiner Istiqlal, stand nie außer Zweifel, die sen: Die Protagonisten und maßgeblichen Zusammenarbeit mit dem größten Wahlver- Träger der letzten Koalitionsregierung (Istiq- lierer, der sozialistischen USFP unter Füh- lal, USFP, PPS, RNI, MP) waren sich einig rung von Mohamed Elyazghi, fortführen zu darüber, die gemeinsame Arbeit, wenn wollen. Nur die USFP selbst war sich da in auch unter neuer Führung und eventuell nicht so einig: Während die Basis den Weg neuer Gewichtung der Portfolios, fortfüh- die Opposition („Diktat der Urne“) präfe- ren zu wollen. -

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project Labor Series

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project Labor Series JAMES MATTSON Interviewed by: Don Kienzle Initial interview date: May 4, 1995 Copyright 2020 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born in Minneapolis, Minnesota BA in Political Science, Language, Gustavus Adolphus College ~1949–~1956 Service in Korean War ~1950–~1953 Fellowship at College of Europe 1956–1957 Entered the Foreign Service 1957 Vienna, Austria—Consular Officer 1957–1958 Salzburg, Austria—Consular Officer 1958–1959 Hungarian Refugee Visa Program Bonn, Germany—Local Consular Officer 1959–1960 First Experience with Labor Attachés Richard Eldridge Washington, D.C., U.S.A.—INR, French Desk 1960–1962 Casablanca, Morocco—Consular Officer, Consular General 1962–1964 Closing Air Bases in Morocco Tangier, Morocco—Language Training 1964–1966 Washington, D.C.—Labor Training 1966–1966 Casablanca, Morocco—Labor Attaché 1966–1969 Major Labor Federations 1 Moroccan, Tunisian, and Algerian Labor Movement Morocco and the IFCTU Contact Meetings USIS Program Abdallah Ibrahim Conference in Beirut 1965 Riots in Casablanca French News Reaction to the Six Day War CODEL Visits Washington, D.C.—INR, North African Affairs 1969–1971 Washington, D.C.—USAID 1971–1973 Beirut, Lebanon—Regional Labor Attaché 1973–1975 Dialects of Arabic Labor Assistant Habib Haddad Private Sector Wage Increases Trade Unions European Model vs. Lebanese Model Lebanese Civil War Regional Travels Family Evacuation Twenty-four Hour a Day Curfew Washington, D.C.—FSI, Economics Training 1976–1976 Washington, D.C.—NEA/RA, Regional Labor Attaché 1976–1980 Travel Chinese-built Textile Plant Palestinian Refugees Annual ILO Conference U.S. Withdrawal from the ILO Brussels, Belgium—Regional Labor Attaché 1980–1983 Vredeling Draft Solidarnosc Nigerian Minister of Labor Turkey and the European Community North-South Issues 2 European Trade Union Confederation Processing of Draft Directives U.S. -

Les Gouvernements Marocains Depuis L'indépendance (Chronologie)

Les gouvernements marocains depuis l'Indépendance (Chronologie) - 1er gouvernement, Si Bekkai Ben M'barek Lahbil, président du conseil (7 décembre 1955). - 2ème gouvernement, Si Bekkai Ben M'barek Lahbil, président du conseil (28 octobre 1956). - 3ème gouvernement, Haj Ahmed Balafrej, président du conseil et ministre des affaires étrangères (12 mai 1958). - 4ème gouvernement, M. Abdallah Ibrahim, président du conseil et ministre des Affaires étrangères (24 décembre 1958). - 5ème gouvernement, Feu SM Mohammed V, président du conseil, SAR le Prince héritier Moulay Hassan, vice-président du conseil et ministre de la Défense nationale (27 mai 1960). - 6ème gouvernement, Feu SM Hassan II, président du conseil, ministre de la Défense nationale et ministre de l'Agriculture (4 mars 1961). - 7ème gouvernement, Feu SM Hassan II, président du conseil et ministre des Affaires étrangères (2 juin 1961). - 8ème gouvernement, pas de Premier ministre, Haj Ahmed Balafrej, représentant personnel de SM le Roi et ministre des Affaires étrangères (5 janvier 1963). - 9ème gouvernement, M. Ahmed Bahnini, président du conseil (13 novembre 1963). - 10ème gouvernement, Feu SM Hassan II, président du conseil (8 juin 1965). - 11ème gouvernement, Dr. Mohamed Benhima, Premier ministre (11 novembre 1967), Dr. Ahmed Laraki, Premier Ministre à partir du 7 octobre 1969. - 12ème gouvernement, M. Mohamed Karim Lamrani, Premier ministre (6 août 1971). - 13ème gouvernement, M. Mohamed Karim Lamrani, Premier ministre (12 avril 1972). - 14ème gouvernement, M. Ahmed Osman, Premier ministre (20 novembre 1972). - 15ème gouvernement, M. Ahmed Osman, Premier ministre (25 avril 1974). - 16ème gouvernement, M. Ahmed Osman, Premier ministre (10 octobre 1977). - 17ème gouvernement, M. Maati Bouabid, Premier ministre et ministre de la Justice (27 mars 1979). -

AFFAIRE BEN BARKA : LE POINT DE VUE DES SERVICES DE RENSEIGNEMENT Gérald Arboit

AFFAIRE BEN BARKA : LE POINT DE VUE DES SERVICES DE RENSEIGNEMENT Gérald Arboit To cite this version: Gérald Arboit. AFFAIRE BEN BARKA : LE POINT DE VUE DES SERVICES DE RENSEIGNE- MENT. 2015. hal-01152723 HAL Id: hal-01152723 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01152723 Submitted on 18 May 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License Centre Français de Recherche sur le Renseignement NOTE HISTORIQUE N°43 AFFAIRE BEN BARKA : LE POINT DE VUE DES SERVICES DE RENSEIGNEMENT Gérald Arboit Aborder l’Affaire Ben Barka du point de vue des services de renseignement revient à délaisser les interrogations et les suspicions de la querelle politicienne, dans laquelle l’Affaire s’est enferrée depuis la pantalonnade des deux procès de 1966 et 1967. De cette analyse, reposant sur l’abondante bibliographie publiée1 et quelques documents d’archives provenant des services français2 et américains3, le mystère politique ne sera certainement pas levé. Toutefois, l’Affaire sera rétablie dans son double contexte géopolitique. La disparition du dirigeant révolutionnaire internationaliste El Medhi Ben Barka doit en effet être replacée dans son époque, à savoir le Maroc des lendemains de l’indépendance et de l’accession d’Hassan II au trône. -

THE AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE 30 Rue La Boetie Paris 8, Prance

THE AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE 30 Rue La Boetie Paris 8, Prance April 9, 1959 MEMORANDUM TO: New York Office PROM: Abraham Karlikow, Paris Office SUBJ: Situation of the Jewish Community in Morocco This report is based on a five-day visit to Morocco at the end of March. It deals with the following subjects: The general situation in Morocco; Its effects on the Jewish population; Jewish community and welfare institutions and attempts at "integration"; Jewish attitudes toward the long-range future; The Moroccan government and Jewish emigration; Jewish refugees in Tangiers. The general situation in Morocco Politically and economically Morocco is in a state of flux and effervescence. The political upheaval is due to a fight which has riven Istiqlal, the leading and now virtually only important political party in Morocco* On the one hand, there is the more conservative and. traditional wing of the Istiqlal headed by former Moroccan premier Ahmed Balafrej and by the leading ideologist of the party, Allal El Passi; on the other, the more Jacobin wing led by the present premier Abdallah Ibrahim and Mehdi Ben Barka, president of the Consultative Assembly, The strength of the latter group is concentrated in the Moroccan trade unions and in the cities; that of the former group among the middle classes and the traditionalists in the Moroccan hinterland. Both groups are going at each other hammer and tongs. Neither, apparently, feels strong enough to force matters to a showdown at present. In some respects, therefore, their conflict takes on the aspects of a super-heated election campaign — as it may well be, finally, since preparations are being made to hold Morocco's first elections before the end of the year. -

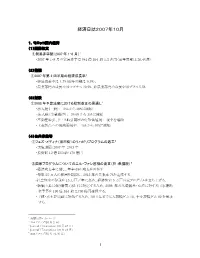

Keizainisshi 2007-10

経済日誌2007年10月 1.モロッコ国内経済 (1)国際収支 ①貿易赤字額(2007 年 1-8 月)1 ・2007年1-8月の貿易赤字は 841 億 DH=約 1.2 兆円(前年同期比 26.4%増) (2)指標 ①2007 年第 2 四半期の経済成長率2 ・経済成長率は 1.7%(前年同期は 9.3%)。 ・農業部門の成長率はマイナス 20.9%、非農業部門の成長率はプラス 5.5% (3)財政 ①2008 年予算法案における税制改正の見通し3 ・法人税(一般): 35% から 30%に減額 ・法人税(金融関連): 39.6% から 35%に減額 ・不動産取引、リース取引関連の付加価値税: 税率を増額 ・工業製品への最高関税率: 45% から 40%に減額 (4)公共事業等 ①フェズ・メディナ(旧市街)のリハビリプログラムの着工4 ・実施期間:2007 年-2013 年 ・投資額12億DH=約170億円 ②国家プログラムについてのエル・ファシ首相の発言(於:衆議院)5 ・経済成長率に関し、年率 6%の成長を目指す ・毎年 25 万人の雇用を創設し、2012 年の失業率 7%を達成する。 ・社会住宅の建設を 15 万戸/年に高め、経済住宅 5 万戸国家プログラムを立ち上げる。 ・物価上昇に伴う購買力低下に対応するため、2008 年の基礎製品・石油に対する国家補助 金予算を 190 億 DH=約 2,700 億円確保する。 ・干魃・水不足問題に対処するため、2012 年までに大規模ダム 10、中小規模ダム 60 を建設 する。 1 為替局ホームページ 2 エコノマップ(10月1日) 3 Journal l’Economiste (10 月 25 日) 4 Journal l’Economiste (10 月 24 日) 5 エコノマップ(10 月 25,26 日) 1 ・今後5年間で、ホテルのベッド数を15万床から 26.5 万床に高め、8 万人の雇用を創設す る。観光収入を 600 億 DH から 900 億 DH(2012 年)=約 1.3 兆円まで高める ・高速道路建設第2次計画(380km の増設)を立ち上げる(都市 Beni Mellal を高速道路網に 組み入れる。ラバト~カサブランカ間の輸送能力増強。El Jadida-Safi 区間の建設)。 ・地中海道路(Tanger - Saidia 間)の 2011 年開通 ・地方道路整備計画に関し、道路整備を年 1,500km/年から 2,000km/年に加速し、2012 年 における地方住民の地方道路へのアクセス率を 80%に高める。 ・タンジェ~カサブランカ間高速鉄道(TGV)の第1区間工事を2009年に着工する。 (5)産業 ①国営製鉄会社(SONASID)の2007年上半期業績6 ・上半期売上高は 32.6 億 DH=約 450 億円(前年同期比 20.6%増) ・上半期利益は 4.94 億 DH=約 70 億円(前年同期比 52%増) ・SONASID 社は、2006年にArcelor/Mittal社とパートナーシップ協定を締結している。 (6)その他 ①カサブランカに北アフリカ最大のショッピングモールを建設する計画7 ・衣類流通業の Aksal 社と Nesk Investment 社の合弁会社が、総工費 20 億 DH=約 280 億円をかけ、10 ヘクタールの敷地に「モロッコ・モール」を建設 ・ファッション、宝飾などの 200 以上の国内、海外ブランドが出店、大型スーパーマーケット、 レストラン、3D ムービー・シアター、スポーツクラブ、5000 台収容の駐車場などが設置され る予定。 ②モロッコ人民銀行グループ(Le -

North Africa: Non-Islamic Opposition Movements

WRITENET Paper No. 11/2002 NORTH AFRICA: NON-ISLAMIC OPPOSITION MOVEMENTS George Joffé Independent Researcher, UK September 2002 WriteNet is a Network of Researchers and Writers on Human Rights, Forced Migration, Ethnic and Political Conflict WriteNet is a Subsidiary of Practical Management (UK) E-mail: [email protected] THIS PAPER WAS PREPARED MAINLY ON THE BASIS OF PUBLICLY AVAILABLE INFORMATION, ANALYSIS AND COMMENT. ALL SOURCES ARE CITED. THE PAPER IS NOT, AND DOES NOT PURPORT TO BE, EITHER EXHAUSTIVE WITH REGARD TO CONDITIONS IN THE COUNTRY SURVEYED, OR CONCLUSIVE AS TO THE MERITS OF ANY PARTICULAR CLAIM TO REFUGEE STATUS OR ASYLUM. THE VIEWS EXPRESSED IN THE PAPER ARE THOSE OF THE AUTHOR AND ARE NOT NECESSARILY THOSE OF WRITENET OR UNHCR. ISSN 1020-8429 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction........................................................................................1 1.1 The Nature of Opposition............................................................................1 1.2 Regime and Opposition ...............................................................................2 1.3 Leadership and Political Culture ...............................................................3 1.4 The Alternatives...........................................................................................5 1.5 The Future ....................................................................................................6 2 Opposition Political Parties in North Africa ...................................7 2.1 Egypt .............................................................................................................7 -

El PODER EJECUTIVO EN MARRUECOS EN LA CONSTITUCIÓN DE 2011

ADVERTIMENT. Lʼaccés als continguts dʼaquesta tesi queda condicionat a lʼacceptació de les condicions dʼús establertes per la següent llicència Creative Commons: http://cat.creativecommons.org/?page_id=184 ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis queda condicionado a la aceptación de las condiciones de uso establecidas por la siguiente licencia Creative Commons: http://es.creativecommons.org/blog/licencias/ WARNING. The access to the contents of this doctoral thesis it is limited to the acceptance of the use conditions set by the following Creative Commons license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/?lang=en Tesis Doctoral El PODER EJECUTIVO EN MARRUECOS EN LA CONSTITUCIÓN DE 2011. Transformación y desarrollo del poder ejecutivo tradicional del jefe del Estado y del nuevo jefe de Gobierno ABDESSAMAD HALMI BERRABAH Director: Dr. ANTONI ROIG BATALLA Programa de Doctorado en Derecho (RD 99/2011) Doctorado en Derecho Constitucional Departamento de Ciencias Políticas y de Derecho Público FACULTAD DE DERECHO Diciembre, 2017 1 AGRADECIMIENTOS El presente trabajo de investigación no hubiera sido el mismo sin la colaboración de personas, instituciones y centros de investigación en España y Marruecos por igual. Deseamos manifestar a todos ellos, ya desde este momento, nuestro agradecimiento y esperamos que nos disculpen cuantos se quedan sin mencionar. También deseamos manifestar nuestro agradecimiento a todas mis profesoras y profesores en la UAB, por su magisterio profesional y personal a la hora de encaminarme bajo su certera guía en los pasos dados en mi vida universitaria en Barcelona. Los fondos bibliográficos de distintas fundaciones y universidades, entre los que destacamos los de las Universidades UAB (Esp), Universidad Rovira i Virgili (Tarr. -

Ellen Lust-Okar Source: Comparative Politics, Vol

Divided They Rule: The Management and Manipulation of Political Opposition Author(s): Ellen Lust-Okar Source: Comparative Politics, Vol. 36, No. 2 (Jan., 2004), pp. 159-179 Published by: Ph.D. Program in Political Science of the City University of New York Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4150141 Accessed: 24/07/2009 16:28 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=phd. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Ph.D. Program in Political Science of the City University of New York is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Comparative Politics. -

La Posición De La Corona En La Constitución Y Su Papel En El

MOHAMED CHEKRAD (Universidad de Valencia) La posición de la Corona en la Constitución 1 y su papel en el sistema político marroquí 1. INTRODUCCION Desde los años noventa, Marruecos ha estado viviendo cambios que han incidido e incidirán de manera decisiva en su futuro; importantes ajustes políticos e institucionales que podrían desembocar en una transición a la democracia o, por el contrario, toparse con dificultades y abocar al país a procesos de recesión. En este escenario, los modelos occidentales –tanto los políticos y económicos como los sociales–, han entrado en contacto con identidades y valores arraigados en la cultura política, económica y social de base familiar y comunitaria que caracteriza a las sociedades árabes en general y, a la de Marruecos en particular. Si por un lado los desequilibrios y las desigualdades internas, así como las carencias en múltiples ámbitos, colocan a Maruecos en una posición débil en cuanto a su nivel de desarrollo, por otro lado los procesos de cambio iniciados en estos últimos años, así como el incremento de las relaciones sociales y económicas debidas a las migraciones, las inversiones y los acuerdos internacionales son cada día más importantes como lo son, en especial, las demandas y las actuaciones de la sociedad civil. ¿Hay algo más herético que leer el sistema político marroquí a través de una clave modernista, referida a los cánones de la democracia liberal? Por el contrario, ¿hay algo más restrictivo que aprehenderlo en función del enfoque tradicionalista, que prefigura los fundamentos originarios arabo-musulmán? Asociar en una misma reflexión estos dos valores referenciales no es una vía metodológica intermedia, ni tampoco una simple formula para encontrar una 1 El presente texto constituye una versión resumida, actualizada y adaptada del Capítulo V de la tesis doctoral que, con el título «Monarquía y transición a la democracia: un estudio comparado de los casos español y marroquí», y bajo la dirección del Prof.