R01783 0.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monographie Regionale Beni Mellal-Khenifra 2017

Royaume du Maroc المملكة المغربية Haut-Commissariat au المندوبية السامية للتخطيط Plan MONOGRAPHIE REGIONALE BENI MELLAL-KHENIFRA 2017 Direction régionale Béni Mellal-Khénifra Table des matières INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 8 PRINCIPAUX TRAITS DE LA REGION BENI MELLAL- KHENIFRA ................. 10 CHAPITRE I : MILIEU NATUREL ET DECOUPAGE ADMINISTRATIF ............ 15 1. MILIEU NATUREL ................................................................................................... 16 1.1. Reliefs ....................................................................................................................... 16 1.2. Climat ....................................................................................................................... 18 2. Découpage administratif ............................................................................................ 19 CHAPITRE II : CARACTERISTIQUES DEMOGRAPHIQUES DE LA POPULATION ........................................................................................................................ 22 1. Population ................................................................................................................... 23 1.1. Evolution et répartition spatiale de la population .................................................. 23 1.2. Densité de la population .......................................................................................... 26 1.3. Urbanisation ........................................................................................................... -

Or Download the Full Issue Here

From Soulard’s Notebooks Assistant Editor: Kassandra Soulard Feedback................................................................................................................................1 Poetry by Joe Ciccone.............................................................................................................3 Same Moon Shining [Memoir Excerpts] by Tamara Miles.........................................................................................................11 Many Musics [Poetry] by Raymond Soulard, Jr. ......................................................................................17 Psychedelic Summercamp [Travel Journal] by Nathan D. Horowitz.............................................................................................29 Poetry by Ace Boggess...........................................................................................................37 Sapphire Sins [Travel Journal] by Charlie Beyer.........................................................................................................41 Poetry by Colin James..........................................................................................................53 Notes from New England [Commentary] by Raymond Soulard, Jr. ......................................................................................57 Poetry by Judih Haggai.........................................................................................................63 Notes on Fate Versus Free Will by Jimmy Heffernan..................................................................................................67 -

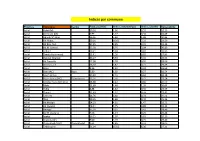

Indices Par Commune

Indices par commune Province Commune Centre Taux_pauvreté indice_volumétrique indice_séverité Vulnérabilité Azilal Azilal (M) 10,26 1,96 0,55 19,23 Azilal Demnate (M) 6,99 1,27 0,34 16,09 Azilal Agoudi N'Lkhair 26,36 5,84 1,88 30,84 Azilal Ait Abbas 50,01 16,62 7,33 23,59 Azilal Ait Bou Oulli 37,95 9,65 3,45 31,35 Azilal Ait M'Hamed 35,58 8,76 3,04 30,80 Azilal Tabant 19,21 3,24 0,81 33,95 Azilal Tamda Noumercid 15,41 2,90 0,82 27,83 Azilal Zaouiat Ahansal 35,27 9,33 3,45 28,53 Azilal Ait Taguella 17,08 3,28 0,95 28,09 Azilal Bni Hassane 16,10 2,87 0,77 29,55 Azilal Bzou 8,56 1,32 0,32 24,68 Azilal Bzou (AC) Bzou 5,80 1,02 0,27 16,54 Azilal Foum Jemaa 15,22 2,51 0,62 31,18 Azilal Foum Jemaa (AC) Foum Jemaa 13,26 2,56 0,72 22,54 Azilal Moulay Aissa Ben Driss 13,38 2,42 0,66 26,59 Azilal Rfala 21,69 4,46 1,35 30,64 Azilal Tabia 8,88 1,42 0,35 23,59 Azilal Tanant 11,63 2,12 0,59 23,41 Azilal Taounza 13,76 2,60 0,74 25,52 Azilal Tisqi 10,35 1,66 0,40 25,26 Azilal Ait Mazigh 24,23 4,91 1,47 33,72 Azilal Ait Ouqabli 18,31 3,25 0,88 33,12 Azilal Anergui 35,18 9,25 3,41 28,49 Azilal Bin El Ouidane 7,96 1,14 0,25 25,44 Azilal Isseksi 16,21 2,97 0,81 29,19 Azilal Ouaouizeght 9,00 1,19 0,25 29,46 Azilal Ouaouizeght (AC) Ouaouizeght 9,61 1,85 0,52 18,05 Azilal Tabaroucht 51,04 15,52 6,36 27,11 Province Commune Centre Taux_pauvreté indice_volumétrique indice_séverité Vulnérabilité Azilal Tagleft 27,66 6,89 2,44 26,89 Azilal Tiffert N'Ait Hamza 16,84 3,99 1,37 21,90 Azilal Tilougguite 24,10 5,32 1,70 30,13 Azilal Afourar 5,73 0,80 0,17 20,51 Azilal -

Microbiological Survey of the Bathing Water of Moroccan Beaches From

International Multispecialty Journal of Health (IMJH) ISSN: [2395-6291] [Vol-4, Issue-5, May- 2018] Microbiological survey of the bathing water of moroccan beaches from Mehdia to Skhirat EL MIMOUNI Naîm1§, AIT CHATTOU El Mustafa2, BOUAYYADI Abdellatif3, HACHI Touria4, OUNINE Khadija5 1,5Laboratory of Biology and Health, Faculty of Sciences, Ibn Tofail University, Kenitra, Morocco 2Chief of Regional Center of National Institute of Fisheries, Dakhla, Marocco 3,4Laboratory of Biotechnology and Environment, Faculty of Sciences Kenitra, Morocco §Corresponding author's Email: [email protected] Abstract—The Moroccan coastline occupies a privileged place at the level of the entire coastline of the African continent. The quality of bathing water is a criterion increasingly demanded by the general public for the choice of its holiday resorts. Main objective of this present study is to find out the status of to find status of bathing water through physicochemical and microbiological examination. Sampling was done from 8 beaches of Kenitra Mehdia, Nations, Rabat-Sale, Harhoura, Temara, Golden Sand, Val D'or and the beach of Skhirate Amphitrite. Bacteriological evaluations were done & presence of feacal Coliforms and/or Streptococci was considered as indicative of faecal pollution. Enumeration of faecal Coliforms and faecal Streptococci was done by filter membrane method on nutrient media Tergitol7 Agar, Litskey, Slanetz & Bartley. In addition to microbiological sampling of water, temperature and pH of the water were measured "in situ". Data related to the tide (high or low) and populations were collected. Regarding bacterial load of beaches in present study it was found that at Mehdia beach, Nations beach, Rabat-Sale beach, Temara beach, Harhoura beach, Sable D’or beach and at Skhirat beach the contamination standard is exceeded in 30% of samples for CF and 20% for SF, 10% for CF and 0% for SF, 100% of the samples for CF and 70% for SF, 50% for CF and in none (0%) for SF, 20% for CF and 10% for SF, 30% for CF and 10% for SF and 40% for CF and 10% for SF respectively. -

Produits De Terroir Phares Dans La Région De Rabat-Salé-Kénitra Produits De Terroir Dans La Région De Rabat-Salé-Kénitra

Produits de Terroir phares dans la Région de Rabat-Salé-Kénitra Produits de Terroir dans la Région de Rabat-Salé-Kénitra A la découverte des PRODUITS DE TERROIR RÉGION de notre Arachide Coriandre Miel d'Eucalyptus Trues Camomille de la Maâmora Miel d'oranger Cactus S'houl Raisins Muscat Race bovine de Skhirat Miel d’Oulmes Zaer Citrouille Toutes eurs de Maaziz Haricots verts de Skhirat Lavandin d’Oulmès Lentille de Zaer 2 Produits de Terroir dans la Région de Rabat-Salé-Kénitra A la découverte des PRODUITS DE TERROIR RÉGION de notre Arachide Coriandre Miel d'Eucalyptus Trues Camomille de la Maâmora Miel d'oranger Cactus S'houl Raisins Muscat Race bovine de Skhirat Miel d’Oulmes Zaer Citrouille Toutes eurs de Maaziz Haricots verts de Skhirat Lavandin d’Oulmès Lentille de Zaer 3 2 catalogue final SIAM 2018.- version corrigée le 16 avril 2018.pdf 1 19/04/2018 10:16 Produits de Terroir dans la Région de Rabat-Salé-Kénitra ujourd’hui, plus que jamais, les consommateurs manifestent A un engouement grandissant pour les produits de terroir dits «authentiques». Parce qu’ils sont naturels et sains, ils connaissent un grand succès, localement et même à l’étranger. A travers ce livret, nous vous proposons de découvrir une large palette des produits de terroir de notre Région. Bienvenue dans la Région de Rabat Vous y découvrirez également des différents goûts et saveurs, Salé-Kénitra fruit d’un savoir faire ancestral, atypique et d’une géographie très spécifique. Ce livret, largement documenté, met à votre disposition toutes les informations nécessaires sur les produits de notre région Nous vous souhaitons une bonne découverte. -

National Retailer & Restaurant Expansion Guide Spring 2016

National Retailer & Restaurant Expansion Guide Spring 2016 Retailer Expansion Guide Spring 2016 National Retailer & Restaurant Expansion Guide Spring 2016 >> CLICK BELOW TO JUMP TO SECTION DISCOUNTER/ APPAREL BEAUTY SUPPLIES DOLLAR STORE OFFICE SUPPLIES SPORTING GOODS SUPERMARKET/ ACTIVE BEVERAGES DRUGSTORE PET/FARM GROCERY/ SPORTSWEAR HYPERMARKET CHILDREN’S BOOKS ENTERTAINMENT RESTAURANT BAKERY/BAGELS/ FINANCIAL FAMILY CARDS/GIFTS BREAKFAST/CAFE/ SERVICES DONUTS MEN’S CELLULAR HEALTH/ COFFEE/TEA FITNESS/NUTRITION SHOES CONSIGNMENT/ HOME RELATED FAST FOOD PAWN/THRIFT SPECIALTY CONSUMER FURNITURE/ FOOD/BEVERAGE ELECTRONICS FURNISHINGS SPECIALTY CONVENIENCE STORE/ FAMILY WOMEN’S GAS STATIONS HARDWARE CRAFTS/HOBBIES/ AUTOMOTIVE JEWELRY WITH LIQUOR TOYS BEAUTY SALONS/ DEPARTMENT MISCELLANEOUS SPAS STORE RETAIL 2 Retailer Expansion Guide Spring 2016 APPAREL: ACTIVE SPORTSWEAR 2016 2017 CURRENT PROJECTED PROJECTED MINMUM MAXIMUM RETAILER STORES STORES IN STORES IN SQUARE SQUARE SUMMARY OF EXPANSION 12 MONTHS 12 MONTHS FEET FEET Athleta 46 23 46 4,000 5,000 Nationally Bikini Village 51 2 4 1,400 1,600 Nationally Billabong 29 5 10 2,500 3,500 West Body & beach 10 1 2 1,300 1,800 Nationally Champs Sports 536 1 2 2,500 5,400 Nationally Change of Scandinavia 15 1 2 1,200 1,800 Nationally City Gear 130 15 15 4,000 5,000 Midwest, South D-TOX.com 7 2 4 1,200 1,700 Nationally Empire 8 2 4 8,000 10,000 Nationally Everything But Water 72 2 4 1,000 5,000 Nationally Free People 86 1 2 2,500 3,000 Nationally Fresh Produce Sportswear 37 5 10 2,000 3,000 CA -

Casablanca - New York Times

Casablanca - New York Times http://travel.nytimes.com/2006/04/16/travel/16going.html?pagewant... April 16, 2006 GOING TO Casablanca By SETH SHERWOOD WHY GO NOW Thanks to a certain Hollywood film, this Moroccan port city forever recalls the black-and-white era of foggy steamships and fedora hats. It's the author and aviator Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, strolling Paris-style streets on a stopover to Dakar. It's Edith Piaf, holed up in a hotel with her lover, the prizefighter Marcel Cerdan. It's Josephine Baker, crooning "J'ai Deux Amours" at the Art Deco Rialto theater. And, ultimately, it's Humphrey Bogart, telling Ingrid Bergman that the problems of three little people don't amount to a hill of beans in this crazy world. But truth be told, the glamour wore off a long time ago. With its majestically faded architecture and dusty colonial boulevards, this rough-edged metropolis of four million feels like a fossil of bygone days, which is exactly what makes Casablanca so enticing. Its raffish air and melancholy grandeur — more evocative of Havana than Hong Kong — are the rare exception to a shrinking, touristy world of design-minded boutique hotels and Wallpaper-style homogeneity. These days, the grandiose architecture concocted by the French colonialists — sinewy Art Nouveau edifices, cool Art Deco town houses, collagelike Neo-Moorish palaces — has made the city a giant museum. Under the eye of the world's tallest minaret, men and women still walk along the palm-lined medinas in hooded djellaba robes and head-covering hijab. And with the exception of Casablanca's thoroughly contemporary night life, the newest hot spots exploit the city's aging bones, resurrecting venerable structures into period boutiques and cafes. -

Cadastre Des Autorisations TPV Page 1 De

Cadastre des autorisations TPV N° N° DATE DE ORIGINE BENEFICIAIRE AUTORISATIO CATEGORIE SERIE ITINERAIRE POINT DEPART POINT DESTINATION DOSSIER SEANCE CT D'AGREMENT N Casablanca - Beni Mellal et retour par Ben Ahmed - Kouribga - Oued Les Héritiers de feu FATHI Mohamed et FATHI Casablanca Beni Mellal 1 V 161 27/04/2006 Transaction 2 A Zem - Boujad Kasbah Tadla Rabia Boujad Casablanca Lundi : Boujaad - Casablanca 1- Oujda - Ahfir - Berkane - Saf Saf - Mellilia Mellilia 2- Oujda - Les Mines de Sidi Sidi Boubker 13 V Les Héritiers de feu MOUMEN Hadj Hmida 902 18/09/2003 Succession 2 A Oujda Boubker Saidia 3- Oujda La plage de Saidia Nador 4- Oujda - Nador 19 V MM. EL IDRISSI Omar et Driss 868 06/07/2005 Transaction 2 et 3 B Casablanca - Souks Casablanca 23 V M. EL HADAD Brahim Ben Mohamed 517 03/07/1974 Succession 2 et 3 A Safi - Souks Safi Mme. Khaddouj Bent Salah 2/24, SALEK Mina 26 V 8/24, et SALEK Jamal Eddine 2/24, EL 55 08/06/1983 Transaction 2 A Casablanca - Settat Casablanca Settat MOUTTAKI Bouchaib et Mustapha 12/24 29 V MM. Les Héritiers de feu EL KAICH Abdelkrim 173 16/02/1988 Succession 3 A Casablanca - Souks Casablanca Fès - Meknès Meknès - Mernissa Meknès - Ghafsai Aouicha Bent Mohamed - LAMBRABET née Fès 30 V 219 27/07/1995 Attribution 2 A Meknès - Sefrou Meknès LABBACI Fatiha et LABBACI Yamina Meknès Meknès - Taza Meknès - Tétouan Meknès - Oujda 31 V M. EL HILALI Abdelahak Ben Mohamed 136 19/09/1972 Attribution A Casablanca - Souks Casablanca 31 V M. -

L'ambitiond'andre Azoulay Sanbar, Le Responsable De

Quand leMaroc sera islamiste Lacorruption, unsport national L'ambitiond'Andre Azoulay I'Equipement et wali de Marrakech, qui sera nomme en 200S wali de Tanger; le polytechnicien Driss Benhima, fils Durant les deux dernieres annees du regne d'Hassan II, d'un ancien Premier ministre et ministre de I'Interieur ; un vent reformateur va souffler pendant quelques mois au Mourad Cherif, qui fut plusieurs fois ministre et dirigea Maroc. Un des principaux artisans de cette volonte de tour atour l'Omnium nord-africain puis l'Office cherifien changement aura ete Andre Azoulay, le premier juif maro des phosphates - les deux neurons economiques du cain aetre nomme conseiller de SaMajeste par dahir (decret royaume -, avant d'etre nomme en mars 2006 ala tete de royal). Le parcours militant de ce Franco-Marocain, un la filiale de BNPParibas au Maroc, la BMCI ; et enfin Hassan ancien de Paribas et d'Eurocom, temoigne d'un incontes Abouyoub, plusieurs fois ministre et ancien ambassadeur. table esprit d'ouverture. Artisan constant d'un rapproche Ainsi Andre Azoulay pretendait, avec une telle garde ment [udeo-arabe, il cree en 1973 l'association Identite et rapprochee, aider le roi Hassan II dans ses velleites Dialogue alors qu'il reside encore en France. Aidepar Albert reformatrices. Sasson, un ancien doyen de la faculte de Rabat fort res Seulement, l'essai n'a pas ete transforme. Dans un pre pecte, Andre Azoulay organise de multiples rencontres mier temps, l'incontestable ouverture politique du entre juifs et Arabes.Sesliens d'amitie avec Issam Sartaoui, royaume, qui a vu Hassan II nommer ala tete du gouverne Ie responsable de l'OLP assassine en 1983, ou avec Elias ment le leader socialiste de l'USFP, s'est accompagnee d'un Sanbar, le responsable de la Revue d'etudes palestiniennes, processus d'assainissement economique. -

Governance and Representation in the Afghan Urban Transition

Afghanistan’s Constitution Ten Years On: What Are the Issues? Mohammad Hashim Kamali August 2014 Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit Issues Paper Afghanistan’s Constitution Ten Years On: What Are the Issues? Mohammad Hashim Kamali August 2014 Funding for this research was provided by the United States Institute of Peace and the Embassy of Finland. 2014 Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit Cover photo: (From top to bottom): A view of the 2004 constitutional Loya Jirga Sessions; people’s representatives gesture during 2004 constitutional Loya Jirga; people’s representatives listening to a speech during 2004 constitutional Loya Jirga; Loya Jirga members during the 2004 Constitutional Loya Jirga, Kabul (by National Archives of Afghanistan). AREU wishes to thank the National Archives of Afghanistan for generously granting access to its photo collection from the 2004 Constitutional Loya Jirga. Layout: Ahmad Sear Alamyar AREU Publication Code: 1416E © 2014 Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of AREU. Some rights are reserved. This publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted only for non- commercial purposes and with written credit to AREU and the author. Where this publication is reproduced, stored or transmitted electronically, a link to AREU’s website (www.areu.org.af) should be provided. Any use of this publication falling outside of these permissions requires prior written permission of the publisher, the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit. Permission can be sought by emailing [email protected] or by calling +93 (0) 799 608 548. -

The Case of Morocco

Democracy Promotion in the European Neighbourhood Policy the case of Morocco Author: Helena Bergé Supervised by: Hubert Smekal, Ph.D. Masaryk University 2012-2013 ABSTRACT Contrary to European Union (EU) rhetoric on the importance of democracy promotion, security considerations have always been prioritised over democratisation in its relations with the Southern Mediterranean. In a review of the European Neighbourhood Policy after the Lisbon Treaty and the Arab Spring in 2011, the EU pleaded again to give full attention to democracy considerations. This research paper investigates whether democracy promotion in the ENP towards Morocco has undergone any change since the review of the policy, both in substance and importance. A comparative analysis of European democracy support before and after 2011 in Morocco based on policy reports, financial allocations and conditionality mechanisms reveals that socio- economic conditions are the main focus of EU democracy promotion in Morocco, while most changes can be found in an increased support of civil society. However, the EU seems to repeat its previous behaviour by again prioritising security over democratisation. II LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AP: Action plan CAT: Convention against Torture CEDAW: Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination against Women CFSP: Common Foreign and Security Policy CSF: Civil Society Facility CSO: Civil Society Organisation DCFTA: Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement EEAS: European External Action Service EED: European Endowment for Democracy EIDHR -

36687838.Pdf

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Oregon Scholars' Bank AVOIDING THE ARAB SPRING? THE POLITICS OF LEGITIMACY IN KING MOHAMMED VI’S MOROCCO by MARGARET J. ABNEY A THESIS Presented to the Department of Political Science and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts June 2013 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Margaret J. Abney Title: Avoiding the Arab Spring? The Politics of Legitimacy in King Mohammed VI’s Morocco This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of Political Science by: Craig Parsons Chairperson Karrie Koesel Member Tuong Vu Member and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research and Innovation; Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2013 ii © 2013 Margaret J. Abney iii THESIS ABSTRACT Margaret J. Abney Master of Arts Department of Political Science June 2013 Title: Avoiding the Arab Spring? The Politics of Legitimacy in King Mohammed VI’s Morocco During the 2011 Arab Spring protests, the Presidents of Egypt and Tunisia lost their seats as a result of popular protests. While protests occurred in Morocco during the same time, King Mohammed VI maintained his throne. I argue that the Moroccan king was able to maintain his power because of factors that he has because he is a king. These benefits, including dual religious and political legitimacy, additional control over the military, and a political situation that make King Mohammed the center of the Moroccan political sphere, are not available to the region’s presidents.