Read the Article As

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ordensjournal Ausgabe 21 Anmerkungen Zu Ausgewählten Auszeichnungen März 2011

Ordensjournal Ausgabe 21 Anmerkungen zu ausgewählten Auszeichnungen März 2011 Impressum / © : Uwe Brückner / Am Tegeler Hafen 6 / 13507 Berlin E-Mail: [email protected] URL: http://www.ordensmuseum.de Das von Wilhelm II. im Exil gestiftete Gorgo- Abzeichen und die Gorgo-Becher der Doorner Arbeitsgemeinschaft (D.A.G.) 2. erweiterte Auflage Kaiser Wilhelm II. im Exil. Fotograf: Oscar Tellgmann. Ordensjournal / Ausgabe 21 / März 2011 1 Gorgo-Becher und Gorgo-Abzeichen der Doorner Arbeitsgemeinschaft Diese Ausgabe ist die ergänzte und berichtigte, zweite Auflage des Ordensjournals / Ausgabe 19, und ersetzt diese vollständig! Ordensjournal / Ausgabe 21 / März 2011 2 Während des Aktenstudiums im Geheimen Staatsarchiv Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz, blickte ich zunächst ungläubig auf einige Zeilen, in der Seine Majestät der Kaiser zu bestimmen geruht hatte, wann das Gorgoabzeichen anzulegen wäre. Nun beschäftige ich mich schon seit über 30 Jahren mit deutschen, aber insbesondere auch preußischen Orden, Ehrenzeichen und Abzeichen, aber die Existenz eines Gorgoabzeichens war mir bisher verborgen geblieben. In keiner mir bis dahin bekannten Literatur, die sich mit Themen der Phaleristik beschäftigt, ist dieses Abzeichen je erwähnt worden. Auch die Nachfragen bei anderen, fachkundigen Personen auf dem Gebiet der Orden & Ehrenzeichen brachten keinerlei Erkenntnisse. Da die oben genannte Bestimmung jedoch authentisch war, musste das Abzeichen existiert haben. Deshalb war ich mir sicher, dass es möglich sein musste, mehr über das Abzeichen in Erfahrung zu bringen. Ausgehend von der Bestimmung, wann das Abzeichen angelegt werden sollte, konnten weitere Dokumente gefunden werden, in der auch die Verleihung des Abzeichens dokumentiert wurde. Durch weitere Recherchen von Namen, die ich in den Akten finden konnte, stieß ich auf das Frobenius Institut 1 in Frankfurt am Main. -

The Greatness and Decline of Rome

THE GREATNESS AND DECLINE OF ROME VOL. V. THE REPUBLIC OF AUGUSTUS BY GUGLIELMO FERRERO TRANSLATED BY REV. H. J. CHAYTOR, M.A. HEADMASTER OF PLYMOUTH COLLEGE LONDON WILLIAM HEINEMANN 1909 O 1 All rights reserved P 4 I V.5' ,/ CONTENTS CHAP. PAGB I. The East i " " II. Armenia Capta, SiGNis Receptis . , 28 III. The Great Social Laws of the Year 18 b.c. 45 IV. The " LuDi S^culares " 76 V. The Egypt of the West ...... 104 VI. The Great Crisis in the European Provinces . 121 VII. The Conquest of Germania .... 142 VIII. " H^c EST Italia Diis Sacra" 166 IX. The Altar of Augustus and of Rome .... 185 X. Julia and Tiberius 213 XI. The Exile of Julia 243 XII. The Old Age of Augustus 269 XIII. The Last " Decennium " 291 XIV. Augustus and the Great Empire .... 325 Index 355 — CHAPTER I THE EAST Greece before the Roman conquest—Greece and the Romaa conquest—Greece in the second century of the repubUc—The inability of Rome to remedy the sufferings of Greece—Policy of Augustus in Greece—The theatrical crisis at Rome—The Syrian pantomimes—Pylades of Cilicia—The temple of Rome and Augustus at Pergamum—Asia Minor—The manufac- turing towns in the Greek republics of the coast—The agricultural monarchies of the highlands—The cults of Mithras and Cybele—The unity of Asia Minor—Asiatic Hellenism and Asiatic religions—The Greek republics in the Asiatic monarchy—Asia Minor after a century of Roman rule Weakness, crisis and universal disorder—The critical position of Hellenism and the Jews—Jewish expansion in the east The worship of Rome and Augustus in Asia Minor—The Greek renaissance. -

Up from Egypt: Recent Work on the Date and Pharaoh of the Exodus

Up from Egypt The Date and Pharaoh of the Exodus ~= """'''''"'~ ~ ~ ~_ ~ "" ~ ""''"~ =~~ ""'",,"'''' <==~_....=~=".,~"" "'~~= _~ 0_ ~ ~ ¥ _ ~~ ~ ~~ ~ ~~ ~~~~ V~= .......~=~""""__=~ ~ 'f,.' 'f,.' j\"'A''''A''A'''A'''},/''i•.''''A' 'A "'f..t"A:" A' A.:''A:'''fl,''''A'}j:<K'''X''A: A; '1i -,--- -~- -~ ----- ---~- ~~- Introduction The question of the date and pharaoh of the Exodus has been much disputed for over a centwy and has been a favorite passion and voluminous pastime of biblical scholars. The story of Moses and the Exodus from Egypt told in the first fifteen chapters of the Book of Exodus is magnificent as literary art and inspiring as a scripture of faith. It is the founding event of a great religion, and has been a symbol of salvation and freedom ever since. But is it history? This question has exercised the best scholarly minds for more than a centwy, but has still to be conclusively answered. Given the state of our evidence greater certitude may forever elude us. For outside of the Bible no clear references have been discovered. The Egyptian sources are silent as the tomb, and Near Eastern documents say nothing. None theless, the more we learn about ancient Egyptian and Near Eastern history the more realis tic and authentic in its general features the story appears. Much of what we know about the second millennium BCE and the New Kingdom pro vides a plausible and ordinary context for the extraordinary and miraculous events of the Exodus. The problem with this plausibility is that it comes from other periods as well, from the Middle Kingdom to the Saite-Persian era, as has been asserted by Donald Redford. -

Ritual Landscapes and Borders Within Rock Art Research Stebergløkken, Berge, Lindgaard and Vangen Stuedal (Eds)

Stebergløkken, Berge, Lindgaard and Vangen Stuedal (eds) and Vangen Lindgaard Berge, Stebergløkken, Art Research within Rock and Borders Ritual Landscapes Ritual Landscapes and Ritual landscapes and borders are recurring themes running through Professor Kalle Sognnes' Borders within long research career. This anthology contains 13 articles written by colleagues from his broad network in appreciation of his many contributions to the field of rock art research. The contributions discuss many different kinds of borders: those between landscapes, cultures, Rock Art Research traditions, settlements, power relations, symbolism, research traditions, theory and methods. We are grateful to the Department of Historical studies, NTNU; the Faculty of Humanities; NTNU, Papers in Honour of The Royal Norwegian Society of Sciences and Letters and The Norwegian Archaeological Society (Norsk arkeologisk selskap) for funding this volume that will add new knowledge to the field and Professor Kalle Sognnes will be of importance to researchers and students of rock art in Scandinavia and abroad. edited by Heidrun Stebergløkken, Ragnhild Berge, Eva Lindgaard and Helle Vangen Stuedal Archaeopress Archaeology www.archaeopress.com Steberglokken cover.indd 1 03/09/2015 17:30:19 Ritual Landscapes and Borders within Rock Art Research Papers in Honour of Professor Kalle Sognnes edited by Heidrun Stebergløkken, Ragnhild Berge, Eva Lindgaard and Helle Vangen Stuedal Archaeopress Archaeology Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Gordon House 276 Banbury Road Oxford OX2 7ED www.archaeopress.com ISBN 9781784911584 ISBN 978 1 78491 159 1 (e-Pdf) © Archaeopress and the individual authors 2015 Cover image: Crossing borders. Leirfall in Stjørdal, central Norway. Photo: Helle Vangen Stuedal All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. -

Comune Di Darfo Boario Terme

REGIONE LOMBARDIA (D.G.R. n° XI/4177 del 30 dicembre 2020) Comune di Darfo Boario Terme – Provincia di Brescia Capofila dell’Ambito Territoriale di Valle Camonica, comprendente i Comuni di: Angolo Terme, Artogne, Berzo Demo, Berzo Inferiore, Bienno, Borno, Braone, Breno, Capo di Ponte, Cedegolo, Cerveno, Ceto, Cevo, Cimbergo, Cividate Camuno, Corteno Golgi, Darfo Boario Terme, Edolo, Esine, Gianico, Incudine, Losine, Lozio, Malegno, Malonno, Monno, Niardo, Ono San Pietro, Ossimo, Paisco Loveno, Paspardo, Pian Camuno, Piancogno, Pisogne, Ponte di Legno, Saviore dell'Adamello, Sellero, Sonico, Temù, Vezza d'Oglio, Vione AVVISO PUBBLICO per l’assegnazione delle unità abitative destinate ai servizi abitativi pubblici disponibili nell’Ambito Territoriale di Valle Camonica - PIANO 2021 Localizzate nei Comuni di: BERZO INFERIORE, BIENNO, BRENO, CAPO DI PONTE, CEDEGOLO, CETO, DARFO BOARIO TERME, EDOLO, ESINE, PIAN CAMUNO, PIANCOGNO, TEMÙ Di proprietà dei Comuni di: BERZO INFERIORE, BRENO, CAPO DI PONTE, EDOLO, PIANCOGNO, TEMÙ, nonché dell’ALER di Brescia-Cremona-Mantova PERIODO APERTURA E CHIUSURA DELL’AVVISO dalle ore 9:00 del 7 maggio 2021 alle ore 16:00 del 30 giugno 2021 1. INDIZIONE DELL’AVVISO PUBBLICO 1.1. Ai sensi della D.G.R. del 30 dicembre 2020 n° XI/4177 è indetto l’avviso pubblico per l’assegnazione delle unità abitative disponibili destinate ai servizi abitativi pubblici. 1.2. Le unità abitative di cui al presente avviso pubblico si distinguono in: a) Numero 28 unità abitative immediatamente assegnabili; b) Numero 0 unità abitative che si rendono assegnabili nel periodo intercorrente tra la data di pubblicazione del presente avviso e la scadenza del termine per la presentazione delle domande di assegnazione; c) Numero 0 unità abitative nello stato di fatto non immediatamente assegnabili per carenze di manutenzione, ai sensi dell’articolo 10 del regolamento regionale n. -

Bresciaeprovincia

I S T I T U Z I O N I S C O L A S T I C H E S T A T A L I - B R E S C I A E P R O V I N C I A - A.S. 2019 2020 COMUNE INDIRIZZO COD. MECCAN. TELEFONO-FAX-EMAIL PLESSI - CODICI INDIRIZZI D.S.G.A. DIRIGENTE SCOL. ISTITUTO COMPRENSIVO 0307356669 Sc. Infanzia Adro Bosio Elida Poli Giampietro 0307356653 Sc. Primaria Adro (Ass. Amm.) 1 ADRO Via Nigoline, 16 Sc. Sec. 1° Adro 25030 Adro BSIC835008 [email protected] ISTITUTO COMPRENSIVO 0364591528 Sc. Infanzia Beata Polimeni Valeria Marafante Simonettta 0364599060 Sc. Primaria Artogne-Piancamuno-Beata-Vissone (3 fascia) 2 ARTOGNE Via C. Golgi, 1 Sc. Sec. 1° Artogne 25040 Artogne BSIC80800X [email protected] ISTITUTO COMPRENSIVO 0309747012 Sc. Infanzia Capriano d/C Caprio Gina Festa Federica 0309748870 Sc. Primaria Azzano M.-Capriano d/C-Fenili B.-Mairano 3 AZZANO MELLA Via Paolo VI, 1 Sc. Sec. 1° Azzano 25020 Azzano Mella BSIC89000R [email protected] ISTITUTO COMPRENSIVO 0306821272 Sc. Infanzia Zona Est-Zona Ovest Speranza Eleonora Scaglia Rita Sc. Primaria Via 26 aprile-Via Bellavere (Ass. Amm.) 4 BAGNOLO MELLA Viale Europa, 15 Sc. Sec. 1° Bagnolo M. 25021 Bagnolo Mella BSIC844003 [email protected] ISTITUTO COMPRENSIVO 036599190 - 0365903868 Sc. Infanzia Idro-Anfo-Treviso B. Vaglia Daria Mattina Aristo Pietro Andus 036599121 Sc. Primaria Bagolino-Ponte Caffaro-Idro-Capovalle-Treviso B. (Ass. Amm.) (Reggente) 5 BAGOLINO Via Lombardi, 18 Sc. Sec. 1° Bagolino-Ponte Caffaro-Idro 25072 Bagolino BSIC806008 [email protected] ISTITUTO COMPRENSIVO 030674036 Sc. -

Turnifunzionari17/06/2021 09:33:56

Assegnazione turni Data: dal 19/06/2021 al 19/06/2021 data fascia oraria funzionario tipologia localita' cliente indirizzo 19/06/2021 M. BERTASIO STEFANO Revisioni esterne (597774) San Zeno Naviglio (BS) GERMANI S.P.A. 1199 - AG VITTORIA VIA MAZZINI 8 - REZZATO, tel.030 2593225 19/06/2021 P BERTASIO STEFANO Revisioni esterne (597775) San Zeno Naviglio (BS) GERMANI S.P.A. 1199 - AG VITTORIA VIA MAZZINI 8 - REZZATO, tel.030 2593225 19/06/2021 M BUONO GLORIA Patenti A/B/AM guide (597939) Gardone Val Trompia (BS) 0113 - AU SCAINI ARV SRL VIA MATTEOTTI, 153 - GARDONE VAL TROMPIA, tel.030 8912679 19/06/2021 M BURSESE SALVATORE Patenti A/B/AM guide (597938) BRESCIA (BS) ABA1 VIA SORBANELLA ABA1 - A.B.A. VIA CASTAGNA 39 - BRESCIA, tel. 19/06/2021 M. CACCAVALE UGO Patenti A/B/AM guide (597937) Desenzano del Garda (BS) 0655 - AU DESENZANESE VIA SCAVI ROMANI, 6 - DESENZANO DEL GARDA, tel.030/91.41.084 19/06/2021 P CACCAVALE UGO Patenti A/B/AM guide (597944) Desenzano del Garda (BS) 0655 - AU DESENZANESE VIA SCAVI ROMANI, 6 - DESENZANO DEL GARDA, tel.030/91.41.084 19/06/2021 M DE ANGELIS LUIGI Patenti A/B/AM guide (597935) Rovato (BS) 0306 - AU ARCADIO VIA MARTIRI DELLA LIBERTA - COCCAGLIO, tel.0307709333 PIAN CAMUNO (BS) FRASSI via delle 1379 - AG CONSULENZA TRASPORTI EFFE B S.N.C. DI BIANCHINI 19/06/2021 M. DI CRISTINA VINCENZO Revisioni esterne (597779) VIA FAEDE 3/A - ESINE, tel. sorti,4 EL PIAN CAMUNO (BS) FRASSI via delle 1379 - AG CONSULENZA TRASPORTI EFFE B S.N.C. -

Borsa Di Studio Per Vivere E Studiare All'estero

Con il sostegno di BORSA DI STUDIO PER VIVERE E STUDIARE ALL’ESTERO Grazie alla collaborazione con EDISON, presente sul territorio con i propri impianti idroelettrici, la Fondazione Intercultura ha istituito una borsa di studio totale per vivere e studiare da 3 mesi a un anno scolastico all’estero, per studenti meritevoli nati tra il 01/01/2003 e il 31/12/2006, residenti nei Comuni di Bagolino, Berzo Demo, Bienno, Borno, Braone, Breno, Capo di Ponte, Cedegolo, Cerveno, Ceto, Cevo, Cividate Camuno, Edolo, Esine, Incudine, Losine, Malegno, Malonno, Monno, Niardo, Ono S. Pietro, Ossimo, Piancogno, Sellero, Sonico, Temù, Vezza D'Oglio, Vione Iscrizioni entro e non oltre l’11 gennaio 2021 Scopri maggiori dettagli su www.intercultura.it/gruppo-edison-impianti Per informazioni è possibile contattare Intercultura al numero 06/48882411 (sede di Roma) oppure scrivere a [email protected] L’organizzazione dell’iniziativa è affidata all’Associazione Intercultura, organizzazione senza scopo di lucro, dal 1955 leader nel campo degli scambi scolastici interculturali, eretta in Ente morale posto sotto la tutela del Ministero degli Affari Esteri e riconosciuta con decreto dal Presidente della Repubblica (DPR n. 578/1985). Attraverso l'opera dei volontari dell'Associazione, presenti in tutto il mondo, Intercultura offre agli studenti e alle famiglie coinvolte un percorso di formazione specifica, assistenza durante tutto il programma all'estero e la certificazione delle competenze acquisite. Con il sostegno di BORSA DI STUDIO PER VIVERE E STUDIARE ALL’ESTERO Requisiti dei partecipanti I giovani studenti meritevoli e a basso reddito che desiderano partecipare a questo concorso, devono essere: ✔nati, in generale, tra il 1° gennaio 2003 e il 31 dicembre 2006 e iscritti in una scuola secondaria di II grado in Italia. -

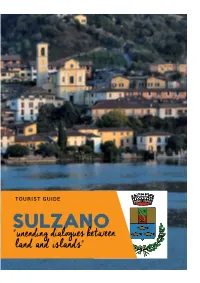

SULZANO " Unending Dialogues Between Land and Islands" SULZANO GUIDE 3

TOURIST GUIDE SULZANO " unending dialogues between land and islands" SULZANO GUIDE 3 SULZANO BACKGROUND HISTORY much quicker and soon small Sulzano derives its name from workshops were turned into actual Sulcius or Saltius. It is located in an factories providing a great deal of area where there was once an ancient employment. Roman settlement and was born as a lake port for the area of Martignago. Along with the economic growth came wealth and during the Twentieth Once, the fishermen’s houses were century the town also became a dotted along the shore and around tourist centre with new hotels and the dock from where the boats would beach resorts. Many were the noble leave to bring the agricultural goods to and middle-class families, from the market at Iseo and the materials Brescia and also from other areas, from the stone quarry of Montecolo, who chose Sulzano as a much-loved used for the production of cement, holiday destination and readily built would transit through here directed elegant lake-front villas. towards the Camonica Valley. At the beginning of the XVI century, the parish was moved to Sulzano and thus the lake town became more important and bigger than the hillside Sulzano is a village that overlooks the one. During the XVII Century, many Brescia side of the Iseo Lake mills were built to make the most of COMUNE DI the driving force of the water that SULZANO flowed abundantly along the valley to the south of the parish. Via Cesare Battisti 91- Sulzano (Bs) Tel. 030/985141 - Fax. -

Statistical Bulletin 20 17 1 - Quarter Quarter 1

quarter 1 - 2017 Statistical Bulletin quarter 1 Statistical Bulletin Statistical publications and distribution options Statistical publications and distribution options The Bank of Italy publishes a quarterly statistical bulletin and a series of reports (most of which are monthly). The statistical information is available on the Bank’s website (www.bancaditalia.it, in the Statistical section) in pdf format and in the BDS on-line. The pdf version of the Bulletin is static in the sense that it contains the information available at the time of publication; by contrast the on-line edition is dynamic in the sense that with each update the published data are revised on the basis of any amendments received in the meantime. On the Internet the information is available in both Italian and English. Further details can be found on the Internet in the Statistics section referred to above. Requests for clarifications concerning data contained in this publication can be sent by e-mail to [email protected]. The source must be cited in any use or dissemination of the information contained in the publications. The Bank of Italy is not responsible for any errors of interpretation of mistaken conclusions drawn on the basis of the information published. Director: GRAZIA MARCHESE For the electronic version: registration with the Court of Rome No. 23, 25 January 2008 ISSN 2281-4671 (on line) Notice to readers Notice to readers I.The appendix contains methodological notes with general information on the statistical data and the sources form which they are drawn. More specific notes regarding individual tables are given at the foot of the tables themselves. -

Pdgunescovcam2007-STORIA.Pdf

BREVE STORIA DELLE RICERCHE PAG. 23-68 1.2 Identità storica Italiano: Piemonte, Lombardia e Canton Ticino, Milano, Touring Club Italiano, p. 595, i due 1.2.1 Breve storia delle ricerche massi di Cemmo (Figg. 3-4). La notizia suscitò Nel 1914 Gualtiero Laeng, riprendendo l’interesse di altri studiosi che giunsero in Val- una nota del 1909 (LAENG G. 1909, Scheda di se- le per occuparsi di queste manifestazioni di ar- gnalazione al Comitato Nazionale per la protezione te preistorica (si veda la Bibliografia: All. 32). del paesaggio e dei monumenti, Touring Club Ita- Negli anni ’20 e ’30 del XX secolo, le ricer- liano), segnalò per la prima volta al grande che si estesero in altre località della Valle Ca- pubblico, sulla Guida d’Italia del Touring Club monica, ad opera di studiosi quali Giovanni Figg. 3-4. Situazione dei Massi di Cemmo all’atto della scoperta negli anni ’30 del XX secolo: sopra il Masso Cemmo 1, sotto il Masso Cemmo 2. 23 Fig. 5. Pianta del Parco Nazionale delle Incisioni Rupestri (Capo di Ponte-Naquane, BS) con le rocce incise rilevate da E. Süss nel 1955. Dopo il silenzio dovuto alla Seconda Guer- ra Mondiale, le ricerche ripresero negli anni ‘50, grazie allo svizzero Hercli Bertogg (diret- tore del Museo di Coira: BERTOGG 1952, 1955, 1956, 1967), ed a studiosi locali quali Gualtie- ro Laeng ed Emanuele Süss (si veda la Biblio- grafia), che lavoravano per il Museo di Scienze Naturali di Brescia. Al Süss si deve la realizzazione della prima carta di distribuzione delle rocce incise della zona di Naquane (SÜSS 1956 a, b), premessa Fig. -

Instrumentalising the Past: the Germanic Myth in National Socialist Context

RJHI 1 (1) 2014 Instrumentalising the Past: The Germanic Myth in National Socialist Context Irina-Maria Manea * Abstract : In the search for an explanatory model for the present or even more, for a fundament for national identity, many old traditions were rediscovered and reutilized according to contemporary desires. In the case of Germany, a forever politically fragmented space, justifying unity was all the more important, especially beginning with the 19 th century when it had a real chance to establish itself as a state. Then, beyond nationalism and romanticism, at the dawn of the Third Reich, the myth of a unified, powerful, pure people with a tradition dating since time immemorial became almost a rule in an ideology that attempted to go back to the past and select those elements which could have ensured a historical basis for the regime. In this study, we will attempt to focus on two important aspects of this type of instrumentalisation. The focus of the discussion is mainly Tacitus’ Germania, a work which has been forever invoked in all sorts of contexts as a means to discover the ancient Germans and create a link to the modern ones, but in the same time the main beliefs in the realm of history and archaeology are underlined, so as to catch a better glimpse of how the regime has been instrumentalising and overinterpreting highly controversial facts. Keywords : Tacitus, Germania, myth, National Socialism, Germany, Kossinna, cultural-historical archaeology, ideology, totalitarianism, falsifying history During the twentieth century, Tacitus’ famous work Germania was massively instrumentalised by the Nazi regime, in order to strengthen nationalism and help Germany gain an aura of eternal glory.