SOME NOTES and REFLECTIONS on the AMERICAN ROAD to MUNICH by Francis L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proceedings 207

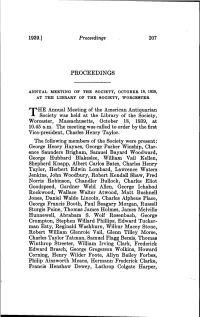

1939.] Proceedings 207 PROCEEDINGS ANNUAL MEETING OP THE SOCIETY, OCTOBER 18, 1939, AT THE LIBEARY OF THE SOCIETY, WORCESTER Annual Meeting of the Anierican Antiquarian -1 Society was held at the Library of the Society, Worcester, Massachusetts, October 18, 1939, at 10.45 a.m. The meeting was called to order by the first Vice-president, Charles Henry Taylor. The following members of the Society were present : George Henry Haynes, George Parker Winship, Clar- ence Saunders Brigham, Samuel Bayard Woodward, George Hubbard Blakeslee, William Vail Kellen, Shepherd Knapp, Albert Carlos Bates, Charles Henry Taylor, Herbert Edwin Lombard, Lawrence Waters Jenkins, John Woodbury, Robert Kendall Shaw, Fred Norris Robinson, Chandler BuUockj Charles Eliot Goodspeed, Gardner Weld Allen, George Ichabod Rockwood, Wallace Walter Atwood, Matt Bushneil Jones, Daniel Waldo Lincoln, Charles Alpheus Place, George Francis Booth, Paul Beagary Morgan, Russell Sturgis Paine, Thomas James Holmes, James Melville Hunnewell, Abraham S. Wolf Rosenbach, George Crompton, Stephen Willard Phillips, Edward Tucker- man Esty, Reginald Washburn, Wilbur Macey Stone, Robert William Glenroie Vail, Glenn Tilley Morse, Charles Taylor Tatman, Samuel Flagg Bemis, Thomas Winthrop Streeter, William Irving Clark, Frederick Edward Brasch, George Gregerson Wolkins, Howard Corning, Henry Wilder Foote, Allyn Bailey Forbes, Philip Ainsworth Means, Hermann Frederick Clarke, Francis Henshaw Dewey, Lathrop Colgate Harper, 208 American Antiquarian Society [Oct., Augustus Peabody Loring, Jr., James Duncan Phillips, Clifford Kenyon Shipton, Alexander Hamilton Bullock, Theron Johnson Damon, Albert White Rice, Fred- erick Lewis Weis, Donald McKay Frost, Harry- Andrew Wright. It was voted to dispense with the reading of the records of the last meeting. The report of the Council of the Society was presented by the Director, Mr. -

University Microfilms Copyright 1984 by Mitchell, Reavis Lee, Jr. All

8404787 Mitchell, Reavis Lee, Jr. BLACKS IN AMERICAN HISTORY TEXTBOOKS: A STUDY OF SELECTED THEMES IN POST-1900 COLLEGE LEVEL SURVEYS Middle Tennessee State University D.A. 1983 University Microfilms Internet ion elæ o N. Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106 Copyright 1984 by Mitchell, Reavis Lee, Jr. All Rights Reserved Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. PLEASE NOTE: In all cases this material has been filmed in the best possible way from the available copy. Problems encountered with this document have been identified here with a check mark V 1. Glossy photographs or pages. 2. Colored illustrations, paper or print_____ 3. Photographs with dark background_____ 4. Illustrations are poor copy______ 5. Pages with black marks, not original copy_ 6. Print shows through as there is text on both sides of page. 7. Indistinct, broken or small print on several pages______ 8. Print exceeds margin requirements______ 9. Tightly bound copy with print lost in spine______ 10. Computer printout pages with indistinct print. 11. Page(s)____________ lacking when material received, and not available from school or author. 12. Page(s) 18 seem to be missing in numbering only as text follows. 13. Two pages numbered _______iq . Text follows. 14. Curling and wrinkled pages______ 15. Other ________ University Microfilms International Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. BLACKS IN AMERICAN HISTORY TEXTBOOKS: A STUDY OF SELECTED THEMES IN POST-190 0 COLLEGE LEVEL SURVEYS Reavis Lee Mitchell, Jr. A dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of Middle Tennessee State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Arts December, 1983 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Whose Brain Drain? Immigrant Scholars and American Views of Germany

Harry & Helen Gray Humanities Program Series Volume 9 WHOSE BRAIN DRAI N? IMMIGRANT SCHOLARS AND AMERICAN VIEWS OF GERMANY Edited by Peter Uwe Hohendahl Cornell University American Institute for Contemporary German Studies The Johns Hopkins University Harry & Helen Gray Humanities Program Series Volume 9 WHOSE BRAIN DRAIN? IMMIGRANT SCHOLARS AND AMERICAN VIEWS OF GERMANY Edited by Peter Uwe Hohendahl Cornell University The American Institute for Contemporary German Studies (AICGS) is a center for advanced research, study and discussion on the politics, culture and society of the Federal Republic of Germany. Established in 1983 and affiliated with The Johns Hopkins University but governed by its own Board of Trustees, AICGS is a privately incorporated institute dedicated to independent, critical and comprehensive analysis and assessment of current German issues. Its goals are to help develop a new generation of American scholars with a thorough understanding of contemporary Germany, deepen American knowledge and understanding of current German developments, contribute to American policy analysis of problems relating to Germany, and promote interdisciplinary and comparative research on Germany. Executive Director: Jackson Janes Board of Trustees, Cochair: Fred H. Langhammer Board of Trustees, Cochair: Dr. Eugene A. Sekulow The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies. ©2001 by the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies ISBN 0-941441-55-5 This Humanities Program Volume is made possible by the Harry & Helen Gray Humanities Program. Additional copies are available for $5.00 to cover postage and handling from the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies, Suite 420, 1400 16th Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. -

Remembering the Civil War in Wisconsin Wisconsin's Famous

SPRING 2011 Remembering the Civil War in Wisconsin Wisconsin's Famous Man Mound BOOK EXCERPT A Nation within a Nation r-^gdby — CURIOUS TO LEARN MORE ABOUT YOUR COMMUNITY'S HISTORY? hether you are curious about your community's ist, how to preserve or share its history, or ways i meet and learn from others who share your terests, the Wisconsin Historical Society can -ielp. We offer a wide variety of services, resources, and networking opportunities to help you discover the unique place you call home. STA7 SATISFY YOUR CURIOSITY wiscons history. WISCONSIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY V I WISCONSIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY Division Administrator & State Historic Preservation Officer Michael E. Stevens Editorial Director Kathryn L. Borkowski Editor Jane M. de Broux Managing Editor Diane T. Drexler Research and Editorial Assistants Rachel Cordasco, Jesse J. Gant, Joel Heiman, Mike Nemer, John 2 Loyal Democrats Nondorf, John Zimm John Cudahy, Jim Farley, and the Designer Politics and Diplomacy of the Zucker Design New Deal Era, 1933-1941 THE WISCONSIN MAGAZINE OF HISTORY (ISSN 0043-6534), by Thomas Spencer published quarterly, is a benefit of full membership in the Wisconsin Historical Society. 16 A Spirit Striding Upon the Earth Full membership levels start at $45 for individuals and $65 for Wisconsin's Famous Man Mound institutions. To join or for more information, visit our Web site at wisconsinhistory.org/membership or contact the Membership by Amy Rosebrough Office at 888-748-7479 or e-mail [email protected]. The Wisconsin Magazine of History has been published quarterly 24 A Nation within a Nation since 1917 by the Wisconsin Historical Society. -

20 American Antiquarian Society Lications of American Writers. One

20 American Antiquarian Society lications of American writers. One of his earliest catalogues was devoted to these early efforts and this has been followed at intervals by others in the same vein. This was, however, only one facet of his interests and the scholarly catalogues he published covering fiction, poetry, drama, and bibliographical works provide a valuable commentary on the history and the changing fashions of American book buying over four de- cades. The shop established on the premises at S West Forty- sixth Street in New York by Kohn and Papantonio shortly after the end of the war has become a mecca for bibliophiles from all over the United States and from foreign countries. It is not overstating the case to say that Kohn became the leading authority on first and important editions of American literature. He was an interested and active member of the American Antiquarian Society. The Society's incomparable holdings in American literature have been enriched by his counsel and his gifts. He will be sorely missed as a member, a friend, and a benefactor. C. Waller Barrett SAMUEL ELIOT MORISON Samuel Eliot Morison was born in Boston on July 9, 1887, and died there nearly eighty-nine years later on May 15, 1976. He lived most of his life at 44 Brimmer Street in Bos- ton. He graduated from Harvard in 1908, sharing a family tradition with, among others, several Samuel Eliots, Presi- dent Charles W. Eliot, Charles Eliot Norton, and Eking E. Morison. During his junior year he decided on teaching and writing history as an objective after graduation and in his twenty-fifth Harvard class report, he wrote: 'History is a hu- mane discipline that sharpens the intellect and broadens the mind, offers contacts with people, nations, and civilizations. -

Suicide Facts Oladeinde Is a Staff Writerall for Hands Suicide Is on the Rise Nationwide

A L p AN Stephen Murphy (left),of Boston, AMSAN Kevin Sitterson (center), of Roper, N.C., and AN Rick Martell,of Bronx, N.Y., await the launch of an F-14 Tomcat on the flight deckof USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN 71). e 4 24 e 6 e e Hidden secrets Operation Deliberate Force e e The holidays are a time for giving. USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN 71) e e proves what it is made of during one of e e Make time for your shipmates- it e e could be the gift of life. the biggest military operations in Europe e e since World War 11. e e e e 6 e e 28 e e Grab those Gifts e e Merchants say thanks to those in This duty’s notso tough e e uniform. Your ID card is worth more Nine-section duty is off to a great start e e e e than you may think. and gets rave reviews aboardUSS e e Anchorage (LSD 36). e e PAGE 17 e e 10 e e The right combination 30 e e e e Norfolk hospital corpsman does studio Sailors care,do their fair share e e time at night. Seabees from CBU420 build a Habitat e e e e for Humanity house in Jacksonville, Fla. e e 12 e e e e Rhyme tyme 36 e e Nautical rhymes bring the past to Smart ideas start here e e e e everyday life. See how many you Sailors learn the ropes and get off to a e e remember. -

Gold Democrats and the Decline of Classical Liberalism, 1896–1900

SUBSCRIBE NOW AND RECEIVE CRISIS AND LEVIATHAN* FREE! “The Independent Review does not accept “The Independent Review is pronouncements of government officials nor the excellent.” conventional wisdom at face value.” —GARY BECKER, Noble Laureate —JOHN R. MACARTHUR, Publisher, Harper’s in Economic Sciences Subscribe to The Independent Review and receive a free book of your choice* such as the 25th Anniversary Edition of Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American Government, by Founding Editor Robert Higgs. This quarterly journal, guided by co-editors Christopher J. Coyne, and Michael C. Munger, and Robert M. Whaples offers leading-edge insights on today’s most critical issues in economics, healthcare, education, law, history, political science, philosophy, and sociology. Thought-provoking and educational, The Independent Review is blazing the way toward informed debate! Student? Educator? Journalist? Business or civic leader? Engaged citizen? This journal is for YOU! *Order today for more FREE book options Perfect for students or anyone on the go! The Independent Review is available on mobile devices or tablets: iOS devices, Amazon Kindle Fire, or Android through Magzter. INDEPENDENT INSTITUTE, 100 SWAN WAY, OAKLAND, CA 94621 • 800-927-8733 • [email protected] PROMO CODE IRA1703 Gold Democrats and the Decline of Classical Liberalism, 1896–1900 —————— ✦ —————— DAVID T. BEITO AND LINDA ROYSTER BEITO n 1896 a new political party was born, the National Democratic Party (NDP). The founders of the NDP included some of the leading exponents of classical I liberalism during the late nineteenth century. Few of those men, however, fore- saw the ultimate fate of their new party and of the philosophy of limited government that it championed. -

Jefferson's Failed Anti-Slavery Priviso of 1784 and the Nascence of Free Soil Constitutionalism

MERKEL_FINAL 4/3/2008 9:41:47 AM Jefferson’s Failed Anti-Slavery Proviso of 1784 and the Nascence of Free Soil Constitutionalism William G. Merkel∗ ABSTRACT Despite his severe racism and inextricable personal commit- ments to slavery, Thomas Jefferson made profoundly significant con- tributions to the rise of anti-slavery constitutionalism. This Article examines the narrowly defeated anti-slavery plank in the Territorial Governance Act drafted by Jefferson and ratified by Congress in 1784. The provision would have prohibited slavery in all new states carved out of the western territories ceded to the national government estab- lished under the Articles of Confederation. The Act set out the prin- ciple that new states would be admitted to the Union on equal terms with existing members, and provided the blueprint for the Republi- can Guarantee Clause and prohibitions against titles of nobility in the United States Constitution of 1788. The defeated anti-slavery plank inspired the anti-slavery proviso successfully passed into law with the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. Unlike that Ordinance’s famous anti- slavery clause, Jefferson’s defeated provision would have applied south as well as north of the Ohio River. ∗ Associate Professor of Law, Washburn University; D. Phil., University of Ox- ford, (History); J.D., Columbia University. Thanks to Sarah Barringer Gordon, Thomas Grey, and Larry Kramer for insightful comment and critique at the Yale/Stanford Junior Faculty Forum in June 2006. The paper benefited greatly from probing questions by members of the University of Kansas and Washburn Law facul- ties at faculty lunches. Colin Bonwick, Richard Carwardine, Michael Dorf, Daniel W. -

Stunde Null: the End and the Beginning Fifty Years Ago." Their Contributions Are Presented in This Booklet

STUNDE NULL: The End and the Beginning Fifty Years Ago Occasional Paper No. 20 Edited by Geoffrey J. Giles GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE WASHINGTON, D.C. STUNDE NULL The End and the Beginning Fifty Years Ago Edited by Geoffrey J. Giles Occasional Paper No. 20 Series editors: Detlef Junker Petra Marquardt-Bigman Janine S. Micunek © 1997. All rights reserved. GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE 1607 New Hampshire Ave., NW Washington, DC 20009 Tel. (202) 387–3355 Contents Introduction 5 Geoffrey J. Giles 1945 and the Continuities of German History: 9 Reflections on Memory, Historiography, and Politics Konrad H. Jarausch Stunde Null in German Politics? 25 Confessional Culture, Realpolitik, and the Organization of Christian Democracy Maria D. Mitchell American Sociology and German 39 Re-education after World War II Uta Gerhardt German Literature, Year Zero: 59 Writers and Politics, 1945–1953 Stephen Brockmann Stunde Null der Frauen? 75 Renegotiating Women‘s Place in Postwar Germany Maria Höhn The New City: German Urban 89 Planning and the Zero Hour Jeffry M. Diefendorf Stunde Null at the Ground Level: 105 1945 as a Social and Political Ausgangspunkt in Three Cities in the U.S. Zone of Occupation Rebecca Boehling Introduction Half a century after the collapse of National Socialism, many historians are now taking stock of the difficult transition that faced Germans in 1945. The Friends of the German Historical Institute in Washington chose that momentous year as the focus of their 1995 annual symposium, assembling a number of scholars to discuss the topic "Stunde Null: The End and the Beginning Fifty Years Ago." Their contributions are presented in this booklet. -

How the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Began, 1914 Reissued 1954

How the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Began By MARY WHITE OVINGTON NATIONAL AssociATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT oF CoLORED PEOPLE 20 WEST 40th STREET, NEW YORK 18, N. Y. MARY DUNLOP MACLEAN MEMORIAL FUND First Printing 1914 HOW THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE BEGAN By MARY WHITE OVINGTON (As Originally printed in 1914) HE National Association for the studying the status of the Negro in T Advancement of Colored People New York. I had investigated his hous is five years old-old enough, it is be ing conditions, his health, his oppor lieved, to have a history; and I, who tunities for work. I had spent many am perhaps its first member, have months in the South, and at the time been chosen as the person to recite it. of Mr. Walling's article, I was living As its work since 1910 has been set in a New York Negro tenement on a forth in its annual reports, I shall Negro street. And my investigations and make it my task to show how it came my surroundings led me to believe with into existence and to tell of its first the writer of the article that "the spirit months of work. of the abolitionists must be revived." In the summer of 1908, the country So I wrote to Mr. Walling, and after was shocked by the account of the race some time, for he was in the West, we riots at Springfield, Illinois. Here, in met in New York in-the first week of the home of Abraham Lincoln, a mob the year 1909. -

How Did Belle La Follette Resist Racial Segregation in Washington D.C., 1913-1914?

Santa Clara University Scholar Commons History College of Arts & Sciences 6-2004 How did Belle La Follette Resist Racial Segregation in Washington D.C., 1913-1914? Nancy Unger Santa Clara University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/history Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Political History Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, Social History Commons, Social Justice Commons, United States History Commons, and the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Unger, N. (2004) How did Belle La Follette Resist Racial Segregation in Washington D.C., 1913-1914? In K. Sklar and T. Dublin (Eds.) Women and Social Movements in the United States, 1775-2000, 8, no. 2. New York: Alexander Street Press. Copyright © 2004 Thomas Dublin, Kathryn Kish Sklar and Alexander Street Press, LLC. Reprinted with permission. Any future reproduction requires permission from original copyright holders. http://asp6new.alexanderstreet.com/tinyurl/tinyurl.resolver.aspx?tinyurl=3CPQ This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. How Did Belle La Follette Oppose Racial Segregation in Washington, D.C., 1913-1914? Abstract Beginning in 1913, progressive reformer Belle Case La Follette wrote a series of articles for the "women's page" of her family's magazine, denouncing the sudden racial segregation in several departments of the federal government. Those articles reveal progressive efforts to appeal specifically to women to combat injustice, and also demonstrate the ability of women to voice important political opinions prior to suffrage. -

Volume 34, Number 2, 2012

Kansas Preservation Volume 34, Number 2 • 2012 REAL PLACES. REAL STORIES. Historical Society Legislative Wrap-Up Historic preservation supporters spent much of the 2012 Kansas legislative Newsletter of the Cultural session advocating for the state historic preservation tax credit program amidst Resources Division Kansas Historical Society a vigorous debate over Kansas tax policy. On May 22 Governor Sam Brownback signed a comprehensive tax-cut bill that lowers personal income tax rates and eliminates state income taxes on the profits of limited liability companies, Volume 34 Number 2 subchapter S corporations, and sole proprietorships. Although the plan Contents eliminates many tax incentives, the historic tax credit program remains intact. 1 Regarding the Partnership Historic Sites donation tax credit program, there Kansas Preservation Alliance Awards was legislative support for continuing the program; however, it was not included 10 in the final bill. The program sunset in accordance with the existing statute on National Register Nominations June 30, 2012. 15 State Rehabilitation Tax Credit Read more: 18 Save the Date – Preservation Symposium kansas.com/2012/05/22/2344393/governor-signs-bill-for-massive. 19 html#storylink=cpy Project Archaeology Unit Find a copy of the bill: kslegislature.org/li/b2011_12/measures/documents/ hb2117_enrolled.pdf KANSAS PRESERVATION Correction Several sharp-eyed readers noticed the population figures listed in “A Tale of Two Published quarterly by the Kansas Historical Cities” article in the volume 34, number 1 2012 issue, mistakenly switched the Society, 6425 SW 6th Avenue, Topeka KS 66615-1099. figures for the African American population with those for all of Wichita. The Please send change of address information corrected figures for African Americans in Wichita are: page 14, 1880: 172 African to the above address or email Americans; 1890: 1,222; 1900: 1,289; 1950: 8,082.