University Microfilms Copyright 1984 by Mitchell, Reavis Lee, Jr. All

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proceedings 207

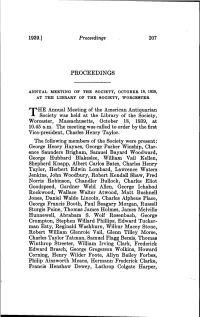

1939.] Proceedings 207 PROCEEDINGS ANNUAL MEETING OP THE SOCIETY, OCTOBER 18, 1939, AT THE LIBEARY OF THE SOCIETY, WORCESTER Annual Meeting of the Anierican Antiquarian -1 Society was held at the Library of the Society, Worcester, Massachusetts, October 18, 1939, at 10.45 a.m. The meeting was called to order by the first Vice-president, Charles Henry Taylor. The following members of the Society were present : George Henry Haynes, George Parker Winship, Clar- ence Saunders Brigham, Samuel Bayard Woodward, George Hubbard Blakeslee, William Vail Kellen, Shepherd Knapp, Albert Carlos Bates, Charles Henry Taylor, Herbert Edwin Lombard, Lawrence Waters Jenkins, John Woodbury, Robert Kendall Shaw, Fred Norris Robinson, Chandler BuUockj Charles Eliot Goodspeed, Gardner Weld Allen, George Ichabod Rockwood, Wallace Walter Atwood, Matt Bushneil Jones, Daniel Waldo Lincoln, Charles Alpheus Place, George Francis Booth, Paul Beagary Morgan, Russell Sturgis Paine, Thomas James Holmes, James Melville Hunnewell, Abraham S. Wolf Rosenbach, George Crompton, Stephen Willard Phillips, Edward Tucker- man Esty, Reginald Washburn, Wilbur Macey Stone, Robert William Glenroie Vail, Glenn Tilley Morse, Charles Taylor Tatman, Samuel Flagg Bemis, Thomas Winthrop Streeter, William Irving Clark, Frederick Edward Brasch, George Gregerson Wolkins, Howard Corning, Henry Wilder Foote, Allyn Bailey Forbes, Philip Ainsworth Means, Hermann Frederick Clarke, Francis Henshaw Dewey, Lathrop Colgate Harper, 208 American Antiquarian Society [Oct., Augustus Peabody Loring, Jr., James Duncan Phillips, Clifford Kenyon Shipton, Alexander Hamilton Bullock, Theron Johnson Damon, Albert White Rice, Fred- erick Lewis Weis, Donald McKay Frost, Harry- Andrew Wright. It was voted to dispense with the reading of the records of the last meeting. The report of the Council of the Society was presented by the Director, Mr. -

Senate (Legislative Day of Wednesday, February 28, 1996)

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 104 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 142 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 29, 1996 No. 26 Senate (Legislative day of Wednesday, February 28, 1996) The Senate met at 11 a.m., on the ex- Senator MURKOWSKI for 15 minutes, able to get this opportunity to go piration of the recess, and was called to Senator DORGAN for 20 minutes; fol- where they can get the help they order by the President pro tempore lowing morning business today at 12 need—perhaps after the regular school [Mr. THURMOND]. noon, the Senate will begin 30 minutes hours. Why would we want to lock chil- of debate on the motion to invoke clo- dren in the District of Columbia into PRAYER ture on the D.C. appropriations con- schools that are totally inadequate, The Chaplain, Dr. Lloyd John ference report. but their parents are not allowed to or Ogilvie, offered the following prayer: At 12:30, the Senate will begin a 15- cannot afford to move them around Let us pray: minute rollcall vote on that motion to into other schools or into schools even Father, we are Your children and sis- invoke cloture on the conference re- in adjoining States? ters and brothers in Your family. port. It is also still hoped that during Today we renew our commitment to today’s session the Senate will be able It is a question of choice and oppor- live and work together here in the Sen- to complete action on legislation ex- tunity. -

The Hilltop 11-2-2004 Magazine

Howard University Digital Howard @ Howard University The iH lltop: 2000 - 2010 The iH lltop Digital Archive 11-2-2004 The iH lltop 11-2-2004 Magazine Hilltop Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://dh.howard.edu/hilltop_0010 Recommended Citation Staff, Hilltop, "The iH lltop 11-2-2004 Magazine" (2004). The Hilltop: 2000 - 2010. 199. https://dh.howard.edu/hilltop_0010/199 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the The iH lltop Digital Archive at Digital Howard @ Howard University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The iH lltop: 2000 - 2010 by an authorized administrator of Digital Howard @ Howard University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Hilltop THE BATTLE: IN AN EPIC BA TILE FOR --:J:n~.r l!liiM1 STANDING BY YOUR MAN: ALWAYS AGREE WITH THEIR RUNNING MATES, BUT THEY MUST STAND BEHIND IHEIR~- . PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATE AND SUPPORT THEM IF THEY WILL BECOME VICE PRESIDENT. Bush and Kerry battle II out for the iob • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • t Kerry and Bush t i J:ompared. •' 'I l •I •I • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • FILEPHOTO -1<now who else ~ Is on the ballet. •• ••••••••• The second in Charge: THE VICE PRESIDENT FILE PHOTO • • • • • • • • The money Find out how • • Spent on the The Electoral • • Campaign College Vote • • Works • FILE PHOTO • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 't ... • • • • Do you know • • Who your • • Senior is? • • FILE PHOTO FILE PHOTO • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Three US Supreme Justices to retire soon MAGAZINE DESIGNED BY ARION JAMERSON I ~ • • • • • •I ,• • • I • I • • • I I • • • • • t .... .. .... FILE PHOTOS The Battle to Become President of the United States ofAme rica • BY NAKIA HILL to the Republican and Democratic Bush had four years to do some Conventions and both candidates thing anything to make life bet Millions of United States positions. -

20 American Antiquarian Society Lications of American Writers. One

20 American Antiquarian Society lications of American writers. One of his earliest catalogues was devoted to these early efforts and this has been followed at intervals by others in the same vein. This was, however, only one facet of his interests and the scholarly catalogues he published covering fiction, poetry, drama, and bibliographical works provide a valuable commentary on the history and the changing fashions of American book buying over four de- cades. The shop established on the premises at S West Forty- sixth Street in New York by Kohn and Papantonio shortly after the end of the war has become a mecca for bibliophiles from all over the United States and from foreign countries. It is not overstating the case to say that Kohn became the leading authority on first and important editions of American literature. He was an interested and active member of the American Antiquarian Society. The Society's incomparable holdings in American literature have been enriched by his counsel and his gifts. He will be sorely missed as a member, a friend, and a benefactor. C. Waller Barrett SAMUEL ELIOT MORISON Samuel Eliot Morison was born in Boston on July 9, 1887, and died there nearly eighty-nine years later on May 15, 1976. He lived most of his life at 44 Brimmer Street in Bos- ton. He graduated from Harvard in 1908, sharing a family tradition with, among others, several Samuel Eliots, Presi- dent Charles W. Eliot, Charles Eliot Norton, and Eking E. Morison. During his junior year he decided on teaching and writing history as an objective after graduation and in his twenty-fifth Harvard class report, he wrote: 'History is a hu- mane discipline that sharpens the intellect and broadens the mind, offers contacts with people, nations, and civilizations. -

Suicide Facts Oladeinde Is a Staff Writerall for Hands Suicide Is on the Rise Nationwide

A L p AN Stephen Murphy (left),of Boston, AMSAN Kevin Sitterson (center), of Roper, N.C., and AN Rick Martell,of Bronx, N.Y., await the launch of an F-14 Tomcat on the flight deckof USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN 71). e 4 24 e 6 e e Hidden secrets Operation Deliberate Force e e The holidays are a time for giving. USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN 71) e e proves what it is made of during one of e e Make time for your shipmates- it e e could be the gift of life. the biggest military operations in Europe e e since World War 11. e e e e 6 e e 28 e e Grab those Gifts e e Merchants say thanks to those in This duty’s notso tough e e uniform. Your ID card is worth more Nine-section duty is off to a great start e e e e than you may think. and gets rave reviews aboardUSS e e Anchorage (LSD 36). e e PAGE 17 e e 10 e e The right combination 30 e e e e Norfolk hospital corpsman does studio Sailors care,do their fair share e e time at night. Seabees from CBU420 build a Habitat e e e e for Humanity house in Jacksonville, Fla. e e 12 e e e e Rhyme tyme 36 e e Nautical rhymes bring the past to Smart ideas start here e e e e everyday life. See how many you Sailors learn the ropes and get off to a e e remember. -

MICHAEL PERMAN Brief Resume Education: B.A. Hertford College

MICHAEL PERMAN Brief Resume Education: B.A. Hertford College, Oxford University, 1963. M.A. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 1965. Ph.D. University of Chicago, 1969 (adviser: John Hope Franklin). Academic Positions: 1967-68. Instructor in History, Ohio State University. 1968-70. Lecturer in American Studies, Manchester University, U.K. 1970-74. Assistant Professor of History, University of Illinois at Chicago. 1974-84. Associate Professor of History, UIC. 1984- . Professor of History, UIC. 1990- . Research Professor in the Humanities, UIC. 1997-2000. Chair, Department of History, UIC. 2002-03. John Adams Distinguished Professor of American History, Utrecht University, Netherlands. Publications: A. Books. Reunion Without Compromise: The South and Reconstruction, 1865-1868. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1973 (also in paperback). The Road to Redemption: Southern Politics, 1869-1879. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1984 (also in paperback). Emancipation and Reconstruction. A volume in the American History Series. Arlington Heights, IL: Harlan Davidson Inc, 1987 (paperback only). Second edition, 2003. Struggle for Mastery: Disfranchisement in the South, 1888-1908. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001 (also in paperback). Pursuit of Unity: A Political History of the American South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009 (paperback, 2011). The Southern Political Tradition. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2012 (also in paperback). B. Edited Books. Perspectives on the American Past: Readings and Commentary. Two Volumes. Scott, Foresman/HarperCollins, 1989. Revised 2nd. edition: D.C. Heath/ Houghton Mifflin, 1995. Major Problems in the Civil War and Reconstruction. D.C. Heath, 1991. Revised 2nd. edition, Houghton Mifflin, 1998. -

Jefferson's Failed Anti-Slavery Priviso of 1784 and the Nascence of Free Soil Constitutionalism

MERKEL_FINAL 4/3/2008 9:41:47 AM Jefferson’s Failed Anti-Slavery Proviso of 1784 and the Nascence of Free Soil Constitutionalism William G. Merkel∗ ABSTRACT Despite his severe racism and inextricable personal commit- ments to slavery, Thomas Jefferson made profoundly significant con- tributions to the rise of anti-slavery constitutionalism. This Article examines the narrowly defeated anti-slavery plank in the Territorial Governance Act drafted by Jefferson and ratified by Congress in 1784. The provision would have prohibited slavery in all new states carved out of the western territories ceded to the national government estab- lished under the Articles of Confederation. The Act set out the prin- ciple that new states would be admitted to the Union on equal terms with existing members, and provided the blueprint for the Republi- can Guarantee Clause and prohibitions against titles of nobility in the United States Constitution of 1788. The defeated anti-slavery plank inspired the anti-slavery proviso successfully passed into law with the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. Unlike that Ordinance’s famous anti- slavery clause, Jefferson’s defeated provision would have applied south as well as north of the Ohio River. ∗ Associate Professor of Law, Washburn University; D. Phil., University of Ox- ford, (History); J.D., Columbia University. Thanks to Sarah Barringer Gordon, Thomas Grey, and Larry Kramer for insightful comment and critique at the Yale/Stanford Junior Faculty Forum in June 2006. The paper benefited greatly from probing questions by members of the University of Kansas and Washburn Law facul- ties at faculty lunches. Colin Bonwick, Richard Carwardine, Michael Dorf, Daniel W. -

Above the World: William Jennings Bryan's View of the American

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: Above the World: William Jennings Bryan’s View of the American Nation in International Affairs Full Citation: Arthur Bud Ogle, “Above the World: William Jennings Bryan’s View of the American Nation in International Affairs,” Nebraska History 61 (1980): 153-171. URL of article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/1980-2-Bryan_Intl_Affairs.pdf Date: 2/17/2010 Article Summary: One of the major elements in Bryan’s intellectual and political life has been largely ignored by both critics and admirers of William Jennings Bryan: his vital patriotism and nationalism. By clarifying Bryan’s Americanism, the author illuminates an essential element in his political philosophy and the consistent reason behind his foreign policy. Domestically Bryan thought the United States could be a unified monolithic community. Internationally he thought America still dominated her hemisphere and could, by sheer energy and purity of commitment, re-order the world. Bryan failed to understand that his vision of the American national was unrealizable. The America he believed in was totally vulnerable to domestic intolerance and international arrogance. -

Bernard Bailyn, W

Acad. Quest. (2021) 34.1 10.51845/34s.1.24 DOI 10.51845/34s.1.24 Reviews He won the Pulitzer Prize in history twice: in 1968 for The Ideological Illuminating History: A Retrospective Origins of the American Revolution of Seven Decades, Bernard Bailyn, W. and in 1987 for Voyagers to the West, W. Norton & Company, 2020, 270 pp., one of several volumes he devoted $28.95 hardbound. to the rising field of Atlantic history. Though Bailyn illuminated better than most scholars the contours of Bernard Bailyn: An seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Historian to Learn From American history, his final book hints at his growing concern about the Robert L. Paquette rampant opportunism and pernicious theoretical faddishness that was corrupting the discipline he loved and to which he had committed his Bernard Bailyn died at the age professional life. of ninety-seven, four months after Illuminating History consists of publication of this captivating curio five chapters. Each serves as kind of of a book, part autobiography, part a scenic overlook during episodes meditation, part history, and part of a lengthy intellectual journey. historiography. Once discharged At each stop, Bailyn brings to the from the army at the end of World fore little known documents or an War II and settled into the discipline obscure person’s life to open up of history at Harvard University, views into a larger, more complicated Bailyn undertook an ambitious quest universe, which he had tackled to understand nothing less than with greater depth and detail in the structures, forces, and ideas previously published books and that ushered in the modern world. -

Section IV. for Further Reading

Section IV. For Further Reading 97 Books Abbott, Martin. The Freedmen’s Bureau in South Carolina, 1865-1872. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1967. African American Historic Places in South Carolina . Columbia: South Carolina Department of Archives and History, March 2007. Anderson, Eric and Alfred A. Moss, Jr., eds. The Facts of Reconstruction: Essays in Honor of John Hope Franklin. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1991. Baker, Bruce E. What Reconstruction Meant: Historical Memory in the American South. Charlottesville: University of Virginia, 2007. Bethel, Elizabeth Ruth. Promiseland: A Century of Life in a Negro Community. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1981. Bleser, Carol K. Rothrock. The Promised Land: The History of the South Carolina Land Commission, 1869-1890. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1969. Brown, Thomas J., ed. Reconstructions: New Perspectives on the Postbellum United States . New York: Oxford University Press, 2006. Bryant, Lawrence C. South Carolina Negro Legislators. Orangeburg: South Carolina State College, 1974. Budiansky, Stephen. The Bloody Shirt: Terror after Appomattox. New York: Viking, 2008. Edgar, Walter. South Carolina: A History. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1998. Edgar, Walter, ed. The South Carolina Encyclopedia. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1998. Dray, Philip. Capitol Men: The Epic Story of Reconstruction through the Lives of the First Black Congressmen. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 2008. Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877 . New York: Harper & Row, 1988. Franklin, John Hope. The Color Line: Legacy for the Twenty-First Century. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1993. Franklin, John Hope. Race and History: Selected Essays, 1938-1988. -

The Emancipation Proclamation, an Act of Justice

The Emancipation Proclamation An Act of Justice I I By John Hope Franklin hursday, January 1, 1863, was a bright, crisp day in the nation's capital. The previous day had been a strenu ous one for President Lincoln, but New Year's Day was to be even more strenuous. So he rose early. There was much to do, not the least of which was to put the finishing touches on the Emancipation Proclamation. At 1010:45:45 the document was brought to the White House by Secretary of State William Seward. The President signed it, but he noticed an error in the superscription. It read, "In testimony whereof I have hereunto set my name and caused the seal of the United States to be affixed." The President had never used that form in proclamations, always preferring to say "In testimony whereof I have hereunto set my hand...... ." He asked Seward to make the correction, and the formal signing would be made on the corrected copy. The traditional New Year's Day reception at the White House be gan that morning at eleven o'clock. Members of the cabinet and the diplomatic corps were among the first to arrive.arrive. Officers of the army and navy arrived in a body at half past eleven. The public was ad mitted at noon, and then Seward and his son Frederick, the assistant secretary of state, returned with the corrected draft. The rigid laws of etiquette held the President to his duty for three hours, as his secre taries Nicholay and Hay observed. -

By Leroy T. Hopkins, Jr., Phd President, African American Historical Society of South Central Pennsylvania June 2020

By Leroy T. Hopkins, Jr., PhD President, African American Historical Society of South Central Pennsylvania June 2020 1838: Pennsylvania State Constitution amended. Article III on voting rights read, in part: “ ith this action men of African descent in Pennsylvania were deprived of a right that many had regularly exercised. The response was W immediate. Some members of the Constitution’s Legislative Committee refused to set their signatures to the document on this exclusion, including State Representative Thaddeus Stevens of Gettysburg. Protest meetings were convened to petition the state legislature to remedy this wrong. Men from Lancaster County were involved in a number of those conventions, notably Stephen Smith and William Whipper, the wealthy Black entrepreneurs and clandestine workers on the Underground Railroad from the Susquehanna Riverfront community of Columbia. This publication commemorates some of the people of Lancaster County who endured generations of disenfranchisement, and who planned and participated in public demonstrations during the Spring of 1870 to celebrate the ratification of the 15th Amendment to the United States Constitution. The Amendment states: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” Despite the amendment, by the late 1870s discriminatory practices were used to prevent Black people from exercising their right to vote, especially in the South. It wasn’t until the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that legal barriers were outlawed if they denied African-Americans their right to vote. ©—African American Historical Society of South Central Pennsylvania—June 2020 1 n important protest meeting was the convention held in Harrisburg in 1848.