Curtis Putnam Nettels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proceedings 207

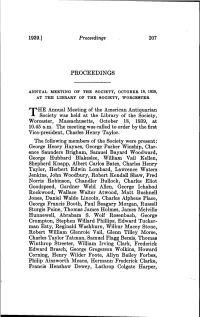

1939.] Proceedings 207 PROCEEDINGS ANNUAL MEETING OP THE SOCIETY, OCTOBER 18, 1939, AT THE LIBEARY OF THE SOCIETY, WORCESTER Annual Meeting of the Anierican Antiquarian -1 Society was held at the Library of the Society, Worcester, Massachusetts, October 18, 1939, at 10.45 a.m. The meeting was called to order by the first Vice-president, Charles Henry Taylor. The following members of the Society were present : George Henry Haynes, George Parker Winship, Clar- ence Saunders Brigham, Samuel Bayard Woodward, George Hubbard Blakeslee, William Vail Kellen, Shepherd Knapp, Albert Carlos Bates, Charles Henry Taylor, Herbert Edwin Lombard, Lawrence Waters Jenkins, John Woodbury, Robert Kendall Shaw, Fred Norris Robinson, Chandler BuUockj Charles Eliot Goodspeed, Gardner Weld Allen, George Ichabod Rockwood, Wallace Walter Atwood, Matt Bushneil Jones, Daniel Waldo Lincoln, Charles Alpheus Place, George Francis Booth, Paul Beagary Morgan, Russell Sturgis Paine, Thomas James Holmes, James Melville Hunnewell, Abraham S. Wolf Rosenbach, George Crompton, Stephen Willard Phillips, Edward Tucker- man Esty, Reginald Washburn, Wilbur Macey Stone, Robert William Glenroie Vail, Glenn Tilley Morse, Charles Taylor Tatman, Samuel Flagg Bemis, Thomas Winthrop Streeter, William Irving Clark, Frederick Edward Brasch, George Gregerson Wolkins, Howard Corning, Henry Wilder Foote, Allyn Bailey Forbes, Philip Ainsworth Means, Hermann Frederick Clarke, Francis Henshaw Dewey, Lathrop Colgate Harper, 208 American Antiquarian Society [Oct., Augustus Peabody Loring, Jr., James Duncan Phillips, Clifford Kenyon Shipton, Alexander Hamilton Bullock, Theron Johnson Damon, Albert White Rice, Fred- erick Lewis Weis, Donald McKay Frost, Harry- Andrew Wright. It was voted to dispense with the reading of the records of the last meeting. The report of the Council of the Society was presented by the Director, Mr. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION ON DECEMBER 7, 1968, Lawrence Henry Gipson celebrated 0his eighty-eighth birthday. An active scholar for the past sixty-five years, Gipson continues to contribute articles and re- views to scholarly journals while completing his life work, The British Einpire before the American Revolution. This historical classic appeared in thirteen volumes published between 1936 and 1967. Two further bibliographical volumes covering printed ma- terials and unpublished manuscripts will appear in 1969 and 1970 bringing to a conclusion a project conceived nearly a half century ago. Certainly these volumes, for which he has received the Loubat Prize, the Bancroft Prize in American History, and the Pulitzer Prize in American History, mark Gipson as one of the master historians of our time. Born in Greeley, Colorado, in 1880, and raised as the son of the local newspaper editor in Caldwell, Idaho; Gipson planned to be a journalist before receiving the opportunity to leave the Uni- versity of Idaho where he had earned an A.B. degree in 1903 and go to Oxford with the first group of Rhodes scholars in 1904. In "Recollections," he relates an early experience at Oxford which determined the future direction of his life. Following the comple- tion of his B.A. degree at Oxford and a brief stint teaching at the College of Idaho, Gipson went to work on the British Empire with Charles McLean Andrews at Yale University from which he received a Ph.D. degree in 1918. Gipson has taught at a number of colleges and universities in- cluding Oxford where he served as Harmsworth Professor in 1951-1952, but most of his years have been spent at Lehigh Uni- versity in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. -

University Microfilms Copyright 1984 by Mitchell, Reavis Lee, Jr. All

8404787 Mitchell, Reavis Lee, Jr. BLACKS IN AMERICAN HISTORY TEXTBOOKS: A STUDY OF SELECTED THEMES IN POST-1900 COLLEGE LEVEL SURVEYS Middle Tennessee State University D.A. 1983 University Microfilms Internet ion elæ o N. Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106 Copyright 1984 by Mitchell, Reavis Lee, Jr. All Rights Reserved Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. PLEASE NOTE: In all cases this material has been filmed in the best possible way from the available copy. Problems encountered with this document have been identified here with a check mark V 1. Glossy photographs or pages. 2. Colored illustrations, paper or print_____ 3. Photographs with dark background_____ 4. Illustrations are poor copy______ 5. Pages with black marks, not original copy_ 6. Print shows through as there is text on both sides of page. 7. Indistinct, broken or small print on several pages______ 8. Print exceeds margin requirements______ 9. Tightly bound copy with print lost in spine______ 10. Computer printout pages with indistinct print. 11. Page(s)____________ lacking when material received, and not available from school or author. 12. Page(s) 18 seem to be missing in numbering only as text follows. 13. Two pages numbered _______iq . Text follows. 14. Curling and wrinkled pages______ 15. Other ________ University Microfilms International Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. BLACKS IN AMERICAN HISTORY TEXTBOOKS: A STUDY OF SELECTED THEMES IN POST-190 0 COLLEGE LEVEL SURVEYS Reavis Lee Mitchell, Jr. A dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of Middle Tennessee State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Arts December, 1983 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

20 American Antiquarian Society Lications of American Writers. One

20 American Antiquarian Society lications of American writers. One of his earliest catalogues was devoted to these early efforts and this has been followed at intervals by others in the same vein. This was, however, only one facet of his interests and the scholarly catalogues he published covering fiction, poetry, drama, and bibliographical works provide a valuable commentary on the history and the changing fashions of American book buying over four de- cades. The shop established on the premises at S West Forty- sixth Street in New York by Kohn and Papantonio shortly after the end of the war has become a mecca for bibliophiles from all over the United States and from foreign countries. It is not overstating the case to say that Kohn became the leading authority on first and important editions of American literature. He was an interested and active member of the American Antiquarian Society. The Society's incomparable holdings in American literature have been enriched by his counsel and his gifts. He will be sorely missed as a member, a friend, and a benefactor. C. Waller Barrett SAMUEL ELIOT MORISON Samuel Eliot Morison was born in Boston on July 9, 1887, and died there nearly eighty-nine years later on May 15, 1976. He lived most of his life at 44 Brimmer Street in Bos- ton. He graduated from Harvard in 1908, sharing a family tradition with, among others, several Samuel Eliots, Presi- dent Charles W. Eliot, Charles Eliot Norton, and Eking E. Morison. During his junior year he decided on teaching and writing history as an objective after graduation and in his twenty-fifth Harvard class report, he wrote: 'History is a hu- mane discipline that sharpens the intellect and broadens the mind, offers contacts with people, nations, and civilizations. -

Suicide Facts Oladeinde Is a Staff Writerall for Hands Suicide Is on the Rise Nationwide

A L p AN Stephen Murphy (left),of Boston, AMSAN Kevin Sitterson (center), of Roper, N.C., and AN Rick Martell,of Bronx, N.Y., await the launch of an F-14 Tomcat on the flight deckof USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN 71). e 4 24 e 6 e e Hidden secrets Operation Deliberate Force e e The holidays are a time for giving. USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN 71) e e proves what it is made of during one of e e Make time for your shipmates- it e e could be the gift of life. the biggest military operations in Europe e e since World War 11. e e e e 6 e e 28 e e Grab those Gifts e e Merchants say thanks to those in This duty’s notso tough e e uniform. Your ID card is worth more Nine-section duty is off to a great start e e e e than you may think. and gets rave reviews aboardUSS e e Anchorage (LSD 36). e e PAGE 17 e e 10 e e The right combination 30 e e e e Norfolk hospital corpsman does studio Sailors care,do their fair share e e time at night. Seabees from CBU420 build a Habitat e e e e for Humanity house in Jacksonville, Fla. e e 12 e e e e Rhyme tyme 36 e e Nautical rhymes bring the past to Smart ideas start here e e e e everyday life. See how many you Sailors learn the ropes and get off to a e e remember. -

Jefferson's Failed Anti-Slavery Priviso of 1784 and the Nascence of Free Soil Constitutionalism

MERKEL_FINAL 4/3/2008 9:41:47 AM Jefferson’s Failed Anti-Slavery Proviso of 1784 and the Nascence of Free Soil Constitutionalism William G. Merkel∗ ABSTRACT Despite his severe racism and inextricable personal commit- ments to slavery, Thomas Jefferson made profoundly significant con- tributions to the rise of anti-slavery constitutionalism. This Article examines the narrowly defeated anti-slavery plank in the Territorial Governance Act drafted by Jefferson and ratified by Congress in 1784. The provision would have prohibited slavery in all new states carved out of the western territories ceded to the national government estab- lished under the Articles of Confederation. The Act set out the prin- ciple that new states would be admitted to the Union on equal terms with existing members, and provided the blueprint for the Republi- can Guarantee Clause and prohibitions against titles of nobility in the United States Constitution of 1788. The defeated anti-slavery plank inspired the anti-slavery proviso successfully passed into law with the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. Unlike that Ordinance’s famous anti- slavery clause, Jefferson’s defeated provision would have applied south as well as north of the Ohio River. ∗ Associate Professor of Law, Washburn University; D. Phil., University of Ox- ford, (History); J.D., Columbia University. Thanks to Sarah Barringer Gordon, Thomas Grey, and Larry Kramer for insightful comment and critique at the Yale/Stanford Junior Faculty Forum in June 2006. The paper benefited greatly from probing questions by members of the University of Kansas and Washburn Law facul- ties at faculty lunches. Colin Bonwick, Richard Carwardine, Michael Dorf, Daniel W. -

Above the World: William Jennings Bryan's View of the American

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: Above the World: William Jennings Bryan’s View of the American Nation in International Affairs Full Citation: Arthur Bud Ogle, “Above the World: William Jennings Bryan’s View of the American Nation in International Affairs,” Nebraska History 61 (1980): 153-171. URL of article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/1980-2-Bryan_Intl_Affairs.pdf Date: 2/17/2010 Article Summary: One of the major elements in Bryan’s intellectual and political life has been largely ignored by both critics and admirers of William Jennings Bryan: his vital patriotism and nationalism. By clarifying Bryan’s Americanism, the author illuminates an essential element in his political philosophy and the consistent reason behind his foreign policy. Domestically Bryan thought the United States could be a unified monolithic community. Internationally he thought America still dominated her hemisphere and could, by sheer energy and purity of commitment, re-order the world. Bryan failed to understand that his vision of the American national was unrealizable. The America he believed in was totally vulnerable to domestic intolerance and international arrogance. -

The Metahistory of the American West

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2001 The metahistory of the American West Don Franklin Shepherd University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Shepherd, Don Franklin, "The metahistory of the American West" (2001). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 2476. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/2ir7-csaz This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while otfiers may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and tfiere are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Bernard Bailyn, W

Acad. Quest. (2021) 34.1 10.51845/34s.1.24 DOI 10.51845/34s.1.24 Reviews He won the Pulitzer Prize in history twice: in 1968 for The Ideological Illuminating History: A Retrospective Origins of the American Revolution of Seven Decades, Bernard Bailyn, W. and in 1987 for Voyagers to the West, W. Norton & Company, 2020, 270 pp., one of several volumes he devoted $28.95 hardbound. to the rising field of Atlantic history. Though Bailyn illuminated better than most scholars the contours of Bernard Bailyn: An seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Historian to Learn From American history, his final book hints at his growing concern about the Robert L. Paquette rampant opportunism and pernicious theoretical faddishness that was corrupting the discipline he loved and to which he had committed his Bernard Bailyn died at the age professional life. of ninety-seven, four months after Illuminating History consists of publication of this captivating curio five chapters. Each serves as kind of of a book, part autobiography, part a scenic overlook during episodes meditation, part history, and part of a lengthy intellectual journey. historiography. Once discharged At each stop, Bailyn brings to the from the army at the end of World fore little known documents or an War II and settled into the discipline obscure person’s life to open up of history at Harvard University, views into a larger, more complicated Bailyn undertook an ambitious quest universe, which he had tackled to understand nothing less than with greater depth and detail in the structures, forces, and ideas previously published books and that ushered in the modern world. -

Transnationalism and American Studies in Place

The Japanese Journal of American Studies, No. 18 (2007) Transnationalism and American Studies in Place Karen HALTTUNEN* When George Lipsitz proclaimed, in 2001, that the field of American studies was “in a moment of danger,” he demonstrated once again the cultural power of the jeremiad that has shaped this academic enterprise since its emergence in the first half of the twentieth century.1 To a sig- nificant degree, the intellectual vigor of American studies arises from its never-ending habit of self-reflection and critique. Since the 1960s, three successive and inter-related crises have challenged American studies practitioners to rethink our most fundamental assumptions about our area of scholarship. The first directly challenged the consensus-oriented myth-and-symbol school that achieved its apex in the 1950s, by turning attention from a homogeneous “American mind” to a rich proliferation of “minority” histories, literatures, and cultures, exploring the seemingly infinite variety of identities shaped by social class, race and ethnicity, gender and sexuality, and, most recently, physical ability. The second responded to Benedict Anderson’s concept of the nation as “imagined community” by exploring the fictive qualities of American bourgeois nationalism, with special attention to American exceptionalism, and to the ways in which “American national identity has been produced pre- cisely in opposition to, and therefore in relationship with, that which it Copyright © 2007 Karen Halttunen. All rights reserved. This work may be used, with this notice included, for noncommercial purposes. No copies of this work may be distributed, electronically or otherwise, in whole or in part, without permission from the author. -

American Exceptionalism Or Atlantic Unity? Fredrick Jackson Turner and the Enduring Problem of American Historiography

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 89 Number 3 Article 4 7-1-2014 American Exceptionalism or Atlantic Unity? Fredrick Jackson Turner and the Enduring Problem of American Historiography Kevin Jon Fernlund Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Fernlund, Kevin Jon. "American Exceptionalism or Atlantic Unity? Fredrick Jackson Turner and the Enduring Problem of American Historiography." New Mexico Historical Review 89, 3 (2014). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol89/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. American Exceptionalism or Atlantic Unity? Frederick Jackson Turner and the Enduring Problem of American Historiography • KEVIN JON FERNLUND The Problem: Europe and the History of America n 1892 the United States celebrated the four hundredth anniversary of Chris- topher Columbus’s discovery of lands west of Europe, on the far side of the IAtlantic Ocean. To mark this historic occasion, and to showcase the nation’s tremendous industrial progress, the city of Chicago hosted the World’s Colum- bian Exposition. Chicago won the honor after competing with other major U.S. cities, including New York. Owing to delays, the opening of the exposition was pushed back to 1893. This grand event was ideally timed to provide the coun- try’s nascent historical profession with the opportunity to demonstrate its value to the world. The American Historical Association (AHA) was founded only a few years prior in 1884, and incorporated by the U.S. -

1987 Spring – Bogue – “The History of the American Political Party System”

UN I VERS I TY OF WI SCONSIN Department of History (Sem. II - 1986-87) History 901 (The History of the American Political Party System) Mr. Bogue I APPROACHES TO THE STUDY OF AMERICAN POLITICAL PARTIES Robert R. Alford, "Class Voting in the Anglo-American Political Systems," in Seymour M. Lipsett and Stein Rokkan, PARTY SYSTEMS AND VOTER ALIGNMENTS: AN APPROACH TO COMPARATIVE POLITICS, 67-93. Gabriel W. Almond, et al., CRISIS, CHOICE AND CHANGE: HISTORICAL STUDIES OF POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT. *Richard F. Bensel, SECTIONALISM AND AMERICAN POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT, 1880-1980. Lee Benson, et al., "Toward a Theory of Stability and Change in American Voting Patterns, New York State, 1792-1970," in Joel Silbey, et al, THE HISTORY OF AMERICAN ELECTORAL BEHAVIOR, 78-105. Lee Benson, "Research Problems in American Political Historiography," in Mirra Komarovsky, COMMON FRONTIERS OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES, 113-83. Bernard L. Berelson, et al., VOTING: A STUDY OF OPINION FORMATION IN A PRESIDENTIAL CAMPAIGN. Allan G. Bogue et al., "Members of the House of Representatives and the Processes of Modernization, 1789-1960," JOURNAL OF AMERICAN HISTORY, LXIII, (September 1976), 275-302. Cyril E. Black, THE DYNAMICS OF MODERNIZATION Paul F. Bourke and Donald A. DeBats, "Individuals and Aggregates: A Note on Historical Data and Assumptions," SOCIAL SCIENCE HISTORY (Spring 1980), 229-50. Paul F. Bourke and Donald A. DeBats, "Identifiable Voting in Nineteenth Century America, Toward a Comparison of Britain and the United States Before the Secret Ballot," PERSPECTIVES IN AMERICAN HISTORY, XI(l977-78), 259-288. David Brady, "A Reevaluation of Realignments in American Politics," American Political Science Review 79(March 1985), 28-49.