Gold Democrats and the Decline of Classical Liberalism, 1896–1900

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 5.1: Land Use, Zoning, and Public Policy A. INTRODUCTION

Chapter 5.1: Land Use, Zoning, and Public Policy A. INTRODUCTION This chapter describes existing land use, zoning, and public policies applicable to the proposed project and evaluates potential significant adverse effects that may result from implementation of the proposed flood protection system. Potential significant adverse effects to land use as a result of implementing the flood protection system are also evaluated. Potential land use issues include known or likely changes in current land uses within the study area, as well as the proposed project’s potential effect on existing and future land use patterns. Potential zoning and public policy issues include the compatibility of the proposed project with existing zoning and consistency with existing applicable public policies. PROJECT AREA ONE Project Area One extends from Montgomery Street on the south to the north end of John V. Lindsay East River Park (East River Park) at about East 13th Street. Project Area One consists primarily of the Franklin Delano Roosevelt East River Drive (FDR Drive) right-of-way, a portion of Pier 42 and Corlears Hook Park as well as East River Park. The majority of Project Area One is within East River Park and includes four existing pedestrian bridges across the FDR Drive to East River Park (Corlears Hook, Delancey Street, East 6th Street, and East 10th Street Bridges) and the East Houston Street overpass. Project Area One is located within Manhattan Community District 3, and borders portions of the Lower East Side and East Village neighborhoods. PROJECT AREA TWO Project Area Two extends north and east from Project Area One, from East 13th Street to East 25th Street. -

Garland's Million: the Radical Experiment To

October 14, 2019 To: ABF Legal History Seminar From: John Fabian Witt Re: October 23 seminar Thanks so much for looking at my drafts and coming to my session! I’m thrilled to have been invited to Chicago. I am attaching chapters 5 and 8 from my book-in-progress, tentatively titled Garland’s Million: The Radical Experiment to Save American Democracy. The book is the story of an organization known informally as the Garland Fund or formally as the American Fund for Public Service: a philanthropic foundation established in 1922 to give money to liberal and left causes. The Fund figures prominently in the history of civil rights lawyering because of its role setting in motion the early stages of the NAACP’s litigation campaign that led a quarter-century later to Brown v. Board of Education. I hope you will be able to get some sense of the project from the crucial chapters I’ve attached here. These chapters come from Part 2 of the book. Part 1 focuses on Roger Baldwin, the founder of the ACLU and the principal energy behind the Fund. Part 2 (including the chapters here) focuses on James Weldon Johnson, who ran the NAACP during the 1920s and was a board member of the Fund. Parts 3 and 4 turn respectively to Elizabeth Gurley Flynn (a labor radical on the board) and Felix Frankfurter, who in the 1920s served as a key outside consultant and counsel to the Fund. To set the stage, readers have learned in Part 1 about Baldwin as a disillusioned reformer, who advocated progressive programs like the initiative and referendum only to see direct democracy produce a wave of white supremacist initiatives. -

Bryan's “Cross of Gold” Speech: Mesmerizing the Masses

Bryan’s “Cross of Gold” Speech: Mesmerizing the Masses The most famous speech in American political history was delivered by William Jennings Bryan on July 9, 1896, at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. The issue was whether to endorse the free coinage of silver at a ratio of silver to gold of 16 to 1. (This inflationary measure would have increased the amount of money in circulation and aided cash-poor and debt-burdened farmers.) After speeches on the subject by several U.S. Senators, Bryan rose to speak. The thirty-six-year-old former Congressman from Nebraska aspired to be the Democratic nominee for president, and he had been skillfully, but quietly, building support for himself among the delegates. His dramatic speaking style and rhetoric roused the crowd to frenzy. The response, wrote one reporter, “came like one great burst of artillery.” Men and women screamed and waved their hats and canes. “Some,” wrote another reporter, “like demented things, divested themselves of their coats and flung them high in the air.” The next day the convention nominated Bryan for President on the fifth ballot. The full text of William Jenning Bryan’s famous “Cross of Gold” speech appears below. The audio portion is an excerpt. [Note on the recording: In 1896 recording technology was in its infancy, and recording a political convention would have been impossible. But in the early 20th century, the fame of Bryan’s “Cross of Gold” speech led him to repeat it numerous times on the Chautauqua lecture circuit where he was an enormously popular speaker. -

Free Silver"; Montana's Political Dream of Economic Prosperity, 1864-1900

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1969 "Free silver"; Montana's political dream of economic prosperity, 1864-1900 James Daniel Harrington The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Harrington, James Daniel, ""Free silver"; Montana's political dream of economic prosperity, 1864-1900" (1969). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 1418. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1418 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "FREE SILVER MONTANA'S POLITICAL DREAM OF ECONOMIC PROSPERITY: 1864-19 00 By James D. Harrington B. A. Carroll College, 1961 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1969 Approved by: Chairman, Board of Examiners . /d . Date UMI Number: EP36155 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Disaartation Publishing UMI EP36155 Published by ProQuest LLC (2012). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. -

The Case for a 100 Percent Gold Dollar by Murray N

The Case for a 100 Percent Gold Dollar By Murray N. Rothbard Publication history: Leland Yeager (ed.), In Search of a Monetary Constitution. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1962, pp. 94-136. Reprinted as The Case For a 100 Percent Gold Dollar. Washington, DC: Libertarian Review Press, 1974, and Auburn, Ala: Mises Institute, 1991, 2005. © Mises Institute, 2005. Preface When this essay was published, nearly thirty years ago, America was in the midst of the Bretton Woods system, a Keynesian international monetary system that had been foisted upon the world by the United States and British governments in 1945. The Bretton Woods system was an international dollar standard masquerading as a “gold standard,” in order to lend the well- deserved prestige of the world’s oldest and most stable money, gold, to the increasingly inflated and depreciated dollar. But this post-World War II system was only a grotesque parody of a gold standard. In the pre-World War I “classical” gold standard, every currency unit, be it dollar, pound, franc, or mark, was defined as a certain unit of weight of gold. Thus, the “dollar” was defined as approximately 1/20 of an ounce of gold, while the pound sterling was defined as a little less than 1/4 of a gold ounce, thus fixing the exchange rate between the two (and between all other currencies) at the ratio of their weights.1 Since every national currency was defined as being a certain weight of gold, paper francs or dollars, or bank deposits were redeemable by the issuer, whether government or bank, in that weight of gold. -

Martin Van Buren: the Greatest American President

SUBSCRIBE NOW AND RECEIVE CRISIS AND LEVIATHAN* FREE! “The Independent Review does not accept “The Independent Review is pronouncements of government officials nor the excellent.” conventional wisdom at face value.” —GARY BECKER, Noble Laureate —JOHN R. MACARTHUR, Publisher, Harper’s in Economic Sciences Subscribe to The Independent Review and receive a free book of your choice* such as the 25th Anniversary Edition of Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American Government, by Founding Editor Robert Higgs. This quarterly journal, guided by co-editors Christopher J. Coyne, and Michael C. Munger, and Robert M. Whaples offers leading-edge insights on today’s most critical issues in economics, healthcare, education, law, history, political science, philosophy, and sociology. Thought-provoking and educational, The Independent Review is blazing the way toward informed debate! Student? Educator? Journalist? Business or civic leader? Engaged citizen? This journal is for YOU! *Order today for more FREE book options Perfect for students or anyone on the go! The Independent Review is available on mobile devices or tablets: iOS devices, Amazon Kindle Fire, or Android through Magzter. INDEPENDENT INSTITUTE, 100 SWAN WAY, OAKLAND, CA 94621 • 800-927-8733 • [email protected] PROMO CODE IRA1703 Martin Van Buren The Greatest American President —————— ✦ —————— JEFFREY ROGERS HUMMEL resident Martin Van Buren does not usually receive high marks from histori- ans. Born of humble Dutch ancestry in December 1782 in the small, upstate PNew York village of Kinderhook, Van Buren gained admittance to the bar in 1803 without benefit of higher education. Building on a successful country legal practice, he became one of the Empire State’s most influential and prominent politi- cians while the state was surging ahead as the country’s wealthiest and most populous. -

Collapsible Coliseum Cross of Gold

a'" VOLUME 18 PUBUSHED BY THE HYDE PARK HISTORICAL SOCIETY AUTUMN 1996 BY JAMES STRONKS In the swnmer of 1895 "The Greatest Building on Earth" (so said the flag on its roof) was going up on 63d Street, a block west of Stony Island Avenue. Inland Architect said "The Coliseum" was ~ the biggest building erected in America \ since the Columbian Exposition, and its ):4> statistics were indeed awesome. Longer than two football fields, it covered 51/2 acres of floor space and would seat 20,000 easily. Eleven enormous cantilever trusses spanned 218 feet of airspace, enclosing nearly a city block. A tower twenty stories high would dominate the neighborhood, its elevators rising to an observatory/cafe, with a roof-garden music-hall atop that, and at the pinnacle a giant electric searchlight visible for miles. The Coliseum's mammoth steel skeleton was all but completed ...and then it happened. At 11:10 p.m. on August 21 the immense framework collapsed. The appalling roar scared people off a standing train as far away as 47th Street. At dawn the next morning engineers with long faces inspected the ruins to determine the cause. Newspaper reporters licked their pencil points, eager to pin blame and expose a scandal. But THE there really wasn't any. The collapse was evidently caused by some 75 tons of lumber having been stacked on the roof COLLAPSIBLE so as to bear too heavily upon the last truss put into place, one which was not yet completely bolted into the structure COLISEUM as a whole. There was no scandal in the AND THE design, declared American Architect and Building N ews (Boston): "Both architect and engineer bear names of the best CROSS OF GOLD repute in the country." Just the same, it did not name them. -

The Historic Failure of the Chicago School of Antitrust Mark Glick

Antitrust and Economic History: The Historic Failure of the Chicago School of Antitrust Mark Glick1 Working Paper No. 95 May 2019 ABSTRACT This paper presents an historical analysis of the antitrust laws. Its central contention is that the history of antitrust can only be understood in light of U.S. economic history and the succession of dominant economic policy regimes that punctuated that history. The antitrust laws and a subset of other related policies have historically focused on the negative consequences resulting from the rise, expansion, and dominance of big business. Antitrust specifically uses competition as its tool to address these problems. The paper traces the evolution of the emergence, growth and expansion of big business over six economic eras: the Gilded Age, the Progressive Era, the New Deal, the post-World War II Era, the 1970s, and the era of neoliberalism. It considers three policy regimes: laissez-faire during the Gilded Age and the Progressive Era, the New Deal, policy regime from the Depression through the early 1970s, and the neoliberal policy regime that dominates today and includes the Chicago School of antitrust. The principal conclusion of the paper is that the activist antitrust policies associated with the New Deal that existed from the late 1 Professor, Department of Economics, University of Utah. Email: [email protected]. I would like to thank members of the University of Utah Competition Group, Catherine Ruetschlin, Marshall Steinbaum, and Ted Tatos for their help and input. I also benefited from suggestions and guidance from Gérard Duménil’s 2019 seminar on economic history at the University of Utah. -

William Jennings Bryan and His Opposition to American Imperialism in the Commoner

The Uncommon Commoner: William Jennings Bryan and his Opposition to American Imperialism in The Commoner by Dante Joseph Basista Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the History Program YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY August, 2019 The Uncommon Commoner: William Jennings Bryan and his Opposition to American Imperialism in The Commoner Dante Joseph Basista I hereby release this thesis to the public. I understand that this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: Dante Basista, Student Date Approvals: Dr. David Simonelli, Thesis Advisor Date Dr. Martha Pallante, Committee Member Date Dr. Donna DeBlasio, Committee Member Date Dr. Salvatore A. Sanders, Dean of Graduate Studies Date ABSTRACT This is a study of the correspondence and published writings of three-time Democratic Presidential nominee William Jennings Bryan in relation to his role in the anti-imperialist movement that opposed the US acquisition of the Philippines, Guam and Puerto Rico following the Spanish-American War. Historians have disagreed over whether Bryan was genuine in his opposition to an American empire in the 1900 presidential election and have overlooked the period following the election in which Bryan’s editorials opposing imperialism were a major part of his weekly newspaper, The Commoner. The argument is made that Bryan was authentic in his opposition to imperialism in the 1900 presidential election, as proven by his attention to the issue in the two years following his election loss. -

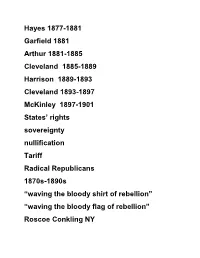

List for 202 First Exam

Hayes 1877-1881 Garfield 1881 Arthur 1881-1885 Cleveland 1885-1889 Harrison 1889-1893 Cleveland 1893-1897 McKinley 1897-1901 States’ rights sovereignty nullification Tariff Radical Republicans 1870s-1890s “waving the bloody shirt of rebellion” “waving the bloody flag of rebellion” Roscoe Conkling NY James G. Blaine Maine “Millionnaires’ Club” “the Railroad Lobby” 1. Conservative Rep party in control 2. Economy fluctuates a. Poor economy, prosperity, depression b. 1873 1893 1907 1929 c. Significant technological advances 3. Significant social changes 1876 Disputed Election of 1876 Rep- Rutherford B. Hayes Ohio Dem-Samuel Tilden NY To win 185 Tilden 184 + 1 Hayes 165 + 20 Fl SC La Oreg January 1877 Electoral Commission of 15 5 H, 5S, 5SC 7 R, 7 D, 1LR 8 to 7 Compromise of 1877 1. End reconstruction April 30, 1877 2. Appt s. Dem. Cab David Key PG 3. Support funds for internal improvements in the South Hayes 1877-1881 “ole 8 and 7 Hayes” “His Fraudulency” Carl Schurz Wm Everts Civil Service Reform Chester A. Arthur Great Strike of 1877 Resumption Act 1875 specie Bland Allison Silver Purchase Act 1878 16:1 $2-4 million/mo Silver certificates 1880 James G. Blaine Blaine Halfbreeds Rep James A Garfield Ohio Chester A. Arthur Roscoe Conkling Conkling Stalwarts Grant Dem Winfield Scott Hancock PA Greenback Party James B. Weaver Iowa Battle of the 3 Generals 1881 Arthur Pendleton Civil Service Act 1883 Chicago and Boston 1884 Election Rep. Blaine of Maine Mugwumps Dem. Grover Cleveland NY “Rum, Romanism and Rebellion” 1885-1889 Character Union Veterans Grand Army of the Republic GAR LQC Lamar S of Interior 1862 union pension 1887 Dependent Pension Bill Interstate Commerce Act 1887 ICC Pooling, rebates, drawbacks Prohibit discrimination John D. -

Mere Libertarianism: Blending Hayek and Rothbard

Mere Libertarianism: Blending Hayek and Rothbard Daniel B. Klein Santa Clara University The continued progress of a social movement may depend on the movement’s being recognized as a movement. Being able to provide a clear, versatile, and durable definition of the movement or philosophy, quite apart from its justifications, may help to get it space and sympathy in public discourse. 1 Some of the most basic furniture of modern libertarianism comes from the great figures Friedrich Hayek and Murray Rothbard. Like their mentor Ludwig von Mises, Hayek and Rothbard favored sweeping reductions in the size and intrusiveness of government; both favored legal rules based principally on private property, consent, and contract. In view of the huge range of opinions about desirable reform, Hayek and Rothbard must be regarded as ideological siblings. Yet Hayek and Rothbard each developed his own ideas about liberty and his own vision for a libertarian movement. In as much as there are incompatibilities between Hayek and Rothbard, those seeking resolution must choose between them, search for a viable blending, or look to other alternatives. A blending appears to be both viable and desirable. In fact, libertarian thought and policy analysis in the United States appears to be inclined toward a blending of Hayek and Rothbard. At the center of any libertarianism are ideas about liberty. Differences between libertarianisms usually come down to differences between definitions of liberty or between claims made for liberty. Here, in exploring these matters, I work closely with the writings of Hayek and Rothbard. I realize that many excellent libertarian philosophers have weighed in on these matters and already said many of the things I say here. -

Uniting Mugwumps and the Masses: the Role of Puck in Gilded Age Politics, 1880-1884

Uniting Mugwumps and the Masses: The Role of Puck in Gilded Age Politics, 1880-1884 Daniel Henry Backer McLean, Virginia B.A., University of Notre Dame, 1994 A Thesis presented to 1he Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of English University of Virginia August 1996 WARNING! The document you now hold in your hands is a feeble reproduction of an experiment in hypertext. In the waning years of the twentieth century, a crude network of computerized information centers formed a system called the Internet; one particular format of data retrieval combined text and digital images and was known as the World Wide Web. This particular project was designed for viewing through Netscape 2.0. It can be found at http://xroads.virginia.edu/~MA96/PUCK/ If you are able to locate this Website, you will soon realize it is a superior resource for the presentation of such a highly visual magazine as Puck. 11 Table of Contents Introduction 1 I) A Brief History of Cartoons 5 II) Popular and Elite Political Culture 13 III) A Popular Medium 22 "Our National Dog Show" 32 "Inspecting the Democratic Curiosity Shop" 35 Caricature and the Carte-de-Viste 40 The Campaign Against Grant 42 EndNotes 51 Bibliography 54 1 wWhy can the United States not have a comic paper of its own?" enquired E.L. Godkin of The Nation, one of the most distinguished intellectual magazines of the Gilded Age. America claimed a host of popular and insightful raconteurs as its own, from Petroleum V.