A Philological Approach to Buddhism, K.R. Norman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nomenclature of Post Graduate Courses in Buddhist Studies

UNIVERSITY OF JAMMU CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM FORPOST GRADUATE PROGRAMME IN THE DEPARTMENT OF BUDDHIST STUDIES W.E.F. THE ACADEMIC YEAR 2020-21 Nomenclature of Post Graduate Courses in Buddhist Studies Nomenclature of courses will be done in such a way that the course code will consist of eleven characters. The first character ‘P’ stands for Post Graduate. The second character ‘S’ stands for Semester. Next two characters will denote the Subject Code. Subject Subject Code Buddhist Studies BS Next character will signify the nature of the course. T- Theory Course D- Project based Courses leading to dissertation (e.g. Major, Minor, Mini Project etc.) L- Training S- Independent Study V- Special Topic Lecture Courses Tu- Tutorial The succeeding character will denote whether the course is compulsory “C” or Elective “E”. The next character will denote the Semester Number. For example: 1 will denote Semester— I, and 2 will denote Semester— II Last two characters will denote the paper Number. Nomenclature of P G Courses PSBSTC101 P POST GRADUATE S SEMESTER BS BUDDHIST STUDIES (SUBJECT CODE) T THEORY (NATURE OF COURSE) C COMPULSORY 1 SEMESTER NUMBER 01 PAPER NUMBER O OPEN 1 Semester wise Distribution of Courses and Credits SEMESTER- I (December 2018, 2019, 2020 & 2021) Course code Paper Credits PSBSTC101 History of Buddhism in India 6 PSBSTC102 Fundamentals of Buddhist Philosophy 6 PSBSTC103 Pali Language and History 6 PSBSTC104 Selected Pali Sutta Texts 6 SEMESTER- II (May 2019, 2020 and 2021) Course code Paper Credits PSBSTC201 Vinaya -

Hinduism and Hindu Philosophy

Essays on Indian Philosophy UNIVE'aSITY OF HAWAII Uf,FU:{ Essays on Indian Philosophy SHRI KRISHNA SAKSENA UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII PRESS HONOLULU 1970 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 78·114209 Standard Book Number 87022-726-2 Copyright © 1970 by University of Hawaii Press All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America Contents The Story of Indian Philosophy 3 Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy 18 Testimony in Indian Philosophy 24 Hinduism 37 Hinduism and Hindu Philosophy 51 The Jain Religion 54 Some Riddles in the Behavior of Gods and Sages in the Epics and the Puranas 64 Autobiography of a Yogi 71 Jainism 73 Svapramanatva and Svapraka!;>atva: An Inconsistency in Kumarila's Philosophy 77 The Nature of Buddhi according to Sankhya-Yoga 82 The Individual in Social Thought and Practice in India 88 Professor Zaehner and the Comparison of Religions 102 A Comparison between the Eastern and Western Portraits of Man in Our Time 117 Acknowledgments The author wishes to make the following acknowledgments for permission to reprint previously published essays: "The Story of Indian Philosophy," in A History of Philosophical Systems. edited by Vergilius Ferm. New York:The Philosophical Library, 1950. "Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy," previously published as "Are There Any Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy?" in The Philosophical Quarterly. "Testimony in Indian Philosophy," previously published as "Authority in Indian Philosophy," in Ph ilosophyEast and West. vo!.l,no. 3 (October 1951). "Hinduism," in Studium Generale. no. 10 (1962). "The Jain Religion," previously published as "Jainism," in Religion in the Twentieth Century. edited by Vergilius Ferm. -

Kesariya Stupa: Recently Excavated Architectural Marvel

Proceeding of the International Conference on Archaeology, History and Heritage, Vol. 1, 2019, pp. 27-31 Copyright © 2019 TIIKM ISSN 2651-0243online DOI: https://doi.org/10.17501/26510243.2019.1103 KESARIYA STUPA: RECENTLY EXCAVATED ARCHITECTURAL MARVEL Ishani Sinha Deccan College Post Graduate and Research Institute, Pune, Maharashtra, India Abstract: The early Buddhist texts record that Buddha announced his approaching nirvana to the monks at vaishali. According to historical traditions, monks followed him as he departed from Vaishali after delivering the last sermon. Buddha persuaded them to return back and presented his alms-bowl to them as memorial. To commemorate that event a stupa was built there which is now identified with kesariya stupa (in Bihar) and which falls en route from Vaishali to Kushinagar (in eastern Uttar Pradesh) where Buddha attained nirvana. This stupa finds reference in the travelogues of Fa Xian and Xuan Zang, the two celebrated Chinese monks of fifth and seventh century CE respectively. Briefly mentioned by Alexander Cunningham in 1861-62, the stupa mound at Kesariya was subjected to meticulous excavation from 1997-98 onwards by Archaeological Survey of India which is still continuing. The unearthed brick stupa is datable to Gupta period (5th-6th century CE) although an earlier phase datable to Sunga-Satavahana period (1st-2nd century CE) was also traced below it. The stupa is a six terraced structure with a cylindrical drum atop and a group of cells, with intervening polygonal designs, on each terrace enshrining stucco image of Buddha. With an extant height of about 31.5 metres and a diameter of about 123 metres, it is undoubtedly one of the tallest and most voluminous stupas in India. -

Suttanipata Commentary

Suttanipāta Commentary Translated by the Burma Piṭaka Association Suttanipāta Commentary Translated by the Burma Piṭaka Association Edited by Bhikkhu Pesala for the © Association for Insight Meditation November 2018 All Rights Reserved You may print copies for your personal use or for Free Dis�ibution as a Gift of the Dhamma. Please do not host it on your own web site, but link to the source page so that any updates or corrections will be available to all. Contents Editor’s Foreword.......................................................................................................vii Translator’s Preface....................................................................................................viii I. Uragavagga (Snake Chapter).....................................................................................ix 1. Uraga Sutta Vaṇṇanā......................................................................................ix 2. Dhaniya Sutta Vaṇṇanā...................................................................................x 3. Khaggavisāṇa Sutta Vaṇṇanā.........................................................................xi 4. Kasībhāradvāja Sutta Vaṇṇanā.......................................................................xi 5. Cunda Sutta Vaṇṇanā....................................................................................xii 6. Parābhava Sutta Vaṇṇanā..............................................................................xii 7. Aggikabhāradvāja Sutta Vaṇṇanā................................................................xiii -

A Study of the Śarīrārthagāthā in the Yogācārabhūmi

A STUDY OF THE ŚARĪRĀRTHAGĀTHĀ IN THE YOGĀCĀRABHŪMI A dissertation presented by Hsu-Feng Lee to The Department of Indian Subcontinental Studies School of Languages and Cultures Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences A thesis submitted in fulfilment of requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Sydney March 2017 Abstract The Śarīrārthagāthā (Tǐyì qiétā 體義伽他;‘dus pa’i don gyi tshigs su bcad pa) is a collection of canonical verses with accompanying commentary in the Yogācārabhūmi (Yúqié shī dì lùn 瑜伽師地論; rnal 'byor spyod pa'i sa), an encyclopedic text of India’s major Mahāyāna philosophical school. To date the Śarīrārthagāthā has not attracted much scholarly research and many interesting aspects have hitherto gone unnoticed that are worthy of further investigation. Some researchers have identified the sources of these verses, and a study by Enomoto (1989) is the most complete. In this dissertation, I have carried out further analyses based on the results found by these researchers. The initial topics are the place of the Śarīrārthagāthā verses in the formation of Buddhist texts (especially, aṅga classification) and the reason why early verses in particular were collected in the Śarīrārthagāthā. The work of Yìnshùn has provided significant information for the investigation of the above issues. He investigated the development and relationship between aṅga and Āgamas from texts during the period of early Buddhism to Mahāyāna. Moreover, the distinctive characteristics of the Śarīrārthagāthā verses have been investigated through a comparison with their parallels in other texts, with the aim of assessing the school affiliation of these texts. -

The Nibbāna of Mahākassapa the Elder: Notes on a Buddhist Narrative Transmitted in Thai and Lao Literature François Lagirarde

The Nibbāna of Mahākassapa the Elder: Notes on a Buddhist Narrative Transmitted in Thai and Lao Literature François Lagirarde To cite this version: François Lagirarde. The Nibbāna of Mahākassapa the Elder: Notes on a Buddhist Narrative Transmit- ted in Thai and Lao Literature. Buddhist Legacies in Mainland Southeast Asia, 2006. hal-01955848 HAL Id: hal-01955848 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01955848 Submitted on 21 Dec 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. François Lagirarde The Nibbāna of Mahākassapa the Elder: Notes on a Buddhist Narrative Transmitted in Thai and Lao Literature THIS LEGEND OF MAHākassapa’S NIBBāNA from his last morning, to his failed farewell to King Ajātasattu, to his parinibbāna in the evening, to his ultimate “meeting” with Metteyya thousands of years later—is well known in Thailand and Laos although it was not included in the Pāli tipiṭaka or even mentioned in the commentaries or sub-commentaries. In fact, the texts known as Mahākassapatheranibbāna (the Nibbāna of Mahākassapa the Elder) represent only one among many other Nibbāna stories known in Thai-Lao Buddhist literature. In this paper I will attempt to show that the textual tradition dealing with the last moments of many disciples or “Hearers” of the Buddha—with Mahākassapa as the first one—became a rich, vast, and well preserved genre at least in the Thai world. -

Download Download

Transcultural Studies 2016.1 121 Local Agency in Global Movements: Negotiating Forms of Buddhist Cosmopolitanism in the Young Men’s Buddhist Associations of Darjeeling and Kalimpong Kalzang Dorjee Bhutia, Grinnell College Introduction Darjeeling and Kalimpong have long played important roles in the development of global knowledge about Tibetan and Himalayan religions.1 While both trade centres became known throughout the British empire for their recreational opportunities, favourable climate, and their famous respective exports of Darjeeling tea and Kalimpong wool, they were both the centres of a rich, dynamic, and as time went on, increasingly hybrid cultural life. Positioned as they were on the frontier between the multiple states of India, Bhutan, Sikkim, Tibet, and Nepal, as well as the British and Chinese empires, Darjeeling and Kalimpong were also both home to multiple religious traditions. From the mid-nineteenth century onwards, Christian missionaries from Britain developed churches and educational institutions there in an attempt to gain a foothold in the hills. Their task was not an easy one, due to the strength of local traditions and the political and economic dominance of local Tibetan-derived Buddhist monastic institutions, which functioned as satellite institutions and commodity brokers for the nearby Buddhist states of Tibet, Sikkim, and Bhutan. British colonial administrators and scholars from around the world took advantage of the easy proximity of these urban centres for their explorations, and considered them as museums of living Buddhism. While Tibet remained closed for all but a lucky few, other explorers, Orientalist 1 I would like to thank the many people who contributed to this article, especially Pak Tséring’s family and members of past and present YMBA communities and their families in Darjeeling, Kalimpong, and Sikkim; L. -

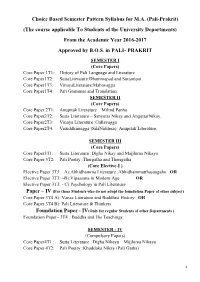

Pali-Prakrit) (The Course Applicable to Students of the University Departments) from the Academic Year 2016-2017 Approved by B.O.S

Choice Based Semester Pattern Syllabus for M.A. (Pali-Prakrit) (The course applicable To Students of the University Departments) From the Academic Year 2016-2017 Approved by B.O.S. in PALI- PRAKRIT SEMESTER I (Core Papers) Core Paper 1T1: History of Pali Language and Literature Core Paper1T2: SuttaLiterature:Dhammapad and Suttanipat Core Paper1T3: VinayaLiterature:Mahavagga. Core Paper1T4: Pali Grammar and Translation SEMESTER II (Core Papers) Core Paper 2T1: Anupitak Literature – Milind Panho Core Paper2T2: Sutta Literature – Sanyutta Nikay and AnguttarNikay. Core Paper2T3: Vinaya Literature :Cullavagga Core Paper2T4: Visuddhimagga (SilaNiddesa): Anupitak Literature. SEMESTER III (Core Papers) Core Paper3T1: Sutta Literature :Digha Nikay and Majjhima Nikaya Core Paper 3T2: Pali Poetry :Thergatha and Therigatha. (Core Elective-I ) Elective Paper 3T3: –A):Abhidhamma Literature :Abhidhammatthasangaho OR Elective Paper 3T3: –B):Vipassana in Modern Age OR Elective Paper 3T3: - C) Psychology in Pali Literature Paper – IV (For those Students who do not adopt the foundation Paper of other subject) Core Paper 3T4 A): Vansa Literature and Buddhist History OR Core Paper 3T4 B): Pali Literature & Thinkers Foundation Paper - IV(Only for regular Students of other Departments ) Foundation Paper– 3T4 : Buddha and His Teachings SEMESTER - IV (Compulsory Papers) Core Paper4T1 : Sutta Literature : Digha Nikaya – Mijjhima Nikaya Core Paper 4T2: Pali Poetry :Khuddaka Nikay (Pali Gatha) 1 (Core Elective-II ) Elective Paper 4T3: –A) Vinaypitaka – Patimokkha OR Elective Paper 4T3: –B) Modern Pali Literature OR Elective Paper 4T3: - C) Atthakatha Literature Paper – IV (For those Students who do not adopt the foundation Paper of other subject) Core Paper 4T4: -A): Comparative Linguistics and Essay OR Core Paper 4T4: -B): Propagation of Pali Literature Foundation Paper - IV(Only for regular Students of other Departments ) Foundation Paper - 4T4: - Pali Language and Literature University of Rashtrasant Tukadoji Maharaj Nagpur M.A. -

In Buddhist Studies

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar University of Social Sciences Dr. Ambedkar Nagar (Mhow), Indore (M.P.) M.A. (MASTER OF ARTS) IN BUDDHIST STUDIES SYLLABUS 2018 Course started from session: 2018-19 M.A. in Buddhist Studies, Session: 2018-19, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar University of Social Sciences, Mhow Page 1 of 19 ikB~;Øe ifjp; (Introduction of the Course) ,e-,- ¼ckS) v/;;u½ ,e-,- (ckS) v/;;u) ikB~;Øe iw.kZdkfyd f}o"khZ; ikB~;Øe gSA ;g ikB~;Øe pkj l=k)ksZa (Semesters) rFkk nks o"kksZ ds Øe esa foHkDr gSA ÁFke o"kZ esa l=k)Z I o II rFkk f}rh; o"kZ esa l=k)Z III o IV dk v/;kiu fd;k tk;sxkA ikB~;dze ds vUrxZr O;k[;kuksa] laxksf"B;ksa] izk;ksfxd&dk;ksZ] V;wVksfj;Yl rFkk iznÙk&dk;ksZ (Assignments) vkfn ds ek/;e ls v/;kiu fd;k tk;sxkA izR;sd l=k)Z esa ckS) v/;;u fo"k; ds pkj&pkj iz'u&i= gksaxsA izR;sd iz'u&i= ds fy, ik¡p bdkb;k¡ (Units) rFkk 3 ØsfMV~l fu/kkZfjr gksaxsA vad&foHkktu ¼izfr iz'u&i=½ 1- lS)kfUrd&iz'u & 60 (Theoretical Questions) 2- vkUrfjd& ewY;kadu & 40 (Internal Assessment) e/;&l=k)Z ewY;kadu + x`g dk;Z + d{kk esa laxks"Bh i= izLrqfr ¼20 + 10+ 10½ ;ksx % & 100 ijh{kk ek/;e % ckS) v/;;u fo"k; fgUnh ,oa vaxzsth nksuksa ek/;e esa lapkfyr fd;k tk,xk A lS)kfUrd iz'u&i= dk Lo#i (Pattern of Theatrical Question paper) nh?kksZŸkjh; iz'u 4 x 10 & 20 vad y?kqŸkjh; iz'u 6 x 5 & 30 vad fVIi.kh ys[ku 2 x 5 & 10 vad ;ksx & 60 M.A. -

A Philological Approach to Buddhism

THE BUDDHIST FORUM, VOLUME V A PHILOLOGICAL APPROACH TO BUDDHISM The Bukkyō Dendō Kyōkai Lectures 1994 K.R. Norman THE INSTITUTE OF BUDDHIST STUDIES, TRING, UK THE INSTITUTE OF BUDDHIST STUDIES, BERKELEY, USA 2012 First published by the School of Oriental and African Studies (University of London), 1997 © Online copyright 2012 belongs to: The Institute of Buddhist Studies, Tring, UK & The Institute of Buddhist Studies, Berkeley, USA British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data ISBN 0-7286-0276-8 ISSN 0959-0595 CONTENTS The online pagination 2012 corresponds to the hard copy pagination 1997 Foreword.........................................................................................................................................vii Abbreviations...................................................................................................................................ix Bibliography....................................................................................................................................xi I Buddhism and Philology............................................................................................................1 II Buddhism and its Origins.........................................................................................................21 III Buddhism and Oral Tradition.................................................................................................41 IV Buddhism and Regional Dialects............................................................................................59 -

Seven Papers by Subhuti with Sangharakshita

SEVEN PAPERS by SANGHARAKSHITA and SUBHUTI 2 SEVEN PAPERS May the merit gained In my acting thus Go to the alleviation of the suffering of all beings. My personality throughout my existences, My possessions, And my merit in all three ways, I give up without regard to myself For the benefit of all beings. Just as the earth and other elements Are serviceable in many ways To the infinite number of beings Inhabiting limitless space; So may I become That which maintains all beings Situated throughout space, So long as all have not attained To peace. SEVEN PAPERS 3 SEVEN PAPERS BY SANGHARAKSHITA AND SUBHUTI 2ND EDITION (2.01) with thanks to: Sangharakshita and Subhuti, for the talks and papers Lokabandhu, for compiling this collection lulu.com, the printers An A5 format suitable for iPads is available from Lulu; for a Kindle version please contact Lokabandhu. This is a not-for-profit project, the book being sold at the per-copy printing price. 4 SEVEN PAPERS Contents Introduction 8 What is the Western Buddhist Order? 9 Revering and Relying upon the Dharma 39 Re-Imagining The Buddha 69 Buddhophany 123 Initiation into a New Life: the Ordination Ceremony in Sangharakshita's System oF Spiritual Practice 127 'A supra-personal force or energy working through me': The Triratna Buddhist Community and the Stream of the Dharma 151 The Dharma Revolution and the New Society 205 A Buddhist Manifesto: the Principles oF the Triratna Buddhist Community 233 Index 265 Notes 272 SEVEN PAPERS 5 6 SEVEN PAPERS SEVEN PAPERS 7 Introduction This book presents a collection of seven recent papers by either Sangharakshita or Subhuti, or both working together. -

Way of Practice Leading to Nibbāna Volume Iv

“namo tassabhagavato arahato sammasambudhassa” NIBBĀNAGAMINIPATIPADA WAY OF PRACTICE LEADING TO NIBBĀNA VOLUME IV PAGE 442-463 BY PA-AUK TAWYA SAYADAW TRANSLATED BY U MYINT SWE (M.A London) NIBBĀNAGAMINIPATIPADA (PA-AUK TAWYA SAYADAW) 2 Page- 442 “Learning the Scriptures just to maintain (memorize) them:” Bhandāgārika- Pariyatti' means ‘the Buddhist scriptures learnt (studied) by the Arahats , whose mind is free from the mental defilements. They have already known the truth of Suffering ( dukkhasacca ), that is, the five aggregates by the three-fold knowledge, have already abandoned (eliminated) all mental defilements and kammic forces, called samudaya.sacca' have already developed the truth of Eightfold path, called 'Magga.sacca' and have already realized Nibbāna the Truth of Cessation of Craving, called Nirodha.sacca' , with their Path-and-Fruition knowledges. Those Arahats , 1- have already known the five Aggregates of Clinging; called Dukkha.sacca; existing in eleven modes (of), such as 'past, future, present' etc, by their insight knowledge of three kinds, viz, 'Ñāta, Tirana and Pahāna' . 2- have already abandoned (eliminated, uprooted) all the defilements and kammic forces, by their path knowledges. 3- have already developed the Eightfold path, called 'Magga.sacca' . 4- have already realized Nibbāna , the Unconditioned and Peaceful element, called 'Nirodha.sacca' , by their Arahatta-Fruition knowledge. Therefore, the Arahats' learning the Buddhist scriptures is just to memorize the Canonical texts, to maintain the succession of Dhammas , and to main the lineage (family) of the Buddha. Thus, their learning of the Buddhist scriptures is termed 'Bhandāgārika. Pariyatti'. When there arose (took place) the hardships such as the hunger and thirst etc., and the famous and eminent Reverend monks could not live (stay) together in one place, a worldling monk living by daily going round for alms, studied (learnt) the Buddhist scriptures with good purpose (intention): "Let the Buddhn's sweet teachings (Buddhist scriptures) not disappear (or last for long).