Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nomenclature of Post Graduate Courses in Buddhist Studies

UNIVERSITY OF JAMMU CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM FORPOST GRADUATE PROGRAMME IN THE DEPARTMENT OF BUDDHIST STUDIES W.E.F. THE ACADEMIC YEAR 2020-21 Nomenclature of Post Graduate Courses in Buddhist Studies Nomenclature of courses will be done in such a way that the course code will consist of eleven characters. The first character ‘P’ stands for Post Graduate. The second character ‘S’ stands for Semester. Next two characters will denote the Subject Code. Subject Subject Code Buddhist Studies BS Next character will signify the nature of the course. T- Theory Course D- Project based Courses leading to dissertation (e.g. Major, Minor, Mini Project etc.) L- Training S- Independent Study V- Special Topic Lecture Courses Tu- Tutorial The succeeding character will denote whether the course is compulsory “C” or Elective “E”. The next character will denote the Semester Number. For example: 1 will denote Semester— I, and 2 will denote Semester— II Last two characters will denote the paper Number. Nomenclature of P G Courses PSBSTC101 P POST GRADUATE S SEMESTER BS BUDDHIST STUDIES (SUBJECT CODE) T THEORY (NATURE OF COURSE) C COMPULSORY 1 SEMESTER NUMBER 01 PAPER NUMBER O OPEN 1 Semester wise Distribution of Courses and Credits SEMESTER- I (December 2018, 2019, 2020 & 2021) Course code Paper Credits PSBSTC101 History of Buddhism in India 6 PSBSTC102 Fundamentals of Buddhist Philosophy 6 PSBSTC103 Pali Language and History 6 PSBSTC104 Selected Pali Sutta Texts 6 SEMESTER- II (May 2019, 2020 and 2021) Course code Paper Credits PSBSTC201 Vinaya -

Kesariya Stupa: Recently Excavated Architectural Marvel

Proceeding of the International Conference on Archaeology, History and Heritage, Vol. 1, 2019, pp. 27-31 Copyright © 2019 TIIKM ISSN 2651-0243online DOI: https://doi.org/10.17501/26510243.2019.1103 KESARIYA STUPA: RECENTLY EXCAVATED ARCHITECTURAL MARVEL Ishani Sinha Deccan College Post Graduate and Research Institute, Pune, Maharashtra, India Abstract: The early Buddhist texts record that Buddha announced his approaching nirvana to the monks at vaishali. According to historical traditions, monks followed him as he departed from Vaishali after delivering the last sermon. Buddha persuaded them to return back and presented his alms-bowl to them as memorial. To commemorate that event a stupa was built there which is now identified with kesariya stupa (in Bihar) and which falls en route from Vaishali to Kushinagar (in eastern Uttar Pradesh) where Buddha attained nirvana. This stupa finds reference in the travelogues of Fa Xian and Xuan Zang, the two celebrated Chinese monks of fifth and seventh century CE respectively. Briefly mentioned by Alexander Cunningham in 1861-62, the stupa mound at Kesariya was subjected to meticulous excavation from 1997-98 onwards by Archaeological Survey of India which is still continuing. The unearthed brick stupa is datable to Gupta period (5th-6th century CE) although an earlier phase datable to Sunga-Satavahana period (1st-2nd century CE) was also traced below it. The stupa is a six terraced structure with a cylindrical drum atop and a group of cells, with intervening polygonal designs, on each terrace enshrining stucco image of Buddha. With an extant height of about 31.5 metres and a diameter of about 123 metres, it is undoubtedly one of the tallest and most voluminous stupas in India. -

The Nibbāna of Mahākassapa the Elder: Notes on a Buddhist Narrative Transmitted in Thai and Lao Literature François Lagirarde

The Nibbāna of Mahākassapa the Elder: Notes on a Buddhist Narrative Transmitted in Thai and Lao Literature François Lagirarde To cite this version: François Lagirarde. The Nibbāna of Mahākassapa the Elder: Notes on a Buddhist Narrative Transmit- ted in Thai and Lao Literature. Buddhist Legacies in Mainland Southeast Asia, 2006. hal-01955848 HAL Id: hal-01955848 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01955848 Submitted on 21 Dec 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. François Lagirarde The Nibbāna of Mahākassapa the Elder: Notes on a Buddhist Narrative Transmitted in Thai and Lao Literature THIS LEGEND OF MAHākassapa’S NIBBāNA from his last morning, to his failed farewell to King Ajātasattu, to his parinibbāna in the evening, to his ultimate “meeting” with Metteyya thousands of years later—is well known in Thailand and Laos although it was not included in the Pāli tipiṭaka or even mentioned in the commentaries or sub-commentaries. In fact, the texts known as Mahākassapatheranibbāna (the Nibbāna of Mahākassapa the Elder) represent only one among many other Nibbāna stories known in Thai-Lao Buddhist literature. In this paper I will attempt to show that the textual tradition dealing with the last moments of many disciples or “Hearers” of the Buddha—with Mahākassapa as the first one—became a rich, vast, and well preserved genre at least in the Thai world. -

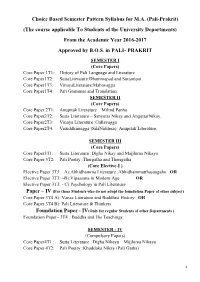

Pali-Prakrit) (The Course Applicable to Students of the University Departments) from the Academic Year 2016-2017 Approved by B.O.S

Choice Based Semester Pattern Syllabus for M.A. (Pali-Prakrit) (The course applicable To Students of the University Departments) From the Academic Year 2016-2017 Approved by B.O.S. in PALI- PRAKRIT SEMESTER I (Core Papers) Core Paper 1T1: History of Pali Language and Literature Core Paper1T2: SuttaLiterature:Dhammapad and Suttanipat Core Paper1T3: VinayaLiterature:Mahavagga. Core Paper1T4: Pali Grammar and Translation SEMESTER II (Core Papers) Core Paper 2T1: Anupitak Literature – Milind Panho Core Paper2T2: Sutta Literature – Sanyutta Nikay and AnguttarNikay. Core Paper2T3: Vinaya Literature :Cullavagga Core Paper2T4: Visuddhimagga (SilaNiddesa): Anupitak Literature. SEMESTER III (Core Papers) Core Paper3T1: Sutta Literature :Digha Nikay and Majjhima Nikaya Core Paper 3T2: Pali Poetry :Thergatha and Therigatha. (Core Elective-I ) Elective Paper 3T3: –A):Abhidhamma Literature :Abhidhammatthasangaho OR Elective Paper 3T3: –B):Vipassana in Modern Age OR Elective Paper 3T3: - C) Psychology in Pali Literature Paper – IV (For those Students who do not adopt the foundation Paper of other subject) Core Paper 3T4 A): Vansa Literature and Buddhist History OR Core Paper 3T4 B): Pali Literature & Thinkers Foundation Paper - IV(Only for regular Students of other Departments ) Foundation Paper– 3T4 : Buddha and His Teachings SEMESTER - IV (Compulsory Papers) Core Paper4T1 : Sutta Literature : Digha Nikaya – Mijjhima Nikaya Core Paper 4T2: Pali Poetry :Khuddaka Nikay (Pali Gatha) 1 (Core Elective-II ) Elective Paper 4T3: –A) Vinaypitaka – Patimokkha OR Elective Paper 4T3: –B) Modern Pali Literature OR Elective Paper 4T3: - C) Atthakatha Literature Paper – IV (For those Students who do not adopt the foundation Paper of other subject) Core Paper 4T4: -A): Comparative Linguistics and Essay OR Core Paper 4T4: -B): Propagation of Pali Literature Foundation Paper - IV(Only for regular Students of other Departments ) Foundation Paper - 4T4: - Pali Language and Literature University of Rashtrasant Tukadoji Maharaj Nagpur M.A. -

Sikkim Major District Roads Upgradation Project: Project

Project Readiness Financing Project Administration Manual Project Number: 52159-003 Loan Number: {PRFXXXX} May 2021 India: Sikkim Major District Roads Upgradation Project CONTENTS I. IMPLEMENTATION PLAN 1 A. Overall Implementation Plan 1 II. PROJECT MANAGEMENT ARRANGEMENTS 2 A. Project Implementation Organizations: Roles and Responsibilities 2 B. Key Persons Involved in Implementation 3 III. COSTS AND FINANCING 5 A. Key Assumptions 5 B. Allocation and Withdrawal of Loan Proceeds 5 C. Detailed Cost Estimates by Expenditure Category and Financier 6 D. Detailed Cost Estimates by Year 7 E. Contract and Disbursement S-Curve 8 IV. FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT 8 A. Financial Management Assessment 8 B. Disbursement 10 C. Accounting 11 D. Auditing and Public Disclosure 12 V. PROCUREMENT AND CONSULTING SERVICES 12 A. Advance Contracting and Retroactive Financing 13 B. Procurement of Consulting Services 13 C. Procurement of Goods and Civil Works 13 D. Procurement Plan 13 E. Consultant's Terms of Reference 13 VI. SAFEGUARDS 14 VII. PERFORMANCE MONITORING 14 A. Monitoring 14 B. Reporting 14 VIII. ANTICORRUPTION POLICY 15 IX. ACCOUNTABILITY MECHANISM 15 X. RECORD OF CHANGES TO THE PROJECT ADMINISTRATION MANUAL 15 APPENDIXES 1. Indicative list of Subprojects 16 2. Detailed Terms of Reference 17 Project Administration Manual for Project Readiness Financing Facility: Purpose and Process The project administration manual (PAM) for the project readiness financing (PRF) facility is an abridged version of the regular PAM of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and describes the essential administrative and management requirements to implement the PRF facility following the policies and procedures of the government and ADB. The PAM should include references to all available templates and instructions either by linking to relevant URLs or directly incorporating them in the PAM. -

In Buddhist Studies

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar University of Social Sciences Dr. Ambedkar Nagar (Mhow), Indore (M.P.) M.A. (MASTER OF ARTS) IN BUDDHIST STUDIES SYLLABUS 2018 Course started from session: 2018-19 M.A. in Buddhist Studies, Session: 2018-19, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar University of Social Sciences, Mhow Page 1 of 19 ikB~;Øe ifjp; (Introduction of the Course) ,e-,- ¼ckS) v/;;u½ ,e-,- (ckS) v/;;u) ikB~;Øe iw.kZdkfyd f}o"khZ; ikB~;Øe gSA ;g ikB~;Øe pkj l=k)ksZa (Semesters) rFkk nks o"kksZ ds Øe esa foHkDr gSA ÁFke o"kZ esa l=k)Z I o II rFkk f}rh; o"kZ esa l=k)Z III o IV dk v/;kiu fd;k tk;sxkA ikB~;dze ds vUrxZr O;k[;kuksa] laxksf"B;ksa] izk;ksfxd&dk;ksZ] V;wVksfj;Yl rFkk iznÙk&dk;ksZ (Assignments) vkfn ds ek/;e ls v/;kiu fd;k tk;sxkA izR;sd l=k)Z esa ckS) v/;;u fo"k; ds pkj&pkj iz'u&i= gksaxsA izR;sd iz'u&i= ds fy, ik¡p bdkb;k¡ (Units) rFkk 3 ØsfMV~l fu/kkZfjr gksaxsA vad&foHkktu ¼izfr iz'u&i=½ 1- lS)kfUrd&iz'u & 60 (Theoretical Questions) 2- vkUrfjd& ewY;kadu & 40 (Internal Assessment) e/;&l=k)Z ewY;kadu + x`g dk;Z + d{kk esa laxks"Bh i= izLrqfr ¼20 + 10+ 10½ ;ksx % & 100 ijh{kk ek/;e % ckS) v/;;u fo"k; fgUnh ,oa vaxzsth nksuksa ek/;e esa lapkfyr fd;k tk,xk A lS)kfUrd iz'u&i= dk Lo#i (Pattern of Theatrical Question paper) nh?kksZŸkjh; iz'u 4 x 10 & 20 vad y?kqŸkjh; iz'u 6 x 5 & 30 vad fVIi.kh ys[ku 2 x 5 & 10 vad ;ksx & 60 M.A. -

Bulletin of Tibetology

Bulletin of Tibetology VOLUME 45 NO. 2 VOLUME 46 NO. 1 Special Issue 2010 The Bulletin of Tibetology seeks to serve the specialist as well as the general reader with an interest in the field of study. The motif portraying the Stupa on the mountains suggests the dimensions of the field. Patron HON’BLE SHRINIVAS PATIL, THE GOVERNOR OF SIKKIM Advisor TASHI DENSAPA, DIRECTOR NIT Editorial Board FRANZ-KARL EHRHARD ACHARYA SAMTEN GYATSO SAUL MULLARD BRIGITTE STEINMANN TASHI TSERING MARK TURIN ROBERTO VITALI Guest Editor for Present Issue SAUL MULLARD Editor ANNA BALIKCI-DENJONGPA Assistant Editors TSULTSEM GYATSO ACHARYA THUPTEN TENZING The Bulletin of Tibetology is published bi-annually by the Director, Namgyal Institute of Tibetology, Gangtok, Sikkim. Annual subscription rates: South Asia, Rs150. Overseas, $20. Correspondence concerning bulletin subscriptions, changes of address, missing issues etc., to: Administrative Officer, Namgyal Institute of Tibetology, Gangtok 737102, Sikkim, India ([email protected]). Editorial correspondence should be sent to the Editor at the same address. Submission guidelines. We welcome submission of articles on any subject of the religion, history, language, art, and culture of the people of the Tibetan cultural area and the Buddhist Himalaya. Articles should be in English or Tibetan, submitted by email or on CD along with a hard copy and should not exceed 5000 words in length. The views expressed in the Bulletin of Tibetology are those of the contributors alone and not the Namgyal Institute of Tibetology. An article represents the view of the author and does not reflect those of any office or institution with which the author may be associated. -

Seven Papers by Subhuti with Sangharakshita

SEVEN PAPERS by SANGHARAKSHITA and SUBHUTI 2 SEVEN PAPERS May the merit gained In my acting thus Go to the alleviation of the suffering of all beings. My personality throughout my existences, My possessions, And my merit in all three ways, I give up without regard to myself For the benefit of all beings. Just as the earth and other elements Are serviceable in many ways To the infinite number of beings Inhabiting limitless space; So may I become That which maintains all beings Situated throughout space, So long as all have not attained To peace. SEVEN PAPERS 3 SEVEN PAPERS BY SANGHARAKSHITA AND SUBHUTI 2ND EDITION (2.01) with thanks to: Sangharakshita and Subhuti, for the talks and papers Lokabandhu, for compiling this collection lulu.com, the printers An A5 format suitable for iPads is available from Lulu; for a Kindle version please contact Lokabandhu. This is a not-for-profit project, the book being sold at the per-copy printing price. 4 SEVEN PAPERS Contents Introduction 8 What is the Western Buddhist Order? 9 Revering and Relying upon the Dharma 39 Re-Imagining The Buddha 69 Buddhophany 123 Initiation into a New Life: the Ordination Ceremony in Sangharakshita's System oF Spiritual Practice 127 'A supra-personal force or energy working through me': The Triratna Buddhist Community and the Stream of the Dharma 151 The Dharma Revolution and the New Society 205 A Buddhist Manifesto: the Principles oF the Triratna Buddhist Community 233 Index 265 Notes 272 SEVEN PAPERS 5 6 SEVEN PAPERS SEVEN PAPERS 7 Introduction This book presents a collection of seven recent papers by either Sangharakshita or Subhuti, or both working together. -

Compassion and Emptiness in Early Buddhist Meditation Provides a Window Into the Depth and Beauty of the Buddha’S Liberating Teachings

‘This book is the result of rigorous textual scholarship that can be valued not only by the academic community, but also by Buddhist practitioners. This book serves as an important bridge between those who wish to learn about Buddhist thought and practice and those who wish to learn from it.... As a monk engaging himself in Buddhist meditation as well as a professor applying a historical-critical methodology, Bhikkhu Anālayo is well positioned to bridge these two com munities who both seek to deepen their understanding of these texts.’ – from the Foreword, 17th Karmapa Ogyen Trinley Dorje ‘In this study, Venerable Anālayo Bhikkhu brings a meticulous textual analysis of Pali texts, the Chinese Agamas and related material from Sanskrit and Tibetan to the foundational topics of compassion and emptiness. While his analysis is grounded in a scholarly approach, he has written this study as a helpful guide for meditation practice. The topics of compassion and emptiness are often associated with Tibetan Buddhism but here Venerable Anālayo makes clear their importance in the early Pali texts and the original schools.’ – Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo ‘This is an intriguing and delightful book that presents these topics from the viewpoint of the early suttas as well as from other perspectives, and grounds them in both theory and meditative practice.’ – Bhikshuni Thubten Chodron ‘A gift of visionary scholarship and practice. Anālayo holds a lamp to illuminate how the earliest teachings wed the great heart of compassion and the liberating heart of emptiness and invites us to join in this profound training.’ – Jack Kornfield ‘Arising from the author’s long-term, dedicated practice and study, Compassion and Emptiness in Early Buddhist Meditation provides a window into the depth and beauty of the Buddha’s liberating teachings. -

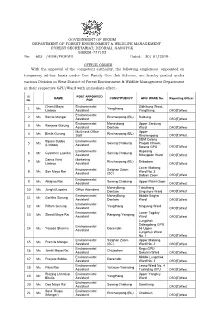

West District of Forest Environment & Wildlife Management Department in Their Respective GPU/Ward with Immediate Effect

GOVERNMENT OF SIKKIM DEPARTMENT OF FOREST ENVIRONMENT & WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT FOREST SECRETARIAT, DEORALI, GANGTOK SIKKIM-737102 No: 605 /ADM/FEWMD Dated: 30/ 01/2019 OFFICE ORDER With the approval of the competent authority, the following employees appointed on temporary ad-hoc basis under One Family One Job Scheme, are hereby posted under various Division in West District of Forest Environment & Wildlife Management Department in their respective GPU/Ward with immediate effect:- Sl. POST APPOINTED NAME CONSTITUENCY GPU/ WARD No. Reporting Officer No. FOR Chemi Maya Environmental Sidhibung Ward, 1 Ms Yangthang Limboo Assistant Yangthang DFO(T)West Environmental 2 Ms Sanita Mangar Rinchenpong (BL) Suldung Assistant DFO(T)West Environmental Maneybong Upper Sardung 3 Ms Ranjana Gurung Assistant Dentam Ward DFO(T)West Multi-task Office Upper Bimla Gurung Rinchenpong (BL) 4 Ms Staff Rinchenpong DFO(T)West SDM Colony Sipora Subba Environmental Soreng Chakung Pragati Chowk, 5 Ms (Limboo) Assistant Soreng GPU DFO(T)West Environmental Rupsang 6 Mr Gyalchen Lepcha Soreng Chakung Assistant Bitteygaon Ward DFO(T)West Dama Yanti Marketing 7 Mr Rinchenpong (BL) Sribadam Limboo Assistant DFO(T)West Lower Mabong Environmental Salghari Zoom San Maya Rai Ward No. 3 8 Ms Assistant (SC) Salbari Zoom DFO(T)West Environmental 9 Ms Alkajina Rai Soreng Chakung Upper Pakki Gaon Assistant DFO(T)West ManeyBong Takuthang Jungkit Lepcha Office Attendant 10 Ms Dentam Singshore Ward DFO(T)West Environmental ManeyBong Middle Begha 11 Mr Gorkha Gurung Assistant Dentam Ward DFO(T)West Environmental 12 Mr Pritam Gurung Yangthang Singyang Ward Assistant DFO(T)West Environmental Lower Togday 13 Ms Shanti Maya Rai Rangang Yangang Assistant Ward DFO(T)West Lungchok Salangdang GPU Environmental Yasoda Sharma Daramdin 58 Upper 14 Ms Assistant Lungchuk Ward No. -

Sangharakshita Seminar Highlights

sangharakshita digital classics: seminar highlights cultivating the heart of patience: lessons from the bodhicaryavatara preface The basis for this text is a seminar, led by Sangharakshita, on the third reunion retreat of the men ordained at Guhyaloka1 in 2005. This week- long retreat took place at Padmaloka2 in June 2008. Sangharakshita chose the topic of study, the sixth chapter of Shantideva's Bodhicaryavatara, on the Perfection of Forbearance (Kshanti). * editor’s note As in any seminar, the conversations transcribed here were often off- the-cuff, with quotations and references made mostly from memory. We’ve tried to make sure that any factual inaccuracies which may have arisen as a result are contextualised and, if possible, corrected. Footnote references for web-linked Wikipedia terms are generally derived from the corresponding Wikipedia entry. For this abridged version of the seminar transcript, we have focussed on Sangharakshita’s direct commentary on the text itself, removing many of the questions and comments of the attendees, along with the conversations that arose from them. We do not identify the speaker of those that remain but simply denote the question or comment with ‘Q’. 1 Guhyaloka (‘The Secret Realm’) is a retreat centre in Spain specializing in men’s long ordination retreats. 2 Padmaloka (‘The Realm of the Lotus’) is a Buddhist retreat centre for men in Norfolk, England. * Attending with Sangharakshita were: Abhayanaga, Amalavajra, Balajit, Dharmamodana, Dhira, Dhiraka, Dhivan, Gambhiradaka, Jayagupta, Jayarava, Jayasiddhi, Jinapalita, Khemajala, Naganataka, Nityabandhu, Priyadaka, Samudraghosha, and Vidyakaya. Transcribed by Amalavajra, Aniccaloka, Norfolk, April 2009. Digital edition edited and prepared by Candradasa. -

Accepted List Candidates for 02 (Two) Vacant Posts of Civil Judge-Cum-Judicial Magistrate (Grade –Iii) in the Cadre of Sikkim Judicial Service

ACCEPTED LIST CANDIDATES FOR 02 (TWO) VACANT POSTS OF CIVIL JUDGE-CUM-JUDICIAL MAGISTRATE (GRADE –III) IN THE CADRE OF SIKKIM JUDICIAL SERVICE Sl. Name & Address of Correspondence Permanent Address, Phone No Numbers & . Email id 1 Abhishek Singh, Ganga Nagar, Siliguri, Darjeeling, C/o Shyam Kishore Singh, Near Ration West Bengal- 734005, Shop, Patiramjote, Matigara, M. No.: 9734177736 Darjeeling, West Bengal- 734010 [email protected] 2 Mr. Aditya Subba, Near Central Bank ATM, Near Central Bank ATM, Mirik Bazar, Darjeeling, Mirik Bazar, Darjeeling, West Bengal- 734214 West Bengal- 734214 M. No.: 8918588575 [email protected] 3 Ms. Aita Hangma Limboo, Tikjeck, Tikjeck, West Sikkim – 737111, West Sikkim - 737111 M. No.: 8670355901 [email protected] 4 Ms. Anu Lohar, Development Area, Development Area, C/0 Santosh Ration Shop, C/0 Santosh Ration Shop, New Puspa Garage, Gangtok- New Puspa Garage, Gangtok- 737101 737101, M. No.: 9560430462, [email protected] 5 Ms. Anusha Rai, Mirik Ward No. 3, Thana line, Mirik, Near Techno India Group Public Darjeeling, School, West Bengal- 734214 New Chamta, Sukna, Siliguri, M. No: 8447603441/7551014923 Darjeeling, West Bengal- 734009 anusharaiii/[email protected] 6 Ms. Aruna Chhetri, Upper Syari, Near Hotel Royal Plaza, Upper Syari, Gangtok, East Sikkim- 737101, Near Hotel Royal Plaza, M. No.: 7872969762 Gangtok, East Sikkim- 737101 [email protected] 7 Mr. Ashit Rai, Gumba Gaon, Sittong-II, Mahishmari, P.O- Champasari, P.O. Bagora, P.S. Kurseong- 734224, P.S. Pradhan Nagar, Dist: Darjelling, West Bengal. C/O- Khem Kr. Rai-734003, M. No.: Dist: Darjeeling, West Bengal. +918670758135/8759551258 [email protected] 8 Mr.