Kesariya Stupa: Recently Excavated Architectural Marvel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2011-2012 West-Champaran, Bihar

Ch F-X ang PD e w w m w Click to buy NOW! o . .c tr e ac ar DISTRICT HEALTH ACTION PLAN ker-softw 2011-2012 DISTRICT HEALTH SOCIETY West-Champaran, Bihar 1 Ch F-X ang PD e w w m PREFACE w o Click to buy NOW! . .c tr e ac ar ker-softw National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) is one of the major health schemes run by Ministry of health and family welfare, GoI. The basic concept of the mission is to enhance the access of Quality health services to the poorest of the poor of the society and improve the health status of the community. It envisages to improve the health status of the rural mass through various programmes. All the health services should be provided to the pregnant women such as ANC checkups, Post Natal Care, IFA tablets for restricting the enemia cases and other reproductive child health releted services. It also focuses on promotion of institutional delivery for restricting the infant and as well as maternal deaths. Immunization is also a very important component which plays a vital role in child and mother health. Family planning and control of other diseases are also other focus areas. The NRHM has a strong realization that it is important to involve community for the improvement of health status of the community through various stake holders such as ASHA, AWWs, PRI, NGOs etc. ASHA is a link worker between the client and the health service providers. The skill of the health functionaries such as ANMs LHVs should be upgraded through proper orientation to ensure quality of care in health services . -

Nomenclature of Post Graduate Courses in Buddhist Studies

UNIVERSITY OF JAMMU CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM FORPOST GRADUATE PROGRAMME IN THE DEPARTMENT OF BUDDHIST STUDIES W.E.F. THE ACADEMIC YEAR 2020-21 Nomenclature of Post Graduate Courses in Buddhist Studies Nomenclature of courses will be done in such a way that the course code will consist of eleven characters. The first character ‘P’ stands for Post Graduate. The second character ‘S’ stands for Semester. Next two characters will denote the Subject Code. Subject Subject Code Buddhist Studies BS Next character will signify the nature of the course. T- Theory Course D- Project based Courses leading to dissertation (e.g. Major, Minor, Mini Project etc.) L- Training S- Independent Study V- Special Topic Lecture Courses Tu- Tutorial The succeeding character will denote whether the course is compulsory “C” or Elective “E”. The next character will denote the Semester Number. For example: 1 will denote Semester— I, and 2 will denote Semester— II Last two characters will denote the paper Number. Nomenclature of P G Courses PSBSTC101 P POST GRADUATE S SEMESTER BS BUDDHIST STUDIES (SUBJECT CODE) T THEORY (NATURE OF COURSE) C COMPULSORY 1 SEMESTER NUMBER 01 PAPER NUMBER O OPEN 1 Semester wise Distribution of Courses and Credits SEMESTER- I (December 2018, 2019, 2020 & 2021) Course code Paper Credits PSBSTC101 History of Buddhism in India 6 PSBSTC102 Fundamentals of Buddhist Philosophy 6 PSBSTC103 Pali Language and History 6 PSBSTC104 Selected Pali Sutta Texts 6 SEMESTER- II (May 2019, 2020 and 2021) Course code Paper Credits PSBSTC201 Vinaya -

Glimpses of Sugarcane Varietal Screening and Improvement at Pusa, Bihar

ACTA SCIENTIFIC AGRICULTURE (ISSN: 2581-365X) Volume 4 Issue 3 March 2020 Review Article Glimpses of Sugarcane Varietal Screening and Improvement at Pusa, Bihar Balwant Kumar* Received: January 18, 2020 SRI, DRPCAU, Pusa, Bihar, India Published: February 08, 2020 Balwant Kumar, SRI, DRPCAU, Pusa, Bihar, India. *Corresponding Author: © All rights are reserved by Balwant DOI: 10.31080/ASAG.2020.04.0793 Kumar. Abstract Sugarcane is primarily grown in nine states of India namely; Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Gujarat, Haryana, Karnataka, Punjab, and Tamil Nadu. During early 19th century sugarcane cultivation started as cash crop and number of sugar facto- ries open keeping in view a glimpses of sugarcane varietal screening and Improvement has been reviewed and found that Bihar was rich in term of sugar factories and its 20-40% share in national sugar production was already reported. It was the introduction of Co seedling that replace local varieties under cultivation those were Co 210, Co213, Co 214, Co 313, Co 331, Co 513,Co 356, Co 395,Co 453,Co508 and CoK 32, Co 383, Co 622,Co 419,Co 617,Co1148 and Co 1158 while in present varietal scenario cultivated varieties are Co 0238, Co 0118, Co 98014, CoP 9301, CoLk 94184, CoP 112, CoSe 01434, CoP 09437, BO 154 and CoP 16437. It was also found that POJ 2878, Co285, Co281, CP 28/11, Co213 & Co205 were mainly responsible for improvement in high yield and high sugar. The varietal development and evaluation of sugarcane varieties started in Bihar by after that Central Sugarcane Research Institute was established 1932 since then total 281 clones were developed at SRI, while several Sugarcane varieties of other place were also evalu- ated. -

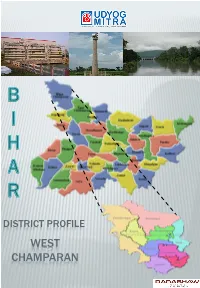

West Champaran Introduction

DISTRICT PROFILE WEST CHAMPARAN INTRODUCTION West Champaran is an administrative district in the state of Bihar. West Champaran district was carved out of old champaran district in the year 1972. It is part of Tirhut division. West Champaran is surrounded by hilly region of Nepal in the North, Gopalganj & part of East Champaran district in the south, in the east it is surrounded by East Champaran and in the west Padrauna & Deoria districts of Uttar Pradesh. The mother-tongue of this region is Bhojpuri. The district has its border with Nepal, it has an international importance. The international border is open at five blocks of the district, namely, Bagha- II, Ramnagar, Gaunaha, Mainatand & Sikta, extending from north- west corner to south–east covering a distance of 35 kms . HISTORICAL BACKGROUND The history of the district during the late medieval period and the British period is linked with the history of Bettiah Raj. The British Raj palace occupies a large area in the centre of the town. In 1910 at the request of Maharani, the palace was built after the plan of Graham's palace in Calcutta. The Court Of Wards is at present holding the property of Bettiah Raj. The rise of nationalism in Bettiah in early 20th century is intimately connected with indigo plantation. Raj Kumar Shukla, an ordinary raiyat and indigo cultivator of Champaran met Gandhiji and explained the plight of the cultivators and the atrocities of the planters on the raiyats. Gandhijii came to Champaran in 1917 and listened to the problems of the cultivators and the started the movement known as Champaran Satyagraha movement to end the oppression of the British indigo planters. -

The Nibbāna of Mahākassapa the Elder: Notes on a Buddhist Narrative Transmitted in Thai and Lao Literature François Lagirarde

The Nibbāna of Mahākassapa the Elder: Notes on a Buddhist Narrative Transmitted in Thai and Lao Literature François Lagirarde To cite this version: François Lagirarde. The Nibbāna of Mahākassapa the Elder: Notes on a Buddhist Narrative Transmit- ted in Thai and Lao Literature. Buddhist Legacies in Mainland Southeast Asia, 2006. hal-01955848 HAL Id: hal-01955848 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01955848 Submitted on 21 Dec 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. François Lagirarde The Nibbāna of Mahākassapa the Elder: Notes on a Buddhist Narrative Transmitted in Thai and Lao Literature THIS LEGEND OF MAHākassapa’S NIBBāNA from his last morning, to his failed farewell to King Ajātasattu, to his parinibbāna in the evening, to his ultimate “meeting” with Metteyya thousands of years later—is well known in Thailand and Laos although it was not included in the Pāli tipiṭaka or even mentioned in the commentaries or sub-commentaries. In fact, the texts known as Mahākassapatheranibbāna (the Nibbāna of Mahākassapa the Elder) represent only one among many other Nibbāna stories known in Thai-Lao Buddhist literature. In this paper I will attempt to show that the textual tradition dealing with the last moments of many disciples or “Hearers” of the Buddha—with Mahākassapa as the first one—became a rich, vast, and well preserved genre at least in the Thai world. -

Download Download

Transcultural Studies 2016.1 121 Local Agency in Global Movements: Negotiating Forms of Buddhist Cosmopolitanism in the Young Men’s Buddhist Associations of Darjeeling and Kalimpong Kalzang Dorjee Bhutia, Grinnell College Introduction Darjeeling and Kalimpong have long played important roles in the development of global knowledge about Tibetan and Himalayan religions.1 While both trade centres became known throughout the British empire for their recreational opportunities, favourable climate, and their famous respective exports of Darjeeling tea and Kalimpong wool, they were both the centres of a rich, dynamic, and as time went on, increasingly hybrid cultural life. Positioned as they were on the frontier between the multiple states of India, Bhutan, Sikkim, Tibet, and Nepal, as well as the British and Chinese empires, Darjeeling and Kalimpong were also both home to multiple religious traditions. From the mid-nineteenth century onwards, Christian missionaries from Britain developed churches and educational institutions there in an attempt to gain a foothold in the hills. Their task was not an easy one, due to the strength of local traditions and the political and economic dominance of local Tibetan-derived Buddhist monastic institutions, which functioned as satellite institutions and commodity brokers for the nearby Buddhist states of Tibet, Sikkim, and Bhutan. British colonial administrators and scholars from around the world took advantage of the easy proximity of these urban centres for their explorations, and considered them as museums of living Buddhism. While Tibet remained closed for all but a lucky few, other explorers, Orientalist 1 I would like to thank the many people who contributed to this article, especially Pak Tséring’s family and members of past and present YMBA communities and their families in Darjeeling, Kalimpong, and Sikkim; L. -

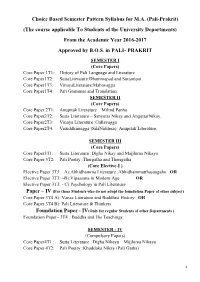

Pali-Prakrit) (The Course Applicable to Students of the University Departments) from the Academic Year 2016-2017 Approved by B.O.S

Choice Based Semester Pattern Syllabus for M.A. (Pali-Prakrit) (The course applicable To Students of the University Departments) From the Academic Year 2016-2017 Approved by B.O.S. in PALI- PRAKRIT SEMESTER I (Core Papers) Core Paper 1T1: History of Pali Language and Literature Core Paper1T2: SuttaLiterature:Dhammapad and Suttanipat Core Paper1T3: VinayaLiterature:Mahavagga. Core Paper1T4: Pali Grammar and Translation SEMESTER II (Core Papers) Core Paper 2T1: Anupitak Literature – Milind Panho Core Paper2T2: Sutta Literature – Sanyutta Nikay and AnguttarNikay. Core Paper2T3: Vinaya Literature :Cullavagga Core Paper2T4: Visuddhimagga (SilaNiddesa): Anupitak Literature. SEMESTER III (Core Papers) Core Paper3T1: Sutta Literature :Digha Nikay and Majjhima Nikaya Core Paper 3T2: Pali Poetry :Thergatha and Therigatha. (Core Elective-I ) Elective Paper 3T3: –A):Abhidhamma Literature :Abhidhammatthasangaho OR Elective Paper 3T3: –B):Vipassana in Modern Age OR Elective Paper 3T3: - C) Psychology in Pali Literature Paper – IV (For those Students who do not adopt the foundation Paper of other subject) Core Paper 3T4 A): Vansa Literature and Buddhist History OR Core Paper 3T4 B): Pali Literature & Thinkers Foundation Paper - IV(Only for regular Students of other Departments ) Foundation Paper– 3T4 : Buddha and His Teachings SEMESTER - IV (Compulsory Papers) Core Paper4T1 : Sutta Literature : Digha Nikaya – Mijjhima Nikaya Core Paper 4T2: Pali Poetry :Khuddaka Nikay (Pali Gatha) 1 (Core Elective-II ) Elective Paper 4T3: –A) Vinaypitaka – Patimokkha OR Elective Paper 4T3: –B) Modern Pali Literature OR Elective Paper 4T3: - C) Atthakatha Literature Paper – IV (For those Students who do not adopt the foundation Paper of other subject) Core Paper 4T4: -A): Comparative Linguistics and Essay OR Core Paper 4T4: -B): Propagation of Pali Literature Foundation Paper - IV(Only for regular Students of other Departments ) Foundation Paper - 4T4: - Pali Language and Literature University of Rashtrasant Tukadoji Maharaj Nagpur M.A. -

Soil Resource of East Champaran (Motihari) District, Bihar Abstract

Soil Resource of East Champaran (Motihari) District, Bihar Abstract 1. Surveyed Area : East Champaran district, Bihar 2. Location : Latitude 26°15´ 16 ´´to 27° 01´ 13´´ N Longitude 84°29´ 13´´ to 85° 17´ 55´´ E 3. Agroclimatic : Middle Gangetic Plain Region (Zone – IV as per planning commission) 4. Total Area of the : 396803 ha District 5. Kind of Survey : Soil Resource Mapping using Remote Sensing and GIS Techniques 6. Base Map : IRS-ID Geocoded Satellite Imagery (1:50,000 scale) Survey of India Topographical maps on 1:50,000 scale. 7. Scale of Mapping : 1:50,000 8. Period of Survey : January, 2015 9. Soil Series Association mapped and their respective area: Sl. No. Mapping Unit Soil Series Association Area(ha) Area% 01 ALb1a1 Kesaria, Rariaha 29773 7.50 02 ALb1a2 Bhawanipur, Partapur, Jhitkahia 70624 17.80 03 ALb1a3 Champapur, Jhajhara, Karmoulia 40742 10.27 04 ALb1a4 Bhakhari, Mathia Mohan 82363 20.75 05 ALb2a1 Mathbanbari, Jhakra 83043 20.93 06 ALb2a2 Sakrar, Parsaunikapur, Fatuha 29482 7.43 07 ALb2b1 Dhekha, Fatuha 2073 0.52 08 ALe2a1 Dumariya Ghat, Madhubani Ghat 10277 2.59 09 ALe2d1 Dumariya Ghat 7279 1.83 10 ALg3a1 Piprakothi, Jitwara 6968 1.76 11 ALn2a1 Tharghatma, Jitwara 9828 2.48 12 Miscellaneous Habitation 4035 1.02 River & Waterbody 20316 5.12 Grand Total 396803 100 i 10. Salient Features: Physiographic division of the soils of the East Champaran district of Bihar: Landscape Physiography Area (ha) Area(%) Alluvium Alluvial Plain 338100 85.20 Flood Plain 9828 2.48 Levee 17556 4.42 Stream/River Banks 6968 1.76 Miscellaneous Habitation 4035 1.02 River & Waterbody 20316 5.12 Total 396803 100 Soils of the district fall in two slope classes: Sl. -

Purbi Champaran (Motihari)

DISTRICT HEALTH ACTION PLAN 2012-13 EAST CHAMPARAN BIHAR Kesaria Budha Stup Mr. Rana P.K. Solanki Dr. Kameshwar Mandal Mr. Abhijeet Sinha (IAS) District Prog.Manager C.S. Cum Member Secretaty D.M. Cum Chairman DHS-East Champaran DHS-East Champaran DHS-East Champaran DISTRICT HEALTH ACTION PLAN EAST CHAMPARAN Developed & Designed by – Mr. Rana P.K. Solanki District Programme Manager DHS, East Champaran Mr. Awadhesh Kumar District Data Assistant (ASHA) DHS , East Champaran Mr. Avinash Dutta Representative, Internal Auditor, DHS East Champaran DISTRICT HEALTH ACTION PLAN 2012-13, DHS. EAST CHAMPARAN (BIHAR) Page 2 of 238 Foreword Recognizing the importance of Health in the process of economic and social development and improving the quality of life of our citizens, the Government of India has resolved to launch the National Rural Health Mission to carry out necessary architectural correction in the basic health care delivery system. This District Health Action Plan (DHAP) is one of the key instruments to achieve NRHM goals. This plan is based on health needs of the district. After a thorough situational analysis of district health scenario this document has been prepared. In the plan, it is addressing health care needs of rural poor especially women and children, the teams have analyzed the coverage of poor women and children with preventive and primitives interventions, barriers in access to health care and spread of human resources catering health needs in the district. The focus has also been given on current availability of health care infrastructure in pubic/NGO/private sector, availability of wide rage of providers. -

In Buddhist Studies

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar University of Social Sciences Dr. Ambedkar Nagar (Mhow), Indore (M.P.) M.A. (MASTER OF ARTS) IN BUDDHIST STUDIES SYLLABUS 2018 Course started from session: 2018-19 M.A. in Buddhist Studies, Session: 2018-19, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar University of Social Sciences, Mhow Page 1 of 19 ikB~;Øe ifjp; (Introduction of the Course) ,e-,- ¼ckS) v/;;u½ ,e-,- (ckS) v/;;u) ikB~;Øe iw.kZdkfyd f}o"khZ; ikB~;Øe gSA ;g ikB~;Øe pkj l=k)ksZa (Semesters) rFkk nks o"kksZ ds Øe esa foHkDr gSA ÁFke o"kZ esa l=k)Z I o II rFkk f}rh; o"kZ esa l=k)Z III o IV dk v/;kiu fd;k tk;sxkA ikB~;dze ds vUrxZr O;k[;kuksa] laxksf"B;ksa] izk;ksfxd&dk;ksZ] V;wVksfj;Yl rFkk iznÙk&dk;ksZ (Assignments) vkfn ds ek/;e ls v/;kiu fd;k tk;sxkA izR;sd l=k)Z esa ckS) v/;;u fo"k; ds pkj&pkj iz'u&i= gksaxsA izR;sd iz'u&i= ds fy, ik¡p bdkb;k¡ (Units) rFkk 3 ØsfMV~l fu/kkZfjr gksaxsA vad&foHkktu ¼izfr iz'u&i=½ 1- lS)kfUrd&iz'u & 60 (Theoretical Questions) 2- vkUrfjd& ewY;kadu & 40 (Internal Assessment) e/;&l=k)Z ewY;kadu + x`g dk;Z + d{kk esa laxks"Bh i= izLrqfr ¼20 + 10+ 10½ ;ksx % & 100 ijh{kk ek/;e % ckS) v/;;u fo"k; fgUnh ,oa vaxzsth nksuksa ek/;e esa lapkfyr fd;k tk,xk A lS)kfUrd iz'u&i= dk Lo#i (Pattern of Theatrical Question paper) nh?kksZŸkjh; iz'u 4 x 10 & 20 vad y?kqŸkjh; iz'u 6 x 5 & 30 vad fVIi.kh ys[ku 2 x 5 & 10 vad ;ksx & 60 M.A. -

West Champaran District, Bihar State

भूजल सूचना पुस्तिका पस्चचमी च륍पारण स्जला, बिहार Ground Water Information Booklet West Champaran District, Bihar State ADMINISTRATIVE MAP WEST CHAMPARAN DISTRICT, BIHAR N 0 5 10 15 20 Km Scale Masan R GAONAHA SIDHAW RAMNAGAR PIPRASI MAINATAND BAGAHA NARKATIAGANJ LAURIYA MADHUBANI SIKTA BHITAHA CHANPATTIA GandakJOGAPATTI R MANJHAULIA District Boundary BETTIAH Block Boundary THAKRAHA BAIRIA Road Railway NAUTAN River Block Headquarter के न्द्रीय भमू मजल िो셍 ड Central Ground water Board Ministry of Water Resources जल संसाधन मंत्रालय (Govt. of India) (भारि सरकार) Mid-Eastern Region Patna मध्य-पर्वू ी क्षेत्र पटना मसिंिर 2013 September 2013 1 Prepared By - Dr. Rakesh Singh, Scientist – ‘B’ 2 WEST CHAMPARAN, BIHAR S. No CONTENTS PAGE NO. 1.0 Introduction 6 - 10 1.1 Administrative details 1.2 Basin/sub-basin, Drainage 1.3 Irrigation Practices 1.4 Studies/Activities by CGWB 2.0 Climate and Rainfall 11 3.0 Geomorphology and Soils 11 - 12 4.0 Ground Water Scenario 12 – 19 4.1 Hydrogeology 4.2 Ground Water Resources 4.3 Ground Water Quality 4.4 Status of Ground Water Development 5.0 Ground Water Management Strategy 19 – 20 5.1 Ground Water Development 5.2 Water Conservation and Artificial Recharge 6.0 Ground Water related issue and problems 20 7.0 Mass Awareness and Training Activity 20 8.0 Area Notified by CGWB/SGWA 20 9.0 Recommendations 20 FIGURES 1.0 Index map of West Champaran district 2.0 Month wise rainfall plot for the district 3.0 Hydrogeological map of West Champaran district 4.0 Aquifer disposition in West Champaran 5.0 Depth to Water Level map (May 2011) 6.0 Depth to Water Level map (November 2011) 7.0 Block wise Dynamic Ground Water (GW) Resource of West Champaran district TABLES 1.0 Boundary details of West Champaran district 2.0 List of Blocks in West Champaran district 3.0 Land use pattern in West Champaran district 4.0 HNS locations of West Champaran 5.0 Blockwise Dynamic Ground Water Resource of West Champaran District (2008-09) 6.0 Exploration data of West Champaran 7.0 Chemical parameters of ground water in West Champaran 3 WEST CHAMPARAN - AT A GLANCE 1. -

Seven Papers by Subhuti with Sangharakshita

SEVEN PAPERS by SANGHARAKSHITA and SUBHUTI 2 SEVEN PAPERS May the merit gained In my acting thus Go to the alleviation of the suffering of all beings. My personality throughout my existences, My possessions, And my merit in all three ways, I give up without regard to myself For the benefit of all beings. Just as the earth and other elements Are serviceable in many ways To the infinite number of beings Inhabiting limitless space; So may I become That which maintains all beings Situated throughout space, So long as all have not attained To peace. SEVEN PAPERS 3 SEVEN PAPERS BY SANGHARAKSHITA AND SUBHUTI 2ND EDITION (2.01) with thanks to: Sangharakshita and Subhuti, for the talks and papers Lokabandhu, for compiling this collection lulu.com, the printers An A5 format suitable for iPads is available from Lulu; for a Kindle version please contact Lokabandhu. This is a not-for-profit project, the book being sold at the per-copy printing price. 4 SEVEN PAPERS Contents Introduction 8 What is the Western Buddhist Order? 9 Revering and Relying upon the Dharma 39 Re-Imagining The Buddha 69 Buddhophany 123 Initiation into a New Life: the Ordination Ceremony in Sangharakshita's System oF Spiritual Practice 127 'A supra-personal force or energy working through me': The Triratna Buddhist Community and the Stream of the Dharma 151 The Dharma Revolution and the New Society 205 A Buddhist Manifesto: the Principles oF the Triratna Buddhist Community 233 Index 265 Notes 272 SEVEN PAPERS 5 6 SEVEN PAPERS SEVEN PAPERS 7 Introduction This book presents a collection of seven recent papers by either Sangharakshita or Subhuti, or both working together.