Studentified Areas As Contested Heterotopias : Findings from Southampton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

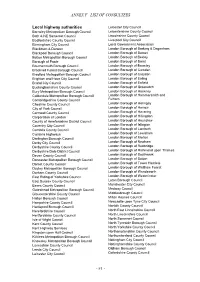

Annex F –List of Consultees

ANNEX F –LIST OF CONSULTEES Local highway authorities Leicester City Council Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council Leicestershire County Council Bath & NE Somerset Council Lincolnshire County Council Bedfordshire County Council Liverpool City Council Birmingham City Council Local Government Association Blackburn & Darwen London Borough of Barking & Dagenham Blackpool Borough Council London Borough of Barnet Bolton Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Bexley Borough of Poole London Borough of Brent Bournemouth Borough Council London Borough of Bromley Bracknell Forest Borough Council London Borough of Camden Bradford Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Croydon Brighton and Hove City Council London Borough of Ealing Bristol City Council London Borough of Enfield Buckinghamshire County Council London Borough of Greenwich Bury Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Hackney Calderdale Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Hammersmith and Cambridgeshire County Council Fulham Cheshire County Council London Borough of Haringey City of York Council London Borough of Harrow Cornwall County Council London Borough of Havering Corporation of London London Borough of Hillingdon County of Herefordshire District Council London Borough of Hounslow Coventry City Council London Borough of Islington Cumbria County Council London Borough of Lambeth Cumbria Highways London Borough of Lewisham Darlington Borough Council London Borough of Merton Derby City Council London Borough of Newham Derbyshire County Council London -

A Fairer Southampton

A Fairer Southampton A Fairer Southampton Southampton Fairness Commission Final Report: December 2015 1 A Fairer Southampton Contents 1. Acknowledgements 2. Foreword from the Chair 3. Our vision and principles 4. Executive summary and recommendations 5. The Southampton Fairness Commission 6. Why fairness is important for everyone 7. The Southampton picture – not such a fair deal for everyone 8. Consultation, participation and engagement 9. The Commission’s recommendations: Fairer employment Fairer living Fairer organisations Fairer communities 10. A fairness index for the city 11. Next steps Appendix 1: Speakers and facilitators 2 A Fairer Southampton 1. Acknowledgements The Southampton Fairness Commission would like to thank: The countless individuals, groups, organisations who invested their time and energy in contributing to the Commission’s work – there are too many to name individually Those who shared their knowledge and expertise Those who gave us their personal testimonials and life experiences Those who shared their enthusiasm , innovation and ideas Speakers who gave formal presentations at the themed meetings. Other Fairness Commissions that have inspired us. We would also like to thank people who spoke and gave their support at the initial launch of the Southampton Fairness Commission - Lela Kogbara (Islington Council) John Denham (MP for Southampton Itchen until May 2015) and Paula Claisse from KPMG. We would particularly like to thank Councillor Andy Hull (Islington Council) for sharing learning and experience of the first ever Fairness Commission with us. Find out more about the Southampton Fairness Commission by visiting our website: www.southamptonfairnesscommission.org 3 A Fairer Southampton 2. Foreword from the Chair Like everyone else, I want a good life for myself, my family, and my friends. -

Choosing a Nursery/ School/College

SENDIASS Training for Parents & Carers of children with Special Educational Needs (0-25) Welcome Choosing a nursery/ school/ college for your child with SEN ( Special Educational Needs) Your Trainers: Hannah Pinchin and Hayley Legg HOUSE KEEPING • Microphones on mute please • Feel free to add comments and questions to the chat box and we will email you a summary sheet with the answers on after the talk • PowerPoint will be shared after the training – sit back and relax! SENDIASS (Special Educational Needs and Disability Information Advice and Support Service) Who are we? SEND Information Advice Support A service for those Providing factual Providing impartial Providing living or working information found in advice on what confidential with ages 0-25yrs SEND Law and steps to take in the individualised with Special practices as well as areas of Education, support to empower Educational Needs local knowledge and Health and Social those who seek our and Disabilities signposting Care assistance TYPES OF EDUCATION MAINTAINED INDEPENDENT Educational institutions Educational institutions controlled and funded independent of local (maintained) by local authorities / secretary of authorities state MAINSTREAM SPECIALIST RESOURCE BASE A mainstream school is a A special school is a school Resource bases provide school which is not a which is “specially targeted specialist support special school and is either organised to make special but are not separate a maintained school or an educational provision for schools or institutions. Academy (section 83 CAFA pupils with SEN” (section They are units within a 2014). 337 of the Education Act mainstream school. 1996). How to make a short list List your ideal school (involve the child/YP if possible) 1. -

Q2 1617 LA Referrals

Referrals to Local Authority Adoption Agencies from First4Adoption by region Q2 July-September 2016 Yorkshire & The Humber LA Adoption Agencies North East LA Adoption Agencies Durham County Council 13 North Yorkshire County Council* 30 1 Northumberland County Council 8 Barnsley Adoption Fostering Unit 11 South Tyneside Council 8 Rotherham Metropolitan Borough Council 11 2 North Tyneside Council 5 Bradford Metropolitan Borough Council 10 Redcar Cleveland Borough Council 5 Hull City Council 10 1 Web Referrals Phone Referrals Middlesbrough Council 3 East Riding Of Yorkshire Council 9 City Of Sunderland 2 Cumbria County Council 7 Gateshead Council 2 Calderdale Metropolitan Borough Council 6 1 Newcastle Upon Tyne City Council 2 0 3.5 7 10.5 14 Leeds City Council 6 1 Web Referrals Phone Referrals Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council 5 Hartlepool Borough Council 4 North Lincolnshire Adoption Service 4 1 City Of York Council 3 North East Lincolnshire Adoption Service 3 1 Darlington Borough Council 2 Kirklees Metropolitan Council 2 1 Sheffield Metropolitan City Council 2 Wakefield Metropolitan District Council 2 * Denotes agencies with more than one office entry on the agency finder 0 10 20 30 40 North West LA Adoption Agencies Liverpool City Council 30 Cheshire West And Chester County Council 16 Bolton Metropolitan Borough Council 11 1 Manchester City Council 9 WWISH 9 Lancashire County Council 8 Oldham Council 8 1 Sefton Metropolitan Borough Council 8 2 Web Referrals Phone Referrals Wirral Adoption Team 8 Salford City Council 7 3 Bury Metropolitan -

Appendix a , Item 154. PDF 270 KB

Combined Fire Authority Consultation Findings Report Part one – key findings summary November 2018 0 Contents – Part One Project overview ....................................................................................................... 2 Executive summary of key findings ........................................................................ 3 Demographic profile of respondents ...................................................................... 4 Key findings summary ............................................................................................. 6 Further detail on the consultation findings can be viewed in Part Two of this report. Imagery has been used throughout the report to illustrate findings; all icons are made by Freepik, available from www.flaticon.com. 1 Project overview Having worked successfully in partnership for three years, Hampshire Fire and Rescue Authority (HFRA), which is responsible for Hampshire Fire and Rescue Service (HFRS), and Isle of Wight Council (IWC), which is responsible for the Isle of Wight Fire and Rescue Service (IWFRS), agreed to consult on whether or not to submit a proposal to central Government for the creation of a new Combined Fire Authority, which would cover Hampshire, Isle of Wight, Portsmouth and Southampton. Residents’ and stakeholders’ views were sought via an ‘open’ consultation, held from midday on Monday 6 August until midnight on Friday 26 October 2018. Responses could be submitted through an online Response Form, by paper version or as ‘unstructured’ letters and -

The Provision of a Coroners Service to Southampton City Council.Pdf

DECISION-MAKER: EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR- COMMUNITIES, CULTURE AND HOMES SUBJECT: THE PROVISION OF A CORONERS SERVICE TO SCC AND A FUNDING AGREEMENT BETWEEN HCC AND SCC FOR THAT SERVICE. DATE OF DECISION: May 6, 2020 REPORT OF: HEAD OF SERVICE - CONSUMER PROTECTION AND ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES CONTACT DETAILS AUTHOR: Name: Rosie Zambra Tel: 023 8083400 E-mail: [email protected] Director Name: Mary D’Arcy Tel: 023 80 E-mail: mary.d’[email protected] STATEMENT OF CONFIDENTIALITY Not applicable BRIEF SUMMARY A decision needs to be made in relation to Southampton City Council entering into a formal funding agreement with Hampshire Country Council to provide a Coroners Service. This is a statutory function that we must have and at the present time a formal agreement and funding arrangements is not in place. Given the current COVID-19 emergency it is proposed that the decision to enter into this agreement is urgent and therefore that this decision is taken by the Executive Director for Communities, Culture and Homes. RECOMMENDATIONS: This report is submitted for consideration as a general exception under paragraph 15 of the Access to Information procedure Rules in Part 4 of the Council’s Constitution, notice having been given to the Chair of Overview and Scrutiny Management Committee and the public. (i) To approve expenditure of £560,000 as set out in paragraph 7 of this report and to enter into the funding agreement between Southampton City Council and Hampshire Council for the Provision of a Coroners Service for 2020/21. REASONS FOR REPORT RECOMMENDATIONS 1. It is a statutory requirement for the Southampton City Council to have a Coroners Service. -

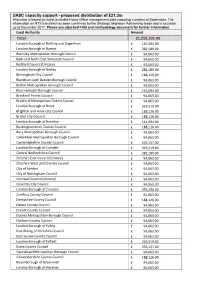

UASC Capacity Support - Proposed Distribution of £21.3M Allocation Is Based on Latest Available Home Office Management Data Capturing Numbers at September

UASC capacity support - proposed distribution of £21.3m Allocation is based on latest available Home Office management data capturing numbers at September. The information on NTS transfers has been confirmed by the Strategic Migration Partnership leads and is accurate up to December 2017. Please see attached FAQ and methodology document for further information. Local Authority Amount Total 21,258,203.00 London Borough of Barking and Dagenham £ 141,094.00 London Borough of Barnet £ 282,189.00 Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council £ 94,063.00 Bath and North East Somerset Council £ 94,063.00 Bedford Council (Unitary) £ 94,063.00 London Borough of Bexley £ 282,189.00 Birmingham City Council £ 188,126.00 Blackburn with Darwen Borough Council £ 94,063.00 Bolton Metropolitan Borough Council £ 94,063.00 Bournemouth Borough Council £ 141,094.00 Bracknell Forest Council £ 94,063.00 Bradford Metropolitan District Council £ 94,063.00 London Borough of Brent £ 329,219.00 Brighton and Hove City Council £ 188,126.00 Bristol City Council £ 188,126.00 London Borough of Bromley £ 141,094.00 Buckinghamshire County Council £ 188,126.00 Bury Metropolitan Borough Council £ 94,063.00 Calderdale Metropolitan Borough Council £ 94,063.00 Cambridgeshire County Council £ 235,157.00 London Borough of Camden £ 329,219.00 Central Bedfordshire Council £ 282,189.00 Cheshire East Council (Unitary) £ 94,063.00 Cheshire West and Chester Council £ 94,063.00 City of London £ 94,063.00 City of Nottingham Council £ 94,063.00 Cornwall Council (Unitary) £ 94,063.00 Coventry City -

Tender for the Provision of Independent Fostering Agency Services

TENDER FOR THE PROVISION OF INDEPENDENT FOSTERING AGENCY SERVICES SOUTHAMPTON CITY COUNCIL (“The Council”) invites expressions of interest from suitably experienced firms/organisations for the provision of Independent Fostering Agency services. Southampton City Council are procuring these services for themselves and also for and on behalf of Bracknell Forest Council, Hampshire County Council, Oxfordshire County Council, Portsmouth City Council, Reading Borough Council, Slough Borough Council, Surrey County Council, West Berkshire Council, Windsor and Maidenhead Council and Wokingham Borough Council. The services will be provided through an Approved Provider List, Framework contract and Block contracts. The Approved Provider List will consist of all those providers that meet the council’s pre-determined criteria and accept the council’s contract conditions. Providers will be listed against a Lot or any combination of Lots from those listed below. The Framework Arrangement will contain multiple providers, divided into Lots. Placements through the Framework Arrangement will be made through a call-off process as set out in the framework agreement. Block contracts may also contain multiple providers, divided into Lots. Providers who wish to tender for the Framework and/or Block contracts will only be selected from those that have met the criteria for placement on the Approved Provider List and additional requirements detailed in the Instructions to Applicants. Providers will enter into an agreement for placement onto the Approved Provider List. Providers who are selected for inclusion on the Framework contract will enter into an agreement with the lead council (Southampton City Council), those Providers who are selected to provide services under a Block arrangement will enter into a services contract with those Councils (referred to above) which wish to have block arrangements. -

Southampton and Portsmouth City Deal

Southampton and Portsmouth City Deal Executive Summary The Southampton and Portsmouth City Deal will maximise the economic strengths of these two coastal cities and the wider Solent area, by supporting further growth in the area‟s maritime, marine and advanced manufacturing sectors. Across Southampton, Portsmouth and the Solent, the marine and maritime sector already accounts for over 20% of gross value added and provides 40,000 jobs locally. Over the next 12 years this sector is expected to grow by 5%, driven in part by key assets such as the Port of Southampton, Portsmouth Naval Base; and the Solent Marine Cluster – which includes Lloyds Register and the Southampton Marine and Maritime Institute. Advanced manufacturing is also an area of strength, growing during the recent recession and creating almost 5,000 new jobs. The flagship proposal for this City Deal will support further growth in these sectors by unlocking two high- profile sites within Southampton and Portsmouth – one of which involves Ministry of Defence owned land. These sites, once developed, will provide: new employment space; new housing; and lever in significant amounts of new private sector investment into the economy. To complement this, the City Deal will also implement programmes to: align skills provision to employer needs; tackle long term unemployment and youth unemployment; and enable small and medium enterprises to grow through the provision of effective business support. Over its lifetime the Solent Local Enterprise Partnership predict the City Deal will deliver: Over 4,700 permanent new jobs particularly focussed in marine, maritime and advanced manufacturing sectors. Over 13,000 construction jobs. -

APPENDIX 2 Solent Combined Authority Governance Review

APPENDIX 2 Solent Combined Authority Governance Review. List of stakeholder contacted by Isle of Wight Council • IWALC • Federation of small businesses • Visit Isle of Wight • Bembridge Parish Council • Chale Parish Council • Shanklin Town Council • Southern Vectis • CLA • Isle of Wight NHS Trust • Isle of Wight Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) • Police, Isle of Wight District • Isle of Wight Chamber of Commerce • Isle Help Advice Hub • Isle of Wight Citizens Advice Bureau • Age UK Isle of Wight • Island Roads • Amey • Spectrum Housing • Vectis Housing • Red Funnel • Wightlink • Hovertravel • IW College List of stakeholders contacted by Southampton City Council. • Allied Developments • Associated British Ports • Aster Group • Basingstoke and Deane Borough Council (on behalf of the three unitary authorities) • Business South • City College Southampton • East Hampshire District Council (on behalf of the three unitary authorities) • Eastleigh Borough Council (on behalf of the three unitary authorities) • EM3 LEP Chair (on behalf of the three unitary authorities) • Fareham Borough Council (on behalf of the three unitary authorities) • Federation of Small Businesses • First Bus Hampshire and Dorset • Fleet Town Council (on behalf of the three unitary authorities) • Go South Coast • Gosport Borough Council (on behalf of the three unitary authorities) • Great Western Railway B - 63 • Hammerson • Hampshire & Isle of Wight Community Rehabilitation Company • Hampshire and Regional Property Group • Hampshire Chamber of Commerce (on behalf of the -

Local Sustainable Transport Fund - Application Form

Local Sustainable Transport Fund - Application Form Guidance on the Application Process is available at: www.dft.gov.uk/pgr/regional/ Bids for both small projects and initial proposals for large projects should be no more than 20 pages long. Applicant Information Local transport authority name(s)*: Isle of Wight Council Senior Responsible Owner name and position: Mr Peter Hayward, Strategic Manager, Highways and Transport Bid Manager name and position: Mrs Rachel Mills, Integrated Transport Manager Contact telephone number: 01983 821000 ext 8792 Email address: [email protected] Postal address: Highways and Transport Economy and Environment County Hall High Street Newport Isle of Wight PO30 1UD Website address for published bid: http://www.iwight.com/living_here/environment/Transport_Strategies/LSTF/default.asp - 1 - SECTION A - Project description and funding profile A1. Project name: Sustainable transport access to tourism A2. Headline description This bid seeks to upgrade, improve and promote our sustainable transport network in order to grow our green tourism market and establish the Island as a leading green tourism destination; including: Integrated transport hubs – establishment of strategic hubs providing live transport/tourism information and interchange facilities. Public transport information and support – delivery of a public transport RTI system providing live bus/train/ferry information accessible at hubs, rail stations, ferry terminals, via the web and phone app. New and enhanced tourism related bus services. Walking and cycling – increasing access and improvements to our network. Marketing, promotion and ‘hearts and minds’ – initiatives to improve and promote our green tourism offer. A3. Geographical area: Isle of Wight A4. Type of bid (please tick relevant box): Small project bids Tranche 2 bid A5. -

“Staying Put” Protocol

South Central Independent Fostering Agency (IFA) Contract: “Staying Put” Protocol For use with placements made by the following Local Authorities: Bracknell Forest Council, Hampshire County Council, Oxfordshire County Council, Portsmouth City Council, Reading Borough Council, Royal Borough Windsor & Maidenhead, Slough Borough Council, Southampton City Council, Surrey Council, West Berkshire Council, and Wokingham Borough Council. This protocol also includes Isle of Wight IFA placements under separate contractual arrangements. CONTENTS Section 1 Origins & Aims of Staying Put Arrangement Section 2 Establishing a Staying Put Arrangement Section 3 Roles & Responsibilities Section 4 Finance Section 5 Additional Support Section 6 Monitoring & Reviewing a Staying Put Arrangement Section 7 Ending a Staying Put Arrangement Appendix 1 Fees Appendix 2 Staying Put Agreement Appendix 3 Definitions of a Staying Put Arrangement Appendix 4 HMRC Guidance 1 “Staying Put” Protocol The arrangements for care leavers aged 18 and above to stay on with their former foster carers. Section One: Origins & Aims of Staying Put Arrangement Introduction: The Independent Fostering Agencies and Authorites of the South Central Framework have agreed this protocol which outlines staying put arrangements for young people in IFA placements. The protocol has been jointly developed by a representative group of Local Authorities and Independent Fostering Agencies. Arrangements for staying put with IFA carers will, in all cases, be discussed and agreed between the authority and The IFA. Direct approaches to and arrangements with IFA carers should not be made by Local Authorities. 1. Origin & Aims of Staying Put 1.1 The primary aim of Staying Put is to promote a gradual transition for young people from care to adulthood and independent living.