Book Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Veranstaltungen in Der Probstei 01

VERANSTALTUNGEN IN DER PROBSTEI 01. September – 31. Dezember 2019 MAXIM KOWALEW DON KOSAKEN Freitag, 6. Dezember Hotel am Rathaus, Schönberg Kowalew © www.veranstaltungen.probstei.de Kaffeeküste PRIVATRÖSTEREI LABOE Kaffeespezialitäten von Hand geröstet in Laboe Erleben Sie live wie der perfekte Kaffee entsteht. Im traditionellen Trommelröster entwickelt die Bohne ihr mildes Aroma. In unserem Café können Sie unsere Spezialitäten auch direkt genießen. Kaffeeküste Privatrösterei Laboe GmbH Parkstr. 4 • 24235 Laboe • Tel. 04343-4945595 www.kaffeekueste.de Lachmöwen Theater GODE GEISTER Komödie von Pam Valentine Ndt. von Hartmut Cyriacks und Peter Noissen 20.07. bis 30.10.2019 Karten unter Tel. 0 4343/4946440 oder www.lachmoewen.de Lachmöwen Theater Katzbek 4 · 24235 Laboe Besuchen Sie auch unsere Gastronomie: 1,5 Stunden vor Vorstellungsbeginn. Ab 14.30 Uhr vor den Vorstellungen am Sonntagnachmittag. 2 Was ist los in: Barsbek, Bendfeld, Brasilien, Brodersdorf, Fahren, Fiefbergen, Höhndorf und Gödersdorf, Hohenfelde, Holm, Kalifornien, Krokau, Krummbek und Ratjendorf, Laboe, Lutterbek, Neuschönberg, Passade, Prasdorf, Probsteierhagen, Schönberg, Schönberger Strand, Schwartbuck, Stakendorf, Stein, Stoltenberg, Wendtorf und Marina Wendtorf, Wisch und Heidkate Sonntag, 01.09.2019 08:30 Yoga auf der Seebrücke Schönberg Hatha Yoga. Kosten: 14 € /10 € ermäßigt. Seebrücke Wenn vorhanden, bitte Yoga-Matte mitbringen. Anmeldung: 0178/3129521. Nicht bei Regen. Anfänger herzlich willkommen. 09:00 Die Ostsee tanzt Schönberg Hochklassiges Tanzturnier für Senioren. Festsaal Ostsee- Wettkämpfe in Standard- und Lateintänzen für Ferienpark Holm verschiedenen Altersklassen. Tageskarte 10 € 09:30 Trau Dich und probier's doch mal! Schönberg Windsurf- oder Segelkurs für Schwimmer von WETWIND-Beach, 6-99 Jahren. Badekleidung nicht vergessen. Strandterrasse Schuhe möglichst mitbringen, Neoprenanzug leihen wir Euch. -

Radfahren in Der Probstei (3,4 Mib)

Unsere Vermieter vor Ort sind für Sie da Entfernung zum Fahrradvermietung und -reparatur mit E-Bikes Bett & Bike Betriebe Ostseeküsten-Radweg Der Ort für • Ostsee-Fahrradvermietung Gerd Schäfer • Hotel-Restaurant „Witt‘s Gasthof“ 5 km schönste Hänger/Parkplatz 2/Ostseeklinik, Im Dorfe 9, 24217 Krummbek 24217 Schönberg-Holm Tel. 04344/1568 Tel. 04344/5108 oder 0151/12348497 www.witts-gasthof.de Radtouren • Zweiradhaus Probstei, Bernd Schmidt √ • Ferienwohnung Riitta 3 km Georg-Thorn-Str. 4, 24217 Schönberg Strandstr. 214, 24217 Neuschönberg Tel. 04344/2810 oder 0171/1805259 Tel. 04385/1008 www.zweiradhaus-probstei.de www.fe-wo-ostsee.com • Fahrradvermietung Geert Gnutzmann √ • Jugendherberge Schönberg 3,5 km Seesternweg 2, 24217 Schönberg-Kalifornien Stakendorfer Weg 1, 24217 Schönberg Tel. 04344/2221 Tel. 04344/2974 ohne Reparatur www.jugendherberge.de/jh/schoenberg • Fahrradverleih Jens Wetzel √ • Naturfreundehaus Kalifornien 0,1 km Törn 7, 24235 Marina Wendtorf Deichweg 1, 24217 Schönberg-Kalifornien Tel. 0152/02583451 – ohne Reparatur im Juli/Aug. Tel. 04344/1342 www.fahrradverleih-wendtorf.de www.naturfreundehaus-kalifornien.de • Fahrradvermietung Laboe, Dirk Rothöft √ • Pension Seemöwe 0,1 km Strandstr. 28, 24235 Laboe Deichweg 4, 24217 Schönberg-Kalifornien Tel. 04343/7002 oder 0171/2151780 Tel. 04344/41690 www.fahrradverleih-laboe.de Noch www.ostsee-pension-seemoewe.de • Fahrradvermietung Hörster leichter • Fischerwiege am Passader See 7 km Strandstr. 14, 24235 Laboe unterwegs An de Laak 11, 24253 Passade Tel. 04343/494735 Tel. 04344/4138616 www.fi scherwiege-passade.de LADESTATIONEN: Fahren, Heikendorf, Hohenfelde, Krummbek, • Ferienwohnung Hof Wiese 0,6 km Kiek Laboe, Mönkeberg, Probsteierhagen, Schönberg, Schönkirchen Oberdorf 18, 24235 Laboe mol an! Tel. 04343/1001 © SECRA GmbH, Sierksdorf | Foto: SECRA GmbH, Archiv Probstei Tourismus Marketing GbR, Ostsee-Holstein-Tourismus e.V. -

Entwurf (Amt Probstei in Schönberg / Holstein)

Satzung über die Erhebung einer Hundesteuer in der Gemeinde [Name einfügen] (HundeStSa 2010) Aufgrund des § 4 der Gemeindeordnung für Schleswig-Holstein in der Fassung der Bekanntmachung vom 28.02.2003 (GVOBl. Schleswig-Holstein 2003, S. 57), zuletzt geändert durch Gesetz vom 26.03.2009 (GVOBl. 2009, S. 93) und der §§ 1 und 3 des Kommunalabgabengesetzes des Landes Schleswig-Holstein (KAG) in der Fassung der Bekanntmachung vom 10.01.2005 (GVOBl. Schleswig- Holstein 2005, S. 27), zuletzt geändert durch Gesetz vom 20.07.2007 (GVOBl. 2007, S. 362), wird nach Beschlussfassung durch die Gemeindevertretung vom TT.MM.JJJJ folgende Satzung erlassen: § 1 Steuergläubigerin Die Gemeinde [Name einfügen] (Steuergläubigerin) erhebt eine Hundesteuer als örtliche Aufwands- teuer im Sinne des Artikels 105 Abs. 2 a des Grundgesetzes. § 2 Begriffsbestimmungen [1] Halten eines Hundes ist die Aufnahme eines Hundes in den Haushalt oder Wirtschaftsbetrieb im eigenen Interesse oder im Interesse von Angehörigen für einen nicht nur vorübergehenden Zeitraum. [2] Halter eines Hundes ist jede natürliche Person, die einen Hund in ihrem eigenen Interesse oder im Interesse ihrer Angehörigen in ihren Haushalt oder Wirtschaftsbetrieb aufnimmt. Halter eines Hundes ist auch eine natürliche Person, mit deren Einverständnis oder Duldung der Hund in den Haushalt oder den Wirtschaftsbetrieb aufgenommen wird. Als Halter eines Hundes gilt auch eine natürliche Person, die einen Hund in Pflege oder Verwahrung genommen hat oder auf Probe oder zum Anlernen aufgenommen hat, wenn sie nicht nachweisen kann, dass die Haltung des Hundes in einer anderen inländischen Gemeinde der Steuerpflicht unterliegt oder von der Besteuerung befreit ist. Es wird unwi- derlegbar vermutet, dass der Hund gehalten wird, wenn die Pflege, Verwahrung oder die Haltung auf Probe oder zum Anlernen im Sinne des Satzes 2 den Zeitraum von zwei Monaten überschreitet. -

Jagd Und Artenschutz Herausgeber: Ministerium Für Energiewende, Landwirtschaft, Umwelt Und Ländliche Räume Des Landes Schleswig-Holstein Mercatorstraße 3 24106 Kiel

Ministerium für Energiewende, Landwirtschaft, Umwelt und ländliche Räume Jahresbericht 2012 Jagd und Artenschutz Herausgeber: Ministerium für Energiewende, Landwirtschaft, Umwelt und ländliche Räume des Landes Schleswig-Holstein Mercatorstraße 3 24106 Kiel Titelfoto: „Koniks als Landschaftspfleger“ von Dr. Helge Neumann „Jagdliches Schießen“ von Frank Schmidt LJV Schleswig-Holstein Zeichnungen: Dr. Winfried Daunicht und Kenneth-Vincent Daunicht Druck: Pirwitz Druck & Design, Kiel November 2012 ISSN 1437-868X Auflage: 5.000 Diese Broschüre wurde auf 100% chlorfrei gebleichtem Papier (tcf) gedruckt. Diese Druckschrift wird im Rahmen der Öffentlichkeitsarbeit der Schleswig-Holsteinischen Landesregierung herausgegeben. Sie darf weder von Parteien noch von Personen, die Wahlwerbung oder Wahlhilfe betreiben, im Wahlkampf zum Zwecke der Wahlwerbung verwendet werden. Auch ohne zeitlichen Bezug zu einer bevorstehenden Wahl darf die Druckschrift nicht in einer Weise verwendet werden, die als Parteinahme der Landesregierung zugunsten einzelner Gruppen verstanden werden könnte. Den Parteien ist es gestattet, die Druckschrift zur Unterrichtung ihrer eigenen Mitglieder zu verwenden. Die Landesregierung im Internet: http://www.schleswig-holstein.de Inhalt Vorwort.......................................................................................................................................5 1 Jagd 1.1 Niederwild .............................................................................................................................6 1.1.1 -

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Inhaltsverzeichnis. Seite Einleitung XIII Etwas über Wald- und Wegverbote XXXIV Allgemeines XXXV Literatur XXXVI I. Kiel 1—5 1. Gang durch die Stadt und durch Düsternbrook. 3 2. Die Fahrt auf dem Hafen 3 3. Zum Kaiser-Wilhelm-Kanal 4 II. Die Probstel 5—10 1. Strandwanderung: Laboe—Stein—Kolberger Heide —Schönberger Strand 6 2. Mit der Bahn nach Schönberg; dann zum Strande 7 3. Von Schönberg nach dem Hessenstein .... 8 4. Hagen, Probsteierhagen; an der Hagener Au ent- lang 9 III. Dobersdorfer und Fassader See 10—14 1. Von Schönkirchen nach Tökendorf—Dobersdorf . 10 2. Von der Schwentine an den Dobersdorfer See . 11 3. Von Mörken nach Dobersdorf—Tökendorf ... 12 4. Von Mörken nach Schlesen 13 5. Von Schlesen nach Tökendorf—Probsteierhagen . 13 6. Von Schlesen nach Passade 13 IV. Selenter See 14—18 1. Von Schlesen nach Fargau 14 2. Von Neuenkrug nach Fargau 15 3. Salzau 15 4. Ausflug in die Gehege Adelinental und Stauen am Selenter See 16 5. Von Fargau nach der Schmützeiche und weiter nach Charlottenthal—Stoltenberg (Passade) ... 16 6. Von Fargau nach Selent—Blomenburg .... 17 Y. Schierensee und Westensee 18—25 1. Von Voorde nach Schierensee 18 2. Südlich und westlich um die Schierenseen durch den Börner nach Hohenhude 19 http://d-nb.info/361732597 Inhaltsverzeichnis. Seite 3. Von Schierensee nach Hohenhude mit Abstecher nach dem Blotenberge 20 4. Von Hohenhude nach Kiel bzw. an die Bahn. 21 5. Von Kiel nach Westensee 22 6. Von Westensee nach dem Tüteberg und den Hünen- gräbern bei Deutsch-Nienhof (und wieder nach Westensee) - 23 7. -

Heikendorf Schönkirchen

Kunstkiosk U-Boot 1 Ehrenmal Möltenort 2 Infopavillon Fischerei Neuheikendorf 3 Heikendorf Altheikendorf Seebadeanstalt 5 Künstler- museum Irrgarten 4 Kitzeberg Schrevenborn Probsteierhagen Schloss Hagen 6 Gut Unterdorf Germania- koppel Mönkeberg Oberdorf 7 Bake Stangenberg Ölberg Landgraben Mönkeberger See Schönkirchen Schmidt-Haus Schönhorst Neumühlen- Dietrichsdorf Dorfteich, Hörn Huus, Gildehaus Marienkirche Schwentine Bürger- wald Anschütz- siedlung Schwentine- Schrevenborner Rund brücke Schwentinewasser- wanderweg Maritim Route Kiel-Oppendorf Hof Schönhorst Wellingdorf Kirchenroute Brottour Ostseeküstenradweg / Fördewanderweg Heikendorfer Wasserweg Schwentinewanderweg / E1 / Via Jutlandica Schusteracht Schwentinerunde Kiel Oppendorf Naturlehrpfad Schönkirchen Ellerbek Grüne Wege Gut 1 Ahorn 2 Linde 3 Kastanie 4 Eiche 5 Ginko 6 Buche 7 Weide Schwentinental Fähre Strand/Baden Hafen Aussichtspunkt Ortsteil Klausdorf Flüggendorf Gastro Regionalbahn Kirche Einkaufen Kultur Tourist-Info Golf Museumsbahn Elmschenhagen Camping Schwentinetalfahrt Seebadeanstalt SprottenFlotte (Bike-Sharing) Map data © www.openstreetmap.org; www.opendatacommons.org Oppendorfer Mühle © www.kaniess-druck.de · © Icons teilw.: freepik.com . -

La 12-17.Cdr

aboe aktuell Monatsmagazin der Gemeinde Ostseebad Laboe Weiße Winterwelt 12/17 sicher schnell zuverlässig Inh.: N. Szupryczynski Kanalreinigung + Containerdienst Am Jahresende danken wir für das entgegengebrachte Vertrauen und die gute Zusammenarbeit. Wir wünschen unseren Kunden, Geschäftsfreunden und Bekannten ein frohes Weihnachtsfest, viel Glück und Erfolg im neuen Jahr. Vielen Dank für das entgegengebrachte Vertrauen im Jahr 2015. Schminkworkshop zur KielerWir wünschen Woche allen Unter dem Thema >perfektKunden undgestylt Geschäf fürtsfreunden die Kieler Woche < luden Tanja eineDuchateau besinnliche und Angela Wöhlk zum erstenAdvents- Mal und zehn Weihnachtszeit Schü- lerinnen der Klassenstufensowie Gesundheit, 8 - 10 der Glück Grund- und Erfolg und Gemeinschaftsschule Heikendorfim neuen Jahr! am Dienstag, den 24. Juni 2014 in die Räume der OGTS (Offene Ganztagsschule)Ihr Team der Auto gazuler ieeinem Probst eierhagen Schminkworkshop ein. die Erstklässler herzlich willkommen und Unter der fachlichen Anleitung von Nadine Tel.: 0 43 07 / 82 88 88wünscht + 04eine gute31 Grundschulzeit. / 79 456 Kohn-Peters und ihrer Mitarbeiterinwww.autogalerie-probsteierhagen.de Astrid • Telefon/Werkstatt 91 91 12 Lise-Meitner-Straße 13 24223 Schwentinental www.absolut-kanal.de Walter aus der Parfümerie und dem Kos- Das Kollegium der GS Laboe metikinstitut Kohn, Am Schmiedeplatz 2 in Heikendorf, erlernten sie Schritt für Schritt, wie man durch Make-up seinem Gesicht eine frische Ausstrahlung verleiht Das gesamte Zubehör brachte Frau Kohn- Peters dafür extra in die OGTS und baute für jede Schülerin einen Schminktisch auf. Außerdem erhielt jede Schülerin ein 14teili- „Ein frohes Fest sowie einen ges Pinselset, welches sie auch mit nach Hau- ruhigen Jahresausklang se nehmen durften. Nach zwei fröhlichen Stunden und individu- wünscht Ihnen Ihr Pfl egeteam eller Beratung hatten alle Teilnehmerinnen von der ein superschönes Ergebnis erzielt. -

Kieler Woche 2019 RB 76 Kiel - Schönberg (Holstein) - Schönberger Strand Fr 21.6.- Mo 1.7.2019 2:00 Uhr

133 Kieler Woche 2019 RB 76 Kiel - Schönberg (Holstein) - Schönberger Strand Fr 21.6.- Mo 1.7.2019 2:00 Uhr Stand 5.3.2019 Kieler Woche Zusatzverkehr, gültig Fr 21.6.2019 15:00 - Mo 1.7.2019 2:00 RB76 RB76 RB76 RB76 RB76 RB76 RB76 RB76 RB76 RB76 RB76 RB76 RB76 RB76 RB76 Zugtyp RB RB RB RB RB RB RB RB P RB RB RB RB P RB RB RB Zugnummer 11957 11959 11961 11963 11965 11967 11969 11969 1003 21559 11971 11973 11973 1005 21543 11975 11977 Verkehrstag Mo-Fr Mo-Fr Mo-Sa Mo-Sa Mo-Sa Mo-Sa Mo-Fr Sa+So Sa+So Sa+So TGL Mo-Fr Sa+So Sa+So Sa+So TGL Mo-Do km Von: 0 Kiel Hbf 5:24 6:07 7:24 8:07 9:07 10:07 11:07 11:07 11:24 12:07 13:07 13:07 13:24 14:07 15:07 4 Kiel Schulen am Langsee X 5:29 X 6:12 7:30 X 8:12 X 9:12 X 10:12 X 11:12 X 11:12 X 11:29 X 12:12 X 13:12 X 13:12 X 13:29 14:12 X 15:12 6 Kiel-Ellerbek 5:31 6:14 7:32 8:14 9:14 10:14 11:14 11:14 11:31 12:14 13:14 13:14 13:31 14:14 15:14 9 Kiel-Oppendorf o 5:35 o 6:18 o 7:36 o 8:18 o 9:18 o 10:18 o 11:18 11:19 o 11:35 o 12:18 o 13:18 13:19 o 13:35 o 14:18 o 15:18 11 Schönkirchen 11:23 13:23 16 Probsteierhagen 11:38 13:38 18 Passade | | 20 Fiefbergen | | 22 Schönberg (Holst.) o 11:53 13:53 Schönberg (Holst.) 12:15 14:15 24 Stakendorf 12:23 14:23 26 Schönberger Strand o 12:30 14:30 Nach: RB76 RB76 RB76 RB76 RB76 RB76 RB76 RB76 RB76 RB76 RB76 RB76 RB76 RB76 RB76 Zugtyp RB RB RB RB RB RB RB RB RB RB RB P RB RB RB RB P Zugnummer 11988 11950 11952 11954 11956 21558 11958 11958 11960 21538 11962 1002 11962 11964 21540 11966 1004 Verkehrstag Mo-Fr Mo-Fr Mo-Sa Mo-Sa Mo-Sa Sa Mo-Fr Sa+So TGL Sa+So Mo-Fr Sa+So -

Satzung Des Kreises Plön Über Die Benutzung Des Rettungsdienstes (Rettungsdienstsatzung)

Öffentliche Bekanntmachung des Kreises Plön LfdNr./Jahr 1-5 Veröffentlichungsdatum: 20.07.2015 23 / 2015 Satzung des Kreises Plön über die Benutzung des Rettungsdienstes (Rettungsdienstsatzung) Aufgrund des § 4 der Kreisordnung für Schleswig-Holstein (KrO) vom 28.02.2003 (GVOBl. SH 2003 S. 94) in der derzeit gültigen Fassung und des Rettungsdienstgesetzes des Landes Schleswig-Holstein (RDG SH) vom 29.11.91 (GVOBl. SH S. 579) in der derzeit gültigen Fassung hat der Kreistag des Kreises Plön in seiner Sitzung am 09.07.2015 folgende Satzung beschlossen: § 1 Träger des Rettungsdienstes und Geltungsbereich der Satzung (1) Der Kreis Plön ist gem. § 6 Abs. 2 RDG SH Träger des Rettungsdienstes für sein Kreisgebiet. (2) Mit der Durchführung des Rettungsdienstes sind gem. § 6 Abs. 3 Satz 1 Nr. 2 RDG die Gesundheits- und Pflegeeinrichtungen des Kreises Plön gGmbH für die Notfallrettung und den Krankentransport in den Rettungswachenbereichen Lütjenburg, Preetz und Probsteierhagen sowie für die Notarztversorgung von den Standorten Preetz und Stakendorf aus, für die Notfallrettung und den Krankentransport im Rettungswachenbereich Plön die Johanniter-Unfall-Hilfe e. V. - Regionalverband Schleswig-Holstein Nord/West - beauftragt. (3) Die Satzung gilt für die Inanspruchnahme des Rettungsdienstes des Kreises Plön bei Wahrnehmung durch den Kreis selbst sowie im Fall der Übertragung auf Dritte gem. § 6 Abs. 3 RDG SH im Kreisgebiet. (4) Gemäß §§ 18 und 19 des Gesetzes über kommunale Zusammenarbeit (GkZ) hat der Kreis Plön mit den Kreisen Ostholstein, Rendsburg-Eckernförde und Segeberg sowie den kreisfreien Städten Kiel und Neumünster öffentlich-rechtliche Vereinbarungen getroffen, die sich auf den Geltungsbereich dieser Satzung auswirken. Näheres regeln die Absätze 5 bis 9. -

Pressemitteilung (Word)

Pressemitteilung Glasfaserausbau Probstei – Startschuss für Aktionsgebiet Zwei • Vermarktung im zweiten Aktionsgebiet startet Ende April • Bürgerinnen und Bürger können sich kostenlosen Glasfaseranschluss sichern • Beratungstermine in den Gemeinden beginnen am 28. April Kiel, 25.04.2018 – Nach dem ersten Aktionsgebiet startet Ende des Monats auch Gebiet Zwei in die Vermarktung für das Solidarprojekt „Glasfaserausbau in der Probstei“. Gemeinsam mit dem Breitbandzweckverband Probstei lädt die TNG Stadtnetz GmbH in dieser Woche zu mehreren Informationsveranstaltungen ein und bietet ab der kommenden Woche zahlreiche Beratungstermine in den Gemeinden Fahren, Fiefbergen, Höhndorf, Lutterbek, Passade, Prasdorf und Stoltenberg an. „Wir erfahren eine große Unterstützung aus den Gemeinden und freuen uns nun darauf, auch die Bürgerinnen und Bürger für den Bau eines flächendeckenden, kommunalen Breitbandnetzes zu begeistern, das unsere Region mit schnellem Internet versorgen und damit fit für die Anforderungen der Zukunft machen wird“, sagt Wolf Mönkemeier, Verbandsvorsteher des BZV Probstei. Den Beginn der Vermarktung in jedem Gebiet macht stets eine Reihe von Informationsveranstaltungen, die in dieser Woche u.a. in Stoltenberg (25. April, 19 Uhr, Dorfgemeinschaftshaus, Dorfstraße 6) und Höhndorf (26. April, 19 Uhr, Dorfgemeinschaftshaus, Schulkoppelweg 4) stattfinden. Ab Samstag, den 28. April bieten TNG-Mitarbeiter bei zahlreichen Beratungsterminen die Möglichkeit, sich über einen Glasfaseranschluss zu informieren und Verträge abzugeben. Vertragsabschlüsse sind außerdem auch bequem von zuhause - online unter www.tng.de/onlinebestellung - möglich. Erste Beratunstermine finden an folgenden Terminen statt: Samstag, 28. April, 10-13 Uhr, Prasdorf – Dörpshus, Dorfstraße 29 Mittwoch, 9. Mai, 16-19 Uhr, Fiefbergen – Dorfgemeinschaftshaus, St. Florian-Weg 1 Freitag, 11. Mai, 15-18 Uhr, Höhndorf – Dorfgemeinschaftshaus, Schulkoppelweg 4 Samstag, 12. Mai, 10-13 Uhr, Prasdorf – Dörpshus, Dorfstraße 29 Dienstag, 15. -

Kanus, Kajaks, Kilometer

Wasserwege in Schleswig-Holstein Kanus, Kajaks, Kilometer 1 1 2 2 Liebe Kanuwanderinnen, liebe Kanuten Sport und Naturschutz haben ein ge- Wer mit dem Boot ein Gewässer meinsames Anliegen: die Natur, ihre befährt, ist ganz dicht dran an der Schönheiten und ihren Erholungs- Natur. Tipps und Hinweise in der wert zu erhalten. neuen Broschüre helfen daher, die Natur vom Wasser aus zu entde- Der Wassersport ist in Schleswig- cken, ihre Schönheit zu genießen Holstein fester Bestandteil der und sie gleichzeitig zu schonen. Be- naturnahen Erholung. Das Land lohnt wird man dann eventuell auch zwischen den Meeren wird auch im durch den Anblick eines Eisvogels, Landesinneren immer wieder vom einer Prachtlibelle oder einer selte- Wasser geprägt. Flüsse und Seen nen Pflanze am Schilfrand. reagieren als wertvolle biologische Lebensräume jedoch auch empfind- Ich wünsche in diesem Sinne allen lich auf Störungen. Die Ansprüche Kanuwanderinnen und Kanuten im- von Natur und Landschaft und die mer genügend Wasser unter dem Erholung in der freien Natur oder auf Boot und viele beeindruckende dem Wasser müssen daher mitein- Naturerlebnisse auf unseren schö- ander in Einklang gebracht werden. nen Gewässern im „Wasserland“ Schleswig-Holstein. Bereits seit dem Jahr 2001 arbeiten die Kanusportverbände und mein Ministerium intensiv zusammen. Vereinbart wurde damals eine umweltverträgliche Nutzung der befahrbaren Gewässer in Schleswig- Holstein. Darauf folgte im Jahr 2008 eine Rahmenvereinbarung über „Na- tura 2000 und Sport in Schleswig- Holstein“. Dr. Juliane Rumpf Ministerin für Landwirtschaft, Um- Auch die Neuauflage dieser viel ge- welt fragten Broschüre ist wieder durch und ländliche Räume Kooperation des Ministeriums für des Landes Schleswig - Holstein Landwirtschaft, Umwelt und ländli- che Räume mit allen interessierten Sportverbänden entstanden. -

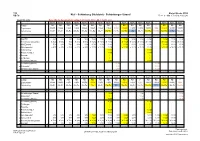

Beherbergung Im Reiseverkehr in Schleswig-Holstein 2018

Statistisches Amt für Hamburg und Schleswig-Holstein STATISTISCHE BERICHTE Kennziffer: G IV 1 - j 18 SH Beherbergung im Reiseverkehr in Schleswig-Holstein 2018 Herausgegeben am: 27. März 2019 Impressum Statistische Berichte Herausgeber Statistisches Amt für Hamburg und Schleswig-Holstein – Anstalt des öffentlichen Rechts – Steckelhörn 12 20457 Hamburg Auskunft zu dieser Veröffentlichung: Michael Schäfer Telefon: 0431 6895-9231 E-Mail: [email protected] Auskunftsdienst E-Mail: [email protected] Auskünfte: 040 42831-1766 Internet: www.statistik-nord.de © Statistisches Amt für Hamburg und Schleswig-Holstein, Hamburg 2019 Auszugsweise Vervielfältigung und Verbreitung mit Quellenangabe gestattet. Sofern in den Produkten auf das Vorhandensein von Copyrightrechten Dritter hingewiesen wird, sind die in deren Produkten ausgewiesenen Copyrightbestimmungen zu wahren. Alle übrigen Rechte bleiben vorbehalten. Zeichenerklärung 0 weniger als die Hälfte von 1 in der letzten besetzten Stelle, jedoch mehr als nichts – nichts vorhanden (genau Null) ··· Angabe fällt später an · Zahlenwert unbekannt oder geheim zu halten x Tabellenfach gesperrt, weil Aussage nicht sinnvoll p vorläufiges Ergebnis r berichtigtes Ergebnis s geschätztes Ergebnis a. n. g anderweitig nicht genannt u. dgl. und dergleichen Statistikamt Nord 2 Statistischer Bericht G IV 1 - j 18 SH Inhaltsverzeichnis Seite Rechtsgrundlagen, Erläuterungen 4 Anhang: Gemeinden nach der Gemeindegruppe 55 Tabellen 1 Beherbergungsangebot sowie Ankünfte, Übernachtungen und Aufenthaltsdauer