War on Terror Partnership and Growing/Mounting/Increasing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Caiozzo & Duchêne

Stéphane A. Dudoignon « Le gnosticisme pour mémoire ? Déplacements de population, histoire locale et processus hagiographiques en Asie centrale postsoviétique » in A. Caiozzo & J.-C. Duchène, éd., La Mongolie dans son espace régional : Entre mémoire et marques de territoires, des mondes anciens à nos jours Valenciennes : Presses de l’Université de Valenciennes, 2020 : 261–93, ill. Le rôle d’une variété de marquages territoriaux, notamment culturels (sanctuaires et lieux de mémoire, en particulier) en Asie centrale est au cœur de recherches saisonnières que l’auteur de ces lignes a entreprises ou dirigées à partir de l’automne 2004 1. Individuels et collectifs, ces travaux visaient à promouvoir une géohistoire de l’islam en général, du soufisme spécialement, et de ses sociabilités gnostiques, en Asie centrale soviétique et actuelle. Cette recherche était axée sur l’étude des manières dont les pratiques et identités religieuses s’inscrivent dans une grande diversité de territoires, dans un contexte marqué, depuis le lendemain de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, par les impacts des répressions des années 1920 et 30, puis des déplacements massifs de populations des années 40-50 et par la création de nouvelles communautés territorialisées dans le cadre du système des fermes collectives. En grande partie inédite, interrompue un temps après 2011 par la dégradation du climat politique dans la région et une prévention générale envers la recherche internationale, ce travail s’est focalisé sur l’analyse d’un ensemble de processus hagiographiques dont le rapide développement a pu être observé dans cette partie du monde à partir de la chute du Mur, en novembre 1989, puis la dissolution de l’URSS deux ans plus tard. -

Chapter VI Conclusions

Chapter VI Conclusions Trade and commerce of Adil Shahi Sultanate was gradually increasing through various stages, but it reached to a height after the fall of Barid Shahi and Vijaynagar. The establishment of Bahmani rule had removed Bijapur’s status as a remote frontier post, however, under the Bahamanis Bijapur never possessed the economic or political importance of Gulbarga and Bidar, the two Bahmani capitals. Bijapur’s de facto independence (1490), from Bahmani authority could not suddenly transform the city into a notable centre of Islamic civilization. One political city had to fall or decline so that a new political city rose and grew in its stead. Bidar was declined in the last quarter of 15th century and Vijaynagar was destroyed by confederate Muslim states of the Deccan in the battle of Talikota in 1565 and on its ashes raised the glory of Bijapur. By the end of sixteenth century Bijapur had emerged as one of the major Islamic urban centres. The early seventeenth century saw the peak growth of the city’s population, on the basis of the estimation of James Campbell, two million of population was resided within and outside of fort of Bijapur. Under the aegis of Ibrahim II and Muhammad Adil Shah, Bijapur’s significance in all respects grew further and it became an important city of the Deccan. Migration of Qadiri Sufis into the Bijapur during this period could be seen as an important indicator of urbanization. After the fall of Vijaynagar the resources of sultanate increases and Karwar, Honawar and Bhatkal came in their possession which helps to boost up their trade and 548 J.D.B., Gribble, History of the Deccan, op. -

The Culmination of Tradition-Based Tafsīr the Qurʼān Exegesis Al-Durr Al-Manthūr of Al-Suyūṭī (D. 911/1505)

The Culmination of Tradition-based Tafsīr The Qurʼān Exegesis al-Durr al-manthūr of al-Suyūṭī (d. 911/1505) by Shabir Ally A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations University of Toronto © Copyright by Shabir Ally 2012 The Culmination of Tradition-based Tafsīr The Qurʼān Exegesis al-Durr al-manthūr of al-Suyūṭī (d. 911/1505) Shabir Ally Doctor of Philosophy Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations University of Toronto 2012 Abstract This is a study of Jalāl al-Dīn al-Suyūṭī’s al-Durr al-manthūr fi-l-tafsīr bi-l- ma’thur (The scattered pearls of tradition-based exegesis), hereinafter al-Durr. In the present study, the distinctiveness of al-Durr becomes evident in comparison with the tafsīrs of al- a arī (d. 310/923) and I n Kathīr (d. 774/1373). Al-Suyūṭī surpassed these exegetes by relying entirely on ḥadīth (tradition). Al-Suyūṭī rarely offers a comment of his own. Thus, in terms of its formal features, al-Durr is the culmination of tradition- based exegesis (tafsīr bi-l-ma’thūr). This study also shows that al-Suyūṭī intended in al-Durr to subtly challenge the tradition- ased hermeneutics of I n Taymīyah (d. 728/1328). According to Ibn Taymīyah, the true, unified, interpretation of the Qurʼān must be sought in the Qurʼān ii itself, in the traditions of Muḥammad, and in the exegeses of the earliest Muslims. Moreover, I n Taymīyah strongly denounced opinion-based exegesis (tafsīr bi-l-ra’y). -

Religion and Politics: a Study of Sayyid Ali Hamdani

American International Journal of Available online at http://www.iasir.net Research in Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences ISSN (Print): 2328-3734, ISSN (Online): 2328-3696, ISSN (CD-ROM): 2328-3688 AIJRHASS is a refereed, indexed, peer-reviewed, multidisciplinary and open access journal published by International Association of Scientific Innovation and Research (IASIR), USA (An Association Unifying the Sciences, Engineering, and Applied Research) Religion and Politics: A Study of Sayyid Ali Hamdani Umar Ahmad Khanday Research Scholar Department of History Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, INDIA. Abstract: Sayyid Ali Hamdani was a multi-dimensional personality. He belonged to Kubraviya order of Sufis. When he landed in Kashmir, the ethical quality was at its most reduced ebb. The pervasiveness of standings and sub-stations in the general public, misuse of ordinary citizens because of conventional Brahmins, had rendered normal individuals defenceless. Individuals were prepared to welcome any change in the framework. Under his effect, the impact of Brahmans declined. His Khanqah was available to all from the Sultan to poor Hindu. He had no reservation in counselling rulers and nobility because he saw that their policies were key to the welfare of people. He was a social reformer other than being a preacher.Among the 700 devotees, who went with him to Kashmir were men of Arts and Crafts Crafts, as a result, several industries of Hamadan (Iran) became well introduced in Kashmir. Key Words: Khanqah, Rights,Ruler, Sayyid Ali Hamdani,Sufi ,Zakhiratul-Muluk I. Introduction Sayyid Ali Hamdani, who belonged to the family of Alawi Sayyids1 was born on 12 Rajab, 714/22 October, 1314 at Hamdan2. -

Cultural Festivals: an Impotent Source of De-Radicalization Process in Pakistan: a Case Study of Urs Ceremonies in Lahore City

Journal of the Punjab University Historical Society Volume No. 03, Issue No. 2, July - December 2017 Syed Ali Raza* Cultural Festivals: An Impotent Source of De-Radicalization Process in Pakistan: A Case Study of Urs Ceremonies in Lahore City Abstract The Sufism has unique methodology of the purification of consciousness which keeps the soul alive. The natural corollary of its origin and development brought about religo-cultural changes in Islam which might be different from the other part of Muslim world. Sufism has been explained by many people in different ways and infect is the purification of the heart and soul as prescribed in the holy Quran by God. They preach that we should burn our hearts in the memory of God. Our existence is from God which can only be comprehended with the help of blessing of a spiritual guide in the popular sense of the world. Sufism is the way which teaches us to think of God so much that we should forget our self. Sufism is the made of religious life in Islam in which the emphasis is placed, not on the performance of external ritual but on the activities of the inner-self’ in other words it signifies Islamic mysticism. Beside spirituality, the Sufi’s contributed in the promotion of performing art, particularly the music. Pakistan has been the center of attraction for the Sufi Saints who came from far-off areas like Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan and Arabia. The people warmly welcomes them, followed their traditions and preaching’s and even now they celebrates their anniversaries in the form of Urs. -

Dynastic Lists and Genealogical Tables

DYNASTIC LISTS AND GENEALOGICAL TABLES (1) The Bahamani Dynasty of the Deccan. (2) The Nizam Shahi Dynasty of Ahmadnagar. (3) The Adil Shahi Dynasty of Bijapur. (4) The Imad Shahi Dynasty of Berar. (5) The Qutb Shahi Dynasty of Golconda. (6) The Barid Shahi Dynasty of Bidar. (7) The Faruqi Dynasty of Khandesh. 440 DYNASTIC LISTS AND GENEALOGICAL TABLES THE BAHAMANI DYNASTY OF THE DECCAN Year of Accession Year of Accession A. H. A. D. 748 Ala-ud-din Bahman Shah 1347 759 Muhammad I 1358 776 Mujahid 1375 779 Daud 1378 780 Mahmud (wrongly called Muhammad II) . 1378 799 Ghiyas-ud-din 1397 799 Shams-ud-din 1397 800 Taj-ud-din-Firoz 1397 825 Ahmad, Vali 1422 839 Ala-ud-din Ahmad 1436 862 Humayun Zalim 1458 865 Nizam 1461 867 Muhammad III, Lashkari 1463 887 Mahmud 1482 924 Ahmad 1518 927 Ala-ud-din 1521 928 Wali-Ullah 1522 931 Kalimullah 1525 944 End of the dynasty 1538 DYNASTIC LISTS AND GENEALOGICAL TABLES 441 THE BAHAMANI DYNASTY OF THE DECCAN GENEALOGY (Figures in brackets denote the order of succession) 442 DYNASTIC LISTS AND GENEALOGICAL TABLES THE NIZAM SHAHI DYNASTY OF AHMADNAGAR Year of Accession Year of Accession A. H. A. D. 895 Ahmad Nizam Shah 1490 915 Burhan Nizam Shah I 1509 960 Husain Nizam Shah I 1553 973 Murtaza Nizam Shah I 1565 996 Husain Nizam Shah II 1588 997 Ismail Nizam Shah 1589 999 Burhan Nizam Shah II 1591 1001 Ibrahim Nizam Shah 1594 1002 (Ahmad-usurper) 1595 1003 Bahadur Nizam Shah 1595 1007 Murtaza Nizam Shah II 1599 1041 Husain Nizam Shah III 1631 1043 End of the Dynasty 1633 DYNASTIC LISTS AND GENEALOGICAL TABLES 443 444 DYNASTIC LISTS AND GENEALOGICAL TABLES THE ADIL SHAHI DYNASTY OF BIJAPUR Year of Accession Year of Accession A. -

Boctor of $F)Ilos(Op})P I Jn M I I

SUFI THOUGHT OF MUHIBBULLAH ALLAHABADI Abstract Thesis SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Boctor of $f)ilos(op})p I Jn M I I MOHD. JAVED ANS^J. t^ Under the Supervision of Prof. MUHAMMAD YASIN MAZHAR SIDDiQUi DEPARTMENT OF ISLAMIC STUDIES ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2006 Abstract The seventeenth Century of Christian era occupies a unique place in the history of Indian mystical thought. It saw the two metaphysical concepts Wahdat-al Wujud (Unity of Being) and Wahdat-al Shuhud (Unity of manifestation) in the realm of Muslim theosophy and his conflict expressed itself in the formation of many religious groups, Zawiyas and Sufi orders on mystical and theosophical themes, brochures, treatises, poems, letters and general casuistically literature. The supporters of these two schools of thought were drawn from different strata of society. Sheikh Muhibbullah of Allahabad, Miyan Mir, Dara Shikoh, and Sarmad belonged to the Wahdat-al Wujud school of thought; Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi, Khawaja Muhammad Masum and Gulam Yahya belonged to the other school. Shaikh Abdul Haqq Muhaddith and Shaikh WalliuUah, both of Delhi sought to steer a middle course and strove to reconcile the conflicting opinions of the two schools. Shaikh Muhibbullah of Allahabad stands head and shoulder above all the persons who wrote in favour of Wahdat-al Wujud during this period. His coherent and systematic exposition of the intricate ideas of Wahdat- al Wujud won for him the appellation of Ibn-i-Arabi Thani (the second Ibn-i Arabi). Shaikh Muhibbullah AUahabadi was a prolific writer and a Sufi of high rapture of the 17* century. -

Copyright by Mohammad Raisur Rahman 2008

Copyright by Mohammad Raisur Rahman 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Mohammad Raisur Rahman certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Islam, Modernity, and Educated Muslims: A History of Qasbahs in Colonial India Committee: _____________________________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________________________ Cynthia M. Talbot _____________________________________ Denise A. Spellberg _____________________________________ Michael H. Fisher _____________________________________ Syed Akbar Hyder Islam, Modernity, and Educated Muslims: A History of Qasbahs in Colonial India by Mohammad Raisur Rahman, B.A. Honors; M.A.; M.Phil. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2008 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to the fond memories of my parents, Najma Bano and Azizur Rahman, and to Kulsum Acknowledgements Many people have assisted me in the completion of this project. This work could not have taken its current shape in the absence of their contributions. I thank them all. First and foremost, I owe my greatest debt of gratitude to my advisor Gail Minault for her guidance and assistance. I am grateful for her useful comments, sharp criticisms, and invaluable suggestions on the earlier drafts, and for her constant encouragement, support, and generous time throughout my doctoral work. I must add that it was her path breaking scholarship in South Asian Islam that inspired me to come to Austin, Texas all the way from New Delhi, India. While it brought me an opportunity to work under her supervision, I benefited myself further at the prospect of working with some of the finest scholars and excellent human beings I have ever known. -

Saviours of Islamic Spirit

nmusba.wordpress.com Academy of Islamic Research and Publications nmusba.wordpress.com SAVIOURS OF ISLAMIC SPIRIT VOLUME m b y S. ABUL HASAN All NADWI Translation : MOHIUDDIN AHMAD ACADEMY OF ISLAMIC RESEARCH & PUBLICATIONS P.O. Bax 119, NADWA, LUCKNOW-226 007 U. P. (INDIA) A ll rights reserved in favour of: Academy of Islamic Research and Publications Post Box No. 119, NadWatuI Ulama, LUCKNOW-23I0O7 U.P? (INDIA) at awtuo' Series No. 170 EDITtONS: URDU— FIRST EDITION 1982 ENGLISH-FIRST EDITION 1983 SECOND EDITION 1994 Printed at: LUCKNOW PUBLISHING HOUSE LUCKNOW nmusba.wordpress.com CONTENTS Page FORBWARD ... ... ••• 1 I . ISLAMIC WORLD IN THB TENTH GENTURY ... 11 Need for the Study of the Tenth Century Condition* ... ... ... ib. Political Conditions ... ... ... 12 Religious Conditions ... ... ... 16 Intellectual Milieu ... ... ... 2 5 Intellectual and Religious Disquietude ... 2 9 Mahdawls ... ... ... ... 37 Causes o f Unrest ... ... ... 42 I I . THE GREATEST TUMULT OF THB TENTH CENTURY ... 45 Advent of a New Order ... ... ib. I I I . AKBAR^S RULE— THE CONTRASTING CuMAXES ... 53 The Religious Period ... ... ... ib. The Second Phase o f Akbar’s Rule ... 6 0 Effect of Religious Discussions ... ... 61 Role o f Religious Scholars ... ... 66 Religious Scholars o f Akbar’s Court ... 68 Courtiers and Counsellors ... ... 72 ii •AVIOURI OP ISLAMIC SPIKIT Mulls Mubarak and his sons 73 Influence of Rajput Spouses 83 Infallibility Decree 84 Significance of the Decree 86 Fall of Makhdum-ul-Mulk and Sadr-us-Sudnr ... 87 The New Millennium and Divine Faith 88 Akbar's Religious ideas and Practices 90 Fire Worship ... : ib. Sun Worship 91 On Painting 92 Timings of Prayer .. -

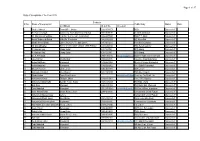

Of 17 Data of Complaints of the Year 2015 (I) Address (II) Cell No

Page 1 of 17 Data of Complaints of the Year 2015 Contacts Sr No. Name of Complainant Public Body Status Date (i) Address (II) Cell No (iii) e-mail 1 Shakeel Ahmad Dawn Office, Multan 0333-8558057 DCO Disposed off 2 Dr. Farooq Lahgah Gulraiz Cly. Allah Shafi Chwok Multan 0302-8699035 Heald Deptt Multan Disposed off 3 Ch. Muhammad Saddique H # 788, St # 16, I-8/2, Aslamabad 0306-4977944 DCO T.T. Singh Disposed off 4 Hamid Mahmood Shahid Millta Rd. Faisalabad 033-26762069 MD Wasa Fbd Disposed off 5 Bashir Ahmad Bhatti Lahore Museum, The Mall Lahore 0347-4001211 Print Media Cmpany Disposed off 6 Mir Ahmad Qamar Ali Pur Chowk, Bazar Jampur, Distt. Rajinpur 0333-6452838 TMA Tehsil Jaampur Disposed off 7 M. Kamran Saqi Jhang Sadar 301-4124790 DPO Jhang Disposed off 8 M. Kamran Saqi Jhang Sadar 301-4124790 DPO Jhang Disposed off 9 Dr. A. H. Nayyar 0300-5360110 [email protected] solar Power Ltd Disposed off 10 Javed Akhtar Muzafarghar 0300-6869185 Executive Engg Muzafargar Disposed off 11 Arslan Muzzamil Rawalpindi 0312-5641962 Director Colleges Rawalpindi Disposed off 12 Arslan Muzzamil Rawalpindi 0312-5641962 Prin. GGHS Rawalpindi Disposed off 13 Ghulam Hussain UET, Lahore 0300-4533915 UET Lahore Disposed off 14 Muhammad Arshad Muzaffargarr 0302-8941374 TMA Muzaffargarh Disposed off 15 Shahid Aslam Davis Road, Lahore shahidaslam81@gmaiSecretary Fin. Deptt. Lhr Disposed off 16 Muhammad Yonus Dipalpur, Okara 0313-9151351 Princ. DPS, Dipalpur Disposed off 17 Muhammad Afzal Kathi Satellite Town, Jhang 0345-3325269 PIO TMA, Jhang Disposed off 18 Ejaz Nasir Khaniwal 0323-3335332 PIO, Baitul Mall, Khanewal Disposed off 19 Zahid Abdullah Islamabad 051-2375158-9 [email protected] Stat. -

The Naqshbandi-Haqqani Order, Which Has Become Remarkable for Its Spread in the “West” and Its Adaptation to Vernacular Cultures

From madness to eternity Psychiatry and Sufi healing in the postmodern world Athar Ahmed Yawar UCL PhD, Division of Psychiatry 1 D ECLARATION I, Athar Ahmed Yawar, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signed: 2 A BSTRACT Problem: Academic study of religious healing has recognised its symbolic aspects, but has tended to frame practice as ritual, knowledge as belief. In contrast, studies of scientific psychiatry recognise that discipline as grounded in intellectual tradition and naturalistic empiricism. This asymmetry can be addressed if: (a) psychiatry is recognised as a form of “religious healing”; (b) religious healing can be shown to have an intellectual tradition which, although not naturalistic, is grounded in experience. Such an analysis may help to reveal why globalisation has meant the worldwide spread not only of modern scientific medicine, but of religious healing. An especially useful form of religious healing to contrast with scientific medicine is Sufi healing as practised by the Naqshbandi-Haqqani order, which has become remarkable for its spread in the “West” and its adaptation to vernacular cultures. Research questions: (1) How is knowledge generated and transmitted in the Naqshbandi- Haqqani order? (2) How is healing understood and done in the Order? (3) How does the Order find a role in the modern world, and in the West in particular? Methods: Anthropological analysis of psychiatry as religious healing; review of previous studies of Sufi healing and the Naqshbandi-Haqqani order; ethnographic participant observation in the Naqshbandi-Haqqani order, with a special focus on healing. -

List of Trainees of Egp Training

Consultancy Services for “e-GP Related Training” Digitizing Implementation Monitoring and Public Procurement Project (DIMAPPP) Contract Package # CPTU/S-03 Central Procurement Technical Unit (CPTU), IMED Ministry of Planning Training Time Duration: 1st July 2020- 30th June 2021 Summary of Participants # Type of Training No. of Participants 1 Procuring Entity (PE) 876 2 Registered Tenderer (RT) 1593 3 Organization Admin (OA) 59 4 Registered Bank User (RB) 29 Total 2557 Consultancy Services for “e-GP Related Training” Digitizing Implementation Monitoring and Public Procurement Project (DIMAPPP) Contract Package # CPTU/S-03 Central Procurement Technical Unit (CPTU), IMED Ministry of Planning Training Time Duration: 1st July 2020- 30th June 2021 Number of Procuring Entity (PE) Participants: 876 # Name Designation Organization Organization Address 1 Auliullah Sub-Technical Officer National University, Board Board Bazar, Gazipur 2 Md. Mominul Islam Director (ICT) National University Board Bazar, Gazipur 3 Md. Mizanoor Rahman Executive Engineer National University Board Bazar, Gazipur 4 Md. Zillur Rahman Assistant Maintenance Engineer National University Board Bazar, Gazipur 5 Md Rafiqul Islam Sub Assistant Engineer National University Board Bazar, Gazipur 6 Mohammad Noor Hossain System Analyst National University Board Bazar, Gazipur 7 Md. Anisur Rahman Programmer Ministry Of Land Bangladesh Secretariat Dhaka-999 8 Sanjib Kumar Debnath Deputy Director Ministry Of Land Bangladesh Secretariat Dhaka-1000 9 Mohammad Rashedul Alam Joint Director Bangladesh Rural Development Board 5,Kawranbazar, Palli Bhaban, Dhaka-1215 10 Md. Enamul Haque Assistant Director(Construction) Bangladesh Rural Development Board 5,Kawranbazar, Palli Bhaban, Dhaka-1215 11 Nazneen Khanam Deputy Director Bangladesh Rural Development Board 5,Kawranbazar, Palli Bhaban, Dhaka-1215 12 Md.