Coston V. Coston, 25 Md. 500 (Md

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NOMINATION FORM Iiiiliiiii

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) DATA SHEET UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY « NOMINATION FORM iiiiliiiii SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Whfte Hall AND/OR COMMON White Hall LOCATION STREET & NUMBER 4130 Chatham Road —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Ellicott City _X VICINITY OF Sixth STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Maryland 24 Howard 027 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC ^.OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM JfeuiLDiNG(S) ^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL _PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X_PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS X_YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED _YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER. OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Mrs. Harriet Govane Ligon Hains Telephone: 4.6.5-4717 STREET & NUMBER4130 Chatham Road CITY. TOWN Ellicott City VICINITY OF COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC. Howard County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER 8360 Court House Drive CITY, TOWN STATE Ellicott City, Maryland REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE DATE —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY. TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X.ORIGINALSITE —RUINS X.ALTERED —MOVED DATE- —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE White Hall is located on Chatham Road, 1.3 miles south of U.S. Route 40, about 2 miles west of Ellicott City, Howard County, Maryland. The house consists of three sections the east wing, dating from the early 19th century, the center section and the west wing. -

A History of Maryland's Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016

A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 Published by: Maryland State Board of Elections Linda H. Lamone, Administrator Project Coordinator: Jared DeMarinis, Director Division of Candidacy and Campaign Finance Published: October 2016 Table of Contents Preface 5 The Electoral College – Introduction 7 Meeting of February 4, 1789 19 Meeting of December 5, 1792 22 Meeting of December 7, 1796 24 Meeting of December 3, 1800 27 Meeting of December 5, 1804 30 Meeting of December 7, 1808 31 Meeting of December 2, 1812 33 Meeting of December 4, 1816 35 Meeting of December 6, 1820 36 Meeting of December 1, 1824 39 Meeting of December 3, 1828 41 Meeting of December 5, 1832 43 Meeting of December 7, 1836 46 Meeting of December 2, 1840 49 Meeting of December 4, 1844 52 Meeting of December 6, 1848 53 Meeting of December 1, 1852 55 Meeting of December 3, 1856 57 Meeting of December 5, 1860 60 Meeting of December 7, 1864 62 Meeting of December 2, 1868 65 Meeting of December 4, 1872 66 Meeting of December 6, 1876 68 Meeting of December 1, 1880 70 Meeting of December 3, 1884 71 Page | 2 Meeting of January 14, 1889 74 Meeting of January 9, 1893 75 Meeting of January 11, 1897 77 Meeting of January 14, 1901 79 Meeting of January 9, 1905 80 Meeting of January 11, 1909 83 Meeting of January 13, 1913 85 Meeting of January 8, 1917 87 Meeting of January 10, 1921 88 Meeting of January 12, 1925 90 Meeting of January 2, 1929 91 Meeting of January 4, 1933 93 Meeting of December 14, 1936 -

St.John's College

CATALOGUE ~ -OF- St.John's College ANNAPOLIS, MARYLAND -FOR THE- Academic Year, 1915-1916 :::Prospecttts, 1916-1917::: -, ' 1~:.-L... '."'.'. -'::·· c""' ,_• ,~ PRESS OF T:Fllll ADVERTISER-:jtEPUBLICAN ANNAPOµS, MD. UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND. GENERAL STATEME~T. ST. JOHN'S COLLEGE has entered into an affiliation with the Schools of Law, Medicine, Dentistry, and Pharmacy of the University of Maryland. The operation of these working relations is outlined as fol- lows: FIRST. Seniors in St. John's College must do the number of hours required work as specified in the schedule (page 35) for the Senior class. The remaining hours may be supplied by elective studies in the Law School of Maryland University as comprised in that school. Upon the satisfactory completion of this course the degree of Bachelor of Arts or Bachelor of Science is conferred upon such students at the end of the year. The Professional Degree may be reached in two years more. Students so electing must continue their formal reg- istration in the college, though doing part of their work in the Law School. SECOND. Students who have completed the Junior year in St. John's College and who have made an approved choice of electives, may, if they desire it, do the entire work of the Senior year in the Medical School of the University. If they successfully complete the work of the first year in the Medical School they are graduated with their class with the degree of .A. B. or B. S. from St. John's College. By taking advantage of this privilege a man may complete the Undergraduate and Medical courses in seven years. -

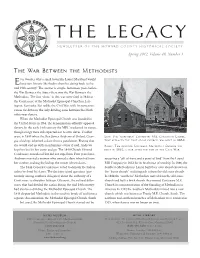

LEGACY Spring 2012, Page 2

THE LEGACY NEWSLETTER OF THE HOWARD COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY Spring 2012, Volume 49, Number 1 The War Between the Methodists ver wonder why a small town like Laurel Maryland would Ehave two historic Methodist churches dating back to the mid 19th century? The answer is simple. Seventeen years before the War Between the States there was the War Between the Methodists. The first “shots” in this war were fired in 1844 at the Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church in Lex- ington, Kentucky. But unlike the Civil War, with its numerous causes for division, the only dividing issue between the Meth- odists was slavery. When the Methodist Episcopal Church was founded in the United States in 1784, the denomination officially opposed slavery. In the early 19th century the MEC weakened its stance, though clergy were still expected not to own slaves. Conflict arose in 1840 when the Rev. James Andrews of Oxford, Geor- Left: the “northern” Centenary M.e. ChurCh in LaureL, gia, a bishop, inherited a slave from a parishioner. Fearing that that repLaCed the first stone ChurCh, was buiLt in 1884. she would end up with an inhumane owner if sold, Andrews right: the originaL southern Methodist ChurCh was kept her but let her come and go. The 1840 Church General buiLt in 1866, a year after the end of the CiviL war. Conference considered but did not expel him. Four years later, Andrews married a woman who owned a slave inherited from accepting a “gift of stone and a grant of land” from the Laurel her mother, making the bishop the owner of two slaves. -

Congr.Ession Al Record- Sen Ate

··.· .. \ ... 1921. CONGR.ESSIONAL RECORD- SENATE. 19 NO:lliNATIONS. NOMINATIONS. FJa:ee1tti1.:e nominations received by the Senate March 9, 1921. Executive nominations received 1Jy the Senate March 10, 1921! To BE AssiS'l'ANT SECRETABIES oF THE TREASURY. CoMPTROLLER OF THE CURRENCY. S. Parker Gilbert, jr., of Bloomfield, N. J., to be Assistant Sec D. R. Crissinger, of Ohio, to be Comptroller of the Om·rency, to retary of the Treasury. fill an existing vacancy. Nicholas Kelley, of New York, N. Y., to be Assistant Secre CoNsULs. tary of the Treasury. The following-named persons for promotion in the Consular Ewing Laporte, of St. Louis, Mo., to be Assistant Secretary of Service of the United States, as follows: the Treasury. CLASS 3. To BE BRIGADIER GENERAL, l\fEDICAL SECTION. Lester :Maynard, of California, from consul of class 4 to con Charles E. Sawyer, from March 7, 1921. sul of class 3. CLASS 4, Willys R. Peck, of California, from consul of class 5 to con· CONFIRMATION. sui of class 4. Executive nomination confirmed by tlle Senate Ma1·ch 9, 1921. CoNsUL oF CLAss 6. To BE ASSISTANT SECRETARY OF THE NAVY. Charles C. Broy, of Virginia, formerly a consul of class 6, Theodore Roosevelt to be Assistant Secretary of the Navy! to be a consul of class 6 of the United States of America. CONFIRM..-\..TIONS. SENATE. Executive norninations con{im~tea by the Senate Ma1·ch 10, 19~1~ ASSIS'J:ANT SECRETARIES OF THE 'J..'REASURY. THURSDAY, March 10, 19~1. S. Pa1·ker Gilbert, jr. Rev. J. -

Year Book of American Clan Gregor Society

YEAR BOOK OF AMERICAN CLAN GREGOR SOCIETY CONTAINING THE PROCEEDINGS AT THE GATHERING OF 1909 AND 1910 YEAR-BOOK OF AMERICAN CLAN GREGOR SOCIETY CONTAINING THE PROCEEDINGS AT THE GATHERINGS OF 1909 AND 1910 Compiled by CALEB CLARKE MAGRUDER, Jr., Historian Members are requested to send notice of change of names and addresses to Dr. Jesse Ewell, Scribe, Ruckersville, Va. The Michie Company, Printers, Charlottesville. Va. 1912 COPYRIGHTED, 1912 BY CALEB CLARKE MAGRUDER, JR. “Resolved, That the Council authorize the publication of the transactions of the Clan and Council to be known as the Year-Book of American Clan Gregor; the first publication to contain the transactions of the years 1909 and 1910; the book to be copyrighted, and sold to members at a cost not to exceed one dollar per volume, and to be of uniform size.” October 27, 1910. THE CALL OF THE CLAN THE AMERICAN BRANCH OF CLAN MACGREGOR. “HONORED AND BLESSED BE THE EVERGREEN PINE.” HEREAS, the history of the Clan MacGregor of Scotland is one in W which the descendants of that Clan should feel just pride; and WHEREAS, there are many descendants of that Clan in America, most of whom are unknown to each other and who would enjoy meeting their brethren and learning more of the Clan history in Scotland and America; THEREFORE it seems advisable to organize Clan MacGregor in this country. To this end, a meeting of MacGregor descendants was held June the 10th, 1909, in Charlottesville, Va., at which a temporary organization called the “American Branch of Clan MacGregor” was formed by the election of Dr. -

Samuel Green: a Black Life in Antebellum Maryland Richard Albert Blondo, Master of Arts, 1988 Thesis D

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: Samuel Green: A Black Life in Antebellum Maryland Richard Albert Blondo, Master of Arts, 1988 Thesis directed by: Dr. David Grimsted, Professor, Department of History, University of Maryland This thesis presents the story of Samuel Green, a free black from Dorchester County, Maryland who was sentenced in 1857 to ten years imprisonment for having in his possession a copy of Uncle Tom's Cabin. Born a slave c. 1802, Green gained his freedom c. 1832 and lived a life of quiet dignity, while enduring the pain of losing his children again to slavery in the late 1840s. Green was respected by both whites and blacks in his community in part because of his status as a local lay minister in the Methodist Episcopal Church. Though suspected of aiding slaves to escape, no evidence was found to convict him of that crime. The planters of Dorchester County eventually succeeded in convicting Green for the crime of possessing the novel, perhaps because of belief in his guilt in aiding slaves escape and certainly because they wanted to believe that some plot must lie behind their "happy" slaves absconding in large numbers. Green bore his fate with some of the Christian fortitude shown by the fictional Uncle Tom. After five years in prison in 1862, Samuel Green was pardoned predicated on his removal to Canada. Through a study of primary documents, including court records, state archival holdings, and newspapers, a touching portrait of an ordinary black who faced extraordinary circumstances unfolds. SAMUEL GREEN: A BLACK LIFE IN ANTEBELLUM MARYLAND by Richard Albert Blondo Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Maryland in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 1988 Advisory Committee: Dr. -

The Baltimore Police Case of 1860, 26 Md

Maryland Law Review Volume 26 | Issue 3 Article 3 The altB imore Police Case of 1860 H. H. Walker Lewis Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr Part of the State and Local Government Law Commons Recommended Citation H. H. Lewis, The Baltimore Police Case of 1860, 26 Md. L. Rev. 215 (1966) Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr/vol26/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Journals at DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maryland Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maryland Law Review VOLUME XXVI SUMMER 1966 NUMBER 3 @ Copyright Maryland Law Review, Inc., 1966 THE BALTIMORE POLICE CASE OF 1860 By H. H. WALKER LEWIS* Recent events have given renewed currency to the hundred year old decision of the Court of Appeals in Baltimore v. State,' upholding the transfer of the Baltimore police to the control of the State. The legislation2 effecting this transfer was adopted February 2, 1860. Its passage occasioned an outcry from City Hall the like of which had not been heard since the days of the Sabine women. But the wails gained no sympathy from the courts. On March 13, 1860, the Act was upheld by the Superior Court of Baltimore City, and on April 17, by the Court of Appeals. No one would quarrel today with the principal holding of the case, that a municipality was legally a creature of the State and that the legislature had power to control its police and other functions. -

Of the Sixty-Sixth Session. Congress

PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE SIXTY-SIXTH CONGRESS THIRD SESSION. SENATE. l\lr. JONES or Washington. Those of the grade of first lieu tenant, commander, and lieutenant commander. They are in FRIDAY, F eb1"Uary 18, 1921. line of promotion in the ordinary way, and not for any definite term, or anything of that kind. (Legislati vc day of Monday, Febn1a1·y 14, 1921.) l\fr. SMOOT. Does it inc!ude the director of the service? The Senate met at 11 o'clock a. m., on the expiration of tlle l\Ir. JOI\TES of Washington. No; no director, or anything recess. of that kind ; they are simply routine promotions. l\Ir. SI\fOOT. Mr. President, I suggest the absence of a Mr. SI\fOOT. I prefer to look over the list, and therefore I quorum. · object at this time. The VICE PRESIDENT. The Secretary will call the roll. THE PA.TE::.'\'T OFFICE-CONFERENCE REPORT. The reading clerk called the roll, and the following Senators l\Ir. NOHRIS. Mr. President, yesterday I asked unanimous amnvered to their names : consent to fix a time for voting on the conference report on llall Gooding McLr an Spencer the disagreeing votes of the two Houses on the amendments of Calder Harris McNary Sutherland the Senate to the bill (II. 11984) to increase the force and Capper Harrison Moses Swanson n. Cha mberlain Heflin New Thomas salaries ·in the Patent Office, and for other purposes. Objec Colt Hender8on Norris Townsend tion '"as then made because of the absence from the Senate of Culberson Jones, N.Mex. -

Emerson C. Harrington, Thomas W. Simmons

EMERSON C. HARRINGTON, THOMAS W. SIMMONS, 392206 MARYLAND MANUAL 19i 7-i 9i 8 A Compendium of Legal, Historical and Statistical Information relating to the STATE OF MARYLAND COMPILED BY THE SECRETARY OF STATE ■ PBJD8S 01*... MM Advsbtissb- Rxptjblic a k ANNAPOLIS, - - HD. CHARTER OF MARYLAND TRANSLATED EROM THE LATIN ORIGINAL CHARLES,* by the grace of GOD, of England, Scotland, France, and Ireland, king, Defender of the Faith, &c. To all to whom these Presents shall come, Greeting. II. Whereas our well beloved and right trusty Subject, CiECILIUS CALVERT, Baron of BALTIMORE, in our Kingdom of Ireland, Son and Heir of GEORGE CALVERT, Knight, late Baron of BALTIMORE, in our said Kingdom of Ireland, treading in the Steps of his Father, being ani- mated with a laudable and pious Zeal for extending the' Christian Religion, and also the Territories of our Empire, hath humbly besought leave of Us, that he may transport by his own Industry, and Expence, a numerous Colony of the English Nation, to a certain Region, herein after described, in a Country hitherto uncultivated, in the parts of America and partly occupied by Savages, having no Knowledge of the Divine Being, and that all that Region, with some certain Privileges, and Jurisdiction, appertaining unto the whole- some Government, and State of his Colony and Region afore- said may by our Royal Highness be given, granted, and con- firmed unto him and his heirs. III. Know te therefore that WE, encouraging with our Royal Favour, the pious and noble Purpose of the aforesaid Baron of BALTIMORE, -

FRAZER AXLE Nye's Practical Joke, 1777, Thomas Johnson

unlit but mktt W. H. TROXELL, Editor & Publisher. Established by SAMUEL MOTTER in 1879. TERMS-V.00 a Year in Advance. VOL. XVII. EMMITSBURG, MARYLAND, FRIDAY, JANUARY 17, 1890 NO. 34, DIRECTORY AVE ATQUE _ VALE. 1815, Charles Ridgely, of Hamp- The Underground Railway. buried S. beneath London. It cost, FOR FREDERICK COUNTY You that have gone before me, ton. d One great object, though I do at least, New York's To the dark unknown, elevated rail- Circuit Court. 1818, Charles Goldsborough. not believe it had occurred to Mr. way has MeSherry. One by one who have left me the advantege; its £81,376 Chief Judge-lion.James DEMOCRATS. Pearson himself, was to make the Associate Judges-lion. John A. Lynch and To walk alone. a mile seems by comparison modest lion. James B. Henderson, 1819, Samuel Sprigg. road pass as close State's Attorney- Wtn. Ii. 'links. What is as possible to the and insignficant.-Harpee'e L. Jordan. Friends of my Alaga- Clerk of the Court-John youth and manhood 1822, Samuel Stevens, Jr. great railway stations of London, zine. Court. ',\SdNN:N ‘'S .\\\NRON Vanished away, Orphan's .\\'‘ N.')• 1825, Joseph Kent. and then along the north side of -John W. Crinder, Wm. If. Young and ' Like a drift of crimson sunset Judges ANTI A henry B. Wilson. At -JACKSON. the Thames, so as to complete the Desperado's Death. Register of Wills-James K. Waters. close of day ! 1828, Daniel Martin. circle-an object eventually ac- J. K. Chambers, Union Depot County Officer-A. We held sweet converse together -William N. -

Mdsa Sc1198 2 20.Pdf

J-*r/3r/i 802302 ■% ■ i >4 l GOVERNOR-ELECT EMERSON C. HARRINGTON. GOVERNOR PHILLIPS LEE GOLDSBOROUGH. Term expires second Wednesday in January, 19£0. Term expires January 12 1916. MARYLAND MANUAL 1915-1916 A Compendium of Legal, Historical and Statistical Information relating to the STATE OF MARYLAND COMPILED BY THE SECRETARY OF STATE P2USSS OF THB ADVBBTISBB-BBPUBLICANj ANNAPOLIS, MD. CHARTER OF MARYLAND TRANSLATED FROM THE LATIN ORIGINAL CHARLES,* by the grace of GOD, of England, Scotland, France, and Ireland, king, Defender of the Faith, &c. To all to whom these Presents shall come, Greeting. II. Whereas our well beloved and right trusty Subject, CiECILIUS CALVERT, Baron of BALTIMORE, in our Kingdom of Ireland, Son and Heir of GEORGE CALVERT, Knight, late Baron of BALTIMORE, in our said Kingdom of Ireland, treading in the Steps of his Father, being ani- mated with a laudable and pious Zeal for extending the Christian Religion, and also the Territories of our Empire, hath humbly besought leave of Us, that he may transport by his own Industry, and Expence, a numerous Colony of the English Nation, to a certain Region, herein after described, in a Country hitherto uncultivated, in the parts of America and partly occupied by Savages, having no Knowledge of the Divine Being, and that all that Region, with some certain Privileges, and Jurisdiction, appertaining unto the whole- some Government, and State of his Colony and Region afore- said may by our Royal Highness be given, granted, and con- firmed unto him and his heirs. III. Know ye therefore