A Case for the Encoding of Psychedelically Induced Spirituality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hindu America

HINDU AMERICA Revealing the story of the romance of the Surya Vanshi Hindus and depicting the imprints of Hindu Culture on tho two Americas Flower in the crannied wall, I pluck you out of the crannies, I hold you here, root and all, in my hand. Little flower— but if I could understand What you arc. root and all. and all in all, I should know what God and man is — /'rimtjihui' •lis far m the deeps of history The Voice that speaVeth clear. — KiHtf *Wf. The IIV./-SM#/. CHAMAN LAL NEW BOOK CO HORNBY ROAD, BOMBAY COPY RIGHT 1940 By The Same Author— SECRETS OF JAPAN (Three Editions in English and Six translations). VANISHING EMPIRE BEHIND THE GUNS The Daughters of India Those Goddesses of Piety and Sweetness Whose Selflessness and Devotion Have Preserved Hindu Culture Through the Ages. "O Thou, thy race's joy and pride, Heroic mother, noblest guide. ( Fond prophetess of coming good, roused my timid mood.’’ How thou hast |! THANKS My cordial chaoks are due to the authors and the publisher* mentioned in the (eat for (he reproduction of important authorities from their books and loumils. My indchtcdih-ss to those scholars and archaeologists—American, European and Indian—whose works I have consulted and drawn freely from, ts immense. Bur for the results of list investigations made by them in their respective spheres, it would have been quite impossible for me to collect materials for this book. I feel it my duty to rhank the Republican Governments of Ireland and Mexico, as also two other Governments of Europe and Asia, who enabled me to travel without a passport, which was ruthlessly taken away from me in England and still rests in the archives of the British Foreign Office, as a punishment for publication of my book the "Vanishing Empire!" I am specially thankful to the President of the Republic of Mexico (than whom there is no greater democrat today)* and his Foreign Minister, Sgr. -

Hanuman Chalisa.Pdf

Shree Hanuman Chaleesa a sacred thread adorns your shoulder. Gate of Sweet Nectar 6. Shankara suwana Kesaree nandana, Teja prataapa mahaa jaga bandana Shree Guru charana saroja raja nija You are an incarnation of Shiva and manu mukuru sudhari Kesari's son/ Taking the dust of my Guru's lotus feet to Your glory is revered throughout the world. polish the mirror of my heart 7. Bidyaawaana gunee ati chaatura, Baranaun Raghubara bimala jasu jo Raama kaaja karibe ko aatura daayaku phala chaari You are the wisest of the wise, virtuous and I sing the pure fame of the best of Raghus, very clever/ which bestows the four fruits of life. ever eager to do Ram's work Buddhi heena tanu jaanike sumiraun 8. Prabhu charitra sunibe ko rasiyaa, pawana kumaara Raama Lakhana Seetaa mana basiyaa I don’t know anything, so I remember you, You delight in hearing of the Lord's deeds/ Son of the Wind Ram, Lakshman and Sita dwell in your heart. Bala budhi vidyaa dehu mohin harahu kalesa bikaara 9. Sookshma roopa dhari Siyahin Grant me strength, intelligence and dikhaawaa, wisdom and remove my impurities and Bikata roopa dhari Lankaa jaraawaa sorrows Assuming a tiny form you appeared to Sita/ in an awesome form you burned Lanka. 1. Jaya Hanumaan gyaana guna saagara, Jaya Kapeesha tihun loka ujaagara 10. Bheema roopa dhari asura sanghaare, Hail Hanuman, ocean of wisdom/ Raamachandra ke kaaja sanvaare Hail Monkey Lord! You light up the three Taking a dreadful form you slaughtered worlds. the demons/ completing Lord Ram's work. -

Bhagavad Gita Chapter 10: Divine Emanations

Bhagavad Gita Chapter 10: Divine Emanations Tonight we will be doing chapter 10 of the Bhagavad Gita, Vibhuti Yoga, The Yoga of Divine Emanations. But first I want to talk about the nature of the journey. For most of us Westerners this aspect of the Gita is not available to us. Very few people in the West open up to God, to the collective consciousness, in the experiential way that is being revealed here. Most spiritual teachings have more to do with the development of the psychic intelligence and its relationship to truth. Vibhuti Yoga is truly devotional. A vast majority of people have a devotional relationship or feeling for whatever God or Allah or Zoroaster represents. It comes from something in our human nature that is transferring onto an idea, from the human collective consciousness, and is different from what we will be talking about today. (2:00) Vibhuti Yoga is a direct revelation from the universe to the individual. What we might call devotion is absolutely felt, but of a completely different order than what we would call religious devotion or the fervor that occurs with born again Christians or with people that are motivated from their vital for this passionate relationship, for this idea of God. That comes from the higher heart, the higher vital, the part of our human nature that is rising up from our focus on our relationships and attachments and identifications associated with community and society. It is a part of us that lifts to a possibility. It is to some extent associated with what I call the psychic heart. -

South-Indian Images of Gods and Goddesses

ASIA II MB- • ! 00/ CORNELL UNIVERSITY* LIBRARY Date Due >Sf{JviVre > -&h—2 RftPP )9 -Af v^r- tjy J A j£ **'lr *7 i !! in ^_ fc-£r Pg&diJBii'* Cornell University Library NB 1001.K92 South-indian images of gods and goddesse 3 1924 022 943 447 AGENTS FOR THE SALE OF MADRAS GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. IN INDIA. A. G. Barraud & Co. (Late A. J. Combridge & Co.)> Madras. R. Cambrav & Co., Calcutta. E. M. Gopalakrishna Kone, Pudumantapam, Madura. Higginbothams (Ltd.), Mount Road, Madras. V. Kalyanarama Iyer & Co., Esplanade, Madras. G. C. Loganatham Brothers, Madras. S. Murthv & Co., Madras. G. A. Natesan & Co., Madras. The Superintendent, Nazair Kanun Hind Press, Allahabad. P. R. Rama Iyer & Co., Madras. D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., Bombay. Thacker & Co. (Ltd.), Bombay. Thacker, Spink & Co., Calcutta. S. Vas & Co., Madras. S.P.C.K. Press, Madras. IN THE UNITED KINGDOM. B. H. Blackwell, 50 and 51, Broad Street, Oxford. Constable & Co., 10, Orange Street, Leicester Square, London, W.C. Deighton, Bell & Co. (Ltd.), Cambridge. \ T. Fisher Unwin (Ltd.), j, Adelphi Terrace, London, W.C. Grindlay & Co., 54, Parliament Street, London, S.W. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. (Ltd.), 68—74, iCarter Lane, London, E.C. and 25, Museum Street, London, W.C. Henry S. King & Co., 65, Cornhill, London, E.C. X P. S. King & Son, 2 and 4, Great Smith Street, Westminster, London, S.W.- Luzac & Co., 46, Great Russell Street, London, W.C. B. Quaritch, 11, Grafton Street, New Bond Street, London, W. W. Thacker & Co.^f*Cre<d Lane, London, E.O? *' Oliver and Boyd, Tweeddale Court, Edinburgh. -

Ancient Wisdom, Modern Life Mount Soma Timeline

Mount Soma Ancient Wisdom, Modern Life Mount Soma Timeline Dr. Michael Mamas came across the information about building an Enlightened City. 1985 Over time, it turned into his Dharmic purpose. November, 2002 The founders of Mount Soma came forth to purchase land. May, 2003 Began cutting in the first road at Mount Soma, Mount Soma Blvd. January, 2005 The first lot at Mount Soma was purchased. May, 2005 First paving of Mount Soma’s main roads. April, 2006 Dr. Michael Mamas had the idea of a Shiva temple at Mount Soma. Marcia and Lyle Bowes stepped forward with the necessary funding to build Sri October, 2006 Somesvara Temple. January, 2007 Received grant approval from Germeshausen Foundation to build the Visitor Center. July, 2007 Received first set of American drawings for Sri Somesvara Temple from the architects. Under the direction of Sthapati S. Santhanakrishnan, a student and relative of Dr. V. July, 2007 Ganapati Sthapati, artisans in India started carving granite for Sri Somesvara Temple. October, 2007 First house finished and occupied at Mount Soma. January, 2008 Groundbreaking for Visitor Center. May, 2008 146 crates (46 tons) of hand-carved granite received from India at Mount Soma. July, 2008 Mount Soma inauguration on Guru Purnima. July/August, 2008 First meditation retreat and class was held at the Visitor Center. February, 2009 Mount Soma Ashram Program began. July, 2009 Started construction of Sri Somesvara Temple. January, 2010 Received grant approval from Germeshausen Foundation to build the Student Union. August, 2010 American construction of Sri Somesvara Temple completed. Sthapati and shilpis arrived to install granite and add Vedic decorative design to Sri October, 2010 Somesvara Temple. -

Thai Words Produced by Ianthe Cormack Thai English Gender Description Pronounciation

Thai Words Produced by Ianthe Cormack Thai English Gender Description Pronounciation Ah-ngoon Grape Fruit Ah-ngun Grape Vine Flower Ah-roy Delicious [food] Amp-har Amber Gem Stone Ampa Lady Female Ampa Mother Female Ananda Prosperous Male Anurak Male Angel Male Apasra Adorn Female Apsara Angel Female Apsara Angelic Female Aram Bright & Beautiful Male Aree Generous Female Aree Helpful Arkorn Arrival Male Arom Emotion Female Aroon Morning Male Artorn Generosity Male Arun Dawn Asa Hope Male Asvin Horse Soldier Male Aswin Asvin Knight Male Aswin Awn-wahn Sweet [disposition] Bal Hora-pah Sweet Basil Herb/Spice Bal Sara-nea Mint Herb/Spice Ban-mai Ru-roey Batchelors Buttons Flower Ban-yen Marvel of Peru Flower Banem Unexpected Banghuen Zinnia Flower Bao-bao Gentle Baw-ri-soot Innocent[pure] Bong-khaam A lucky stone Gem Stones Boo Chan Witness Boon Good Deeds Male Boon* Goodness Male Boon* Merit Male Boon-nam Good fortune Boon-nam Sent by God Boong Furry Caterpillar Animals Boonmii Good Deeds[to have] Bpah-teuun Wild Bpet Duck Animals Bua Night-blooming Water Lily Flower Bua Luang Lotus Flower Buddha Chart Jasmine Flower Buddha Rak-sa Canna Lily Flower Busaba Female Flower But Sara-Ktam Yellow Sapphire Gem Stones 1 Thai Words Produced by Ianthe Cormack Thai English Gender Description Pronounciation Cha Singapore Holly Flower Cha-ba Hibiscus Flower Cha-ya Pruk Yellow Cassia Tree Chahng Elephant Animals Chalerm Celebrated Male Chalermchai Celebrated Victory Male Chalermwan Celebrated Beauty Female Chaluay Graceful Cham Chu-ree Rain Tree Tree Cham-ma-Nart -

Vedic Brahmanism and Its Offshoots

Vedic Brahmanism and Its Offshoots Buddhism (Buddha) Followed by Hindūism (Kṛṣṇā) The religion of the Vedic period (also known as Vedism or Vedic Brahmanism or, in a context of Indian antiquity, simply Brahmanism[1]) is a historical predecessor of Hinduism.[2] Its liturgy is reflected in the Mantra portion of the four Vedas, which are compiled in Sanskrit. The religious practices centered on a clergy administering rites that often involved sacrifices. This mode of worship is largely unchanged today within Hinduism; however, only a small fraction of conservative Shrautins continue the tradition of oral recitation of hymns learned solely through the oral tradition. Texts dating to the Vedic period, composed in Vedic Sanskrit, are mainly the four Vedic Samhitas, but the Brahmanas, Aranyakas and some of the older Upanishads (Bṛhadāraṇyaka, Chāndogya, Jaiminiya Upanishad Brahmana) are also placed in this period. The Vedas record the liturgy connected with the rituals and sacrifices performed by the 16 or 17 shrauta priests and the purohitas. According to traditional views, the hymns of the Rigveda and other Vedic hymns were divinely revealed to the rishis, who were considered to be seers or "hearers" (shruti means "what is heard") of the Veda, rather than "authors". In addition the Vedas are said to be "apaurashaya", a Sanskrit word meaning uncreated by man and which further reveals their eternal non-changing status. The mode of worship was worship of the elements like fire and rivers, worship of heroic gods like Indra, chanting of hymns and performance of sacrifices. The priests performed the solemn rituals for the noblemen (Kshsatriya) and some wealthy Vaishyas. -

Vishvarupadarsana Yoga (Vision of the Divine Cosmic Form)

Vishvarupadarsana Yoga (Vision of the Divine Cosmic form) 55 Verses Index S. No. Title Page No. 1. Introduction 1 2. Verse 1 5 3. Verse 2 15 4. Verse 3 19 5. Verse 4 22 6. Verse 6 28 7. Verse 7 31 8. Verse 8 33 9. Verse 9 34 10. Verse 10 36 11. Verse 11 40 12. Verse 12 42 13. Verse 13 43 14. Verse 14 45 15. Verse 15 47 16. Verse 16 50 17. Verse 17 53 18. Verse 18 58 19. Verse 19 68 S. No. Title Page No. 20. Verse 20 72 21. Verse 21 79 22. Verse 22 81 23. Verse 23 84 24. Verse 24 87 25. Verse 25 89 26. Verse 26 93 27. Verse 27 95 28. Verse 28 & 29 97 29. Verse 30 102 30. Verse 31 106 31. Verse 32 112 32. Verse 33 116 33. Verse 34 120 34. Verse 35 125 35. Verse 36 132 36. Verse 37 139 37. Verse 38 147 38. Verse 39 154 39. Verse 40 157 S. No. Title Page No. 40. Verse 41 161 41. Verse 42 168 42. Verse 43 175 43. Verse 44 184 44. Verse 45 187 45. Verse 46 190 46. Verse 47 192 47. Verse 48 196 48. Verse 49 200 49. Verse 50 204 50. Verse 51 206 51. Verse 52 208 52. Verse 53 210 53. Verse 54 212 54. Verse 55 216 CHAPTER - 11 Introduction : - All Vibhutis in form of Manifestations / Glories in world enumerated in Chapter 10. Previous Description : - Each object in creation taken up and Bagawan said, I am essence of that object means, Bagawan is in each of them… Bagawan is in everything. -

Akshaya Tritiya Special Puja

Hindu Temple & Cultural Center of WI American Hindu Association 2138 South Fish Hatchery Road, Fitchburg, WI 53575 AHA Shiva Vishnu Temple Akshaya Tritiya Special Puja & Lalitha Sahasranamam Recital May 2, 2014 ~ Friday-6:30pm to 8pm Goddess Maha Lakshmi & Lord Kubera Abishekam & Puja SPONSORSHIP: $108 for the 1g Laxmi* gold coin Puja conducted by Priest Madhavan Bhattar Venue: 2138 South Fish Hatchery Rd, Fitchburg, WI 53575 Prasad will be served at the temple Akshaya Trithiya : Akshaya (meaning Never-Ending, or that which never diminishes) Trithiya (the Third Day of Shuklapaksha(Waxing Moon)) in the Vishaka Month is regarded as the day of eternal success. The Sun and Moon are both in exalted position, or simultaneous at their peak of brightness, on this day, which occurs only once every year. This day is widely celebrated as Parusurama Jayanthi, in honor of Parusurama – the sixth incarnation of Lord Maha Vishnu. Lord Kubera, who is the keeper of wealth for Goddess Maha Lakshmi, is said to himself pray to the Goddess on this day. Lord maha Vishnu and his Avatars, Goddess Maha Lakshmi and Lord Kubera are worshipped on Akshaya Trithiya Day. Veda vyasa began composing Mahabharatha on this day. Since Divine Mother Goddess Maha Lakshmi is intensely and actively manifest and due to the mystical nature of our Temple, all Pirthurs(all our ancestors’ subtle and causal bodies) congregate at our Temple. All these Ethereal beings are pleased and will gain higher cosmic energy when we offer pujas on their behalf. Pitru Tarpanam can be done on any day of the year depending on the day one’s ancestors passed away, but performing it during Mahalaya Amavasya and Akshaya Trithiya will multifold benefits. -

India's "Tīrthas": "Crossings" in Sacred Geography

India's "Tīrthas": "Crossings" in Sacred Geography The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Eck, Diana L. 1981. India's "Tīrthas": "Crossings" in sacred geography. History of Religions 20 (4): 323-344. Published Version http://www.jstor.org/stable/1062459 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:25499831 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA DianaL.Eck INDIA'S TIRTHAS: "CROSSINGS" IN SACRED GEOGRAPHY One of the oldest strands of the Hindu tradition is what one might call the "locative" strand of Hindu piety. Its traditions of ritual and reverence are linked primarily to place-to hill- tops and rock outcroppings, to the headwaters and confluences of rivers, to the pools and groves of the forests, and to the boundaries of towns and villages. In this locative form of religiousness, the place itself is the primary locus of devotion, and its traditions of ritual and pilgrimage are usually much older than any of the particular myths and deities which attach to it. In the wider Hindu tradition, these places, par- ticularly those associated with waters, are often called tirthas, and pilgrimage to these tirthas is one of the oldest and still one of the most prominent features of Indian religious life. A tZrtha is a "crossing place," a "ford," where one may cross over to the far shore of a river or to the far shore of the worlds of heaven. -

A Compact Biography of Shri Vasudevanand Saraswati (Tembe) Swami

**¸ÉÒMÉÖ¯û& ¶É®úhɨÉÂ** A compact biography of Shri Vasudevanand Saraswati (Tembe) Swami. First Edition: June 2006. A compact biography Publishers: of Shashwat Prakashan Shri Vasudevanand Saraswati 206, Amrut Cottage, near Diwanman Sai Temple (Tembe) Sw āmi. Manikpur VASAI ROAD (W) Dist. Thane 401202 Phone: 0250-2343663. Copyright: Dr. Vasudeo V. Deshmukh, Pune By Compose: Dr. Vasudeo V. Deshmukh. www.shrivasudevanandsaraswati.com Printers: Shri Dilipbhai Panchal SUPR FINE ART, Mumbai. Phone 022-24944259. Price: Rs. 250.00 Publishers Shashwat Prakashan, Vasai. This book is sponsored by P.P. Shri Vasudevanand Saraswati (Tembe) Swami Maharaj Prabodhini. ii Dedicated to the Sacred Memory of My Master ā ā ā The picture of Shri Sw mi Mah r ja on the cover page displays the lyrical garland (H ārabandha) composed by P.P. Shri Dixita Sw āmi in his praise. ˜Ìâ¨ÌÉ Fâò¨ÌÉ ²ÌÙ¨ÌÉ—ÌÙÉ —ÌÙ¥ÌÌ¥Ì̷̥Éþ ˜ÌÌœú·Éþ œúvÌœúvÌÉ* ¥ÌÉzâù ¬ÌÕzâù¥Ìzâù¥ÌÉ ²ÌOÌÙsÌOÌÙûœúOÌÙÉû ¬ÌÕFòœÉú FÉò`ÌFÉò`ÌÉ** M®¿aÆ K®¿aÆ Su¿ambhuÆ BhuvanavanavahaÆ M¡rahaÆ RatnaratnaÆ. Vand® ár¢d®vad®vaÆ Sagu¸agururaguruÆ ár¢karaÆ KaµjakaµjaÆ.. Yogir āja Vja V āmanrao D. Gu½ava¸¢ Mah¡r¡ja iii iv The scheme of transliteration. Blessings of P. Pujya Shri Narayan Kaka Maharaj Dhekane. + +Ì < <Ê = >ð @ñ Añ ीगणेशदतगु यो नमः। Paramahans Parivr ājak āch ārya Shri V āsudevananda a ¡ i ¢ u £ ¤ ¥ Saraswati (Tembe) Swami Maharaj is widely believed to be the incarnation of Lord Datt ātreya. In his rather brief life of 60 years, 24 of D Dâ +Ìâ +Ìæ +É +: them as an itinerant monk, he revived not only the Datta tradition but also the Vedic religion as expounded in the Smritis and Pur ānās. -

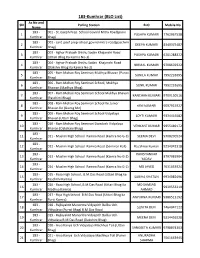

183-Kumhrar (BLO List) Ac No and Sl# Polling Station BLO Mobile No Name 183 - 001 - St Joseph Prep

183-Kumhrar (BLO List) Ac No and Sl# Polling Station BLO Mobile No Name 183 - 001 - St Joseph Prep. School Govind Mitra Road(purvi 1 PUSHPA KUMARI 7762067538 Kumhrar bhag) 183 - 002 - sant josef prep school,govind mitra road(paschimi 2 DEEPA KUMARI 8340375487 Kumhrar bhag) 183 - 003 - Aghor Prakash Shishu Sadan Khajanchi Road 3 PUSHPA KUMARI 6201288322 Kumhrar (Uttari Bhag Ka Kamra No-3) 183 - 004 - Aghor Prakash Shishu Sadan Khajanchi Road 4 NIRMAL KUMARI 9708602922 Kumhrar (Dakshni Bhag Ka Kamra No-2) 183 - 005 - Ram Mohan Roy Seminari Mukhya Bhavan (Purwi 5 SUNILA KUMAR 7992231695 Kumhrar Bhag) 183 - 006 - Ram Mohan Roy Seminari School, Mukhya 6 SUNIL KUMAR 7992231695 Kumhrar Bhawan (Madhya Bhag) 183 - 007 - Ram Mohan Roy Seminari School Mukhya Bhavan 7 KANCHAN KUMARI 9709150516 Kumhrar (Paschimi Bhag) 183 - 008 - Ram Mohan Roy Seminari School Ke Junior 8 rANI kUMARI 9097915927 Kumhrar Bhavan Ke (Gairag Me) 183 - 009 - Ram Mohan Roy Seminari School Vidyalaya 9 JOYTI KUMARI 9334416582 Kumhrar Bhavan (Uttari Bhag) 183 - 010 - Ram Mohan Roy Seminari Dwadash Vidyalaya 10 VENKANT KUMAR 9955489172 Kumhrar Bhavan (Dakshani Bhag) 183 - 11 011 - Muslim High School Ramna Road (Kamra No G-3) SEEMA DEVI 9708200524 Kumhrar 183 - 12 012 - Muslim High School Ramna Road (Seminar Hall) Raj Shree Kumari 9234342318 Kumhrar 183 - RAVISHANKAR 13 013 - Muslim High School Ramna Road (Kamra No G-2) 8797983904 Kumhrar YADAV 183 - 14 014 - Muslim High School Ramna Road (Kamra No G-1) MD JAVED 7631653924 Kumhrar 183 - 015 - Raza High School , B.M.Das Road (Uttari