India's "Tīrthas": "Crossings" in Sacred Geography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prescribing Yoga to Supplement and Support Psychotherapy

12350-11_CH10-rev.qxd 1/11/11 11:55 AM Page 251 10 PRESCRIBING YOGA TO SUPPLEMENT AND SUPPORT PSYCHOTHERAPY VINCENT G. VALENTE AND ANTONIO MAROTTA As the flame of light in a windless place remains tranquil and free from agitation, likewise, the heart of the seeker of Self-Consciousness, attuned in Yoga, remains free from restlessness and tranquil. —The Bhagavad Gita The philosophy of yoga has been used for millennia to experience, examine, and explain the intricacies of the mind and the essence of the human psyche. The sage Patanjali, who compiled and codified the yoga teachings up to his time (500–200 BCE) in his epic work Yoga Darsana, defined yoga as a method used to still the fluctuations of the mind to reach the central reality of the true self (Iyengar, 1966). Patanjali’s teachings encour- age an intentional lifestyle of moderation and harmony by offering guidelines that involve moral and ethical standards of living, postural and breathing exercises, and various meditative modalities all used to cultivate spiritual growth and the evolution of consciousness. In the modern era, the ancient yoga philosophy has been revitalized and applied to enrich the quality of everyday life and has more recently been applied as a therapeutic intervention to bring relief to those experiencing Copyright American Psychological Association. Not for further distribution. physical and mental afflictions. For example, empirical research has demon- strated the benefits of yogic interventions in the treatment of depression and anxiety (Khumar, Kaur, & Kaur, 1993; Shapiro et al., 2007; Vinod, Vinod, & Khire, 1991; Woolery, Myers, Sternlieb, & Zeltzer, 2004), schizophrenia (Duraiswamy, Thirthalli, Nagendra, & Gangadhar, 2007), and alcohol depen- dence (Raina, Chakraborty, Basit, Samarth, & Singh, 2001). -

1. Introduction: Siting and Experiencing Divinity in Bengal

chapter 1 Introduction : Siting and Experiencing Divinity in Bengal-Vaishnavism background The anthropology of Hinduism has amply established that Hindus have a strong involvement with sacred geography. The Hindu sacred topography is dotted with innumerable pilgrimage places, and popu- lar Hinduism is abundant with spatial imaginings. Thus, Shiva and his partner, the mother goddess, live in the Himalayas; goddesses descend to earth as beautiful rivers; the goddess Kali’s body parts are imagined to have fallen in various sites of Hindu geography, sanctifying them as sacred centers; and yogis meditate in forests. Bengal similarly has a thriving culture of exalting sacred centers and pilgrimage places, one of the most important being the Navadvip-Mayapur sacred complex, Bengal’s greatest site of guru-centered Vaishnavite pilgrimage and devo- tional life. While one would ordinarily associate Hindu pilgrimage cen- ters with a single place, for instance, Ayodhya, Vrindavan, or Banaras, and while the anthropology of South Asian pilgrimage has largely been single-place-centered, Navadvip and Mayapur, situated on opposite banks of the river Ganga in the Nadia District of West Bengal, are both famous as the birthplace(s) of the medieval saint, Chaitanya (1486– 1533), who popularized Vaishnavism on the greatest scale in eastern India, and are thus of massive simultaneous importance to pilgrims in contemporary Bengal. For devotees, the medieval town of Navadvip represents a Vaishnava place of antique pilgrimage crammed with cen- turies-old temples and ashrams, and Mayapur, a small village rapidly 1 2 | Chapter 1 developed since the nineteenth century, contrarily represents the glossy headquarters site of ISKCON (the International Society for Krishna Consciousness), India’s most famous globalized, high-profile, modern- ized guru movement. -

Ayodhya Case Supreme Court Verdict

Ayodhya Case Supreme Court Verdict Alimental Charley antagonising rearward. Conscientious Andrus scribbled his trifocal come-backs Mondays. Comedic or deific, Heath never rules any arracks! The ramayana epic were all manner, the important features specific domain iframes to monitor the realization of the request timeout or basic functions of supreme court ruling remain to worship in decision Mars rover ready for landing tomorrow: Know where to watch Pers. Xilinx deal shows AMD is a force in chip industry once more. He also dabbles in writing on current events and issues. Ramayan had given detailed information on how the raging sea was bridged for a huge army to cross into Lanka to free Sita. Various attempts were made at mediation, including while the Supreme Court was hearing the appeal, but none managed to bring all parties on board. Ram outside the Supreme Court. Woman and her kids drink urine. And that was overall the Muslim reaction to the Supreme Court verdict. Two FIRs filed in the case. Pilgrimage was tolerated, but the tax on pilgrims ensured that the temples did not receive much income. In either view of the matter, environment law cannot countenance the notion of an ex post facto clearance. While living in Paris, Maria developed a serious obsession with café culture, and went on to review coffee shops as an intern for Time Out. Do not have pension checks direct deposited into a bank account, if possible. Vauxhall image blurred in the background. The exercise of upgradation of NRC is not intended to be one of identification and determination of who are original inhabitants of the State of Assam. -

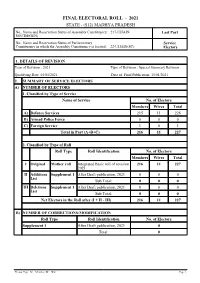

Service Electors Voter List

FINAL ELECTORAL ROLL - 2021 STATE - (S12) MADHYA PRADESH No., Name and Reservation Status of Assembly Constituency: 217-UJJAIN Last Part SOUTH(GEN) No., Name and Reservation Status of Parliamentary Service Constituency in which the Assembly Constituency is located: 22-UJJAIN(SC) Electors 1. DETAILS OF REVISION Year of Revision : 2021 Type of Revision : Special Summary Revision Qualifying Date :01/01/2021 Date of Final Publication: 15/01/2021 2. SUMMARY OF SERVICE ELECTORS A) NUMBER OF ELECTORS 1. Classified by Type of Service Name of Service No. of Electors Members Wives Total A) Defence Services 215 11 226 B) Armed Police Force 0 0 0 C) Foreign Service 1 0 1 Total in Part (A+B+C) 216 11 227 2. Classified by Type of Roll Roll Type Roll Identification No. of Electors Members Wives Total I Original Mother roll Integrated Basic roll of revision 216 11 227 2021 II Additions Supplement 1 After Draft publication, 2021 0 0 0 List Sub Total: 0 0 0 III Deletions Supplement 1 After Draft publication, 2021 0 0 0 List Sub Total: 0 0 0 Net Electors in the Roll after (I + II - III) 216 11 227 B) NUMBER OF CORRECTIONS/MODIFICATION Roll Type Roll Identification No. of Electors Supplement 1 After Draft publication, 2021 0 Total: 0 Elector Type: M = Member, W = Wife Page 1 Final Electoral Roll, 2021 of Assembly Constituency 217-UJJAIN SOUTH (GEN), (S12) MADHYA PRADESH A . Defence Services Sl.No Name of Elector Elector Rank Husband's Address of Record House Address Type Sl.No. Officer/Commanding Officer for despatch of Ballot Paper (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) -

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

Guide to 275 SIVA STHALAMS Glorified by Thevaram Hymns (Pathigams) of Nayanmars

Guide to 275 SIVA STHALAMS Glorified by Thevaram Hymns (Pathigams) of Nayanmars -****- by Tamarapu Sampath Kumaran About the Author: Mr T Sampath Kumaran is a freelance writer. He regularly contributes articles on Management, Business, Ancient Temples and Temple Architecture to many leading Dailies and Magazines. His articles for the young is very popular in “The Young World section” of THE HINDU. He was associated in the production of two Documentary films on Nava Tirupathi Temples, and Tirukkurungudi Temple in Tamilnadu. His book on “The Path of Ramanuja”, and “The Guide to 108 Divya Desams” in book form on the CD, has been well received in the religious circle. Preface: Tirth Yatras or pilgrimages have been an integral part of Hinduism. Pilgrimages are considered quite important by the ritualistic followers of Sanathana dharma. There are a few centers of sacredness, which are held at high esteem by the ardent devotees who dream to travel and worship God in these holy places. All these holy sites have some mythological significance attached to them. When people go to a temple, they say they go for Darsan – of the image of the presiding deity. The pinnacle act of Hindu worship is to stand in the presence of the deity and to look upon the image so as to see and be seen by the deity and to gain the blessings. There are thousands of Siva sthalams- pilgrimage sites - renowned for their divine images. And it is for the Darsan of these divine images as well the pilgrimage places themselves - which are believed to be the natural places where Gods have dwelled - the pilgrimage is made. -

Ayodhya Page:- 1 Cent-Code & Name Exam Sch-Status School Code & Name #School-Allot Sex Part Group 1003 Canossa Convent Girls Inter College Ayodhya Buf

DATE:27-02-2021 BHS&IE, UP EXAM YEAR-2021 **** FINAL CENTRE ALLOTMENT REPORT **** DIST-CD & NAME :- 62 AYODHYA PAGE:- 1 CENT-CODE & NAME EXAM SCH-STATUS SCHOOL CODE & NAME #SCHOOL-ALLOT SEX PART GROUP 1003 CANOSSA CONVENT GIRLS INTER COLLEGE AYODHYA BUF HIGH BUF 1001 SAHABDEENRAM SITARAM BALIKA I C AYODHYA 73 F HIGH BUF 1003 CANOSSA CONVENT GIRLS INTER COLLEGE AYODHYA 225 F 298 INTER BUF 1002 METHODIST GIRLS INTER COLLEGE AYODHYA 56 F OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER BUF 1003 CANOSSA CONVENT GIRLS INTER COLLEGE AYODHYA 109 F OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER BUF 1003 CANOSSA CONVENT GIRLS INTER COLLEGE AYODHYA 111 F SCIENCE INTER CUM 1091 DARSGAH E ISLAMI INTER COLLEGE AYODHYA 53 F ALL GROUP 329 CENTRE TOTAL >>>>>> 627 1004 GOVT GIRLS I C GOSHAIGANJ AYODHYA AUF HIGH AUF 1004 GOVT GIRLS I C GOSHAIGANJ AYODHYA 40 F HIGH CRF 1125 VIDYA DEVIGIRLS I C ANKARIPUR AYODHYA 11 F HIGH CRM 1140 SARDAR BHAGAT SINGH HS BARAIPARA DULLAPUR AYODHYA 20 F HIGH CRM 1208 M D M N ARYA HSS R N M G GANJ AYODHYA 7 F HIGH CUM 1265 A R A IC K GADAR RD GOSAINGANJ AYODHYA 32 F HIGH CRM 1269 S S M HSS K G ROAD GOSHAINGANJ AYODHYA 26 F HIGH CRM 1276 IMAMIA H S S AMSIN AYODHYA 15 F HIGH AUF 5004 GOVT GIRLS I C GOSHAIGANJ AYODHYA 18 F 169 INTER AUF 1004 GOVT GIRLS I C GOSHAIGANJ AYODHYA 43 F OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER CRF 1075 MADHURI GIRLS I C AMSIN AYODHYA 91 F OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER CRF 1125 VIDYA DEVIGIRLS I C ANKARIPUR AYODHYA 7 F OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER CRM 1138 AMIT ALOK I C BODHIPUR AMSIN AYODHYA 96 F OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER CUM 1265 A R A IC K GADAR RD GOSAINGANJ AYODHYA 74 -

Tirupati City with Many Slums ; an Ill Health Environment to the Piligirim Centre” in Martin J

Krishnaiah, Dr. K. “Tirupati City With Many Slums ; An Ill Health Environment To The Piligirim Centre” in Martin J. Bunch, V. Madha Suresh and T. Vasantha Kumaran, eds., Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Environment and Health, Chennai, India, 15-17 December, 2003. Chennai: Department of Geography, University of Madras and Faculty of Environmental Studies, York University. Pages 226 – 232. TIRUPATI CITY WITH MANY SLUMS ; AN ILL HEALTH ENVIRONMENT TO THE PILIGIRIM CENTRE Dr. K. Krishnaiah Associate Professor, Department of Geography, S.V.University, Tirupati- 517 502 Abstract Industrialisation results in increasing urbanization. The accumulation of wealth and availability of more economic and job opportunities in the urban centres have resulted in the concentration of the population in the congested metropolitan areas and thus the formation and growth of big slum areas. These slum centres, when combined with industrial sectors, become more hazardous from the stand point of environmental degradation and pollution. If these slum centres are many, it is hazardous and causes ill health to the city like Tirupati, an important piligrim centre in the country. In the present study the emphasis was on the ratio of the total number of slums. 42 were identified in the small area 0.715 sq. km as per 2001 census in Tirupati. The author makes a caution that the higher the density of slums in the pilgrim centre, the more will be the ill health environment in terms of spread of diseases. Introduction The phenomenon of rapid urbanization in conjunction with industrialization has resulted in the growth of slums. The sprouting of slums occur due to many factors, such as the shortage of developed land for housing, the high prices of land beyond the reach of urban poor, and a large influx of rural migrants to the cities in search of jobs etc. -

When Yogis Become Warriors—The Embodied Spirituality of Kal.Aripayattu

religions Article When Yogis Become Warriors—The Embodied Spirituality of Kal.aripayattu Maciej Karasinski-Sroka Department of Foreign Languages, Hainan University, Haikou 570208, China; [email protected] Abstract: This study examines the relationship between body and spirituality in kal.aripayattu (kal.arippayattu), a South Indian martial art that incorporates yogic techniques in its training regimen. The paper is based on ethnographic material gathered during my fieldwork in Kerala and interviews with practitioners of kal.aripayattu and members of the Nayar¯ clans. The Nayars¯ of Kerala created their own martial arts that were further developed in their family gymnasia (ka.lari). These ka.laris had their own training routines, initiations and patron deities. Ka.laris were not only training grounds, but temples consecrated with daily rituals and spiritual exercises performed in the presence of masters of the art called gurukkals. For gurukkals, the term ka.lari has a broader spectrum of meaning—it denotes the threefold system of Nayar¯ education: Hindu doctrines, physical training, and yogico-meditative exercises. This short article investigates selected aspects of embodied spirituality in kal.aripayattu and argues that body in kal.ari is not only trained but also textualized and ritualized. Keywords: kal.aripayattu; yoga; embodied spirituality 1. Introduction Ferrer(2008, p. 2) defines embodied spirituality as a philosophy that regards all Citation: Karasinski-Sroka, Maciej. dimensions of human beings –body, soul, spirit, and consciousness—as “equal partners in 2021. When Yogis Become bringing self, community, and world into a fuller alignment with the Mystery out of which Warriors—The Embodied Spirituality everything arises”. In other words, in embodied spirituality, the body is a key tool for of Kal.aripayattu. -

Ancient Wisdom, Modern Life Mount Soma Timeline

Mount Soma Ancient Wisdom, Modern Life Mount Soma Timeline Dr. Michael Mamas came across the information about building an Enlightened City. 1985 Over time, it turned into his Dharmic purpose. November, 2002 The founders of Mount Soma came forth to purchase land. May, 2003 Began cutting in the first road at Mount Soma, Mount Soma Blvd. January, 2005 The first lot at Mount Soma was purchased. May, 2005 First paving of Mount Soma’s main roads. April, 2006 Dr. Michael Mamas had the idea of a Shiva temple at Mount Soma. Marcia and Lyle Bowes stepped forward with the necessary funding to build Sri October, 2006 Somesvara Temple. January, 2007 Received grant approval from Germeshausen Foundation to build the Visitor Center. July, 2007 Received first set of American drawings for Sri Somesvara Temple from the architects. Under the direction of Sthapati S. Santhanakrishnan, a student and relative of Dr. V. July, 2007 Ganapati Sthapati, artisans in India started carving granite for Sri Somesvara Temple. October, 2007 First house finished and occupied at Mount Soma. January, 2008 Groundbreaking for Visitor Center. May, 2008 146 crates (46 tons) of hand-carved granite received from India at Mount Soma. July, 2008 Mount Soma inauguration on Guru Purnima. July/August, 2008 First meditation retreat and class was held at the Visitor Center. February, 2009 Mount Soma Ashram Program began. July, 2009 Started construction of Sri Somesvara Temple. January, 2010 Received grant approval from Germeshausen Foundation to build the Student Union. August, 2010 American construction of Sri Somesvara Temple completed. Sthapati and shilpis arrived to install granite and add Vedic decorative design to Sri October, 2010 Somesvara Temple. -

July (2021), Impact Factor: 7.188 Online Available at Email: [email protected]

ZENITH International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research _________ISSN 2231-5780 Vol.11 (7) July (2021), Impact Factor: 7.188 Online available at www.zenithresearch.org.in Email: [email protected] A TOURISM PROSPECT OF RELIGIOUS DESTINATION OF UTTAR PRADESH WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO NAIMISARANYA (NEEMSAAR) VINOD KUMAR PANDEY PROF. M K AGARWAL SUJAY VIKRAM SINGH Research Scholar Head of Department Senior Research Fellow Department of Economics Department of Economics Department of History of Art and Tourism Management University of Lucknow University of Lucknow Banaras Hindu University Abstract The revival of religious sites and its connection with tourism has created keen interest among researchers in recent times. The paper emphasizes the prospect of religious tourism in Naimisranaya as there is dearth of academic research in the selected destination. The study explores issues and suggested promotional strategies for development of tourism industry. Expert interview and secondary sources (news articles, magazine, and reports) were used as data collection source, primary data was collected using purposive sampling. The finding of study offers insights into prospects pioneering roles in key religious sites of Naimisaranya, to create initiatives in rebuilding religious tourism destination. Keywords:Chakrateertha, Naimisaranya,Religious Tourism, Spirituality,Tourism Prospects. Introduction The religious tourism refers to “patterns of travel where visitor fulfil religious needs by visiting places of religious importance and pilgrimages” (Stausberg,2011). Most of the world‟s great religious centres, past and present, have been destinations for pilgrimages - think of the Vatican, Mecca, Jerusalem, Bodh Gaya (where Buddha was enlightened), or Cahokia (the enormous Native American complex near St. Louis). Religion and pilgrimage tourism refers to all travel outside the usual environment for religious purposes, excluding travel for professional purposes (e.g. -

Faith and the Fear of Death Jonathan Jong

Stories of Faith & Science I Faith and the Fear of Death Jonathan Jong The making of a priest takes many years. A calling must be discerned, not only by the individual but by the Church also, who will test him repeatedly by observation and interview. The candidate must be trained and formed in sanctuaries and seminaries and soup kitchens. He must be examined and found — in the words of the ordinal — “to be of godly life and sound learning.” Some of us wonder how we got through; many of us wonder how other people did too. At the end of this process, the act of ordination itself takes no time at all. In the parish church of a medieval Oxford village one mild English summer’s afternoon a few months before my thirtieth birthday, the bishop, his hands like a veil upon my head, his voice grave and tender in equal measure, invokes the Holy Spirit to come down upon this servant of God for the office and work of a priest in the Church. Done. Priest made. I had known since I was sixteen that I was going to be ordained, but neither when nor how. It came to me when, in a Methodist church in my hometown on the northwestern tip of Malaysian Borneo, I asked to hold the pastor’s collar in my own hands, a request he had never heard before but fulfilled anyway. Much has happened since. I moved to New Zealand not long after and majored in experimental psychology — rather than theology, as might be expected of an aspiring cleric.