Central Asia: a History of Cultures, Arts and Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2012 St. Peter's Pikeland Ucc Church History

2012 Author Unknown The wonder of it! Eternity having been set in the tiny acorn of the man called Jesus Christ, waiting to fill the universe with the plantation of mighty Live-oak trees! ST. PETER’S PIKELAND UCC CHURCH HISTORY CHAPTER THREE 1883 THROUGH 2012 When recounting our history – particularly during the latter part of the 20th and the beginning of the 21st centuries – we must recognize and commend the work of our St. Peter’s Angel, Annamae Moore. Officially we call her our Pastoral Coordinator, a role that in many ways only Annamae is uniquely qualified to serve. Our last eight pastors (Siudy, Thompson, Mackey, Langerhans, Hetrich, Lamson, Zehmer and Hanson) have been ably assisted by Annamae. She has an extraordinary bedside manner when calling on the sick or grieving families, she helps every bride with the stress of a wedding day and every Sunday assure that our worship service runs like a finely tuned watch. We thank Annamae for her tireless service and dedicate this chapter of our history to her because she has been and continues to be a major part of our church life. 2 Table of Contents A Message to Our Successors at St. Peters ..................................................................................... 5 Getting to Know St. Peter’s Pikeland in the Larger Context of the United Church of Christ ......... 7 What we believe ......................................................................................................................... 7 UCC Structure:............................................................................................................................ -

Between West and East People of the Globular Amphora Culture in Eastern Europe: 2950-2350 Bc

BETWEEN WEST AND EAST PEOPLE OF THE GLOBULAR AMPHORA CULTURE IN EASTERN EUROPE: 2950-2350 BC Marzena Szmyt V O L U M E 8 • 2010 BALTIC-PONTIC STUDIES 61-809 Poznań (Poland) Św. Marcin 78 Tel. (061) 8536709 ext. 147, Fax (061) 8533373 EDITOR Aleksander Kośko EDITORIAL COMMITEE Sophia S. Berezanskaya (Kiev), Aleksandra Cofta-Broniewska (Poznań), Mikhail Charniauski (Minsk), Lucyna Domańska (Łódź), Viktor I. Klochko (Kiev), Jan Machnik (Kraków), Valentin V. Otroshchenko (Kiev), Petro Tolochko (Kiev) SECRETARY Marzena Szmyt Second Edition ADAM MICKIEWICZ UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF EASTERN STUDIES INSTITUTE OF PREHISTORY Poznań 2010 ISBN 83-86094-07-9 (print:1999) ISBN 978-83-86094-15-8 (CD-ROM) ISSN 1231-0344 BETWEEN WEST AND EAST PEOPLE OF THE GLOBULAR AMPHORA CULTURE IN EASTERN EUROPE: 2950-2350 BC Marzena Szmyt Translated by John Comber and Piotr T. Żebrowski V O L U M E 8 • 2010 c Copyright by B-PS and Author All rights reserved Cover Design: Eugeniusz Skorwider Linguistic consultation: John Comber Prepared in Poland Computer typeset by PSO Sp. z o.o. w Poznaniu CONTENTS Editor’s Foreword5 Introduction7 I SPACE. Settlement of the Globular Amphora Culture on the Territory of Eastern Europe 16 I.1 Classification of sources . 16 I.2 Characteristics of complexes of Globular Amphora culture traits . 18 I.2.1 Complexes of class I . 18 I.2.2 Complexes of class II . 34 I.3 Range of complexes of Globular Amphora culture traits . 36 I.4 Spatial distinction between complexes of Globular Amphora culture traits. The eastern group and its indicators . 42 I.5 Spatial relations of the eastern and centralGlobular Amphora culture groups . -

CENTRAL EURASIAN STUDIES REVIEW (CESR) Is a Publication of the Central Eurasian Studies Society (CESS)

The CENTRAL EURASIAN STUDIES REVIEW (CESR) is a publication of the Central Eurasian Studies Society (CESS). CESR is a scholarly review of research, resources, events, publications and developments in scholarship and teaching on Central Eurasia. The Review appears two times annually (Winter and Summer) beginning with Volume 4 (2005) and is distributed free of charge to dues paying members of CESS. It is available by subscription at a rate of $50 per year to institutions within North America and $65 outside North America. The Review is also available to all interested readers via the web. Guidelines for Contributors are available via the web at http://cess.fas.harvard.edu/CESR.html. Central Eurasian Studies Review Editorial Board Chief Editor: Marianne Kamp (Laramie, Wyo., USA) Section Editors: Perspectives: Robert M. Cutler (Ottawa/Montreal, Canada) Research Reports: Jamilya Ukudeeva (Aptos, Calif., USA) Reviews and Abstracts: Shoshana Keller (Clinton, N.Y., USA), Philippe Forêt (Zurich, Switzerland) Conferences and Lecture Series: Payam Foroughi (Salt Lake City, Utah, USA) Educational Resources and Developments: Daniel C. Waugh (Seattle, Wash., USA) Editors-at-Large: Ali Iğmen (Seattle, Wash., USA), Morgan Liu (Cambridge, Mass., USA), Sebastien Peyrouse (Washington, D.C., USA) English Language Style Editor: Helen Faller (Philadelphia, Penn., USA) Production Editor: Sada Aksartova (Tokyo, Japan) Web Editor: Paola Raffetta (Buenos Aires, Argentina) Editorial and Production Consultant: John Schoeberlein (Cambridge, Mass., USA) Manuscripts and related correspondence should be addressed to the appropriate section editors: Perspectives: R. Cutler, rmc alum.mit.edu; Research Reports: J. Ukudeeva, jaukudee cabrillo.edu; Reviews and Abstracts: S. Keller, skeller hamilton.edu; Conferences and Lecture Series: P. -

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369, Fravardin & l FEZAN A IN S I D E T HJ S I S S U E Federation of Zoroastrian • Summer 2000, Tabestal1 1369 YZ • Associations of North America http://www.fezana.org PRESIDENT: Framroze K. Patel 3 Editorial - Pallan R. Ichaporia 9 South Circle, Woodbridge, NJ 07095 (732) 634-8585, (732) 636-5957 (F) 4 From the President - Framroze K. Patel president@ fezana. org 5 FEZANA Update 6 On the North American Scene FEZ ANA 10 Coming Events (World Congress 2000) Jr ([]) UJIR<J~ AIL '14 Interfaith PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF '15 Around the World NORTH AMERICA 20 A Millennium Gift - Four New Agiaries in Mumbai CHAIRPERSON: Khorshed Jungalwala Rohinton M. Rivetna 53 Firecut Lane, Sudbury, MA 01776 Cover Story: (978) 443-6858, (978) 440-8370 (F) 22 kayj@ ziplink.net Honoring our Past: History of Iran, from Legendary Times EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Roshan Rivetna 5750 S. Jackson St. Hinsdale, IL 60521 through the Sasanian Empire (630) 325-5383, (630) 734-1579 (F) Guest Editor Pallan R. Ichaporia ri vetna@ lucent. com 23 A Place in World History MILESTONES/ ANNOUNCEMENTS Roshan Rivetna with Pallan R. Ichaporia Mahrukh Motafram 33 Legendary History of the Peshdadians - Pallan R. Ichaporia 2390 Chanticleer, Brookfield, WI 53045 (414) 821-5296, [email protected] 35 Jamshid, History or Myth? - Pen1in J. Mist1y EDITORS 37 The Kayanian Dynasty - Pallan R. Ichaporia Adel Engineer, Dolly Malva, Jamshed Udvadia 40 The Persian Empire of the Achaemenians Pallan R. Ichaporia YOUTHFULLY SPEAKING: Nenshad Bardoliwalla 47 The Parthian Empire - Rashna P. -

Simulation of the Potential Impacts of Projected Climate Change on Streamflow in the Vakhsh River Basin in Central Asia Under CMIP5 RCP Scenarios

water Article Simulation of the Potential Impacts of Projected Climate Change on Streamflow in the Vakhsh River Basin in Central Asia under CMIP5 RCP Scenarios Aminjon Gulakhmadov 1,2,3,4 , Xi Chen 1,2,*, Nekruz Gulahmadov 1,3,5, Tie Liu 1 , Muhammad Naveed Anjum 6 and Muhammad Rizwan 5,7 1 State Key Laboratory of Desert and Oasis Ecology, Xinjiang Institute of Ecology and Geography, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Urumqi 830011, China; [email protected] (A.G.); [email protected] (N.G.); [email protected] (T.L.) 2 Research Center for Ecology and Environment of Central Asia, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Urumqi 830011, China 3 Institute of Water Problems, Hydropower and Ecology of the Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Tajikistan, Dushanbe 734042, Tajikistan 4 Ministry of Energy and Water Resources of the Republic of Tajikistan, Dushanbe 734064, Tajikistan 5 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China; [email protected] 6 Department of Land and Water Conservation Engineering, Faculty of Agricultural Engineering and Technology, Pir Mehr Ali Shah Arid Agriculture University Rawalpindi, Rawalpindi 46000, Pakistan; [email protected] 7 Key Laboratory of Remote Sensing and Geospatial Science, Northwest Institute of Eco-Environment and Resources, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Lanzhou 730000, China * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-136-0992-3012 Received: 1 April 2020; Accepted: 15 May 2020; Published: 17 May 2020 Abstract: Millions of people in Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan are dependent on the freshwater supply of the Vakhsh River system. Sustainable management of the water resources of the Vakhsh River Basin (VRB) requires comprehensive assessment regarding future climate change and its implications for streamflow. -

The Shared Lexicon of Baltic, Slavic and Germanic

THE SHARED LEXICON OF BALTIC, SLAVIC AND GERMANIC VINCENT F. VAN DER HEIJDEN ******** Thesis for the Master Comparative Indo-European Linguistics under supervision of prof.dr. A.M. Lubotsky Universiteit Leiden, 2018 Table of contents 1. Introduction 2 2. Background topics 3 2.1. Non-lexical similarities between Baltic, Slavic and Germanic 3 2.2. The Prehistory of Balto-Slavic and Germanic 3 2.2.1. Northwestern Indo-European 3 2.2.2. The Origins of Baltic, Slavic and Germanic 4 2.3. Possible substrates in Balto-Slavic and Germanic 6 2.3.1. Hunter-gatherer languages 6 2.3.2. Neolithic languages 7 2.3.3. The Corded Ware culture 7 2.3.4. Temematic 7 2.3.5. Uralic 9 2.4. Recapitulation 9 3. The shared lexicon of Baltic, Slavic and Germanic 11 3.1. Forms that belong to the shared lexicon 11 3.1.1. Baltic-Slavic-Germanic forms 11 3.1.2. Baltic-Germanic forms 19 3.1.3. Slavic-Germanic forms 24 3.2. Forms that do not belong to the shared lexicon 27 3.2.1. Indo-European forms 27 3.2.2. Forms restricted to Europe 32 3.2.3. Possible Germanic borrowings into Baltic and Slavic 40 3.2.4. Uncertain forms and invalid comparisons 42 4. Analysis 48 4.1. Morphology of the forms 49 4.2. Semantics of the forms 49 4.2.1. Natural terms 49 4.2.2. Cultural terms 50 4.3. Origin of the forms 52 5. Conclusion 54 Abbreviations 56 Bibliography 57 1 1. -

Ebook Download Greek Art 1St Edition

GREEK ART 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Nigel Spivey | 9780714833682 | | | | | Greek Art 1st edition PDF Book No Date pp. Fresco of an ancient Macedonian soldier thorakitai wearing chainmail armor and bearing a thureos shield, 3rd century BC. This work is a splendid survey of all the significant artistic monuments of the Greek world that have come down to us. They sometimes had a second story, but very rarely basements. Inscription to ffep, else clean and bright, inside and out. The Erechtheum , next to the Parthenon, however, is Ionic. Well into the 19th century, the classical tradition derived from Greece dominated the art of the western world. The Moschophoros or calf-bearer, c. Red-figure vases slowly replaced the black-figure style. Some of the best surviving Hellenistic buildings, such as the Library of Celsus , can be seen in Turkey , at cities such as Ephesus and Pergamum. The Distaff Side: Representing…. Chryselephantine Statuary in the Ancient Mediterranean World. The Greeks were quick to challenge Publishers, New York He and other potters around his time began to introduce very stylised silhouette figures of humans and animals, especially horses. Add to Basket Used Hardcover Condition: g to vg. The paint was frequently limited to parts depicting clothing, hair, and so on, with the skin left in the natural color of the stone or bronze, but it could also cover sculptures in their totality; female skin in marble tended to be uncoloured, while male skin might be a light brown. After about BC, figures, such as these, both male and female, wore the so-called archaic smile. -

M. Witzel (2003) Sintashta, BMAC and the Indo-Iranians. a Query. [Excerpt

M. Witzel (2003) Sintashta, BMAC and the Indo-Iranians. A query. [excerpt from: Linguistic Evidence for Cultural Exchange in Prehistoric Western Central Asia] (to appear in : Sino-Platonic Papers 129) Transhumance, Trickling in, Immigration of Steppe Peoples There is no need to underline that the establishment of a BMAC substrate belt has grave implications for the theory of the immigration of speakers of Indo-Iranian languages into Greater Iran and then into the Panjab. By and large, the body of words taken over into the Indo-Iranian languages in the BMAC area, necessarily by bilingualism, closes the linguistic gap between the Urals and the languages of Greater Iran and India. Uralic and Yeneseian were situated, as many IIr. loan words indicate, to the north of the steppe/taiga boundary of the (Proto-)IIr. speaking territories (§2.1.1). The individual IIr. languages are firmly attested in Greater Iran (Avestan, O.Persian, Median) as well as in the northwestern Indian subcontinent (Rgvedic, Middle Vedic). These materials, mentioned above (§2.1.) and some more materials relating to religion (Witzel forthc. b) indicate an early habitat of Proto- IIr. in the steppes south of the Russian/Siberian taiga belt. The most obvious linguistic proofs of this location are the FU words corresponding to IIr. Arya "self-designation of the IIr. tribes": Pre-Saami *orja > oarji "southwest" (Koivulehto 2001: 248), ārjel "Southerner", and Finnish orja, Votyak var, Syry. ver "slave" (Rédei 1986: 54). In other words, the IIr. speaking area may have included the S. Ural "country of towns" (Petrovka, Sintashta, Arkhaim) dated at c. -

CBD Strategy and Action Plan

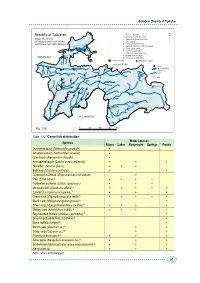

Biological Diversity of Tajikistan Republic of Tajikistan The Legend: 1 - Acipenser nudiventris Lovet 2 - Salmo trutta morfa fario Linne ya 3 - A.a.a. (Linne) ar rd Sy 4 - Ctenopharyngodon idella Kayrakkum reservoir 5 - Hypophthalmichtus molitrix (Valenea) Khujand 6 - Silurus glanis Linne 7 - Cyprinus carpio Linne a r a 8 - Lucioperca lucioperea Linne f s Dagano-Say I 9 - Abramis brama (Linne) reservoir UZBEKISTAN 10 -Carassus auratus gibilio Katasay reservoir economical pond distribution location KYRGYZSTAN cities Zeravshan lakes and water reservoirs Yagnob rivers Muksu ob Iskanderkul Lake Surkh o CHINA b r Karakul Lake o S b gou o in h l z ik r b e a O b V y u k Dushanbe o ir K Rangul Lake o rv Shorkul Lake e P ch z a n e n a r j V ek em Nur gul Murg u az ab s Y h k a Y u ng Sarez Lake s l ta i r a u iz s B ir K Kulyab o T Kurgan-Tube n a g i n r Gunt i Yashilkul Lake f h a s K h Khorog k a Zorkul Lake V Turumtaikul Lake ra P a an d j kh Sha A AFGHANISTAN m u da rya nj a P Fig. 1.16. 0 50 100 150 Km Table 1.12. Game fish distribution Water sources Species Rivers Lakes Reservoirs Springs Ponds Dushanbe loach (Nemachilus pardalis) + Amudarya loach (Nemachilus oxianus) + Gray loach (Nemachilus dorsalis) + Aral spined loach (Cobitis aurata aralensis) + + + Sheatfish (Sclurus glanis) + + + Bullhead (Ictalurus punctata) А + + Turkestan bullhead (Glyptosternum reticulatum) + Pike (Esox lucius) + + + + Turkestan bullhead (Cottus spinolosus) + + + Mosquito fish (Gambusia affinis) А + + + + + Zander (Lucioperca lucioperea) А + + + Grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon della) А + + + + + Black carp (Mylopharyngodon piceus) А + Silver carp (Hypophthalmichthus molitrix) А + + + + Motley carp (Aristichthus nobilis) А + + + + Big-mouthed buffalo (Ictiobus cyprinellus) А + Small-mouthed buffalo (I.bufalus) А + Black buffalo (I.niger) А + Mirror carp (Cyprinus sp.) А + + Scaly carp (Cyprinus sp.) А + + Pseudorasbora parva А + + + Amur goby (Neogobius amurensis sp.) А + + + Snakehead (Ophiocephalus argus warpachowski) А + + + Hemiculter sp. -

Central Asia in Xuanzang's Great Tang Dynasty Record of the Western

Recording the West: Central Asia in Xuanzang’s Great Tang Dynasty Record of the Western Regions Master’s Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master Arts in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Laura Pearce Graduate Program in East Asian Studies Ohio State University 2018 Committee: Morgan Liu (Advisor), Ying Zhang, and Mark Bender Copyrighted by Laura Elizabeth Pearce 2018 Abstract In 626 C.E., the Buddhist monk Xuanzang left the Tang Empire for India in a quest to deepen his religious understanding. In order to reach India, and in order to return, Xuanzang journeyed through areas in what is now called Central Asia. After he came home to China in 645 C.E., his work included writing an account of the countries he had visited: The Great Tang Dynasty Record of the Western Regions (Da Tang Xi You Ji 大唐西域記). The book is not a narrative travelogue, but rather presented as a collection of facts about the various countries he visited. Nevertheless, the Record is full of moral judgments, both stated and implied. Xuanzang’s judgment was frequently connected both to his Buddhist beliefs and a conviction that China represented the pinnacle of culture and good governance. Xuanzang’s portrayal of Central Asia at a crucial time when the Tang Empire was expanding westward is both inclusive and marginalizing, shaped by the overall framing of Central Asia in the Record and by the selection of local legends from individual nations. The tension in the Record between Buddhist concerns and secular political ones, and between an inclusive worldview and one centered on certain locations, creates an approach to Central Asia unlike that of many similar sources. -

Ulug-Depe and the Transition Period from Bronze Age to Iron Age in Central Asia

Ulug-depe and the transition period from Bronze Age to Iron Age in Central Asia. A tribute to V.I. Sarianidi Johanna Lhuillier To cite this version: Johanna Lhuillier. Ulug-depe and the transition period from Bronze Age to Iron Age in Central Asia. A tribute to V.I. Sarianidi . Dubova, N.A., Antonova, E.V., Kozhin, P.M., Kosarev, M.F., Muradov, R.G., Sataev, R.M. & Tishkin A.A. Transactions of Margiana Archaeological Expedition, To the memory of Professor Viktor Sarianidi, 6, Staryj Sad, pp.509-521, 2016, 978-5-89930-150-6. halshs-01534928 HAL Id: halshs-01534928 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01534928 Submitted on 8 Jun 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. N.N. MIKLUKHO-MAKLAY INSTITUTE OF ETHNOLOGY AND ANTHROPOLOGY OF RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES MARGIANA ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXPEDITION ALTAY STATE UNIVERSITY TRANSACTIONS OF MARGIANA ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXPEDITION Volume 6 To the Memory of Professor Victor Sarianidi Editorial board N.A. Dubova (editor in chief), E.V. Antonova, P.M. Kozhin, M.F. Kosarev, R.G. Muradov, R.M. Sataev, A.A. Tishkin Moscow 2016 Туркменистан, Гонур-депе, 9 октября 2005 г. -

A Study on the Scythian Torque

IJCC, Vol, 6, No. 2, 69〜82(2003) A Study on the Scythian Torque Moon-Ja Kim Professor, Dept, of Clothing & Textiles, Suwon University (Received May 2, 2003) Abstract The Scythians had a veritable passion for adornment, delighting in decorating themselves no less than their horses and belongings. Their love of jewellery was expressed at every turn. The most magnificent pieces naturally come from the royal tombs. In the area of the neck and chest the Scythian had a massive gold Torques, a symbol of power, made of gold, turquoise, cornelian coral and even amber. The entire surface of the torque, like that of many of the other artefacts, is decorated with depictions of animals. Scythian Torques are worn with the decorative terminals to the front. It was put a Torque on, grasped both terminals and placed the opening at the back of the neck. It is possible the Torque signified its wearer's religious leadership responsibilities. Scythian Torques were divided into several types according to the shape, Torque with Terminal style, Spiral style, Layers style, Crown style, Crescent-shaped pectoral style. Key words : Crescent-shaped pectoral style, Layers style, Scythian Torque, Spiral style, Terminal style role in the Scythian kingdom belonged to no I • Introduction mads and it conformed to nomadic life. A vivid description of the burial of the Scythian kings The Scythians originated in the central Asian and of ordinary members of the Scythian co steppes sometime in the early first millennium, mmunity is contained in Herodotus' History. The BC. After migrating into what is present-day basic characteristics of the Scythian funeral Ukraine, they flourished, from the seventh to the ritual (burials beneath Kurgans according to a third centuries, BC, over a vast expanse of the rite for lating body in its grave) remained un steppe that stretched from the Danube, east changed throughout the entire Scythian period.^ across what is modem Ukraine and east of the No less remarkable are the articles from the Black Sea into Russia.