Critical Reflections of Filipino American Students A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of Filipino Immigrant Labor in Seattle from 1920-1940

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection Undergraduate Scholarship 4-22-2011 Shallow Roots: An Analysis of Filipino Immigrant Labor in Seattle from 1920-1940 Krista Baylon Sorenson Butler University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Baylon Sorenson, Krista, "Shallow Roots: An Analysis of Filipino Immigrant Labor in Seattle from 1920-1940" (2011). Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection. 98. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses/98 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Shallow Roots: An Analysis of Filipino Immigrant Labor in Seattle from 1920-1940 A Thesis Presented to the Department of History College of Liberal Arts and Sciences and The Honors Program of Butler University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation Honors Krista Baylon Sorenson April 22, 2011 Sorenson 1 “Why was America so kind and yet so cruel? Was there no way to simplify things in this continent so that suffering would be minimized? Was there not common denominator on which we could all meet? I was angry and confused and wondered if I would ever understand this paradox?”1 “It was a planless life, hopeless, and without direction. I was merely living from day to day: yesterday seemed long ago and tomorrow was too far away. It was today that I lived for aimlessly, this hour-this moment.”2 -Carlos Bulosan, America is in the Heart Introduction Carlos Bulosan was a Filipino immigrant living in the United States beginning in the 1930s. -

CATALLA-DISSERTATION-2019.Pdf (3.265Mb)

KUWENTO/STORIES: A NARRATIVE INQUIRY OF FILIPINO AMERICAN COMMUNITY COLLEGE STUDENTS _____________ A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Educational Leadership Sam Houston State University _____________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education _____________ by Pat Lindsay Carijutan Catalla May, 2019 KUWENTO/STORIES: A NARRATIVE INQUIRY OF FILIPINO AMERICAN COMMUNITY COLLEGE STUDENTS by Pat Lindsay Carijutan Catalla ______________ APPROVED: Paul William Eaton, PhD Dissertation Director Rebecca Bustamante, PhD Committee Member Ricardo Montelongo, PhD Committee Member Stacey Edmonson, PhD Dean, College of Education DEDICATION I dedicate this body of work to my family, ancestors, friends, colleagues, dissertation committee, Filipino American community, and my future self. I am deeply thankful for all the support each person has given me through the years in the doctoral program. This is a journey I will never, ever forget. iii ABSTRACT Catalla, Pat Lindsay Carijutan, Kuwento/Stories: A narrative inquiry of Filipino American Community College students. Doctor of Education (Education), May, 2019, Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, Texas. The core of this narrative inquiry is the kuwento, story, of eight Filipino American community college students (FACCS) in the southern part of the United States. Clandinin and Connelly’s (2000) three-dimension inquiry space—inwards, outwards, backwards, and forwards—provided a space for the characters, Bunny, Geralt, Jay, Justin, Ramona, Rosalinda, Steve, and Vivienne, to reflect upon their educational, career, and life experiences as a Filipino American. The character’s stories are delivered in a long, uninterrupted kuwento, encouraging critical discourse around their Filipino American identity development and educational struggles as a minoritized student in higher education. -

Special Collections Division University of Washington Libraries Box 352900 Seattle, Washington, 98195-2900 USA (206) 543-1929

Special Collections Division University of Washington Libraries Box 352900 Seattle, Washington, 98195-2900 USA (206) 543-1929 This document forms part of the Preliminary Guide to the Cannery Workers and Farm Laborers Union Local 7 Records. To find out more about the history, context, arrangement, availability and restrictions on this collection, click on the following link: http://digital.lib.washington.edu/findingaids/permalink/CanneryWorkersandFarmLaborersUnionLocal7SeattleWash3927/ Special Collections home page: http://www.lib.washington.edu/specialcollections/ Search Collection Guides: http://digital.lib.washington.edu/findingaids/search CANNERY WORKERS' AND FARM LABORERS' UNION. LOCAL NO. 7 1998 UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON LIBRARIES MANUSCRIPTS AND UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES CANNERY WORKERS' AND FARM LABORERS' UNION. LOCAL NO. 7 Accession No. 3927-001 GUIDE HISTORY The Cannery Workers' and Farm Laborers' Union was organized June 19, 1933 in Seattle to represent the primarily Filipino-American laborers who worked in the Alaska salmon canneries. Filipino Alaskeros first appeared in the canneries around 1911. In the 1920s as exclusionary immigration laws went into effect, they replaced the Japanese, who had replaced the Chinese in the canneries. Workers were recruited through labor contractors who were paid to provide a work crew for the summer canning season. The contractor paid workers wages and other expenses. This system led to many abuses and harsh working conditions from which grew the movement toward unionization. The CWFLU, under the leadership of its first President, Virgil Duyungan, was chartered as Local 19257 by the American Federation of Labor in 1933. On December 1, 1936 an agent of a labor contractor murdered Duyungan and Secretary Aurelio Simon. -

EMPOWERING OUR COMMUNITIES Asian American Story

EMPOWERING OUR COMMUNITIES Asian American Story Chinese miners in Auburn Ravine, California in early 1850s. A ‘Chinatown’ in Virginia City, Nevada in late 1870s. Source: Lee, Josephine. Early Asian America, 2002. Asian American Story Filipino plantation laborers Sikh immigrants working on the arriving in Honolulu. A Korean rice farmer in California in 1920. farm fields near Fresno, California. Source: Takaki. Strangers from a Different Shore, 1989. Past Challenges • Economic freedom • Political freedom • Establishing community & family • Native rights or citizenship • Empowerment & Civil Rights ANYTHING DIFFERENT TODAY? Seeking Equal Status • Gaining citizenship - 1943 Magnuson Act, repealed the Chinese Exclusion Act; Chinese now eligible for naturalization. - 1952 Immigration and Nationality Act; Asians and persons of all races eligible to immigration and naturalization. Organizing for Workers’ Rights • Empowerment & Civil Rights - 1933, Cannery Workers’ and Farm Laborer’ Union formed in Seattle. Cannery workers in 1926. Filipino salmon processing workers in Alaska, known Union pioneers Virgil Duyungan, as the "Alaskeros." Tony Rodrigo, CB Mislang, Espiritu in 1933. Source: http://depts.washington.edu/civilr/cwflu.htm Breaking the Silence • Empowerment & Civil Rights – 1989, President George Bush (Sr.) signs into law Redress Entitlement Program. Source: Takaki. Strangers from a Different Source: Nikkei for Civil Rights and Redress Shore, 1989. http://www.ncrr-la.org/ Increasing Visibility • Economic Justice Southeast Asian community members protesting 1996 welfare ‘reform’. 1946 Sugar Laborers’ Strike in Hawaii. Source: Foo. Asian American Women, 2003. Source: Takaki. Strangers from a Different Shore, 1989. Using the Law • Economic Justice Vietnamese Fishermen's Association v. Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, 518 F. Supp. 993, 1010 (S.D. -

2006 Presldenllalawardees Who Have Shown Lhe Best of the Fil,Plno

MALACANAN PALACE ",,",LA Time and again I have acknowledged the Invaluable contribuhOn ofour overseas Filipinos to national development and nation build Lng They have shared their skills and expertise to enable the Philippines to benefit from advances in sCience and technology RemiUing more than $70 billion in the last ten years, they have contributed Slgnlficanlly to our counlry's economic stability and social progress of our people. Overseas Filipinos have also shown that they are dependable partners, providl!'lQ additional resources to augment programs in health, educatIOn, livelihood projects and small infrastructure in the country, We pay tnbute to Filipinos overseas who have dedicated themselves to uplifting the human condiloOn, those who have advocated the cause of Filipinos worldwide, and who continue to bring pride and honor to lhe Philippines by their pursuit of excellence I ask the rest of the FilipinO nation to Join me in congratulating the 2006 PreSldenllalAwardees who have shown lhe best of the Fil,plno. I also extend my thanks to the men and women of the CommiSSion on Filipinos Overseas and the vanous Awards commillees for a job well done in thiS biennial search. Mabuhay kayong lahalr Mantia. 7 Decemoor 2006 , Office of Itle Pres,dent of !he Ph''PP'nes COMMISSION ON FILIPINOS OVERSEAS Today, some 185 million men, women and even children, represent,rog about 3 percent of the world's population, live Ofwork outside their country of origin. No reg,on in the world is WIthout migrants who live or work within its borders Every country is now an origin ordeslination for international migration. -

Redalyc.Filipinos in the U.S.: Historical, Social, and Educational

Social and Education History E-ISSN: 2014-3567 [email protected] Hipatia Press España Paik, Susan J.; Mamaril Choe, Shirlie Mae; Witenstein, Matthew A. Filipinos in the U.S.: Historical, Social, and Educational Experiences Social and Education History, vol. 5, núm. 2, junio, 2016, pp. 134-160 Hipatia Press Barcelona, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=317046062002 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Instructions for authors, subscriptions and further details: http://hse.hipatiapress.com Filipinos in the U.S.: Historical, Social, and Educational Experiences Susan J. Paik1, Shirlie Mae Mamaril Choe1, Matthew A. Witenstein2 1) Claremont Graduate University (USA) 2) University of San Diego (USA) Date of publication: June 23rd, 2016 Edition period: June 2016 – October 2016 To cite this article: Paik, S.J., Choe, S.M.M., & Witenstein, M.A. (2016). Filipinos in the U.S.: Historical, Social, and Educational Experiences. Social and Education History 5(2), 134-160. doi:10.17583/hse.2016.2062 To link this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.17583/hse.2016.2062 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE The terms and conditions of use are related to the Open Journal System and to Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY). HSE – Social and Education History Vol. 5 No. 2 June 2016 pp.134- 160 Filipinos in the U.S.: Historical, Social, and Educational Experiences Susan J. -

Food, Tobacco, Agricultural and Allied Workers of America (Fta) and Related Agricultural Unions Records

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf6c60050c No online items Inventory of the Food, Tobacco, Agricultural and Allied Workers of America (Fta) and Related Agricultural Unions Records. The Norman Leonard Collection, 1936 - 1950 Processed by The Labor Archives & Research Center staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Xiuzhi Zhou Labor Archives and Research Center San Francisco State University 480 Winston Drive San Francisco, California 94132 Phone: (415) 564-4010 Fax: (415) 564-3606 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.sfsu.edu/special/larc.html © 1999 San Francisco State University. All rights reserved. 1985/006 1 Inventory of the Food, Tobacco, Agricultural and Allied Workers of America (Fta) and Related Agricultural Unions Records. The Norman Leonard Collection, 1936 - 1950 Accession number: 1985/006 Labor Archives & Research Center San Francisco State University San Francisco, California Contact Information: Labor Archives & Research Center San Francisco State University 480 Winston Drive San Francisco, California 94132 Phone: (415) 564-4010 Fax: (415) 564-3606 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.sfsu.edu/special/larc.html Processed by: The Labor Archives & Research Center staff Encoded by: Xiuzhi Zhou © 1999 San Francisco State University. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Food, Tobacco, Agricultural and Allied Workers of America (Fta) and Related Agricultural Unions Records. The Norman Leonard Collection, Date (inclusive): 1936 - 1950 Accession number: 1985/006 Creator: Leonard, Norman Repository: San Francisco State University. Labor Archives & Research Center San Francisco, California 94132 Shelf location: For current information on the location of these materials, please consult the Center's online catalog. Language: English. Access Collection is open for research. -

Filipino Americans in Los Angeles Historic Context Statement

LOS ANGELES CITYWIDE HISTORIC CONTEXT STATEMENT Context: Filipino Americans in Los Angeles, 1903-1980 Prepared for: City of Los Angeles Department of City Planning Office of Historic Resources August 2018 National Park Service, Department of the Interior Grant Disclaimer This material is based upon work assisted by a grant from the Historic Preservation Fund, National Park Service, Department of the Interior. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of the Interior. SurveyLA Citywide Historic Context Statement Filipino Americans in Los Angeles, 1903-1980 TABLE OF CONTENTS PURPOSE AND SCOPE 1 CONTRIBUTORS 1 PREFACE 2 HISTORIC CONTEXT 10 Introduction 10 Terms and Definitions 10 Beginnings, 1898-1903 11 Early Filipino Immigration to Southern California, 1903-1923 12 Filipino Settlement in Los Angeles: Establishing a Community, 1924-1945 16 Post-World War II and Maturing of the Community, 1946-1964 31 Filipino American Los Angeles, 1965-1980 42 ASSOCIATED PROPERTY TYPES AND ELIGIBILITY REQUIREMENTS 49 BIBLIOGRAPHY 73 APPENDICES: Appendix A: Filipino American Known and Designated Resources Appendix B: SurveyLA’s Asian American Historic Context Statement Advisory Committee SurveyLA Citywide Historic Context Statement Filipino Americans in Los Angeles, 1903-1980 PURPOSE AND SCOPE In 2016, the City of Los Angeles Office of Historic Resources (OHR) received an Underrepresented Communities grant from the National Park Service to develop a National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form (MPDF) and associated historic contexts for five Asian American communities in Los Angeles: Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Thai, and Filipino. -

Exploring the Development Trend of Chinese Education in the Tertiary Level (Philippines)

EXPLORING THE DEVELOPMENT TREND OF CHINESE EDUCATION IN THE TERTIARY LEVEL (PHILIPPINES) PROF. DAISY CHENG SEE ABSTRACT This paper traces the changes and developments in Chinese education in the Philippines by a survey of the history thereof. It discusses how Chinese education developed from an education catered to a small number of overseas Chinese to the ethnic Chinese, from an education of students of Chinese descent to mainstream Philippine society in the tertiary level, and the role played by the socio-political environment in this regard. This paper also seeks to answer the question of whether the policy of the Philippine government has anything to do with this development. Difficulties and obstacles to this type of education are discussed. Through an evaluation of the foregoing, this paper proposes some solutions to the perceived problems. This paper uses the investigative exploratory method of study. Books and relevant publications are utilized where necessary. Materials from the Internet from recognized institutions are also used as reference. Interviews and surveys were also conducted in the process of this study. Keywords: Mandarin Linguistic routines; Digital storytelling, Communicative Approach CHINESE STUDIES PROGRAM LECTURE SERIES © Ateneo de Manila University No. 3, 2016: 56–103 http://journals.ateneo.edu SEE / DEVELOPMENT TREND OF CHINESE EDUCATION 57 hinese education in the Philippines refers to the education C taught to ethnic Chinese who became Filipino citizens in Chinese schools after Filipinization.1 Chinese schools have already systematically turned into private Filipino schools that taught the Chinese language (Constitution of the Philippines, 1973).2 Basically, this so-called “Chinese-Filipino education” must have begun in 1976, when Chinese schools in the Philippines underwent comprehensive Filipinization. -

Copyright by Shannon Guillot-Wright 2018

Copyright by Shannon Guillot-Wright 2018 The Dissertation Committee for Shannon Guillot-Wright Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Casting Aside Bent Bodies: Embodied Violence as an Everyday Experience for Filipino Migrant Seafarers Committee: Arlene Macdonald, PhD, Supervisor and Chair Rebecca Hester, PhD, Mentor and Co-Chair Jerome Crowder, PhD Premal Patel, MD William Terry, PhD _______________________________ David W. Niesel, PhD Dean, Graduate School Casting Aside Bent Bodies: Embodied Violence as an Everyday Experience for Filipino Migrant Seafarers by Shannon Guillot-Wright, MA Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas Medical Branch in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Medical Humanities The University of Texas Medical Branch November, 2018 Dedication “In the book there will be no dedication (for I can’t give you what has been yours from the beginning) but instead: From the property of…” –Rainer Marie Rilke, Duino Elegies From the property of: The men and women who live and work at sea Acknowledgements I am grateful to the Institute for the Medical Humanities and the Center to Eliminate Health Disparities for financial and intellectual support in the form of assistantships, scholarships, and fellowships. I am also thankful to the Harry Huntt Ransom Dissertation Fellowship Award in the Medical Humanities and the Chester R. Burns Institute for the Medical Humanities Alumni Award for helping to make this research richer, and to the John P. McGovern Academy of Oslerian Medicine for making the photovoice project and gallery showing possible. -

THE LIFE and TIMES of CARLOS BULOSAN a Thesis

KAIN NA! THE LIFE AND TIMES OF CARLOS BULOSAN A Thesis Presented to the faculty of the Department of History California State University, Sacramento Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History by Donald Estrella Piring, Jr. FALL 2016 © 2016 Donald Estrella Piring, Jr. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii Preface This thesis, Kain Na!, began as a project in Fall 2015.1 It was based on a historic community of Filipino migrant workers and shopkeepers – Little Manila in Stockton, California. America’s legalized racism and American citizens’ individual prejudices segregated Asian migrant workers to designated districts, one of which was Stockton’s Little Manila. The immigrants were expressly forbidden from leaving these districts, except for work or out-of-town travel. The history of just one community is too broad for one paper, and so the project was repurposed to examine just one individual – Allos “Carlos” Bulosan, Filipino writer and labor organizer. There are some limitations to the study. Attempts were made to contact Dr. Dawn Mabalon at San Francisco State University and Conor M. Casey at the University of Washington, Seattle. Most of the materials consulted during the Fall 2015 semester were fiction and prose written by Bulosan. One year later, archival materials were consulted and this thesis was written. There was insufficient time to reread all the materials with new evidence and insights. Not all of the known Bulosan materials (in the UW Seattle Special Collections or elsewhere) were examined. Microfilm and audio cassettes were not consulted, lest they become damaged in the research process. -

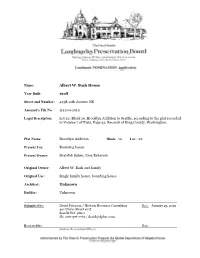

Albert W. Bash House Year Built: 1908 Street and Number

Name: Albert W. Bash House Year Built: 1908 Street and Number: 4238 12th Avenue NE Assessor's File No. 114200-1010 Legal Description: Lot 22, Block 10, Brooklyn Addition to Seattle, according to the plat recorded in Volume 7 of Plats, Page 32, Records of King County, Washington. Plat Name: Brooklyn Addition Block: 10 Lot: 22 Present Use: Rooming house Present Owner: Sharifah Sabah, Lina Baharain Original Owner: Albert W. Bash and family Original Use: Single family house, boarding house Architect: Unknown Builder: Unknown Submitted by: David Peterson / Historic Resource Consulting Date: January 25, 2019 301 Union Street #115 Seattle WA 98111 Ph: 206-376-7761 / [email protected] Reviewed by: Date: (Historic Preservation Officer) Albert W. Bash house 4238 12th Avenue NE Seattle Landmarks Preservation Board January 25, 2019 (revised March 12, 2019) David Peterson historic resource consulting 301 Union Street #115 Seattle WA 98111 P:206-376-7761 [email protected] Albert W. Bash House - 4238 12th Avenue NE Seattle Landmark Nomination INDEX I. Introduction 3 II. Building information 3 III. Architectural description 4 A. Site and neighborhood context B. Building description C. Summary of primary alterations IV. Historical context 7 A. The development of the University District neighborhood B. Building owners and occupants C. The subject property as a rooming house a. Rooming house b. Filipino student house D. Filipino Americans in Seattle E. The American Foursquare house V. Bibliography and sources 21 VI. List of Figures 23 Illustrations 24-55 Site Plan / Survey Following Selected drawings Following David Peterson historic resource consulting – Seattle Landmark Nomination – Albert W.