Copyright by Shannon Guillot-Wright 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc.Filipinos in the U.S.: Historical, Social, and Educational

Social and Education History E-ISSN: 2014-3567 [email protected] Hipatia Press España Paik, Susan J.; Mamaril Choe, Shirlie Mae; Witenstein, Matthew A. Filipinos in the U.S.: Historical, Social, and Educational Experiences Social and Education History, vol. 5, núm. 2, junio, 2016, pp. 134-160 Hipatia Press Barcelona, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=317046062002 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Instructions for authors, subscriptions and further details: http://hse.hipatiapress.com Filipinos in the U.S.: Historical, Social, and Educational Experiences Susan J. Paik1, Shirlie Mae Mamaril Choe1, Matthew A. Witenstein2 1) Claremont Graduate University (USA) 2) University of San Diego (USA) Date of publication: June 23rd, 2016 Edition period: June 2016 – October 2016 To cite this article: Paik, S.J., Choe, S.M.M., & Witenstein, M.A. (2016). Filipinos in the U.S.: Historical, Social, and Educational Experiences. Social and Education History 5(2), 134-160. doi:10.17583/hse.2016.2062 To link this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.17583/hse.2016.2062 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE The terms and conditions of use are related to the Open Journal System and to Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY). HSE – Social and Education History Vol. 5 No. 2 June 2016 pp.134- 160 Filipinos in the U.S.: Historical, Social, and Educational Experiences Susan J. -

Filipino Americans in Los Angeles Historic Context Statement

LOS ANGELES CITYWIDE HISTORIC CONTEXT STATEMENT Context: Filipino Americans in Los Angeles, 1903-1980 Prepared for: City of Los Angeles Department of City Planning Office of Historic Resources August 2018 National Park Service, Department of the Interior Grant Disclaimer This material is based upon work assisted by a grant from the Historic Preservation Fund, National Park Service, Department of the Interior. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of the Interior. SurveyLA Citywide Historic Context Statement Filipino Americans in Los Angeles, 1903-1980 TABLE OF CONTENTS PURPOSE AND SCOPE 1 CONTRIBUTORS 1 PREFACE 2 HISTORIC CONTEXT 10 Introduction 10 Terms and Definitions 10 Beginnings, 1898-1903 11 Early Filipino Immigration to Southern California, 1903-1923 12 Filipino Settlement in Los Angeles: Establishing a Community, 1924-1945 16 Post-World War II and Maturing of the Community, 1946-1964 31 Filipino American Los Angeles, 1965-1980 42 ASSOCIATED PROPERTY TYPES AND ELIGIBILITY REQUIREMENTS 49 BIBLIOGRAPHY 73 APPENDICES: Appendix A: Filipino American Known and Designated Resources Appendix B: SurveyLA’s Asian American Historic Context Statement Advisory Committee SurveyLA Citywide Historic Context Statement Filipino Americans in Los Angeles, 1903-1980 PURPOSE AND SCOPE In 2016, the City of Los Angeles Office of Historic Resources (OHR) received an Underrepresented Communities grant from the National Park Service to develop a National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form (MPDF) and associated historic contexts for five Asian American communities in Los Angeles: Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Thai, and Filipino. -

Exploring the Development Trend of Chinese Education in the Tertiary Level (Philippines)

EXPLORING THE DEVELOPMENT TREND OF CHINESE EDUCATION IN THE TERTIARY LEVEL (PHILIPPINES) PROF. DAISY CHENG SEE ABSTRACT This paper traces the changes and developments in Chinese education in the Philippines by a survey of the history thereof. It discusses how Chinese education developed from an education catered to a small number of overseas Chinese to the ethnic Chinese, from an education of students of Chinese descent to mainstream Philippine society in the tertiary level, and the role played by the socio-political environment in this regard. This paper also seeks to answer the question of whether the policy of the Philippine government has anything to do with this development. Difficulties and obstacles to this type of education are discussed. Through an evaluation of the foregoing, this paper proposes some solutions to the perceived problems. This paper uses the investigative exploratory method of study. Books and relevant publications are utilized where necessary. Materials from the Internet from recognized institutions are also used as reference. Interviews and surveys were also conducted in the process of this study. Keywords: Mandarin Linguistic routines; Digital storytelling, Communicative Approach CHINESE STUDIES PROGRAM LECTURE SERIES © Ateneo de Manila University No. 3, 2016: 56–103 http://journals.ateneo.edu SEE / DEVELOPMENT TREND OF CHINESE EDUCATION 57 hinese education in the Philippines refers to the education C taught to ethnic Chinese who became Filipino citizens in Chinese schools after Filipinization.1 Chinese schools have already systematically turned into private Filipino schools that taught the Chinese language (Constitution of the Philippines, 1973).2 Basically, this so-called “Chinese-Filipino education” must have begun in 1976, when Chinese schools in the Philippines underwent comprehensive Filipinization. -

THE LIFE and TIMES of CARLOS BULOSAN a Thesis

KAIN NA! THE LIFE AND TIMES OF CARLOS BULOSAN A Thesis Presented to the faculty of the Department of History California State University, Sacramento Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History by Donald Estrella Piring, Jr. FALL 2016 © 2016 Donald Estrella Piring, Jr. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii Preface This thesis, Kain Na!, began as a project in Fall 2015.1 It was based on a historic community of Filipino migrant workers and shopkeepers – Little Manila in Stockton, California. America’s legalized racism and American citizens’ individual prejudices segregated Asian migrant workers to designated districts, one of which was Stockton’s Little Manila. The immigrants were expressly forbidden from leaving these districts, except for work or out-of-town travel. The history of just one community is too broad for one paper, and so the project was repurposed to examine just one individual – Allos “Carlos” Bulosan, Filipino writer and labor organizer. There are some limitations to the study. Attempts were made to contact Dr. Dawn Mabalon at San Francisco State University and Conor M. Casey at the University of Washington, Seattle. Most of the materials consulted during the Fall 2015 semester were fiction and prose written by Bulosan. One year later, archival materials were consulted and this thesis was written. There was insufficient time to reread all the materials with new evidence and insights. Not all of the known Bulosan materials (in the UW Seattle Special Collections or elsewhere) were examined. Microfilm and audio cassettes were not consulted, lest they become damaged in the research process. -

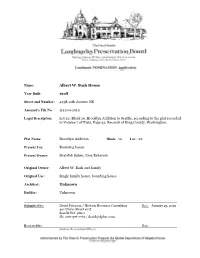

Albert W. Bash House Year Built: 1908 Street and Number

Name: Albert W. Bash House Year Built: 1908 Street and Number: 4238 12th Avenue NE Assessor's File No. 114200-1010 Legal Description: Lot 22, Block 10, Brooklyn Addition to Seattle, according to the plat recorded in Volume 7 of Plats, Page 32, Records of King County, Washington. Plat Name: Brooklyn Addition Block: 10 Lot: 22 Present Use: Rooming house Present Owner: Sharifah Sabah, Lina Baharain Original Owner: Albert W. Bash and family Original Use: Single family house, boarding house Architect: Unknown Builder: Unknown Submitted by: David Peterson / Historic Resource Consulting Date: January 25, 2019 301 Union Street #115 Seattle WA 98111 Ph: 206-376-7761 / [email protected] Reviewed by: Date: (Historic Preservation Officer) Albert W. Bash house 4238 12th Avenue NE Seattle Landmarks Preservation Board January 25, 2019 (revised March 12, 2019) David Peterson historic resource consulting 301 Union Street #115 Seattle WA 98111 P:206-376-7761 [email protected] Albert W. Bash House - 4238 12th Avenue NE Seattle Landmark Nomination INDEX I. Introduction 3 II. Building information 3 III. Architectural description 4 A. Site and neighborhood context B. Building description C. Summary of primary alterations IV. Historical context 7 A. The development of the University District neighborhood B. Building owners and occupants C. The subject property as a rooming house a. Rooming house b. Filipino student house D. Filipino Americans in Seattle E. The American Foursquare house V. Bibliography and sources 21 VI. List of Figures 23 Illustrations 24-55 Site Plan / Survey Following Selected drawings Following David Peterson historic resource consulting – Seattle Landmark Nomination – Albert W. -

Clientproj Draft-Msreview Copy 2

A PROFILE OF THE SMALL BUSINESS COMMUNITY IN HISTORIC FILIPINOTOWN: SEARCH TO INVOLVE PILIPINO AMERICANS A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State Polytechnic University, Pomona In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master In Urban and Regional Planning By Monica Paderanga 2020 SIGNATURE PAGE PROJECT: A PROFILE OF THE SMALL BUSINESS COMMUNITY IN HISTORIC FILIPINOTOWN: SEARCH TO INVOLVE PILIPINO AMERICANS AUTHOR: Monica Paderanga DATE SUBMITTED: Spring 2020 Department of Urban and Regional Planning Dr. Alvaro Huerta _______________________________________ Project Committee Chair Urban and Regional Planning Dr. Annette Koh _______________________________________ Urban and Regional Planning Fidji Victoriano Director of Operations _______________________________________ Search to Involve Pilipino Americans ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Gusto kong isulti salamat sa kong pamilya. Salamat kaayo kong mama ug papa, ug lola. Kung wala ang imonng suporta, dili unta ako makahuman sa pag-eskwela. Genelle ug Megan, dapat kita mahibal-an kung unsaon pagsulti Cebuano aron mapadayon naton nga buhi ang atong kultura. I also want to thank my committee cohort for helping me develop my project, and for motivating me throughout this past year. We might have been caught up in a pandemic, but our drive, energy, and passion for what we do and what we aim to accomplish will help see us through. Thank you to my friends as well for allowing me to share my project with them and for giving me the confidence at times when I needed it most. To my client project committee: Dr. Huerta, Dr. Koh, and Fidji, thank you for being endlessly supportive inside and outside of the classroom. Thank you Fidji for taking me on board to work on this project. -

Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in California, 1850-1970 MPS

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES EVALUATION/RETURN SHEET Requested Action: COVER DOCUMENTATION Multiple Name: Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in California, 1850-1970 MPS State & County: CALIFORNIA, San Francisco Date Received: Date of 45th Day: 11/29/2019 1/13/2020 Reference MC100004867 number: Reason For Review: Checkbox: Unchecked Appeal Checkbox:PDIL Unchecked Checkbox:Text/Data Issue Unchecked Checkbox: Unchecked SHPO Request LandscapeCheckbox: Unchecked PhotoCheckbox: Unchecked Checkbox: Unchecked Waiver Checkbox:National Unchecked Checkbox:Map/Boundary Unchecked Checkbox: Unchecked Resubmission Checkbox:Mobile Resource Unchecked PeriodCheckbox: Unchecked Checkbox:Other Unchecked Checkbox:TCP Unchecked Checkbox:Less than 50 Unchecked years CLGCheckbox: Unchecked Checkbox: Checked Accept ReturnCheckbox: Unchecked Checkbox:Reject Unchecked 1/10/2020 Date Abstract/Summary The Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in California, 1850-1970 MPS cover document is Comments: an excellent resource for the evaluation, documentation and designation of historic ethnic resources in California. The MPS develops three fairly comprehensive thematic contexts and provides registration guidelines for several general and specific property types including historic districts, agricultural properties, industrial sites, community service properties, religious properties and properties associated with significant individuals. Additional contexts, time periods, and associated property types may be developed at a later date. NPS grant funded project. Recommendation/ Accept MPS Cover Documentation Criteria Reviewer Paul Lusignan Discipline Historian Telephone (202)354-2229 Date 1/10/2020 DOCUMENTATION: see attached comments: No see attached SLR: Yes If a nomination is returned to the nomination authority, the nomination is no longer under consideration by the National Park Service. NPS Form 10-900-a (Rev. -

UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Managing the (Post)Colonial : race, gender and sexuality in literary texts of the Philippine Commonwealth Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6px6j526 Author Solomon, Amanda Lee Albaniel Publication Date 2011 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Managing the (Post)Colonial: Race, Gender and Sexuality in Literary Texts of the Philippine Commonwealth A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Literature by Amanda Lee Albaniel Solomon Committee in charge: Professor Rosemary George, Co-Chair Professor John D. Blanco, Co-Chair Professor Yen Le Espiritu Professor Lisa Lowe Professor Meg Wesling 2011 Copyright Amanda Lee Albaniel Solomon, 2011 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Amanda Lee Albaniel Solomon is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ Co-Chair ________________________________________________________________________ Co-Chair University of California, San Diego 2011 iii DEDICATION I dedicate this dissertation to: My parents, Dr. & Mrs. Antonio and Remedios Solomon. This project is the culmination of my attempt to understand their place in America, of my appreciation of all their sacrifices for me and my sister and of my striving to honor their example of always giving back to our community. Everything of value that I have in my life has come from them and I hope I have made them as proud of my efforts as I am of all they have accomplished. -

METROIMPERIAL INTIMACIES PERVERSE MODERNITIES a Series Edited by Jack Halberstam and Lisa Lowe INTIMACIES METROIMPERIAL

METROIMPERIAL INTIMACIES PERVERSE MODERNITIES A Series Edited by Jack Halberstam and Lisa Lowe INTIMACIES METROIMPERIAL FANTASY, RACIAL- SEXUAL GOVERNANCE, AND THE PHILIPPINES IN U.S. IMPERIALISM, 1899–1913 Victor Román Mendoza duke university press Durham and London 2015 © 2015 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Typeset in Minion Pro by Westchester Book group Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Mendoza, Victor Román, [date] author. Metroimperial intimacies : fantasy, racial-sexual governance, and the Philippines in U.S. imperialism, 1899–1913 / Victor Román Mendoza. pages cm—(Perverse modernities) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8223-6019-3 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8223-6034-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8223-7486-2 (e-book) 1. Imperialism—Social aspects—Philippines—History— 20th century. 2. United States—Territories and possessions— History—20th century. 3. Colonial administrators—Philippines— Attitudes—History—20th century. 4. United States—Foreign relations—Philippines. 5. Philippines—Foreign relations—United States. I. Title. II. Series: Perverse modernities. E183.8.P6M46 2015 327.7305990904—dc23 2015022771 Cover art: Philippines, May 3, 1898; Everett Collection Inc. / Alamy. Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the University of Michigan College of Literature, Science, and Arts and the University of Michigan Office of Research, which provided funds toward the publication of this book. For PKB This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS ix Ac know ledg ments 1 INTRODUCTION 35 CHAPTER 1 Racial- Sexual Governance and the U.S. Colonial State in the Philippines 63 CHAPTER 2 Unmentionable Liberties: A Racial- Sexual Differend in the U.S. -

Filipino American Union and Community Organizing in Seattle in the 1970S

Building a Movement: Filipino American Union and Community Organizing in Seattle in the 1970s by Ligaya Rene Domingo A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Catherine Ceniza Choy, Co-Chair Professor Ingrid Seyer-Ochi, Co-Chair Professor Zeus Leonardo Professor Kim Voss Spring 2010 Building a Movement: Filipino American Union and Community Organizing in Seattle in the 1970s 2010 by Ligaya Rene Domingo 1 Abstract Building a Movement: Filipino American Union and Community Organizing in Seattle in the 1970s by Ligaya Rene Domingo Doctor of Philosophy in Education University of California, Berkeley Professor Catherine Ceniza Choy, Co-Chair Professor Ingrid Seyer-Ochi, Co-Chair The Asian American Movement emerged in the late 1960s and early 1970s inspired by the Civil Rights Movement, Antiwar Movement, Black Liberation Movement, and struggles for liberation in Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East. Activists, including college students and community members throughout the United States, used “mass line” tactics to raise political awareness, build organizations, address community concerns, and ultimately to serve their communities. While the history of the Asian American Movement has been chronicled, the scholarship has been analytically and theoretically insufficient -and in some cases nonexistent- in terms of local struggles, how the movement unfolded, and the role of Filipino Americans. This dissertation focuses on one, untold story of the Asian American Movement: the role of activists in Seattle, Washington who were concerned with regional injustices affecting Filipino Americans. -

ESGUERRA Dissertation FINAL 9 23 2013

Interracial Romances of American Empire: Migration, Marriage, and Law in Twentieth Century California by Maria Paz Gutierrez Esguerra A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in the University of Michigan 2013 Doctoral Committee: Professor Scott Kurashige, Chair Professor Martha Jones Assistant Professor Victor Mendoza Professor Tiya Miles Professor Penny Von Eschen © Maria Paz Gutierrez Esguerra 2013 This is dedicated to my parents: Juan Valencia Esguerra, Jr. and Luz Gutierrez Esguerra for their endless love and support. ii Acknowledgements This has been an incredible journey and I am so grateful to have had the opportunity to spend my time at the University of Michigan doing what I love best with the support of so many. This project would not have been possible without the support of many colleagues, family, friends, institutions, mentors, and teachers. At the University of Michigan, I would like to thank my committee: Scott Kurashige, Martha Jones, Victor Mendoza, Tiya Miles, and Penny Von Eschen who believed in this project well before I could even envision it on my own. I am indebted to my advisor Scott Kurashige who has done so much to help me and encourage me throughout this whole journey so that I could reach this incredible milestone. Martha Jones encouraged my enthusiasm for Critical Race Studies and helped frame my thinking of race and the law in new ways. Victor Mendoza, for his unwavering support of my work and professional development. I also extend my appreciation to Tiya Miles who has been a wonderful teacher and mentor. -

Physical Characteristics of the Philippines

From the ‘Pearl of the Orient’ Language and Culture THE LURE OF ADVENTURE IN A FOREIGN LAND • TAGALOG is the country’s national language. Literally, it brought many Filipinos to the United States of America. How- means “People of the River” (Taga-ilog) as early Manila City ever, most came for job opportunities and improved livelihood. was built along Pasig River. • a member of the Malayo-Polynesian family of languages IMMIGRATION BEGAN early in North American history: • also called “Pilipino” and spoken in south of Central Luzon • First recorded Filipino landed in America in 1587 on the • ENGLISH is the language of business, government and education California Coast, with Spanish explorer Pedro de Unamuno • with Tagalog, it is taught in elementary and high school • 1763: Filipinos settled in Louisiana after jumping ship from • spoken by most people throughout the islands Spanish galleons plying trade routes between Manila and • 87 dialects are spoken in the Philippines Acapulco. Known as Filipino Cajun or Manila Men, they developed shrimp and fish drying industry in Louisiana CULTURAL CHARACTERISTICS have been influenced by • 1903-1905: First wave of immigration: approximately 500 the Chinese, Malayan, Spanish, and American cultures and are students called “Pensionados” evident in the unique Filipino society: • supported by U.S. government through Pensionado Act of • gestures common in United States are also common to 1903 under administration of William Taft, Civil Gover- Filipinos, however, beckoning is done by waving all fingers nor