Exploring the Development Trend of Chinese Education in the Tertiary Level (Philippines)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 Integrated Annual Corporate Governance Report

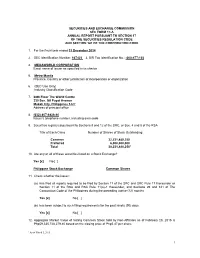

Secutitieg aner Exchonge NIsvto Commission @\ SEC FORM _ I-ACGR INTEGRATED ANNUAT CORPORATE GOVERNANCE REPORT t. For the fiscal year ended: December 3 1. 20 1 7 2. SEC Identification Number: PW-686 3. BIR Tax Identification No.: 000-263-340 4. Exact name of issuer as specified in its charter: PHILIPPINE BANK 0F COMMUNICATIONS 5, Philippines (SEC Use Only) Province, Country or otherjurisdiction of Industrv Classification Code: incorporation or organization 7, 7226 Address ofprincipal office Postal Code 8, 830-7000 Issuer's telephone number, including area code 9. NA Former name, former address, and former fiscal year, if changed since last report. * SEC Form - I-ACGR Uodated 21,Dec2OI7 Page 3 of 80 INTEGRATED ANNUAL CORPORATE GOVERNANCE REPORT RECOMMENDED CG COMPLIANT ADDITIONAL INFORMATION EXPLANATION PRACTICE/POLICY / NON- COMPLIANT The Board’s Governance Responsibilities Principle 1: The company should be headed by a competent, working board to foster the long- term success of the corporation, and to sustain its competitiveness and profitability in a manner consistent with its corporate objectives and the long- term best interests of its shareholders and other stakeholders. Recommendation 1.1 1. Board is composed of directors Compliant • Eric O. Recto – Chairman of the Board & Director with collective working Mr. Recto, Filipino, 54 years old, was elected Director and Vice Chairman of the knowledge, experience or Board on July 26, 2011, appointed Co-Chairman of the Board on January 18, 2012 expertise that is relevant to the and Chairman of the Board on May 23, 2012. He is the Chairman and CEO of ISM company’s industry/sector. -

Masterlist of Private Schools Sy 2011-2012

Legend: P - Preschool E - Elementary S - Secondary MASTERLIST OF PRIVATE SCHOOLS SY 2011-2012 MANILA A D D R E S S LEVEL SCHOOL NAME SCHOOL HEAD POSITION TELEPHONE NO. No. / Street Barangay Municipality / City PES 1 4th Watch Maranatha Christian Academy 1700 Ibarra St., cor. Makiling St., Sampaloc 492 Manila Dr. Leticia S. Ferriol Directress 732-40-98 PES 2 Adamson University 900 San Marcelino St., Ermita 660 Manila Dr. Luvimi L. Casihan, Ph.D Principal 524-20-11 loc. 108 ES 3 Aguinaldo International School 1113-1117 San Marcelino St., cor. Gonzales St., Ermita Manila Dr. Jose Paulo A. Campus Administrator 521-27-10 loc 5414 PE 4 Aim Christian Learning Center 507 F.T. Dalupan St., Sampaloc Manila Mr. Frederick M. Dechavez Administrator 736-73-29 P 5 Angels Are We Learning Center 499 Altura St., Sta. Mesa Manila Ms. Eva Aquino Dizon Directress 715-87-38 / 780-34-08 P 6 Angels Home Learning Center 2790 Juan Luna St., Gagalangin, Tondo Manila Ms. Judith M. Gonzales Administrator 255-29-30 / 256-23-10 PE 7 Angels of Hope Academy, Inc. (Angels of Hope School of Knowledge) 2339 E. Rodriguez cor. Nava Sts, Balut, Tondo Manila Mr. Jose Pablo Principal PES 8 Arellano University (Juan Sumulong campus) 2600 Legarda St., Sampaloc 410 Manila Mrs. Victoria D. Triviño Principal 734-73-71 loc. 216 PE 9 Asuncion Learning Center 1018 Asuncion St., Tondo 1 Manila Mr. Herminio C. Sy Administrator 247-28-59 PE 10 Bethel Lutheran School 2308 Almeda St., Tondo 224 Manila Ms. Thelma I. Quilala Principal 254-14-86 / 255-92-62 P 11 Blaze Montessori 2310 Crisolita Street, San Andres Manila Ms. -

Redalyc.Filipinos in the U.S.: Historical, Social, and Educational

Social and Education History E-ISSN: 2014-3567 [email protected] Hipatia Press España Paik, Susan J.; Mamaril Choe, Shirlie Mae; Witenstein, Matthew A. Filipinos in the U.S.: Historical, Social, and Educational Experiences Social and Education History, vol. 5, núm. 2, junio, 2016, pp. 134-160 Hipatia Press Barcelona, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=317046062002 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Instructions for authors, subscriptions and further details: http://hse.hipatiapress.com Filipinos in the U.S.: Historical, Social, and Educational Experiences Susan J. Paik1, Shirlie Mae Mamaril Choe1, Matthew A. Witenstein2 1) Claremont Graduate University (USA) 2) University of San Diego (USA) Date of publication: June 23rd, 2016 Edition period: June 2016 – October 2016 To cite this article: Paik, S.J., Choe, S.M.M., & Witenstein, M.A. (2016). Filipinos in the U.S.: Historical, Social, and Educational Experiences. Social and Education History 5(2), 134-160. doi:10.17583/hse.2016.2062 To link this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.17583/hse.2016.2062 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE The terms and conditions of use are related to the Open Journal System and to Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY). HSE – Social and Education History Vol. 5 No. 2 June 2016 pp.134- 160 Filipinos in the U.S.: Historical, Social, and Educational Experiences Susan J. -

Filipino Americans in Los Angeles Historic Context Statement

LOS ANGELES CITYWIDE HISTORIC CONTEXT STATEMENT Context: Filipino Americans in Los Angeles, 1903-1980 Prepared for: City of Los Angeles Department of City Planning Office of Historic Resources August 2018 National Park Service, Department of the Interior Grant Disclaimer This material is based upon work assisted by a grant from the Historic Preservation Fund, National Park Service, Department of the Interior. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of the Interior. SurveyLA Citywide Historic Context Statement Filipino Americans in Los Angeles, 1903-1980 TABLE OF CONTENTS PURPOSE AND SCOPE 1 CONTRIBUTORS 1 PREFACE 2 HISTORIC CONTEXT 10 Introduction 10 Terms and Definitions 10 Beginnings, 1898-1903 11 Early Filipino Immigration to Southern California, 1903-1923 12 Filipino Settlement in Los Angeles: Establishing a Community, 1924-1945 16 Post-World War II and Maturing of the Community, 1946-1964 31 Filipino American Los Angeles, 1965-1980 42 ASSOCIATED PROPERTY TYPES AND ELIGIBILITY REQUIREMENTS 49 BIBLIOGRAPHY 73 APPENDICES: Appendix A: Filipino American Known and Designated Resources Appendix B: SurveyLA’s Asian American Historic Context Statement Advisory Committee SurveyLA Citywide Historic Context Statement Filipino Americans in Los Angeles, 1903-1980 PURPOSE AND SCOPE In 2016, the City of Los Angeles Office of Historic Resources (OHR) received an Underrepresented Communities grant from the National Park Service to develop a National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form (MPDF) and associated historic contexts for five Asian American communities in Los Angeles: Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Thai, and Filipino. -

1 Securities and Exchange Commission Sec Form 17-A

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION SEC FORM 17-A ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 17 OF THE SECURITIES REGULATION CODE AND SECTION 141 OF THE CORPORATION CODE 1. For the fiscal year ended 31 December 2014 2. SEC Identification Number: 167423 3. BIR Tax Identification No.: -000-477-103 4. MEGAWORLD CORPORATION Exact name of issuer as specified in its charter 5. Metro Manila Province, Country or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization 6. (SEC Use Only) Industry Classification Code 7. 28th Floor The World Centre 330 Sen. Gil Puyat Avenue Makati City, Philippines 1227 Address of principal office 8. (632) 867-8826-40 Issuer’s telephone number, including area code 9. Securities registered pursuant to Sections 8 and 12 of the SRC, or Sec. 4 and 8 of the RSA Title of Each Class Number of Shares of Stock Outstanding Common 32,231,480,250 Preferred 6,000,000,000 Total 38,231,480,2501 10. Are any or all of these securities listed on a Stock Exchange? Yes [x] No [ ] Philippine Stock Exchange Common Shares 11. Check whether the issuer: (a) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 17 of the SRC and SRC Rule 17 thereunder or Section 11 of the RSA and RSA Rule 11(a)-1 thereunder, and Sections 26 and 141 of The Corporation Code of the Philippines during the preceding twelve (12) months. Yes [x] No [ ] (b) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past ninety (90) days. Yes [x] No [ ] 12. Aggregate Market Value of Voting Common Stock held by Non-Affiliates as of February 28, 2015 is Php59,335,728,279.40 based on the closing price of Php5.47 per share. -

Philippine Bank of Communications (PBCOM) Reported a Consolidated Net Income of Php1.17B in 2020

BANKING TABLE OF CONTENTS IN THE NEW About the Cover 1 NORMAL PBCOM Through the Years 2 Our Vision, Mission and Values 3 Chairman’s Message 4 The President Speaks 6 ABOUT THE COVER Banking in the New Normal 10 With a health crisis threatening the world, 2020 was a Our Board of Directors 15 year of challenges for many. A lot of changes had to be Our Senior Management Team 24 made in order to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic. For financial institutions such as PBCOM, the challenge is to Our Business 32 continuously provide the necessary financial services to Our Branch and ATM Network 35 the public without compromising the health and safety of both our employees and the banking public. Sustainability Report 43 Corporate Governance 60 This annual report highlights the successes that PBCOM achieved in 2020 in meeting these challenges. Risk and Capital Management 75 Investments in digital capabilities, product Consumer Protection and Experience 93 enhancements, improvements in service delivery, and the implementation of operational changes, are only Financial Highlights 98 some of the major steps we undertook in order to deliver a superior banking experience in the new normal. 1 Our bank, PBCOM, has a very rich history marked by a legacy of strong relationships nurtured through trust and service. And our thrust to focus on you, our clients, is always the center of everything we do. In 2020, we continue our journey towards building a “digital-first” banking experience for our clients. We have formally launched PBCOMobile, the Bank’s all-mobile banking platform to enhance our other digital offerings. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 99 3rd International Conference on Social Science and Higher Education (ICSSHE-17) The Strategies of the Popularization of Mandarin Chinese in the Philippines under the New Sino- Philippine Relations Lili Xu Dehui Li The Southern Base of Confucius Institute Headquarters, College of Foreign language and Cultures, Xiamen University Xiamen University Xiamen, China Xiamen, China [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—At present, the popularization of Mandarin there are 167 Philippine Chinese schools(PCS), most of which Chinese (PMC) in the Philippines are facing some problems, such have established courses from kindergarten to middle school. as low effectiveness of class teaching, the obstruction from the mainstream society, fierce competition with other foreign Since the 1990s, conforming to the trend of times, PCS and languages. This article tries to provide some specific suggestions CLE institutes have been exploring new methods on internal on the teaching subjects, contents, channels, and layout mechanism, teaching methodology and international exchanges, considering the analysis of the history and status quo of PMC in which brought in more students coming for schooling. this area. “Students of Chinese descendants are not the only group in schools, the ratio of non-Chinese is still in the rise.”2 On 10th Keywords—Philippines; popularization of Mandarin Chinese; April 2016, the 2nd Summit Conference for the Philippine Sino-Philippine relations; diversification Chinese School hosted by the Tan Yankui Fund and the Center for Chinese Language Education in the Philippines was held in I. INTRODUCTION Manila. Representatives of 96 Chinese schools have come to a The Philippines is located in southeastern Asia and is an new resolution----Carrying Forward CLE Spirit and composing important neighbor of China. -

Copyright by Shannon Guillot-Wright 2018

Copyright by Shannon Guillot-Wright 2018 The Dissertation Committee for Shannon Guillot-Wright Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Casting Aside Bent Bodies: Embodied Violence as an Everyday Experience for Filipino Migrant Seafarers Committee: Arlene Macdonald, PhD, Supervisor and Chair Rebecca Hester, PhD, Mentor and Co-Chair Jerome Crowder, PhD Premal Patel, MD William Terry, PhD _______________________________ David W. Niesel, PhD Dean, Graduate School Casting Aside Bent Bodies: Embodied Violence as an Everyday Experience for Filipino Migrant Seafarers by Shannon Guillot-Wright, MA Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas Medical Branch in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Medical Humanities The University of Texas Medical Branch November, 2018 Dedication “In the book there will be no dedication (for I can’t give you what has been yours from the beginning) but instead: From the property of…” –Rainer Marie Rilke, Duino Elegies From the property of: The men and women who live and work at sea Acknowledgements I am grateful to the Institute for the Medical Humanities and the Center to Eliminate Health Disparities for financial and intellectual support in the form of assistantships, scholarships, and fellowships. I am also thankful to the Harry Huntt Ransom Dissertation Fellowship Award in the Medical Humanities and the Chester R. Burns Institute for the Medical Humanities Alumni Award for helping to make this research richer, and to the John P. McGovern Academy of Oslerian Medicine for making the photovoice project and gallery showing possible. -

Megaworld Corporation 3

CR04055-2017 SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION SEC FORM ACGR ANNUAL CORPORATE GOVERNANCE REPORT 1. Report is Filed for the Year Dec 31, 2016 2. Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in its Charter MEGAWORLD CORPORATION 3. Address of principal office 28th Floor, The World Centre, 330 Sen. Gil Puyat Avenue, Makati City Postal Code 1227 4.SEC Identification Number 167423 5. Industry Classification Code(SEC Use Only) 6. BIR Tax Identification No. 000-477-103 7. Issuer's telephone number, including area code (632) 867-8826 to 40 8. Former name or former address, if changed from the last report N/A The Exchange does not warrant and holds no responsibility for the veracity of the facts and representations contained in all corporate disclosures, including financial reports. All data contained herein are prepared and submitted by the disclosing party to the Exchange, and are disseminated solely for purposes of information. Any questions on the data contained herein should be addressed directly to the Corporate Information Officer of the disclosing party. Megaworld Corporation MEG PSE Disclosure Form ACGR-1 - Annual Corporate Governance Report Reference: Revised Code of Corporate Governance of the Securities and Exchange Commission Description of the Disclosure In compliance with SEC Memorandum Circular No. 20 series of 2016, attached herewith is the Annual Corporate Governance Report (SEC Form-ACGR) of Megaworld Corporation for the year 2016. Filed on behalf by: Name Dohrie Edangalino Designation Head-Corporate Compliance Group MEGAWORLD CORPORATION ANNUAL CORPORATE GOVERNANCE REPORT (SEC FORM – ACGR) FOR YEAR 2016 SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION SEC FORM – ACGR ANNUAL CORPORATE GOVERNANCE REPORT 1. -

Downloadable Annual Report Yes

CR02058-2016 SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION SEC FORM 17-A, AS AMENDED ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 17 OF THE SECURITIES REGULATION CODE AND SECTION 141 OF THE CORPORATION CODE OF THE PHILIPPINES 1. For the fiscal year ended Dec 31, 2015 2. SEC Identification Number 167423 3. BIR Tax Identification No. 000-477-103 4. Exact name of issuer as specified in its charter MEGAWORLD CORPORATION 5. Province, country or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization Metro Manila 6. Industry Classification Code(SEC Use Only) 7. Address of principal office 28th Floor, The World Centre, 330 Sen. Gil Puyat Avenue, Makati City Postal Code 1227 8. Issuer's telephone number, including area code (632) 8678826 to 40 9. Former name or former address, and former fiscal year, if changed since last report N/A 10. Securities registered pursuant to Sections 8 and 12 of the SRC or Sections 4 and 8 of the RSA Title of Each Class Number of Shares of Common Stock Outstanding and Amount of Debt Outstanding Common 32,239,445,872 Preferred 6,000,000,000 11. Are any or all of registrant's securities listed on a Stock Exchange? Yes No If yes, state the name of such stock exchange and the classes of securities listed therein: Philippine Stock Exchange, Common Shares 12. Check whether the issuer: (a) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 17 of the SRC and SRC Rule 17.1 thereunder or Section 11 of the RSA and RSA Rule 11(a)-1 thereunder, and Sections 26 and 141 of The Corporation Code of the Philippines during the preceding twelve (12) months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports) Yes No (b) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past ninety (90) days Yes No 13. -

THE LIFE and TIMES of CARLOS BULOSAN a Thesis

KAIN NA! THE LIFE AND TIMES OF CARLOS BULOSAN A Thesis Presented to the faculty of the Department of History California State University, Sacramento Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History by Donald Estrella Piring, Jr. FALL 2016 © 2016 Donald Estrella Piring, Jr. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii Preface This thesis, Kain Na!, began as a project in Fall 2015.1 It was based on a historic community of Filipino migrant workers and shopkeepers – Little Manila in Stockton, California. America’s legalized racism and American citizens’ individual prejudices segregated Asian migrant workers to designated districts, one of which was Stockton’s Little Manila. The immigrants were expressly forbidden from leaving these districts, except for work or out-of-town travel. The history of just one community is too broad for one paper, and so the project was repurposed to examine just one individual – Allos “Carlos” Bulosan, Filipino writer and labor organizer. There are some limitations to the study. Attempts were made to contact Dr. Dawn Mabalon at San Francisco State University and Conor M. Casey at the University of Washington, Seattle. Most of the materials consulted during the Fall 2015 semester were fiction and prose written by Bulosan. One year later, archival materials were consulted and this thesis was written. There was insufficient time to reread all the materials with new evidence and insights. Not all of the known Bulosan materials (in the UW Seattle Special Collections or elsewhere) were examined. Microfilm and audio cassettes were not consulted, lest they become damaged in the research process. -

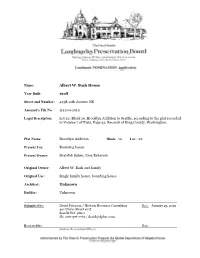

Albert W. Bash House Year Built: 1908 Street and Number

Name: Albert W. Bash House Year Built: 1908 Street and Number: 4238 12th Avenue NE Assessor's File No. 114200-1010 Legal Description: Lot 22, Block 10, Brooklyn Addition to Seattle, according to the plat recorded in Volume 7 of Plats, Page 32, Records of King County, Washington. Plat Name: Brooklyn Addition Block: 10 Lot: 22 Present Use: Rooming house Present Owner: Sharifah Sabah, Lina Baharain Original Owner: Albert W. Bash and family Original Use: Single family house, boarding house Architect: Unknown Builder: Unknown Submitted by: David Peterson / Historic Resource Consulting Date: January 25, 2019 301 Union Street #115 Seattle WA 98111 Ph: 206-376-7761 / [email protected] Reviewed by: Date: (Historic Preservation Officer) Albert W. Bash house 4238 12th Avenue NE Seattle Landmarks Preservation Board January 25, 2019 (revised March 12, 2019) David Peterson historic resource consulting 301 Union Street #115 Seattle WA 98111 P:206-376-7761 [email protected] Albert W. Bash House - 4238 12th Avenue NE Seattle Landmark Nomination INDEX I. Introduction 3 II. Building information 3 III. Architectural description 4 A. Site and neighborhood context B. Building description C. Summary of primary alterations IV. Historical context 7 A. The development of the University District neighborhood B. Building owners and occupants C. The subject property as a rooming house a. Rooming house b. Filipino student house D. Filipino Americans in Seattle E. The American Foursquare house V. Bibliography and sources 21 VI. List of Figures 23 Illustrations 24-55 Site Plan / Survey Following Selected drawings Following David Peterson historic resource consulting – Seattle Landmark Nomination – Albert W.