Downloaded from Brill.Com09/27/2021 03:11:54PM Via Free Access 26 in Search of a Path Stopped Its Payments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Desi Bouterse Van Autoritair-Populistisch Leider Naar Charismatisch-Populistisch Leider

Desi Bouterse Van autoritair-populistisch leider naar charismatisch-populistisch leider Reineke Maschhaupt Scriptie Master History of European Expansion and Globalisation Begeleider: Peter Meel Inhoudsopgave Inleiding 1 Charisma en populisme in het Caribisch gebied 2 Hoofdstuk 1 Charisma Wat is charisma? 4 Puur en routinised charisma 5 Charisma en religiositeit 6 Hoofdstuk 2 Populisme 7 Zes sleutelthema’s Hoofdstuk 3 Charisma en populisme 9 Hoofdstuk 4 Context Suriname Voedingsbodem Economische verstoring 10 De economische ontwikkelingen tot 1980 11 Emigratie 12 Het politieke systeem 12 De etnische politieke uitdaging 13 Surinaams leger 15 Politieke spanningen 15 Spanningen lopen op tot hoogtepunt 16 Voedingsbodem 17 Hoofdstuk 5 1980 - 1987 Militair regime Jeugd Bouterse 19 Ontevreden militairen 19 ‘Stelletje padvinders’ 20 Tegen wil en dank in aan de macht gekomen 21 Drie coup-plannen 21 Opgewonden sfeer 22 ´Onze jongens´ 22 Supreme caudillo 23 Maatregelen tegen de oude rotten 23 Crisis? 24 Vernieuwing? 24 Te volgen ideologie 24 Kameleon 25 China a Sen president van de burgerregering 26 De ruziemakers grijpen hun kans 27 Bouterse ontpopt zich als leider 27 Toch revolutie 28 Andere spelregels 28 Militaire dictatuur 29 Heartland 30 Achterdocht 31 Groeiende oppositie 32 Onder invloed van Maurice Bishop 32 De nacht van 7 op 8 december 33 Nieuwe orde = Nieuwe elite? 34 Geen weg terug 34 Lijfsbehoud of revolutie? 35 Bouterse krabbelt terug 35 Terug naar democratie? 36 Charisma ? 36 Hoofdstuk 6 1987 - 2000 Van militair naar democraat Imagoschade -

363 Part 238—Contracts With

Immigration and Naturalization Service, Justice § 238.3 (2) The country where the alien was mented on Form I±420. The contracts born; with transportation lines referred to in (3) The country where the alien has a section 238(c) of the Act shall be made residence; or by the Commissioner on behalf of the (4) Any country willing to accept the government and shall be documented alien. on Form I±426. The contracts with (c) Contiguous territory and adjacent transportation lines desiring their pas- islands. Any alien ordered excluded who sengers to be preinspected at places boarded an aircraft or vessel in foreign outside the United States shall be contiguous territory or in any adjacent made by the Commissioner on behalf of island shall be deported to such foreign the government and shall be docu- contiguous territory or adjacent island mented on Form I±425; except that con- if the alien is a native, citizen, subject, tracts for irregularly operated charter or national of such foreign contiguous flights may be entered into by the Ex- territory or adjacent island, or if the ecutive Associate Commissioner for alien has a residence in such foreign Operations or an Immigration Officer contiguous territory or adjacent is- designated by the Executive Associate land. Otherwise, the alien shall be de- Commissioner for Operations and hav- ported, in the first instance, to the ing jurisdiction over the location country in which is located the port at where the inspection will take place. which the alien embarked for such for- [57 FR 59907, Dec. 17, 1992] eign contiguous territory or adjacent island. -

Airlines Prefix Codes 1

AMERICAN AIRLINES,INC (AMERICAN EAGLE) UNITED STATES 001 0028 AA AAL CONTINENTAL AIRLINES (CONTINENTAL EXPRESS) UNITED STATES 005 0115 CO COA DELTA AIRLINES (DELTA CONNECTION) UNITED STATES 006 0128 DL DAL NORTHWEST AIRLINES, INC. (NORTHWEST AIRLINK) UNITED STATES 012 0266 NW NWA AIR CANADA CANADA 014 5100 AC ACA TRANS WORLD AIRLINES INC. (TRANS WORLD EXPRESS) UNITED STATES 015 0400 TW TWA UNITED AIR LINES,INC (UNITED EXPRESS) UNITED STATES 016 0428 UA UAL CANADIAN AIRLINES INTERNATIONAL LTD. CANADA 018 2405 CP CDN LUFTHANSA CARGO AG GERMANY 020 7063 LH GEC FEDERAL EXPRESS (FEDEX) UNITED STATES 023 0151 FX FDX ALASKA AIRLINES, INC. UNITED STATES 027 0058 AS ASA MILLON AIR UNITED STATES 034 0555 OX OXO US AIRWAYS INC. UNITED STATES 037 5532 US USA VARIG S.A. BRAZIL 042 4758 RG VRG HONG KONG DRAGON AIRLINES LIMITED HONG KONG 043 7073 KA HDA AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS ARGENTINA 044 1058 AR ARG LAN-LINEA AEREA NACIONAL-CHILE S.A. CHILE 045 3708 LA LAN TAP AIR PORTUGAL PORTUGAL 047 5324 TP TAP CYPRUS AIRWAYS, LTD. CYPRUS 048 5381 CY CYP OLYMPIC AIRWAYS GREECE 050 4274 OA OAL LLOYD AEREO BOLIVIANO S.A. BOLIVIA 051 4054 LB LLB AER LINGUS LIMITED P.L.C. IRELAND 053 1254 EI EIN ALITALIA LINEE AEREE ITALIANE ITALY 055 1854 AZ AZA CYPRUS TURKISH AIRLINES LTD. CO. CYPRUS 056 5999 YVK AIR FRANCE FRANCE 057 2607 AF AFR INDIAN AIRLINES INDIA 058 7009 IC IAC AIR SEYCHELLES UNITED KINGDOM 061 7059 HM SEY AIR CALEDONIE INTERNATIONAL NEW CALEDONIA 063 4465 SB ACI CZECHOSLOVAK AIRLINES CZECHOSLAVAKIA 064 2432 OK CSA SAUDI ARABIAN AIRLINES SAUDI ARABIA 065 4650 SV SVA AIR MOOREA FRENCH POLYNESIA 067 4832 QE TAH LAM-LINHAS AEREAS DE MOCAMBIQUE MOZAMBIQUE 068 7119 TM LAM SYRIAN ARAB AIRLINES SYRIA 070 7127 RB SYR ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES ENTERPRISE ETHIOPIA 071 3224 ET ETH GULF AIR COMPANY G.S.C. -

De Backpackersgids Voor Suriname

De backpackersgids voor Suriname © 2003 | Ferry Bounin | Utrecht DebackpackersgidsvoorSuriname FootprintTravel.nl Inhoud Voorwoord ...................................................................................................................................................... 3 Gebruiksaanwijzing ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Deel I: Algemene en Praktische Informatie .................................................................................................... 6 Hoofdstuk 1 Algemene Informatie ........................................................................................................... 7 1.1 Klimaat .......................................................................................................................................... 7 1.2 Bevolking ...................................................................................................................................... 7 1.3 Taal ................................................................................................................................................ 8 1.3 Religie ........................................................................................................................................... 9 1.4 Politiek ........................................................................................................................................... 9 Hoofdstuk 2 Praktische Informatie ........................................................................................................ -

Roger Janssen

ROGER JANSSEN In search of a path In search ROGER JANSSEN ROGER JANSSEN 1975 to 1991 policy of Suriname from An analysis of the foreign In search of a path An analysis of the foreign policy of Suriname from 1975 to 1991 In search The foreign policy of small states is an often neglected topic, which is particularly the case when it comes to Suriname. How did the young Republic deal with its dependency on the Netherlands for development aid after 1975? Was Paramaribo following a certain foreign policy strategy of a path or did it merely react towards internal and external events? What were the decision making processes in defi ning the foreign policy course and who was involved in these processes? And why was a proposal An analysis of the foreign policy discussed to hand back the right of an independent foreign and defence policy to a Dutch Commonwealth government in the early 1990s? of Suriname from 1975 to 1991 These questions are examined here in depth, in the fi rst comprehensive analysis wof Suriname’s foreign policy from 1975 to 1991. The book provides readers interested in Caribbean and Latin American affairs with a detailed account of Suriname’s external relations. Moreover, the young Republic may stand as a case study, as it confronted the diffi culties and challenges that small developing states often face. Roger Janssen (1967), born in the Dutch-German border region of Cleve, migrated to Australia in 1989. He received his education as a historian at the University of Western Australia where he obtained a Ph.D. -

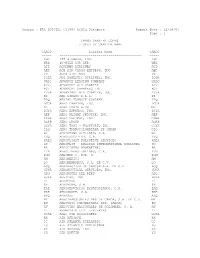

FAA DOT/TSC CY1997 ACAIS Database Report Date : 12/18/97 Page : 1

Source : FAA DOT/TSC CY1997 ACAIS Database Report Date : 12/18/97 Page : 1 CARGO CARRIER CODES LISTED BY CARRIER NAME CARCD Carrier Name CARCD ----- ------------------------------------------ ----- KHC 135 AIRWAYS, INC. KHC WRB 40-MILE AIR LTD. WRB ACD ACADEMY AIRLINES ACD AER ACE AIR CARGO EXPRESS, INC. AER VX ACES AIRLINES VX IQDA ADI DOMESTIC AIRLINES, INC. IQDA UALC ADVANCE LEASING COMPANY UALC ADV ADVANCED AIR CHARTER ADV ACI ADVANCED CHARTERS INT ACI YDVA ADVANTAGE AIR CHARTER, INC. YDVA EI AER LINGUS P.L.C. EI TPQ AERIAL TRANSIT COMPANY TPQ DGCA AERO CHARTER, INC. DGCA ML AERO COSTA RICA ML DJYA AERO EXPRESS, INC. DJYA AEF AERO FLIGHT SERVICE, INC. AEF GSHA AERO FREIGHT, INC. GSHA AGRP AERO GROUP AGRP CGYA AERO TAXI - ROCKFORD, INC. CGYA CLQ AERO TRANSCOLOMBIANA DE CARGA CLQ G3 AEROCHAGO AIRLINES, S.A. G3 EVQ AEROEJECUTIVO, C.A. EVQ XAES AEROFLIGHT EXECUTIVE SERVICES XAES SU AEROFLOT - RUSSIAN INTERNATIONAL AIRLINES SU AR AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS AR LTN AEROLINEAS LATINAS, C.A. LTN ROM AEROMAR C. POR. A. ROM AM AEROMEXICO AM QO AEROMEXPRESS, S.A. DE C.V. QO ACQ AERONAUTICA DE CANCUN S.A. DE C.V. ACQ HUKA AERONAUTICAL SERVICES, INC. HUKA ADQ AERONAVES DEL PERU ADQ HJKA AEROPAK, INC. HJKA PL AEROPERU PL 6P AEROPUMA, S.A. 6P EAE AEROSERVICIOS ECUATORIANOS, C.A. EAE KRE AEROSUCRE, S.A. KRE ASQ AEROSUR ASQ MY AEROTRANSPORTES MAS DE CARGA, S.A. DE C.V. MY ZU AEROVAIS COLOMBIANAS LTD. (ARCA) ZU AV AEROVIAS NACIONALES DE COLOMBIA, S. A. AV ZL AFFRETAIR LTD. (PRIVATE) ZL UCAL AGRO AIR ASSOCIATES UCAL RK AIR AFRIQUE RK CC AIR ATLANTA ICELANDIC CC LU AIR ATLANTIC DOMINICANA LU AX AIR AURORA, INC. -

Regering Ophuneiseningaaten Nomen

VANDAAG * Roven viert als commandant60 jaarVKCp.2 * Willems (KvK) hekelt dienstver- lening van Setel p.3 106E JAARGANG— NO.: 111 VRIJDAG 19 ME11989 Den Dunnen: zuinigheid levert » KLM: miljoenen op p.5 tf Füruns * NSF wil met NOC fuseren p.7 Duarte: honderd geuuondeguer- ist rilla- strijders mogen land uit St Maarten Luft,Hans Grotestoking in Venezuela p.13 RAVEN ...VKC: AMIGOE Hongerstaking Peking ten einde PEKING De hon- in —Chinese stu- eisten een ultimatum dat de tie met een strakke blik opge- gerstakende regering ophuneiseningaaten nomen. denten hebben vrijdag dreigen met een oproep tot al- Zhao maakte een emotionele jjunactie beëindigd. Maar gemene staking in heel China indruk en studenten- leiders heb- deelde handtekenin- oenjje indien de autoriteiten genaan studentenuit. Volgens besloten dat de beto- weigeren. het persagentschap Nieuw Stogen voor meer vrijheid bezoek van ei> Een onverwacht China zei hij: "Wij zijn te laat democratie op het Tia- partijleider Zhao Ziyang en de gekomen. Jullie hebben goede °annien- plein in het premier Li Peng vrijdag in de bedoelingen. Jullie willen dat jjentrumvanPekingzullen vroege ochtend aan de hon- hetbeter gaat metons land. De «joorgaan. Studenten- lei- gerstakende studenten op het problemen die ullienaarvoren riepen hetbesluit per plein van de Hemelse vrede brengen, zullen op één dag zijn 'üidsprekerders op het plein kon hen niet op andere ge- opgelost". om. dachten brengen. Chinese leiding heeft le- Zhao en Li vroegen de stu- INBEDEKTE TERMEN gereenheden in staat van pa- zeven dagen oude De nieuwe verzoenings- po- denten hun ging aatheid gebracht om een ein- ■ Zhao Ziyang actie te staken en verzekerden kwam enkele uren nadat **ete maken aan debetogingen hen dat deregering de dialoog Li de eisen van de studenten van studenten. -

A History of Model League of Nations in the United States

Chapter One _________ A History of Model League of Nations in the United States The origin of intercollegiate simulations of international organizations in the United States can be traced back more than 90 years ago when Australian-born Professor Hessel Duncan Hall of the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs at Syracuse University organized a two-day Model Assembly of the League of Nations on April 29-30, 1927.1 According to Professor Hall, the simulation of the Assembly of the League of Nations was “the first time that a Model League Assembly, participated in by a number of universities, has been held in the United States.”2 The New York Times reported that the precedents of the 1927 Model Assembly of the League of Nations at Syracuse University were similar conferences held previously in Great Britain and Japan.3 According to one report, the Oxford University branch of the League of Nations Union (LNU) organized a “model assembly” of the League of Nations in 1921. Foreign students studying at Oxford University participated in the “model assembly” as representatives of some 34 countries, including Australia and India.4 Another report indicated that thirteen student branches of the Japanese League of Nations Association “conceived the idea of holding in Tokyo a public session of a Model League of Nations” in 1925.5 The purposes of the Model Assembly of the League of Nations held at Syracuse University in 1927 were to “enable American and foreign students in New York State to meet for a frank discussion of urgent problems of international relations” and to “give them an opportunity of seeing in action the most important organization for world cooperation ever established.”6 The League of Nations organization, the predecessor of the modern United Nations (U.N.) organization, was established by the allied powers at the end of the First World War. -

363 Part 238—Contracts with Transportation Lines

Immigration and Naturalization Service, Justice § 238.3 (2) The country where the alien was mented on Form I±420. The contracts born; with transportation lines referred to in (3) The country where the alien has a section 238(c) of the Act shall be made residence; or by the Commissioner on behalf of the (4) Any country willing to accept the government and shall be documented alien. on Form I±426. The contracts with (c) Contiguous territory and adjacent transportation lines desiring their pas- islands. Any alien ordered excluded who sengers to be preinspected at places boarded an aircraft or vessel in foreign outside the United States shall be contiguous territory or in any adjacent made by the Commissioner on behalf of island shall be deported to such foreign the government and shall be docu- contiguous territory or adjacent island mented on Form I±425; except that con- if the alien is a native, citizen, subject, tracts for irregularly operated charter or national of such foreign contiguous flights may be entered into by the Ex- territory or adjacent island, or if the ecutive Associate Commissioner for alien has a residence in such foreign Operations or an Immigration Officer contiguous territory or adjacent is- designated by the Executive Associate land. Otherwise, the alien shall be de- Commissioner for Operations and hav- ported, in the first instance, to the ing jurisdiction over the location country in which is located the port at where the inspection will take place. which the alien embarked for such for- [57 FR 59907, Dec. 17, 1992] eign contiguous territory or adjacent island. -

Caribbean Regional Sustainable Tourism Development Programme

Caribbean Regional Sustainable Tourism Development Programme Project No. 8 ACP RCA 035 FINAL REPORT: CARIBBEAN AIR TRANSPORT STUDY FOR CARIBBEAN TOURISM ORGANISATION - LOT 1 RESEARCH CAPACITY 26July 2006 Caribbean Regional Sustainable Tourism Development Programme Project No. 8 ACP RCA 035 FINAL REPORT: CARIBBEAN AIR TRANSPORT STUDY FOR CARIBBEAN TOURISM ORGANISATION - LOT 1 RESEARCH CAPACITY 26July 2006 © PA Knowledge Limited 2006 PA Consulting Group 123 Buckingham Palace Road Prepared by: Ian Bertrand London SW1W 9SR Air Transportation Tel: +44 20 7730 9000 Consultant Fax: +44 20 7333 5050 www.paconsulting.com Version: 4.0 Caribbean Regional Sustainable Tourism Development Programme 28/7/06 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Executive Summary 1-1 1.1 APPROACH TO THE STUDY 1-2 1.2 SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS 1-3 1.3 INTERNATIONAL ‘OPEN SKIES’ AGREEMENTS 1-4 1.4 INTRA-REGIONAL ‘OPEN SKIES’ 1-5 1.5 STRENGTHENING THE DOMICILE AIRLINES 1-5 2. Introduction 2-1 2.1 OBJECTIVE OF THE STUDY 2-1 2.2 APPROACH TO THE STUDY 2-2 3. Situational Analysis 3-1 3.1 THE CONCEPT OF RISK MITIGATION 3-1 3.2 CURRENT STATUS OF RISK MITIGATION 3-1 3.3 CARIFORUM AIRLINES 3-3 3.4 NON-CARIFORUM CTO MEMBERS 3-3 4. Optimising the Liberalisation Mechanism 4-1 4.1 THE LATIN AMERICAN/CARIBBEAN EXPERIENCE 4-2 4.2 INTERNATIONAL ‘OPEN SKIES’ 4-2 4.3 THE CARIFORUM STATUS 4-3 4.4 INTRA-REGIONAL ‘OPEN SKIES’ 4-4 5. Strengthening the Domicile Airlines 5-1 5.1 RECOMMENDATIONS 5-1 Appendices APPENDIX A: Preliminary Report - The Current Aviation Environment in the Caribbean A-1 APPENDIX B: Interim -

T-100 & T-IOO(F) INTERNATIONAL MARKET DATA DATA BANK 28IM

T-100 & T-IOO(f) INTERNATIONAL MARKET DATA DATA BANK 28IM 1992 DOCUMENTATION Record Group 398 Bureau of Transportation Statistics February 19, 1998 ' National Archives and Records Administration NARA Reference Copy NationalA h·. .-"7~"u~~"~coR,,,,,, .rirC ~VeS at College Park · \ 8601 Adelphi Road College Park, Maryland 20740-6001 · List of Documentation File Title: T-100 & T-1 OO(f) International Market Data, DB 28IM 1992 Accession Number: 3-398-96-009 Number ofPages I. NARA Documentation 1. NARA Produced Printout of Some Records· (2/19/98) 1 2. Sample Computer Printouts [1992] 1 4. User Note 1 1 II. Agency Documentation 1. Department of Transportation, Office of Airline Statistics 2 T-100 International Market Data Record Layout 2. T-100 International Market Record Description ofFields 1 3. OAS Data File Description 1 4. Additional information on Service Class codes from 2 the Code of Federal Regulations 5. U.S. Department of Transportation, Research and 12 Special Programs Administration. Wor~d Area Codes. 6. Carrier Codes Decode List 19 7. Office Airline Guide-Worldwide Edition. City Airport Codes 8 8. OAS Airport Codes Assigned Where No IATA Airport Code Exists. 6 ill. NARA Automated Validation Reports and Checklist 1. Auto.mated Validation ofElectronic Records 2: AERIC Record Layout Report 3. AERIC Domains Detail Report 4: AERIC Checklist for Validation 5. AERIC Load Report 6. AERIC Validation Statement: Summary Report .7. AERIC Dataset Contents Report IV. '· Supplementary Information , L:Office of Airline Information. Description ofthe T-100 Statistics Program 3 2. Office of Airline Information. Source of Air Carrier Aviation Data 9 3. -

The 8-December Murders in Surinam and United States Reactions During the Early 1980S

The 8-December Murders in Surinam and United States Reactions During the Early 1980s Date: 9 June 2006 Caroline Wentzel Student number: 9609059 MA Thesis English Language and Culture Specialisation: History of International Relations Supervisors: Dr. M. Kuitenbrouwer and Dr. P. Franssen To Lida, Herman and Emmanuel “Great is the art of beginning, but greater is the art of ending.” Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Table of contents Introduction----------------------------------------------------------------------------1 Chapter 1: Political and Social Developments after the Coup d'état of February 1980 § 1.1 The Revolution of the Sergeants: How "Old Politics" Became New Politics-----------------------------5 § 1.2.1 A Promising Start---------------------------------------------------6 § 1.2.2 Unity Becomes Diversity------------------------------------------8 § 1.2.3 The Left-Wing Fraction Loses the Lead------------------------ 10 § 1.2.4 Left-Wing Politics Regain Influence-----------------------------12 § 1.3 Protest Arises against Bouterse's Politics------------------------13 § 1.4 Conclusion-----------------------------------------------------------17 Chapter 2: The 8-December Murders: The Actual Events and the Direct Outcome § 1.1 The December Murders-------------------------------------------18 § 1.2.1 The Scenario and Its Contrivers---------------------------------18 § 1.2.2 The Victims-------------------------------------------------------- 21 § 1.2.3 The Execution of the Scenario-----------------------------------24 § 1.2.4 Determining