Summer/Fall 2020 Article 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interview with Jill Long Thompson, Ph.D

The Journal of Values-Based Leadership Volume 13 Issue 2 Summer/Fall 2020 Article 22 July 2020 Interview with Jill Long Thompson, Ph.D. Elizabeth Gingerich [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/jvbl Part of the Business Commons Recommended Citation Gingerich, Elizabeth (2020) "Interview with Jill Long Thompson, Ph.D.," The Journal of Values-Based Leadership: Vol. 13 : Iss. 2 , Article 22. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.22543/0733.132.1338 Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/jvbl/vol13/iss2/22 This Interview is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Business at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Journal of Values-Based Leadership by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Interview and Discussion JILL LONG THOMPSON June 9, 2020 Argos, Indiana, USA ― by Elizabeth F. R. Gingerich Q: Firstly, congratulations on your new book, The Character of American Democracy. Is this your first? This is my first book. I have done quite a bit of writing in my work in academia and public service, but this is my first and I think my last book. Q: Why your last? 1 It’s tiring. Q: When did you begin writing? As I recall, I started this in 2017 and I think I finished it in the late fall of 2018. Q: Actually, that didn’t take long! It seemed like it! Q: What was the precipitating factor that motivated you to write this book? Well, I have always felt that professional ethics are integrally tied to democracy and I also believe to a strong capitalist economy. -

Manchester Historical Society

The weather Inside today Clear and cool tonight with lows around 50 degrees. Wednesday mostly sunny with highs in the middle 70s. Area news............6 Family.......... ',2 Chance of rain near zero tonight and 10 Classified........9-10 Obituaries ... 1} per cent on Wednesday. Northwest Comics.............. 11 Sports...............7-D winds around 10 mph tonight. Manche$ter—-A City of Village Charm Northwest winds 10 to 15 mph on Wednesday. National weather forecast map on Page 9. TW tLVE PAGES MANCHESTER, CONN., TUESDAY, JULY J8,1977 - VOL, XCVI, No,' 251 I'RIGKi EIPI'EEN CKISTS Cluster zone denied By GREG PEARSON the northwest corner of Hillstown 136 single-family homes on the site, Residents of the area, which is Herald Reporter Rd. and Woodside St. The approval was supported by the residents. predominantly Residence AA Zone, The Manchester Planning and included conditions that the • Approved a seven-lot subdivision had voiced objections to both of these Zoning Commission (PZC) Monday developer install curbing and raise plan on Vernon St. that had been sub items when speaking against the night voted 3-2 to deny a Residence the level of the driveway. mitted by Joseph Swensson Jr. The proposal. They had said that the AA Cluster subdivision proposed for • Approved a Residence AA Zone commission also issued an inland- detention ponds would be a safety the Lenti Farms tract off Gardner St. for the 68.4-acre Walek tract off wetlands permit for the project, hazard for the neighborhood and that . The proposal, submitted by Keeney St. The zone change from which is near the Richmond Rd. -

PTW14-Program.Pdf

performing the world 2014 Participant Countries Argentina Denmark Nepal Romania Australia England Netherlands Scotland Austria Ghana Nicaragua Serbia Bangladesh Greece Nigeria South Africa Norway Botswana India Taiwan The Sultanate Brazil Israel of Oman Uganda Canada Italy Pakistan United States Chile Japan Peru Colombia Mexico Philippines (as of 10/21/14) how shall we become? NEW YORK CITY performing the world 2014 Contents Greetings ...............................................................page 3 Schedule ................................................................page 11 Session Descriptions ...........................................page 19 Visitors Guide .......................................................page 51 Thanks ....................................................................page 59 Welcome from the All Stars Project On behalf of the All Stars Project’s board of directors, staff, donors, young people Note: You will find presenter bios online at www.performingtheworld.org and volunteers, I welcome you to Performing the World 2014 and to the All Stars Project’s performing arts and development center. We are proud to be co- sponsoring this extraordinary international gathering. “How Shall We Become?” is a question that permeates everything we do at the All Stars. How shall the people we work with —young people and adults, from corporate boardrooms to inner-city communities — become deeper, broader, more worldly and more developed? We can never know in advance what we shall become, but we believe that how we become — through play and performance — gives us all the best chance for development. performing We look forward to these three days of asking “How Shall We Become?” with all of you. We hope you enjoy our theatres, our volunteer staff, New York City — and “becoming” together. the Warm regards, world 2014 Gabrielle L. Kurlander President and CEO All Stars Project, Inc. -

Politics Indiana

Politics Indiana V14 N44 Tuesday, June 24, 2008 JLT labors under the unity facade UAW, Schellinger don’t join Jill’s Convention confab By RYAN NEES INDIANAPOLIS - Jill Long Thompson has work still to do with the party faithful, who at the state convention Saturday appeared more swept by the candidacy of Barack Obama and even the muted appearances by the Hoosier Congressional delegation than of Indiana’s first female gubernato- rial nominee. And behind the scenes, the machinery of the Democratic establishment still appears to be exacting upon her nothing short of malicious ven- geance. The candidate was met with polite ap- plause as she toured district and interest group caucus meetings, but skepticism persisted especially amongst the roughly half of the party that supported her opponent in Indiana’s May primary. That unease was punctuated dramatically by the UAW’s refusal to endorse her candidacy the morning of the conven- tion, a move that appeared designed to rain on the nominee’s parade. Jill Long Thompson listens to her brother talk about her life and candidacy The UAW’s support provided vital to archi- just prior to taking the stage Saturday at the Indiana Democratic Conven- tect Jim Schellinger’s primary tion. (HPI Photo by Brian A. Howey) campaign, which received See Page 4 Back home again with Jill By BRIAN A. HOWEY NASHVILLE, Ind. - In the Hoosier brand of guber- natorial politics, home is where the heart is. We remember Frank O’Bannon talking about his “wired” barn down near Corydon. In January 2005, Mitch Daniels talked about an “These days many politicians Amish-style barn raising. -

New York Citytm

The Internationalist ® The Top 10 Guide to New York The Top 10 Guide to New York CityTM The Internationalist 96 Walter Street/Suite 200 Boston, MA 02131 USA The Internationalist • www.internationalist.com • 617-354-7755 1 The Internationalist ® The Top 10 Guide to New York The Internationalist® International Business, Investment and Travel Published by: The Internationalist Publishing Company 96 Walter Street/Suite 200 Boston, MA 02131, USA Tel: 617-354-7722 [email protected] Author: Patrick W. Nee Copyright © 2001 by PWN The Internationalist is a Registered Trademark. The Top 10 Guide to New York City, The Top 10 Travel Guides, The Top 10 Guides are Trademarks of the Internationalist Publishing Company. All right are reserved under International, Pan-American and Pan-Asian Conventions. No part of this book, no lists, no maps or illustration may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of the publisher. All rights vigorously enforced. ISBN: 1-891382-21-7 Special Sales: Books of the Internationalist Publishing Company are available for bulk purchases at special discounts for sales promotions, corporate identity programs or premiums. The Internationalist Publishing Company publishes books on international business, investment and travel. For further information contact the Special Sales department at: Special Sales, The Internationalist, 96 Walter Street/Suite 200, Boston, MA 02131. The Internationalist Publishing Company 96 Walter Street/Suite 200 Boston, MA 02131 USA Tel: 617-354-7722 [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] web site: http://www.internationalist.com The Internationalist • www.internationalist.com • 617-354-7755 2 The Internationalist ® The Top 10 Guide to New York Welcome to New York City. -

The Marriage Debate Heads for GOP Platform Fight, Treasurers Race to Headline Convention by BRIAN A

V19, N36 Tuesday, June 3, 2014 The marriage debate heads for GOP Platform fight, treasurers race to headline convention By BRIAN A. HOWEY NASHVILLE, Ind. – Sometime be- tween 10 a.m. and 2 p.m. this Saturday in Fort Wayne, the Indiana Republicans will chart a course that could impact their position as Indi- ana’s super majority party. The supposed 1,775 delegates (not all will show up) will make a determination on whether the party’s 2014 platform addresses the constitutional marriage amendment, and it will choose a state treasurer nominee who could expose the various fissures – Tea Party, establishment, money wings – of the party. Terre Haute attorney Jim Bopp Jr., who lost his Republican National Committee seat While the treasurer floor fight among in 2012 after proposing a party litmus test, is pushing the marriage platform plank. Marion Mayor Wayne Seybold, Don Bates Jr., and Kelly Mitchell has been the long-anticipated nor Democrats took a platform stance on the marriage is- event for the Indiana Republican Convention, it is the plat- sue. form, normally an obscure, rote exercise that rarely influ- The Republican platform committee did not take ences voters, that could define Hoosier Republicans for the next several years. In 2012, neither Indiana Republicans Continued on page 3 A doozy of a convention By CRAIG DUNN KOKOMO – The Indiana Republican State Conven- tion, June 6-7 in Fort Wayne, is shaping up to be quite an event, promising to change this sleepy little election year into a good old-fashioned Hoosier barnburner. In a phenomenon that “It seems the governor has been happens every 12 years, the election ticket will be headed by everywhere of late but Indiana.” the secretary of state race this - John Gregg, speaking year. -

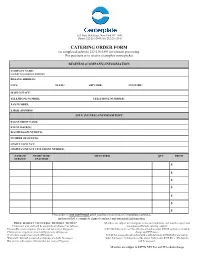

Catering Order Form

%$$Xr"#uT rrIr` xI` Qur)! !! %!#Ah)! !! %!#($ Ahpyrrq qr ! !! %!#($s p hp prvt A rv rprvrhpyrrrhpxr vpyqriuhrvsqvssr r Uuv qr v !" #! $%&'() vyuhr rprvrqh8rr yhrp hp hq vqrqhpyrrvtrqp hphqhrvs hv * + 6yy qr h riwrp8rr yhrr hqpqvvhqirvtrqhq Vvs rqhvhssvyyirhvtrqhqpuhtrqhsyy) hpphvrqi phr vt rr 9vhiyrr vpr rv r hvhssr rr #tr 68"$qryvr srrvyyirhqqrqhyy qr qr 8$rpyvrshqv 8uvhr vpr rv r hvhssr rr !tr puh trhqI`Thr 8hhv rv rqr rr !tr 8"$srrhrrqhyy qr vuhihyqr 8"$uhh rrv Xhvhssih rqr rv rqqvrrhypuyvpirr htr qr s rr #qh v urrrP qr r 8"$0h ;yhrsrr 7h r vprvyy rv r ih rqr r rr &$tr vyyirhrrq ,, !&)(&- .&( -/01(#" "! 232456 .7 . ) 886 .)'% #9.&:( > CATERING MENU INDEX INDEX 2 INDEX Welcome to New York City! Welcome to New York City, a world-renowned Whatever your needs, whether hosting attendee receptions, destination for sophistication and style – supplying convenient meals for your booth staff, or creating custom menus for unique occasions, we are dedicated to where the natural beauty of ocean and helping you achieve extraordinary results. Please give us a shore is matched only by the warmth and call to start the planning process today! energy of an exciting community. Here’s to your successful event in New York, Centerplate is a leading global event hospitality company, and we are thrilled to be your exclusive hospitality partner at the Javits Center. Our style is collaborative, and our New York Anna Ference team is delighted to work with you to ensure your experience here in this New York is smooth, successful, and enjoyable. Anna Ference We are committed to delivering the finest food, amenities, Director of Catering Sales, Centerplate and service to impress your guests. -

The Howey Political Report Is Published by Newslink Tive Congressional Races on Our Landscape: 2Nd CD Between Inc

Monday, July 1, 2002 ! Volume 8, Number 39 Page 1 of 8 Setting the stage for The Indiana’s CD races Howey !"##$%&'()&*(+,%&'-./,&%0-1%.#%)&2%)%& By BRIAN A. HOWEY in Indianapolis Tax restructuring and deficit reduction and cigarettes and dockside and the old Dog Doctor and Speaker Bauer and Political blah, blah, blah, and ... ... now for something completely different. Like that other huge Hoosier political story of 2002: Report Our role as epicenter for control of the U.S. House of Representatives. HPR sees three, and possibly four, competi- The Howey Political Report is published by NewsLink tive Congressional races on our landscape: 2nd CD between Inc. Founded in 1994, The Howey Political Report is Democrat Jill Long Thompson and Republican Chris an independent, non-partisan newsletter analyzing the Chocola; 6th CD between U.S. Rep. Mike Pence and political process in Indiana. Democrat Melina Ann Fox; 7th CD where Republican Brose Brian A. Howey, publisher McVey is showing a tenacious streak against U.S. Rep. Julia Mark Schoeff Jr., Washington writer Carson; and the 9th CD where Republican Mike Sodrel is Jack E. Howey, editor expected to press U.S. Rep. Baron Hill. HPR views the Thompson-Chocola race as a pure The Howey Political Report Office: 317-968-0486 tossup. Currently, Reps. Hill and Carson are in the “Leans PO Box 40265 Fax: 317-968-0487 Indianapolis, IN 46240-0265 Mobile: 317-506-0883 D” range and Pence is in a “Leans R” status and of the lot, Pence may be in the best position of incumbents ... for now. -

Politics Indiana

Politics Indiana V14 N40 Thursday, May 22, 2008 Daniels, Kernan reforms attacked Sen. Waterman independent \Gov. Mitch Daniels visited bid, attorney general race Hoosier troops in the Iraq war could change ‘08 dynamic zone earlier this week, but he By BRIAN A. HOWEY faced an insur- INDIANAPOLIS - The 2008 Indiana rection led by gubernatorial race is on the brink of a signifi- State Sen. John cant dynamic change with the pending entry Waterman (be- of State Sen. John Waterman as an indepen- low) at home. dent candidate, in part fueled by anger over the Kernan-Shepard reforms. In tandem with thing will shake former LaPorte County Democratic chairman out. I don’t know how wide that appeal Shaw Friedman’s “open letter” to former Gov. will be.” Joe Kernan (see below), the reforms are under Waterman said he needs 33,000 assault from wings of both parties. The three- signatures to qualify. But unlike a primary term Republican senator continues to signal candidacy, they don’t have to come equal- to friends and colleagues that he is preparing ly from the nine congressional districts. entry. The critical question is whether he can “They could all come from Indianapolis or obtain the 33,000 signatures to qualify for the down here,” Waterman said. Asked if he ballot by June 30. thought he could gather the signatures Cam Savage, communication director in six weeks, Waterman answered, “Yes. for Gov. Mitch Daniels’ re-election campaign, We’ve got people working statewide.” He was asked if he felt Waterman could get on said there are “statewide organizations” the ballot. -

New Fall Theatre Rocking Concerts Little Italy Dining

OCT 2014 OCT ® MUSEUMS | City's best meals from the boot the from meals best City's Little Italy Dining Italy Little New Fall Theatre Fall New Star talent on Broadway this talentStar on Broadway month Rocking Concerts Music's descend upon stars biggest NYC BROADWAY | DINING | ULTIMATE MAGAZINE FOR NEW YORK CITY FOR NEW YORK MAGAZINE ULTIMATE SHOPPING NYC Monthly OCT2014 NYCMONTHLY.COM VOL. 4 NO.10 B:13.125 in T:12.875 in S:12.75 in S:8.9375 in B:9.3125 in T:9.0625 in T:9.0625 43418RL_AD20116_5thAve_NYMonthly-Sprd.indd All Pages 8/14/14 3:56 PM Date:August 13, 2014 6:11 PMProofreader Page: 1 Project Mgr Studio Ad Design MISC. PRINT SPECS Artist: Angela Graphic Service Stock: SWOP Round FTP Brand Mgr Quantity: N/A Inks: CMYK + 4C Match PMS 295C Notes/Misc: LOGO IS PMS 295C FROM 4C TINTS Approved to Release ESCADA.COM 0230_US_ESC_Img3_NYC_monthly_09_2014.indd Alle Seiten 13.08.14 17:28 1OOO EXCLUSIVES • 1OO DESIGNERS • 1 STORE Contents Cover Photo: George Washington Bridge at dawn © Jason Pierce. Opened in 1931 and standing high above the Hudson River, the GW Bridge is a double-decker suspension bridge that connects the Washington Heights neighborhood of Manhattan to Fort Lee, New Jersey. A marvel of engineering, it is also the world’s busiest motor vehicle bridge, accommodating nearly 50 million New York-bound vehicles in 2013 alone. When completed in 1931, it was the longest suspension bridge in the world, utilizing 107,000 miles of wire in its cables. -

Interview with Jill Long Thompson) Elizabeth Gingerich Valparaiso University, [email protected]

The Journal of Values-Based Leadership Volume 3 Article 2 Issue 1 Winter/Spring 2010 January 2010 Introducing Ethics Legislation: The ourC age to Lead After 200 Years of Silence (Interview with Jill Long Thompson) Elizabeth Gingerich Valparaiso University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/jvbl Part of the Business Commons Recommended Citation Gingerich, Elizabeth (2010) "Introducing Ethics Legislation: The ourC age to Lead After 200 Years of Silence (Interview with Jill Long Thompson)," The Journal of Values-Based Leadership: Vol. 3 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/jvbl/vol3/iss1/2 This Interview is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Business at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The ourJ nal of Values-Based Leadership by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. My moral principles tell me that if I’m an elected official, my vote should be consistent with what my constituents would want if they had the same information that I have; if they had the opportunity to sit in the briefings and in the hearings. I never really found morality – my morality – to be that different from the broader range of my constituents that I represent. What I thought was important was doing what I believed was consistent with their values, but taking into account the more detailed information that I had. — The Honorable Jill Long Thompson, 2009 Introducing Ethics Legislation: The Courage to Lead After 200 Years of Silence __________________________________________________________________________ THE HONORABLE JILL LONG THOMPSON U.S. -

View Booklet

V SCHEDULE YOUTH BUSINESS SUMMIT / 2019 Table of Contents MONDAY/APRIL 15, 2019 3 … Schedule 18 … National Competitions: National Business Plan Competition Hosted by Microsoft Technology Center Finance 9:00 AM - 2:00 PM Preliminary Round 4 … Letter from HSBC Human Resources 2:30 PM - 6:30 PM Championship Round Marketing Announcement of winners at the conclusion of the Championship Round 5 … Letter from the President & VE Board of Directors Chair 26 … Global Business Challenge National Competitions (Finance, HR, Marketing) at Microsoft Technology Center … International Trade Exhibition 6 … About VE 30 10:30 AM - 2:00 PM Presentations 2:30 PM - 6:30 PM Championship Round 7 … Event Descriptions 38 … Board & Staff Announcement of winners on Wednesday during the International Trade Exhibition Opening Ceremony 8 … Partners & Sponsors Gala Booklet (flip booklet over) 9 … Speakers TUESDAY/APRIL 16, 2019 Global Business Challenge Powered by Intuit at LIU Brooklyn 12 … National Business Plan Competition 7:30 AM - 1:00 PM Preliminary Round 1:00 PM - 3:00 PM Championship Round International Trade Exhibition Kickoff at Brooklyn Cruise Terminal Share your Youth Business Summit journey 2:00 PM - 4:00 PM Early Registration and Set-Up for Exhibitors with #2019YBS on Instagram and Twitter. 4:00 PM - 7:00 PM #2019YBS Kickoff Party with special musical guest Phony Ppl and Live International Fashion Show Hosted by FLY NY from The High School of Fashion Industries Find more information at veinternational.org/2019-ybs WEDNESDAY/APRIL 17, 2019 International Trade