A Study in Form: Recognition Scenes in the Three Electra Plays*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 IPHIGENIA in TAURIS by Euripides Adapted, Edited, and Rendered Into

IPHIGENIA IN TAURIS by Euripides Adapted, edited, and rendered into modern English for the express purpose of dramatic performance by Louis Markos, Professor in English and Honors Scholar-in-Residence/Robert H. Ray Chair in Humanities Houston Baptist University (Houston, TX) Dramatis Personae IPHIGENIA, daughter of Agamemnon ORESTES, brother of Iphigenia PYLADES, friend of Orestes THOAS, King of the Taurians HERDSMAN MESSENGER ATHENA CHORUS of captive Greek women who serve Iphigenia SCENE Before the temple of Artemis in Tauris. (Iphigenia, dressed as a priestess, enters and stands before the altar.) IPHIGENIA From Asia Pelops came to the shores of Greece; His son was Atreus and from him came Two greater sons, skilled in the arts of war. The eldest, Agamemnon, rules Mycenae While Menelaus holds the throne of Sparta. For Helen’s sake they raised a mighty fleet And set their sails for Troy. But Artemis, Beloved sister of the god Apollo, Sent vexing winds to wrestle with their sails And strand them on the rocky shore of Aulis. Eager to conquer Troy and so avenge His brother’s bed, my father, Agamemnon, Ordered Calchas, prophet of the host, To seek the will of Zeus and to proclaim The cause of their misfortune–and the cure. “O King,” he spoke, “You must fulfill the vow You made to Artemis: to offer up The dearest treasure that the year would bring. 1 The daughter born to you and Clytemnestra— She is the treasure you must sacrifice.” I was and am that daughter—oh the pain, That I should give my life to still the winds! The treacherous Odysseus devised The plot that brought me, innocent, to Aulis. -

Iphigenia in Aulis by Euripides Translated by Nicholas Rudall Directed by Charles Newell

STUDY GUIDE Photo of Mark L. Montgomery, Stephanie Andrea Barron, and Sandra Marquez by joe mazza/brave lux, inc Sponsored by Iphigenia in Aulis by Euripides Translated by Nicholas Rudall Directed by Charles Newell SETTING The action takes place in east-central Greece at the port of Aulis, on the Euripus Strait. The time is approximately 1200 BCE. CHARACTERS Agamemnon father of Iphigenia, husband of Clytemnestra and King of Mycenae Menelaus brother of Agamemnon Clytemnestra mother of Iphigenia, wife of Agamemnon Iphigenia daughter of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra Achilles son of Peleus Chorus women of Chalcis who came to Aulis to see the Greek army Old Man servant of Agamemnon, was given as part of Clytemnestra’s dowry Messenger ABOUT THE PLAY Iphigenia in Aulis is the last existing work of the playwright Euripides. Written between 408 and 406 BCE, the year of Euripides’ death, the play was first produced the following year in a trilogy with The Bacchaeand Alcmaeon in Corinth by his son, Euripides the Younger, and won the first place at the Athenian City Dionysia festival. Agamemnon Costume rendering by Jacqueline Firkins. 2 SYNOPSIS At the start of the play, Agamemnon reveals to the Old Man that his army and warships are stranded in Aulis due to a lack of sailing winds. The winds have died because Agamemnon is being punished by the goddess Artemis, whom he offended. The only way to remedy this situation is for Agamemnon to sacrifice his daughter, Iphigenia, to the goddess Artemis. Agamemnon then admits that he has sent for Iphigenia to be brought to Aulis but he has changed his mind. -

The Iphigenia in Tauris of Euripides; Online

cWtqn (Download) The Iphigenia in Tauris of Euripides; Online [cWtqn.ebook] The Iphigenia in Tauris of Euripides; Pdf Free Euripides, Murray Gilbert 1866-1957 ebooks | Download PDF | *ePub | DOC | audiobook 2016-05-04Original language:English 9.21 x .31 x 6.14l, .78 #File Name: 1355439914 | File size: 53.Mb Euripides, Murray Gilbert 1866-1957 : The Iphigenia in Tauris of Euripides; before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Iphigenia in Tauris of Euripides;: 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Euripides solves the mystery of Iphigenia after AuliusBy Lawrance BernaboAt the end of "Iphigenia at Aulius," when the virgin daughter of Agamemnon is about to sacrificed offstage to appease the goddess Artemis, as the fatal blow is struck the young girl disappears and a stage appears in its place. Thus, at the last minute, Euripides refrains from suggesting a goddess demanded a human sacrifice. But what happened to the young girl? The dramatist provides his answer in "Iphigenia in Tauris" Artemis saved Iphigenia and brought her to the temple of the goddess in Tauris (which is in Thrace, although others take this to mean the Crimea). Meanwhile, her brother Orestes, still trying to appease the Furies for his crime of matricide, is ordered by the god Apollo to bring the statue of Artemis from Tauris to Athens. However, the Taurians have the quaint habit of sacrificing strangers to the goddess (so much for the goddess disdaining human sacrifice). Once again, Euripides is showing his disdain for Apollo; at first consideration you might think Apollo is setting up the reconciliation of brother and sister, but since it is up to the goddess Athena to help the pair, and Orestes's friend Pylades, to escape, the clearly implication is that Apollo wants Orestes dead."Iphigenia in Taurus" ("Iphigeneia en Taurois," which is also translated as "Iphigenia among the Taurians") is really more of a tragicomedy than a traditional Greek tragedy. -

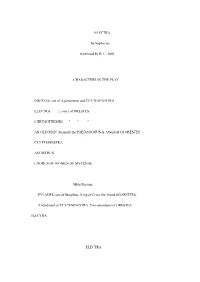

ELECTRA by Sophocles Translated by R. C. Jebb CHARACTERS in THE

ELECTRA by Sophocles translated by R. C. Jebb CHARACTERS IN THE PLAY ORESTES, son of Agamemnon and CLYTEMNESTRA ELECTRA } sister of ORESTES CHRYSOTHEMIS} " " " AN OLD MAN, formerly the PAEDAGOGUS or Attendant Of ORESTES CLYTEMNESTRA AEGISTHUS CHORUS OF WOMEN OF MYCENAE Mute Persons PYLADES, son of Strophius, King of Crisa, the friend Of ORESTES. A handmaid of CLYTEMNESTRA. Two attendants of ORESTES ELECTRA ELECTRA (SCENE:- At Mycenae, before the palace of the Pelopidae. It is morning and the new-risen sun is bright. The PAEDAGOGUS enters on the left of the spectators, accompanied by the two youths, ORESTES and PYLADES.) PAEDAGOGUS SON of him who led our hosts at Troy of old, son of Agamemnon!- now thou mayest behold with thine eyes all that thy soul hath desired so long. There is the ancient Argos of thy yearning,- that hallowed scene whence the gadfly drove the daughter of Inachus; and there, Orestes, is the Lycean Agora, named from the wolf-slaying god; there, on the left, Hera's famous temple; and in this place to which we have come, deem that thou seest Mycenae rich in gold, with the house of the Pelopidae there, so often stained with bloodshed; whence I carried thee of yore, from the slaying of thy father, as thy kinswoman, thy sister, charged me; and saved thee, and reared thee up to manhood, to be the avenger of thy murdered sire. Now, therefore, Orestes, and thou, best of friends, Pylades, our plans must be laid quickly; for lo, already the sun's bright ray is waking the songs of the birds into clearness, and the dark night of stars is spent. -

Late Sophocles: the Hero's Evolution in Electra, Philoctetes, and Oedipus

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE Late Sophocles Late Sophocles The Hero’s Evolution in Electra, Philoctetes, and Oedipus at Colonus Thomas Van Nortwick University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Copyright © Thomas Van Nortwick 2015 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and ex- cept by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by the University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2018 2017 2016 2015 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Van Nortwick, Thomas, 1946– . Late Sophocles : the hero’s evolution in Electra, Philoctetes, and Oedipus at Colonus / Thomas Van Nortwick. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 472- 11956- 1 (hardcover : alk. paper) — ISBN 978- 0- 472- 12108- 3 (ebook) 1. Sophocles— Criticism and interpretation. 2. Sophocles. Electra. 3. Sophocles. Oedipus at Colonus. 4. Sophocles. Philoctetes. I. Title. PA4417.V36 2015 882'.01— dc23 2014049364 For Nathan Greenberg colleague, mentor, and friend Preface Oh children, follow me. I am your new leader, as once you were for me. (Sophocles, Oedipus at Colonus 1542– 431) Sophocles’s Oedipus at Colonus ends with his most famous character walking serenely through the central doors of the stage building (skēnē) in the Theater of Dionysus and into the grove of the Eumenides. -

Greek Tragedy in Modern Greece

ALL IS WELL THAT ENDS TRAGICALLY: FILMING GREEK TRAGEDY IN MODERN GREECE ANASTASIA BAKOGIANNI The king’s a beggar now the play is done: All is well ended, if this suit be won, That you express content; which we will pay With strife to please you, day exceeding day. Ours be your patience, then, and yours our parts: Your gentle hands lend us, and take our hearts. William Shakespeare, All’s Well that Ends Well What does it take to adapt Greek tragedy successfully for the cinema?’ The debate centres on the issue of authenticity2 as well as the question of the successful integration of tragedy into the cinematic medium. The problematic nature of any attempt to adapt Greek tragedy for the cinema makes it a particularly challenging enterprise for filmmakers.3 In comparison with the cinematic reception of other aspects of ancient Greece and Rome, attempts to film Greek tragedy offer us fewer examples to work but they do attract the talents of some of the world’s best independent film directors,5 who have created some remarkable cincmatic receptions. ’ This is an exciting and ongoing debate and one articlc cannot hope to encompass all the issues concerned. The present article will focus on one aspect of this debate and is indebted to the pioneering work of Professor Marianne McDonnald and Dr Pantelis Michelakis in the field of the reception of Greek Drama on film. The author is also greatly indebted to Professor Mike Edwards and Professor Charles Chiasson for their many helpful suggestions. I am also indebted to Mr. -

Liz White Is an Actor Who Has Appeared in a Wide Variety of Roles on Stage and in Film and Television

Liz White is an actor who has appeared in a wide variety of roles on stage and in film and television. One of her most recent film roles was in Pride (2014) directed by Marcus Warchus. Among her other film roles, Liz has played Pamela in Vera Drake (2004) directed by Mike Leigh, and she starred as the eponymous woman in the 2012 film version of The Woman in Black, based on the novel by Susan Hill. For BBC Television, Liz played WPC/WDC Annie Cartwright in Life on Mars (2006/7), Caroline in the adaptation of The Crimson Petal and the White (2011), and Lizzie Mottershead in the series Our Zoo (2014). Other television roles have been Eileen in Teachers (2003), Jess Mercer in The Fixer (2008), and Lucille in The Paradise (2013). Liz’s stage credits have included three acclaimed performances at the National Theatre. She played Heavenly Critchfield in Laurie Sansom’s production of Spring Storm by Tennessee Williams, which transferred from the Royal and Derngate, Northampton, to the Cottesloe (2010), Anne Frankford in A Woman Killed With Kindness by Thomas Heywood, directed by Katie Mitchell in the Lyttelton (2010), and double roles in Marianne Elliot’s revival of Port by Simon Stephens in the Lyttelton (2013). In Autumn, 2014, Liz played the role of Chrysothemis in Ian Rickson’s production of Sophocles’ Electra at the Old Vic Theatre. The production used the version of the play written by Frank McGuinness and starred Kristin Scott Thomas as Electra. In this interview, recorded by Chrissy Combes at the Old Vic Theatre on Thursday 11 December 2014, Liz talked about the experience of playing Chrysothemis, Electra’s sister. -

Sophocles' Electra

Sophocles’ Electra Dramatic action and important elements in the play, scene-by-scene Setting: Mycenae/Argos Background: 15-20 years ago, Agamemnon (here named as grandson of Pelops) was killed by his wife and lover Aegisthus (also grandson of Pelops). As a boy, Orestes, was evacuated by his sister Electra and the ‘Old Slave’ to Phocis, to the kingdom of Strophius (Agamemnon’s guest-friend and father of Pylades). Electra stayed in Mycenae, preserving her father’s memory and harbouring extreme hatred for her mother Clytemnestra and her lover Aegisthus. She has a sister, Chrysothemis, who says that she accepts the situation. Prologue: 1- 85 (pp. 169-75) - Dawn at the palace of Atreus. Orestes, Pylades and the Old Slave arrive. Topography of wealthy Argos/Mycenae, and the bloody house of the Atreids. - The story of Orestes’ evacuation. ‘It is time to act!’ v. 22 - Apollo’s oracle at Delphi: Agamemnon was killed by deception; use deception (doloisi – cunning at p. 171 is a bit weak) to kill the murderers. - Orestes’ idea to send the Old Slave to the palace. Orestes and Pylades will arrive later with the urn containing the ‘ashes’ of Orestes. «Yes, often in the past I have known clever men dead in fiction but not dead; and then when they return home the honour they receive is all the greater» v. 62-4, p. 173 Orestes like Odysseus: return to house and riches - Electra is heard wailing. Old slave: “No time to lose”. Prologue: 86-120 (pp. 175-7) - Enter Electra, who addresses the light of day. -

Elektra 2017

B Y J ANE G ANAHL The Many Faces of S E G A M I N A M E G Elektra D I R B ou may have seen her in the form of Jennifer YGarner’s sword-wielding assassin in the 2005 film Elektra , on stage as a bitter Civil War spin - ster in Eugene o’Neill’s Mourning Becomes Electra , in the words of Sylvia Plath’s controversial poem “Electra on Azalea Path,” in the famed portrait by Frederic Leighton, Electra at the Tomb of Agamemnon , and indeed, in Richard Strauss’ opera Elektra* . K U , In the 2,000-plus years since her name was first S M U etched on paper, Electra—the myth, the character—has E S U inspired dozens, if not hundreds, of works of theater, lit - M L L erature, art, opera, and psychoanalysis. Around a cen - U H , tury ago, Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung suggested there y R E L was an “Electra complex” suffered by many little girls L A G who were in love with their fathers in competition with T R A their mothers, thus tainting forever the innocent tag S N E “Daddy’s little girl.” R E F Even today, the vengeful, father-worshipping anti-heroine / S E of Sophocles’ tragedy continues to fascinate and perturb G A M I us—perhaps in part because her story of familial murder N A and mayhem makes Game of Thrones pale in comparison. M E G In the years following the Trojan War, Electra has waited D I R B for nearly a decade for the return of her brother orestes *When referring to the Sophocles play, the standard English spelling is “Electra.” “Elektra” is the German spelling. -

Iphigenia in Tauris.Intro

IPHIGENIA IN TAURIS In this introduction, I will 1) give an overview of the plot, 2) consider some of the unique features of the play, and 3) discuss the process I went through in adapting the play. Euripides’ Iphigenia offers a different take on the fall of the house of Atreus. Here is the story in its classic form as told in Aeschylus’ Oresteia. 1) The sons of Atreus, Agamemnon and Menelaus, become kings of Mycenae and Sparta and take as wives the sisters Clytemnestra and Helen. 2) Paris’s abducts Helen, igniting the Trojan War; the Greeks navy is led by Agamemnon. 3) Before they can sail for Troy, the fleet is grounded at the Port of Aulis, and Agamemnon is told that the goddess Artemis will not let him sail unless he sacrifices his daughter, Iphigenia. 4) Agamemnon instructs Iphigenia to come to Aulis where she will be married to Achilles, but when she arrives, he sacrifices her. 5) While the Greeks fight at Troy for ten years, Clytemnestra, enraged at Agamemnon’s murder of their daughter, takes a lover. 6) When Agamemnon returns from Troy, his wife kills him. 7) Many years later, Agamemnon’s son, Orestes returns home and, with the help of his sister, Electra (and the guidance of Apollo), kills his mother and her lover. 8) Because he is guilty of matricide, Orestes is chased by the Furies, but Apollo and Athena intercede for him, and he is declared innocent at a trial held in Athens. To this tragic plot, Euripides makes two important changes. -

An Examination of the Gender Roles of Clytemnestra and Electra

Rebellious Performances: An Examination of the Gender Roles of Clytemnestra and Electra Bethany Nickerson Honors Thesis-English Department Advisor: Jeffrey DeShell, English Cathy Preston, English John Gibert, Classics March 22, 2012 Nickerson 1 Abstract This thesis seeks to create an understanding of the mythological characters of Clytemnestra and Electra as they were portrayed by Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. By examining these plays in conjunction with the historical setting in which they were written and performed, this discussion shows how these two female characters play masculine roles in order to achieve their desires. These fictional women reveal how the real-life women of Classical Athens, were always caught in a double bind due to the patriarchal society in which they lived. This thesis examines the plays of these playwrights in their original Greek in order to examine how these women play masculine roles though their actions as well as the very words they use. This discussion ends with an examination of these female characters in relation to the male character Orestes which shows how these women are ultimately unsuccessful in their attempts to achieve their desires because they are, in the end, women. Nickerson 2 From the haunting song of the seductive sirens to the killing glare of Medusa and from the terrifying features of the chimera to the deadly riddles of the Sphinx, the feminine often appears in Greek mythology as perilous and evil. In the literature and myths of the Greeks from the earliest poems of the archaic period to the sophisticated dramas of Classical Athens, there emerges a pervasive fear of women. -

Podcast Episode 8 Draft Transcript.Pages

!1 Staging the Archive: APGRD Podcast: Episode 8: Transcript University Classical Plays a podcast with guest presenter David Bullen interviewing: Lewis Bentley, Elena Bashkova, Zoë De Barros, Marcus Bell, and Alison Middleton introduced by Giovanna Di Martino Recorded December 2020 Giovanna Di Martino Hello, everybody. Welcome back to this holiday special. Today we are focusing on the university classical play tradition. So we have here with us the creative teams of both UCL and Oxford. I'm very pleased that to lead the conversation will be David Bullen. So David is a writer, director and dramaturg and he's currently a teaching fellow in the department of Drama, Theatre and Dance at Royal Holloway. In 2011, he co founded By Jove Theatre Company, a socialist feminist collective, that retells old stories new ways for contemporary Britain. His adaptations of Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, and Aristophanes have been performed in the UK and in the US. He is currently working on a book on Greek tragedy in 21st century British theatre for Liverpool University Press and he's a visiting research associate at King's. So David, over to you. David Bullen Thanks, Giovanna. Thanks so much. I'm really I'm delighted to be here. This is great. This is fun, what a festive treat to be here after this crazy pandemic inflicted term, It's so lovely to hear to be talking about theatre of all things, one of the things we've really lost in the last couple of months. But actually, that loss is sort of our subject today, because some the things we may have lost but other things we have gained.