Solidarity: Reflections on an Emerging Concept in Bioethics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stop Solidarity's Counterrevolution!

Time Runs Out in Poland Stop Solidarity's Counterrevolution! The massive strike in the Baltic ports last August brought Polish workers before a historic choice: with the bankruptcy of Stalinist rule dramatically demon strated, it would be either the path of bloody counter revolution in league with imperialism, or the path of proletarian political revolution. The Gdansk accords and the emergence of Solidarity (Solidarnosc), the mass workers organization which issued out of last year's general strike, produced a situation of cold dual power. This precarious condition could not last long, we wrote. And now time has run out. With its first national congress in early September, decisive elements of Solidarity are now pushing a program of open counterrevolution. The appeal for "free trade unions" within the Soviet bloc, long a fighting slogan for Cold War anti-Communism, was a deliberate provocation of Moscow. Behind the call for "free elections" to the Sejm (parliament) stands the program of "Western-style democracy, " that is, capitalist restoration under the guise of parliamen tary government. And now leading Polish "dissident" Jacek Kuron, an influential adviser of Solidarity, and a member of the Second International, has issued a call for a counterrevolutionary regime to take power. To underscore their ties to the "free world," Solidarity's leaders have invited Lane Kirkland, the hard-line Cold Warrior who heads up the American AFL-CIO, to attend the second session of the congress scheduled for late September. This top labor lieuten ant of U. S. imperialism, a man deeply involved in Washington's anti-Soviet war drive, has announced he . -

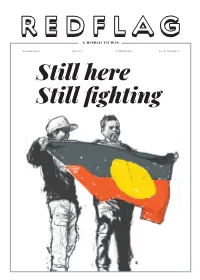

RF177.Pdf (Redflag.Org.Au)

A WORLD TO WIN REDFLAG.ORG.AU ISSUE #177 19 JANUARY 2021 $3 / $5 (SOLIDARITY) Still here Still fi ghting REDFLAG | 19 JANUARY 2021 PUBLICATION OF SOCIALIST ALTERNATIVE REDFLAG.ORG.AU 2 Red Flag Issue # 177 19 January 2021 ISSN: 2202-2228 Published by Red Flag Support the Press Inc. Trades Hall 54 Victoria St Carlton South Vic 3053 [email protected] Christmas Island (03) 9650 3541 Editorial committee Ben Hillier Louise O’Shea Daniel Taylor Corey Oakley rioters James Plested Simone White fail nonetheless. Some are forced to complete rehabil- Visual editor itation programs and told that when they do so their James Plested appeals will be strengthened. They do it. They fail. These are men with families in Australia. They Production are workers who were raising children. They are men Tess Lee Ack n the first week of 2021, detainees at the Christ- who were sending money to impoverished family Allen Myers mas Island Immigration Detention Centre be- members in other countries. Now, with their visas can- Oscar Sterner gan setting it alight. A peaceful protest, which celled, they have no incomes at all. This has rendered Subscriptions started on the afternoon of 5 January, had by partners and children homeless. and publicity evening escalated into a riot over the treatment Before their transportation from immigration fa- Jess Lenehan Iof hundreds of men there by Home Affairs Minister cilities and prisons on the Australian mainland, some Peter Dutton and his Australian Border Force. Four of these men could receive visits from loved ones. Now What is days later, facing down reinforced numbers of masked, they can barely, if at all, get internet access to speak to armed Serco security thugs and Australian Federal them. -

Commonwealth Responsibility and Cold War Solidarity Australia in Asia, 1944–74

COMMONWEALTH RESPONSIBILITY AND COLD WAR SOLIDARITY AUSTRALIA IN ASIA, 1944–74 COMMONWEALTH RESPONSIBILITY AND COLD WAR SOLIDARITY AUSTRALIA IN ASIA, 1944–74 DAN HALVORSON Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760463236 ISBN (online): 9781760463243 WorldCat (print): 1126581099 WorldCat (online): 1126581312 DOI: 10.22459/CRCWS.2019 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover image courtesy of the National Archives of Australia. NAA: A1775, RGM107. This edition © 2019 ANU Press Contents Acknowledgements . vii Abbreviations . ix 1 . Introduction . 1 2 . Region and regionalism in the immediate postwar period . 13 3 . Decolonisation and Commonwealth responsibility . 43 4 . The Cold War and non‑communist solidarity in East Asia . 71 5 . The winds of change . 103 6 . Outside the margins . 131 7 . Conclusion . 159 References . 167 Index . 185 Acknowledgements I would like to thank Cathy Moloney, Anja Mustafic, Jennifer Roberts and Lucy West for research assistance on this project. Thanks also to my colleagues Michael Heazle, Andrew O’Neil, Wes Widmaier, Ian Hall, Jason Sharman and Lucy West for reading and commenting on parts of the work. Additionally, I would like to express my gratitude to participants at the 15th International Conference of Australian Studies in China, held at Peking University, Beijing, 8–10 July 2016, and participants at the Seventh Annual Australia–Japan Dialogue, hosted by the Griffith Asia Institute and Japan Institute for International Affairs, held in Brisbane, 9 November 2017, for useful comments on earlier papers contributing to the manuscript. -

Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism Mathias Risse

John F. Kennedy School of Government Harvard University Faculty Research Working Papers Series Can There be “Libertarianism without Inequality”? Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism Mathias Risse Nov 2003 RWP03-044 The views expressed in the KSG Faculty Research Working Paper Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the John F. Kennedy School of Government or Harvard University. All works posted here are owned and copyrighted by the author(s). Papers may be downloaded for personal use only. Can There be “Libertarianism without Inequality”? Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism1 Mathias Risse John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University October 25, 2003 1. Left-libertarianism is not a new star on the sky of political philosophy, but it was through the recent publication of Peter Vallentyne and Hillel Steiner’s anthologies that it became clearly visible as a contemporary movement with distinct historical roots. “Left- libertarian theories of justice,” says Vallentyne, “hold that agents are full self-owners and that natural resources are owned in some egalitarian manner. Unlike most versions of egalitarianism, left-libertarianism endorses full self-ownership, and thus places specific limits on what others may do to one’s person without one’s permission. Unlike right- libertarianism, it holds that natural resources may be privately appropriated only with the permission of, or with a significant payment to, the members of society. Like right- libertarianism, left-libertarianism holds that the basic rights of individuals are ownership rights. Left-libertarianism is promising because it coherently underwrites both some demands of material equality and some limits on the permissible means of promoting this equality” (Vallentyne and Steiner (2000a), p 1; emphasis added). -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

'Where We Would Extend the Moral

‘WHERE WE WOULD EXTEND THE MORAL POWER OF OUR CIVILIZATION’: AMERICAN CULTURAL AND POLITICAL FOREIGN RELATIONS WITH CHINA, 1843-1856 A dissertation submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Mathew T. Brundage December 2015 © Copyright All rights reserved Except for previously published materials Dissertation written by Mathew T. Brundage B.A., Capital University, 2005 M.A., Kent State University, 2007 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2015 Approved by ________________________________ Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Mary Ann Heiss, Ph.D. ________________________________ Kevin Adams, Ph.D. ________________________________ Gang Zhao, Ph.D. ________________________________ James Tyner, Ph.D. Accepted by ________________________________ Chair, Department of History Kenneth Bindas, Ph.D. ________________________________ Dean, College of Arts and Sciences James L. Blank, Ph.D. TABLE OF CONTENTS………………………………………………….. iii LIST OF FIGURES………………………………………………………... iv PREFACE ………………………………………………………………... vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………….. vii INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………… 1 CHAPTERS I. Chapter 1: China as Mystery ……………………………… 30 II. Chapter 2: China as Opportunity ..………………………… 84 III. Chapter 3: China as a Flawed Empire………………………146 IV. Chapter 4: China as a Threat ………………………………. 217 V. Chapter 5: Redefining “Success” in the Sino-American Relationship ……………………………………………….. 274 CONCLUSION…………………………………………………………….. 317 APPENDIX………………………………………………………………… 323 BIBLIOGRAPHY…………………………………………………………. -

Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution

Class, Race and Corporate Power Volume 9 Issue 1 Article 2 2021 Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution Chris Wright [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Wright, Chris (2021) "Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution," Class, Race and Corporate Power: Vol. 9 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. DOI: 10.25148/CRCP.9.1.009647 Available at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower/vol9/iss1/2 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts, Sciences & Education at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Class, Race and Corporate Power by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution Abstract In the twenty-first century, it is time that Marxists updated the conception of socialist revolution they have inherited from Marx, Engels, and Lenin. Slogans about the “dictatorship of the proletariat” “smashing the capitalist state” and carrying out a social revolution from the commanding heights of a reconstituted state are completely obsolete. In this article I propose a reconceptualization that accomplishes several purposes: first, it explains the logical and empirical problems with Marx’s classical theory of revolution; second, it revises the classical theory to make it, for the first time, logically consistent with the premises of historical materialism; third, it provides a (Marxist) theoretical grounding for activism in the solidarity economy, and thus partially reconciles Marxism with anarchism; fourth, it accounts for the long-term failure of all attempts at socialist revolution so far. -

Solidarity the Adventures of a Concept Between Fact and Norm

1 Solidarity The Adventures of a Concept between Fact and Norm F ALL THE CONCEPTS that form the constellation of modern political Othought, surely “solidarity” is a strong candidate for the most chal- lenging. At once influential and undertheorized, the concept of solidarity appears to function across a startling range of discourses. At the core of the difficulties involved in using the concept of solidarity for illuminating contemporary political problems is an ambiguity between normative and descriptive uses of the concept itself. The goal of this introductory chapter is to offer a reconstruction, in part intellectual-historical and in part analytic, of the normative-descriptive ambiguity in our current usage of the concept of solidarity. This ambiguity between fact and norm shouldn’t be taken as an unfortunate outcome of a history of misinterpretations, or as an example of a muddy concept in need of clarification. Rather, we should view the fact-norm ambiguity as a dialectical tension, in the sense that a degree of undecidability between normative and descriptive moments (in Hegel’s sense) of solidarity is itself the core meaning of the term—a tension that can be turned to highly productive use, as the subsequent chapters will attempt. In contemporary political theory solidarity can be invoked as a synonym for community, as the political value against which the freedom of individ- uals must be balanced and without which freedom becomes hollow. In this context, solidarity effectively translates the eighteenth-century republican ideal of “fraternity,” intended as a sibling to the ideal political norms of lib- erty and equality. -

If Not Left-Libertarianism, Then What?

COSMOS + TAXIS If Not Left-Libertarianism, then What? A Fourth Way out of the Dilemma Facing Libertarianism LAURENT DOBUZINSKIS Department of Political Science Simon Fraser University 8888 University Drive Burnaby, B.C. Canada V5A 1S6 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.sfu.ca/politics/faculty/full-time/laurent_dobuzinskis.html Bio-Sketch: Laurent Dobuzinskis’ research is focused on the history of economic and political thought, with special emphasis on French political economy, the philosophy of the social sciences, and public policy analysis. Abstract: Can the theories and approaches that fall under the more or less overlapping labels “classical liberalism” or “libertarianism” be saved from themselves? By adhering too dogmatically to their principles, libertarians may have painted themselves into a corner. They have generally failed to generate broad political or even intellectual support. Some of the reasons for this isolation include their reluctance to recognize the multiplicity of ways order emerges in different contexts and, more 31 significantly, their unshakable faith in the virtues of free markets renders them somewhat blind to economic inequalities; their strict construction of property rights and profound distrust of state institutions leave them unable to recommend public policies that could alleviate such problems. The doctrine advanced by “left-libertarians” and market socialists address these substantive weaknesses in ways that are examined in detail in this paper. But I argue that these “third way” movements do not stand any better chance than libertari- + TAXIS COSMOS anism tout court to become a viable and powerful political force. The deeply paradoxical character of their ideas would make it very difficult for any party or leader to gain political traction by building an election platform on them. -

Property As Entrance

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 2005 Property as Entrance Eduardo Peñalver Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Eduardo Peñalver, "Property as Entrance," 91 Virginia Law Review 1889 (2005). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PROPERTY AS ENTRANCE Eduardo M. Pehalver* INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 1890 I. PROPERTY AS EXIT .................................................................... 1895 A. Strong and Weak Exit ......................................................... 1895 B. Freedom as the Absence of Coercion ................................ 1896 C. The Individual as Self-Sufficient ........................................ 1898 D. Community as Voluntary .................................................... 1900 E. DoctrinalInfluence of Property as Exit ............................ 1902 1. The Right to Exclude ..................................................... 1902 2. Takings Law .................................................................. 1905 II. Two CRITIQUES OF PROPERTY AS EXIT .................................. 1907 A. The Neo-Realist Critique of Property as Exit .................. -

Practices of Refugee Support Between Humanitarian Help And

Larissa Fleischmann Contested Solidarity Culture and Social Practice Larissa Fleischmann, born in 1989, works as a Postdoctoral Researcher in Human Geography at the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg. She received her PhD from the University of Konstanz, where she was a member of the Centre of Excellence »Cultural Foundations of Social Integration« and the Social and Cultu- ral Anthropology Research Group from 2014 to 2018. Larissa Fleischmann Contested Solidarity Practices of Refugee Support between Humanitarian Help and Political Activism Dissertation of the University of Konstanz Date of the oral examination: February 15, 2019 1st reviewer: Prof. Dr. Thomas G. Kirsch 2nd reviewer: PD Dr. Eva Youkhana 3rd reviewer: Prof. Dr. Judith Beyer This publication was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Re- search Foundation) - Project number 448887013. The author acknowledges the financial support of the Open Access Publication Fund of the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg. The field research for this publication was funded by the Centre of Excellence “Cultural Foundations of Social Integration”, University of Konstanz. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Na- tionalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 (BY- NC) license, which means that the text may be remixed, build upon and be distributed, provided credit is given to the author, but may not be used for commercial purposes. For details go to: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ Permission to use the text for commercial purposes can be obtained by contacting rights@ transcript-publishing.com Creative Commons license terms for re-use do not apply to any content (such as graphs, figures, photos, excerpts, etc.) not original to the Open Access publication and further permission may be required from the rights holder. -

Justice, Resistance and Solidarity – Race and Policing in England

Runnymede Perspectives Justice, Resistance and Solidarity Race and Policing in England and Wales Edited by Nadine El-Enany and Eddie Bruce-Jones Disclaimer Runnymede: This publication is part of the Runnymede Perspectives Intelligence for a series, the aim of which is to foment free and exploratory thinking on race, ethnicity and equality. The facts presented Multi-ethnic Britain and views expressed in this publication are, however, those of the individual authors and not necessariliy those of the Runnymede Trust. Runnymede is the UK’s leading independent thinktank ISBN: 978-1-909546-11-0 on race equality and race Published by Runnymede in October 2015, this document is relations. Through high- copyright © Runnymede 2015. Some rights reserved. quality research and thought leadership, we: Open access. Some rights reserved. The Runnymede Trust wants to encourage the circulation of its work as widely as possible while retaining the copyright. • Identify barriers to race The trust has an open access policy which enables anyone equality and good race to access its content online without charge. Anyone can download, save, perform or distribute this work in any relations; format, including translation, without written permission. • Provide evidence to This is subject to the terms of the Creative Commons support action for social Licence Deed: Attribution-Non-Commercial-No Derivative Works 2.0 UK: England & Wales. Its main conditions are: change; • Influence policy at all • You are free to copy, distribute, display and perform levels. the work; • You must give the original author credit; • You may not use this work for commercial purposes; • You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work.