Alasdair Macintyre and Trotskyism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

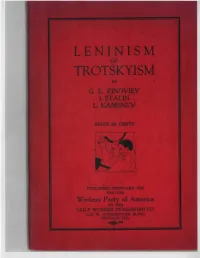

Leninism Or Trotskyism.Pdf

LENINISM TROTSKYISM BY G. E. ZINOVIEV I. STALIN L. KAMENEV PRICE 20 CENTS r PUBLISHED FEBRUARY 1925 FOR THE Workers Party of America BY THE DAILY WORKER PUBLISHING CO. 1113 W. WASHINGTON BLVD., CHICAGO, ILL. LENINISM OR TROTSKYISM BY G. E. ZINOVIEV I. STALIN L. KAMENEV PRICE 20 CENTS PUBLISHED FEBRUARY 1925 FOR THE Workers Party of America BY THE DAILY WORKER PUBLISHING CO. 1113 W. WASHINGTON BLVD.. CHICAGO. ILL. pllllllllllllllilllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllfllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllH | READY! I 1 To Fill Every Need of the American 1 1 Working Class for 1 | INFORMATION | | The Daily Worker Publishing Co. | | 1113 W. Washington Blvd., | | Chicago, 111. i S Publishers of: H 1 THE DAILY WORKER, contains the news of the world | = of labor. It is the world's only Communist daily appearing j| j£ in English. It is the only daily in America that fights for the = = interests of the working class. Participants of the struggle ^ 5 against capitalism find the DAILY WORKER indispensable ji 5 for its information and its leadership. || j SUBSCRIPTION RATES: I = 1 year—$6.00; 6 mos.—$3.50; Smos.—$2.00. |j 5 In Chicago: = 1 1 year—$8.00; 6 mos.—$4.50; 3 mos.—$2.50. = 1 THE WORKERS MONTHLY as the official organ of the | j= Workers Party and the Trade Union Educational League re- s S fleets the struggles of the American working class againsj 5 5 capitalism. Every month are printed the, best contributions =j = to American working class art and literature together witt 5 £j theoretical and descriptive articles on timely labor subjects = j= by the leading figures of the American and International = §= Communist movement. -

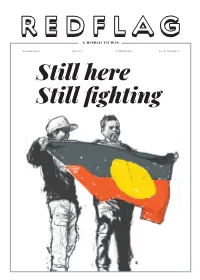

RF177.Pdf (Redflag.Org.Au)

A WORLD TO WIN REDFLAG.ORG.AU ISSUE #177 19 JANUARY 2021 $3 / $5 (SOLIDARITY) Still here Still fi ghting REDFLAG | 19 JANUARY 2021 PUBLICATION OF SOCIALIST ALTERNATIVE REDFLAG.ORG.AU 2 Red Flag Issue # 177 19 January 2021 ISSN: 2202-2228 Published by Red Flag Support the Press Inc. Trades Hall 54 Victoria St Carlton South Vic 3053 [email protected] Christmas Island (03) 9650 3541 Editorial committee Ben Hillier Louise O’Shea Daniel Taylor Corey Oakley rioters James Plested Simone White fail nonetheless. Some are forced to complete rehabil- Visual editor itation programs and told that when they do so their James Plested appeals will be strengthened. They do it. They fail. These are men with families in Australia. They Production are workers who were raising children. They are men Tess Lee Ack n the first week of 2021, detainees at the Christ- who were sending money to impoverished family Allen Myers mas Island Immigration Detention Centre be- members in other countries. Now, with their visas can- Oscar Sterner gan setting it alight. A peaceful protest, which celled, they have no incomes at all. This has rendered Subscriptions started on the afternoon of 5 January, had by partners and children homeless. and publicity evening escalated into a riot over the treatment Before their transportation from immigration fa- Jess Lenehan Iof hundreds of men there by Home Affairs Minister cilities and prisons on the Australian mainland, some Peter Dutton and his Australian Border Force. Four of these men could receive visits from loved ones. Now What is days later, facing down reinforced numbers of masked, they can barely, if at all, get internet access to speak to armed Serco security thugs and Australian Federal them. -

Marx, Historical Materialism and the Asiatic Wde Of

MARX, HISTORICAL MATERIALISM AND THE ASIATIC WDE OF PRODUCTION BY Joseph Bensdict Huang Tan B.A. (Honors) Simon Fraser University 1994 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULLFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THE SCHOOL OF COMMUN ICATION @Joseph B. Tan 2000 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY July 2000 Al1 rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. uisitions and Acguiiiet raphii Senrices senrices bibiiihiques The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Li'brary of Canada to BibIiothèque nationale du Canada de reproduceYloan, distriiute or sel1 reproduireyprêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microh, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous papa or electronic formats. la fome de micro fi ch el^ de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author tetains ownership of the L'auîeur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis*Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts iÏom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT Historical materialism (HM), the theory of history originally developed by Marx and Engels is most comrnonly interpreted as a unilinear model, which dictates that al1 societies must pass through definite and universally similar stages on the route to communism. This simplistic interpretation existed long before Stalin and has persisted long after the process of de-Stalinization and into the present. -

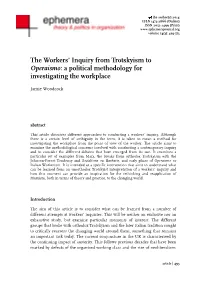

The Workers' Inquiry from Trotskyism to Operaismo

the author(s) 2014 ISSN 1473-2866 (Online) ISSN 2052-1499 (Print) www.ephemerajournal.org volume 14(3): 493-513 The Workers’ Inquiry from Trotskyism to Operaismo: a political methodology for investigating the workplace Jamie Woodcock abstract This article discusses different approaches to conducting a workers’ inquiry. Although there is a certain level of ambiguity in the term, it is taken to mean a method for investigating the workplace from the point of view of the worker. The article aims to examine the methodological concerns involved with conducting a contemporary inquiry and to consider the different debates that have emerged from its use. It examines a particular set of examples from Marx, the breaks from orthodox Trotskyism with the Johnson-Forest Tendency and Socialisme ou Barbarie, and early phase of Operaismo or Italian Workerism. It is intended as a specific intervention that aims to understand what can be learned from an unorthodox Trotskyist interpretation of a workers’ inquiry and how this moment can provide an inspiration for the rethinking and reapplication of Marxism, both in terms of theory and practice, to the changing world. Introduction The aim of this article is to consider what can be learned from a number of different attempts at workers’ inquiries. This will be neither an exclusive nor an exhaustive study, but examine particular moments of interest. The different groups that broke with orthodox Trotskyism and the later Italian tradition sought to critically reassess the changing world around them, something that remains an important task today. The current conjuncture in the UK is characterised by the continuing impact of austerity. -

Commonwealth Responsibility and Cold War Solidarity Australia in Asia, 1944–74

COMMONWEALTH RESPONSIBILITY AND COLD WAR SOLIDARITY AUSTRALIA IN ASIA, 1944–74 COMMONWEALTH RESPONSIBILITY AND COLD WAR SOLIDARITY AUSTRALIA IN ASIA, 1944–74 DAN HALVORSON Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760463236 ISBN (online): 9781760463243 WorldCat (print): 1126581099 WorldCat (online): 1126581312 DOI: 10.22459/CRCWS.2019 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover image courtesy of the National Archives of Australia. NAA: A1775, RGM107. This edition © 2019 ANU Press Contents Acknowledgements . vii Abbreviations . ix 1 . Introduction . 1 2 . Region and regionalism in the immediate postwar period . 13 3 . Decolonisation and Commonwealth responsibility . 43 4 . The Cold War and non‑communist solidarity in East Asia . 71 5 . The winds of change . 103 6 . Outside the margins . 131 7 . Conclusion . 159 References . 167 Index . 185 Acknowledgements I would like to thank Cathy Moloney, Anja Mustafic, Jennifer Roberts and Lucy West for research assistance on this project. Thanks also to my colleagues Michael Heazle, Andrew O’Neil, Wes Widmaier, Ian Hall, Jason Sharman and Lucy West for reading and commenting on parts of the work. Additionally, I would like to express my gratitude to participants at the 15th International Conference of Australian Studies in China, held at Peking University, Beijing, 8–10 July 2016, and participants at the Seventh Annual Australia–Japan Dialogue, hosted by the Griffith Asia Institute and Japan Institute for International Affairs, held in Brisbane, 9 November 2017, for useful comments on earlier papers contributing to the manuscript. -

The Personal, the Political, and Permanent Revolution: Ernest Mandel and the Conflicted Legacies of Trotskyism*

IRSH 55 (2010), pp. 117–132 doi:10.1017/S0020859009990642 r 2010 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis REVIEW ESSAY The Personal, the Political, and Permanent Revolution: Ernest Mandel and the Conflicted Legacies of Trotskyism* B RYAN D. PALMER Canadian Studies, Trent University, Traill College E-mail: [email protected] JAN WILLEM STUTJE. Ernest Mandel: A Rebel’s Dream Deferred. Verso, London [etc.] 2009. 460 pp. $34.95. Biographies of revolutionary Marxists should not be written by the faint of heart. The difficulties are daunting. Which revolutionary tradition is to be given pride of place? Of many Marxisms, which will be extolled, which exposed? What balance will be struck between the personal and the political, a dilemma that cannot be avoided by those who rightly place analytic weight on the public life of organizations and causes and yet understand, as well, how private experience affects not only the individual but the movements, ideas, and developments he or she influenced. Social history’s accent on the particular and its elaboration of context, political biography’s attention to structures, institutions, and debates central to an individual’s life, and intellectual history’s close examination of central ideas and the complexities of their refinement present a trilogy of challenge for any historian who aspires to write the life of someone who was both in history and dedicated to making his- tory. Ernest Mandel was just such a someone, an exceedingly important and troublingly complex figure. * The author thanks Tom Reid, Murray Smith, and Paul Le Blanc for reading an earlier draft of this review, and offering suggestions for revision. -

The Bolshevil{S and the Chinese Revolution 1919-1927 Chinese Worlds

The Bolshevil{s and the Chinese Revolution 1919-1927 Chinese Worlds Chinese Worlds publishes high-quality scholarship, research monographs, and source collections on Chinese history and society from 1900 into the next century. "Worlds" signals the ethnic, cultural, and political multiformity and regional diversity of China, the cycles of unity and division through which China's modern history has passed, and recent research trends toward regional studies and local issues. It also signals that Chineseness is not contained within territorial borders overseas Chinese communities in all countries and regions are also "Chinese worlds". The editors see them as part of a political, economic, social, and cultural continuum that spans the Chinese mainland, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macau, South East Asia, and the world. The focus of Chinese Worlds is on modern politics and society and history. It includes both history in its broader sweep and specialist monographs on Chinese politics, anthropology, political economy, sociology, education, and the social science aspects of culture and religions. The Literary Field of New Fourth Artny Twentieth-Century China Communist Resistance along the Edited by Michel Hockx Yangtze and the Huai, 1938-1941 Gregor Benton Chinese Business in Malaysia Accumulation, Ascendance, A Road is Made Accommodation Communism in Shanghai 1920-1927 Edmund Terence Gomez Steve Smith Internal and International Migration The Bolsheviks and the Chinese Chinese Perspectives Revolution 1919-1927 Edited by Frank N Pieke and Hein Mallee -

Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution

Class, Race and Corporate Power Volume 9 Issue 1 Article 2 2021 Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution Chris Wright [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Wright, Chris (2021) "Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution," Class, Race and Corporate Power: Vol. 9 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. DOI: 10.25148/CRCP.9.1.009647 Available at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower/vol9/iss1/2 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts, Sciences & Education at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Class, Race and Corporate Power by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution Abstract In the twenty-first century, it is time that Marxists updated the conception of socialist revolution they have inherited from Marx, Engels, and Lenin. Slogans about the “dictatorship of the proletariat” “smashing the capitalist state” and carrying out a social revolution from the commanding heights of a reconstituted state are completely obsolete. In this article I propose a reconceptualization that accomplishes several purposes: first, it explains the logical and empirical problems with Marx’s classical theory of revolution; second, it revises the classical theory to make it, for the first time, logically consistent with the premises of historical materialism; third, it provides a (Marxist) theoretical grounding for activism in the solidarity economy, and thus partially reconciles Marxism with anarchism; fourth, it accounts for the long-term failure of all attempts at socialist revolution so far. -

Solidarity: Reflections on an Emerging Concept in Bioethics

Solidarity: reflections on an emerging concept in bioethics Barbara Prainsack and Alena Buyx This report was commissioned by the Nuffield Council on Bioethics (NCoB) and was jointly funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) and the Nuffield Foundation. The award was managed by the Economic and Social Research Council on behalf of the partner organisations, and some additional funding was made available by NCoB. For the duration of six months in 2011, Professor Barbara Prainsack was the NCoB Solidarity Fellow, working closely with fellow author Dr Alena Buyx, Assistant Director of NCoB. Disclaimer The report, whilst funded jointly by the AHRC, the Nuffield Foundation and NCoB, does not necessarily express the views and opinions of these organisations; all views expressed are those of the authors, Professor Barbara Prainsack and Dr Alena Buyx. The Nuffield Council on Bioethics is an independent body that examines and reports on ethical issues in biology and medicine. It is funded jointly by the Nuffield Foundation, the Wellcome Trust and the Medical Research Council, and has gained an international reputation for advising policy makers and stimulating debate in bioethics. www.nuffieldbioethics.org The Nuffield Foundation is an endowed charitable trust that aims to improve social wellbeing in the widest sense. It funds research and innovation in education and social policy and also works to build capacity in education, science and social science research. www.nuffieldfoundation.org Established in April 2005, the AHRC is a non-Departmental public body. It supports world-class research that furthers our understanding of human culture and creativity. www.ahrc.ac.uk © Barbara Prainsack and Alena Buyx ISBN: 978-1-904384-25-0 November 2011 Printed in the UK by ESP Colour Ltd. -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://eprints.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Lenin and the Iskra Faction of the RSDLP 1899-1903 Richard Mullin Doctor of Philosophy Resubmission University of Sussex March 2010 1 I hereby declare that this thesis has not been submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree ……………………………….. 2 Contents Contents.......................................................................................................................3 Acknowledgements……………..…………………………………………………...4 Abstract........................................................................................................................5 Notes on Names, Texts and Dates…….....……………………..…………………...6 Chapter One: Historical and Historiographical Context…………………..…....7 i) 1899-1903 in the Context of Russian Social-Democratic History and Theory …12 ii) Historiographical Trends in the Study of Lenin and the RSDLP …………...…..23 iii) How the thesis develops -

Joseph Hansen Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf78700585 No online items Register of the Joseph Hansen papers Finding aid prepared by Joseph Hansen Hoover Institution Archives 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA, 94305-6003 (650) 723-3563 [email protected] © 1998, 2006, 2012 Register of the Joseph Hansen 92035 1 papers Title: Joseph Hansen papers Date (inclusive): 1887-1980 Collection Number: 92035 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 109 manuscript boxes, 1 oversize box, 3 envelopes, 1 audio cassette(46.2 linear feet) Abstract: Speeches and writings, correspondence, notes, minutes, reports, internal bulletins, resolutions, theses, printed matter, sound recording, and photographs relating to Leon Trotsky, activities of the Socialist Workers Party in the United States, and activities of the Fourth International in Latin America, Western Europe and elsewhere. Physical Location: Hoover Institution Archives Creator: Hansen, Joseph, Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Archives. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Joseph Hansen papers, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Archives in 1992. Accruals Materials may have been added to the collection since this finding aid was prepared. To determine if this has occurred, find the collection in Stanford University's online catalog at http://searchworks.stanford.edu . Materials have been added to the collection if the number of boxes listed in the online catalog is larger than the number of boxes listed in this finding aid. -

Practices of Refugee Support Between Humanitarian Help And

Larissa Fleischmann Contested Solidarity Culture and Social Practice Larissa Fleischmann, born in 1989, works as a Postdoctoral Researcher in Human Geography at the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg. She received her PhD from the University of Konstanz, where she was a member of the Centre of Excellence »Cultural Foundations of Social Integration« and the Social and Cultu- ral Anthropology Research Group from 2014 to 2018. Larissa Fleischmann Contested Solidarity Practices of Refugee Support between Humanitarian Help and Political Activism Dissertation of the University of Konstanz Date of the oral examination: February 15, 2019 1st reviewer: Prof. Dr. Thomas G. Kirsch 2nd reviewer: PD Dr. Eva Youkhana 3rd reviewer: Prof. Dr. Judith Beyer This publication was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Re- search Foundation) - Project number 448887013. The author acknowledges the financial support of the Open Access Publication Fund of the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg. The field research for this publication was funded by the Centre of Excellence “Cultural Foundations of Social Integration”, University of Konstanz. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Na- tionalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 (BY- NC) license, which means that the text may be remixed, build upon and be distributed, provided credit is given to the author, but may not be used for commercial purposes. For details go to: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ Permission to use the text for commercial purposes can be obtained by contacting rights@ transcript-publishing.com Creative Commons license terms for re-use do not apply to any content (such as graphs, figures, photos, excerpts, etc.) not original to the Open Access publication and further permission may be required from the rights holder.