Commonwealth Responsibility and Cold War Solidarity Australia in Asia, 1944–74

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

When Australia Said NO! Fifteen Years Ago, the Australian People Turned Down the Menzies Govt's Bid to Shackle Democracy

„ By ERNIE CAMPBELL When Australia said NO! Fifteen years ago, the Australian people turned down the Menzies Govt's bid to shackle democracy. gE PT E M B E R . 22 is the 15th Anniversary of the defeat of the Menzies Government’s attempt, by referendum, to obtain power to suppress the Communist Party. Suppression of communism is a long-standing plank in the platform of the Liberal Party. The election of the Menzies Government in December 1949 coincided with America’s stepping-up of the “Cold War”. the Communist Party an unlawful association, to dissolve it, Chairmanship of Senator Joseph McCarthy, was engaged in an orgy of red-baiting, blackmail and intimidation. This was the situation when Menzies, soon after taking office, visited the United States to negotiate a big dollar loan. On his return from America, Menzies dramatically proclaimed that Australia had to prepare for war “within three years”. T o forestall resistance to the burdens and dangers involved in this, and behead the people’s movement of militant leadership, Menzies, in April 1950, introduced a Communist Party Dis solution Bill in the Federal Parliament. T h e Bill commenced with a series o f recitals accusing the Communist Party of advocating seizure of power by a minority through violence, intimidation and fraudulent practices, of being engaged in espionage activities, of promoting strikes for pur poses of sabotage and the like. Had there been one atom of truth in these charges, the Government possessed ample powers under the Commonwealth Crimes Act to launch an action against the Communist Party. -

The Removal of Whitlam

MAKING A DEMOCRACY to run things, any member could turn up to its meetings to listen and speak. Of course all members cannot participate equally in an org- anisation, and organisations do need leaders. The hopes of these reformers could not be realised. But from these times survives the idea that any governing body should consult with the people affected by its decisions. Local councils and governments do this regularly—and not just because they think it right. If they don’t consult, they may find a demonstration with banners and TV cameras outside their doors. The opponents of democracy used to say that interests had to be represented in government, not mere numbers of people. Democrats opposed this view, but modern democracies have to some extent returned to it. When making decisions, governments consult all those who have an interest in the matter—the stake- holders, as they are called. The danger in this approach is that the general interest of the citizens might be ignored. The removal of Whitlam The Labor Party captured the mood of the 1960s in its election campaign of 1972, with its slogan ‘It’s Time’. The Liberals had been in power for 23 years, and Gough Whitlam said it was time for a change, time for a fresh beginning, time to do things differently. Whitlam’s government was in tune with the times because it was committed to protecting human rights, to setting up an ombuds- man and to running an open government where there would be freedom of information. But in one thing Whitlam was old- fashioned: he believed in the original Labor idea of democracy. -

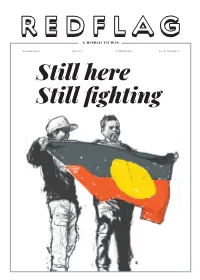

RF177.Pdf (Redflag.Org.Au)

A WORLD TO WIN REDFLAG.ORG.AU ISSUE #177 19 JANUARY 2021 $3 / $5 (SOLIDARITY) Still here Still fi ghting REDFLAG | 19 JANUARY 2021 PUBLICATION OF SOCIALIST ALTERNATIVE REDFLAG.ORG.AU 2 Red Flag Issue # 177 19 January 2021 ISSN: 2202-2228 Published by Red Flag Support the Press Inc. Trades Hall 54 Victoria St Carlton South Vic 3053 [email protected] Christmas Island (03) 9650 3541 Editorial committee Ben Hillier Louise O’Shea Daniel Taylor Corey Oakley rioters James Plested Simone White fail nonetheless. Some are forced to complete rehabil- Visual editor itation programs and told that when they do so their James Plested appeals will be strengthened. They do it. They fail. These are men with families in Australia. They Production are workers who were raising children. They are men Tess Lee Ack n the first week of 2021, detainees at the Christ- who were sending money to impoverished family Allen Myers mas Island Immigration Detention Centre be- members in other countries. Now, with their visas can- Oscar Sterner gan setting it alight. A peaceful protest, which celled, they have no incomes at all. This has rendered Subscriptions started on the afternoon of 5 January, had by partners and children homeless. and publicity evening escalated into a riot over the treatment Before their transportation from immigration fa- Jess Lenehan Iof hundreds of men there by Home Affairs Minister cilities and prisons on the Australian mainland, some Peter Dutton and his Australian Border Force. Four of these men could receive visits from loved ones. Now What is days later, facing down reinforced numbers of masked, they can barely, if at all, get internet access to speak to armed Serco security thugs and Australian Federal them. -

The Secret History of Australia's Nuclear Ambitions

Jim Walsh SURPRISE DOWN UNDER: THE SECRET HISTORY OF AUSTRALIAS NUCLEAR AMBITIONS by Jim Walsh Jim Walsh is a visiting scholar at the Center for Global Security Research at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. He is also a Ph.D. candidate in the Political Science program at MIT, where he is completing a dissertation analyzing comparative nuclear decisionmaking in Australia, the Middle East, and Europe. ustralia is widely considered tactical nuclear weapons. In 1961, of state behavior and the kinds of Ato be a world leader in ef- Australia proposed a secret agree- policies that are most likely to retard forts to halt and reverse the ment for the transfer of British the spread of nuclear weapons? 1 spread of nuclear weapons. The nuclear weapons, and, throughout This article attempts to answer Australian government created the the 1960s, Australia took actions in- some of these questions by examin- Canberra Commission, which called tended to keep its nuclear options ing two phases in Australian nuclear for the progressive abolition of open. It was not until 1973, when history: 1) the attempted procure- nuclear weapons. It led the fight at Australia ratified the NPT, that the ment phase (1956-1963); and 2) the the U.N. General Assembly to save country finally renounced the acqui- indigenous capability phase (1964- the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty sition of nuclear weapons. 1972). The historical reconstruction (CTBT), and the year before, played Over the course of four decades, of these events is made possible, in a major role in efforts to extend the Australia has gone from a country part, by newly released materials Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of that once sought nuclear weapons to from the Australian National Archive Nuclear Weapons (NPT) indefi- one that now supports their abolition. -

Does the Media Fail Aboriginal Political Aspirations?

DOES THE MEDIA 45 years of news media reporting of FAIL ABORIGINAL key political moments POLITICAL Amy Thomas Andrew Jakubowicz ASPIRATIONS? Heidi Norman AIATSIS Research Publications DOES THE MEDIA FAIL ABORIGINAL POLITICAL ASPIRATIONS? 45 years of news media reporting of key political moments Amy Thomas Andrew Jakubowicz Heidi Norman DOES THE MEDIA FAIL ABORIGINAL POLITICAL ASPIRATIONS? First published in 2019 by Aboriginal Studies Press Copyright @ New South Wales Government All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by an information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing form the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, which ever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its education purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act. The opinions expressed in this book are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the view of AIATSIS or ASP. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are respectfully advised that this publication contains names and images of deceased persons and culturally sensitive information. ISBN: 9780855750848 (pb) ISBN: 9780855750855 (ePub) ISBN: 9780855750862 (kindle) ISBN: 9780855750930 (ebook PDF) Printed in Australia by Ligare Design and Typsetting by 33 Creative Cover image: Tessa Ferguson and Edwin Jangalaros presenting the Larrakia petition outside Government House, Darwin. The petition was 3.3 metres long, featuring one thousand signatures and thumbprints collected by Gwalwa Daraniki. -

Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution

Class, Race and Corporate Power Volume 9 Issue 1 Article 2 2021 Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution Chris Wright [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Wright, Chris (2021) "Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution," Class, Race and Corporate Power: Vol. 9 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. DOI: 10.25148/CRCP.9.1.009647 Available at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/classracecorporatepower/vol9/iss1/2 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts, Sciences & Education at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Class, Race and Corporate Power by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Marxism and the Solidarity Economy: Toward a New Theory of Revolution Abstract In the twenty-first century, it is time that Marxists updated the conception of socialist revolution they have inherited from Marx, Engels, and Lenin. Slogans about the “dictatorship of the proletariat” “smashing the capitalist state” and carrying out a social revolution from the commanding heights of a reconstituted state are completely obsolete. In this article I propose a reconceptualization that accomplishes several purposes: first, it explains the logical and empirical problems with Marx’s classical theory of revolution; second, it revises the classical theory to make it, for the first time, logically consistent with the premises of historical materialism; third, it provides a (Marxist) theoretical grounding for activism in the solidarity economy, and thus partially reconciles Marxism with anarchism; fourth, it accounts for the long-term failure of all attempts at socialist revolution so far. -

Solidarity: Reflections on an Emerging Concept in Bioethics

Solidarity: reflections on an emerging concept in bioethics Barbara Prainsack and Alena Buyx This report was commissioned by the Nuffield Council on Bioethics (NCoB) and was jointly funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) and the Nuffield Foundation. The award was managed by the Economic and Social Research Council on behalf of the partner organisations, and some additional funding was made available by NCoB. For the duration of six months in 2011, Professor Barbara Prainsack was the NCoB Solidarity Fellow, working closely with fellow author Dr Alena Buyx, Assistant Director of NCoB. Disclaimer The report, whilst funded jointly by the AHRC, the Nuffield Foundation and NCoB, does not necessarily express the views and opinions of these organisations; all views expressed are those of the authors, Professor Barbara Prainsack and Dr Alena Buyx. The Nuffield Council on Bioethics is an independent body that examines and reports on ethical issues in biology and medicine. It is funded jointly by the Nuffield Foundation, the Wellcome Trust and the Medical Research Council, and has gained an international reputation for advising policy makers and stimulating debate in bioethics. www.nuffieldbioethics.org The Nuffield Foundation is an endowed charitable trust that aims to improve social wellbeing in the widest sense. It funds research and innovation in education and social policy and also works to build capacity in education, science and social science research. www.nuffieldfoundation.org Established in April 2005, the AHRC is a non-Departmental public body. It supports world-class research that furthers our understanding of human culture and creativity. www.ahrc.ac.uk © Barbara Prainsack and Alena Buyx ISBN: 978-1-904384-25-0 November 2011 Printed in the UK by ESP Colour Ltd. -

William Mcmahon: the First Treasurer with an Economics Degree

William McMahon: the first Treasurer with an economics degree John Hawkins1 William McMahon was Australia’s first treasurer formally trained in economics. He brought extraordinary energy to the role. The economy performed strongly during McMahon’s tenure, although there are no major reforms to his name, and arguably pressures were allowed to build which led to the subsequent inflation of the 1970s. Never popular with his cabinet colleagues, McMahon’s public reputation was tarnished by his subsequent unsuccessful period as prime minister. Source: National Library of Australia.2 1 The author formerly worked in the Domestic Economy Division, the Australian Treasury. This article has benefited from comments provided by Selwyn Cornish and Ian Hancock but responsibility lies with the author and the views are not necessarily those of Treasury. 83 William McMahon: the first treasurer with an economics degree Introduction Sir William McMahon is now recalled by the public, if at all, for accompanying his glamorous wife to the White House in a daringly revealing outfit (hers not his). Comparisons invariably place him as one of the weakest of the Australian prime ministers.3 Indeed, McMahon himself recalled it as ‘a time of total unpleasantness’.4 His reputation as treasurer is much better, being called ‘by common consent a remarkably good one’.5 The economy performed well during his tenure, but with the global economy strong and no major shocks, this was probably more good luck than good management.6 His 21 years and four months as a government minister, across a range of portfolios, was the third longest (and longest continuously serving) in Australian history.7 In his younger days he was something of a renaissance man; ‘a champion ballroom dancer, an amateur boxer and a good squash player — all of which require, like politics, being fast on his feet’.8 He suffered deafness until it was partly cured by some 2 ‘Portrait of William McMahon, Prime Minister of Australia from 1971-1972/Australian Information Service’, Bib ID: 2547524. -

Odgers' Australian Senate Practice

Chapter 21 RELATIONS WITH THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES N A BICAMERAL SYSTEM the conduct of relations between the two houses of the legislature is of I considerable significance, particularly as the houses must reach full agreement on proposed legislation before it can go forward into law, and action on other matters also depends on the houses coming to agreement. In practice, under the system of government as it has developed in Australia, relations between the two Houses are relations between the Senate and the executive government, as the latter, through its control of a disciplined party majority, controls the House of Representatives. This chapter could well have been combined with Chapter 19, Relations with the Executive Government. There is value, however, in treating the matter on the basis of the constitutional assumption of dealings between two representative assemblies, as this pattern may in certain circumstances, for example, a government in a minority in the House, reassert itself. The Constitution contains some provisions regulating relations between the Houses: • section 53 provides some rules relating to proceedings on legislation • section 57 provides for the resolution of certain disagreements between the Houses in relation to proposed legislation by simultaneous dissolutions of the Houses. The rules contained in section 53 are dealt with in Chapter 12, Legislation, and Chapter 13, Financial Legislation. Simultaneous dissolutions under section 57 are dealt with in this chapter. The standing orders of the Senate provide more detailed rules for the conduct of relations between the Houses, particularly in relation to legislation. In so far as these rules regulate relations between the Houses generally, they are also dealt with in this chapter, and in so far as they relate to legislation they are dealt with in more detail in chapters 12 and 13. -

ACHIEVEMENT and SHORTFALL in the NARCISSISTIC LEADER Gough Whitlam and Australian Politics

CHAPTER 12 ACHIEVEMENT AND SHORTFALL IN THE NARCISSISTIC LEADER Gough Whitlam and Australian Politics JAMES A. WALTER Conservative parties have dominated Australian federal politics since the Second World War. Coming to power in 1949 under Mr. (later Sir) Robert Menzies, the Liberal-Country party (L-CP) coalition held office continuously until 1972, when it was displaced by the reformist Aus tralian Labor party (ALP) government of Mr. Gough Whitlam. Yet the Whitlam ALP government served for only three years before losing office in unusual and controversial circumstances in 1975, since which time the conservative coalition has again held sway. It is my purpose here to examine the leadership of Gough Whitlam and the effects he had upon the fortunes of the ALP government. But first, it is essential to sketch briefly the political history of the years before Whitlam carne to power and the material conditions which the ALP administration en countered, for rarely can the success or failure of an administration be attributed solely to the qualities of an individual. In this case, the con tingencies of situation and history were surely as relevant as the charac teristics of leadership. In Australia, the period from the late 1940s until the late 1960s was, in relative terms, a time of plenty. Prices for Australian exports (agri cultural and later mineral products) were high, foreign investment in the economy flourished, and Robert Menzies' conservative government capitalized by astutely presenting itself as the beneficent author of these conditions. In reality, the government played little part, and develop- 231 C. B. Strozier et al. -

Practices of Refugee Support Between Humanitarian Help And

Larissa Fleischmann Contested Solidarity Culture and Social Practice Larissa Fleischmann, born in 1989, works as a Postdoctoral Researcher in Human Geography at the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg. She received her PhD from the University of Konstanz, where she was a member of the Centre of Excellence »Cultural Foundations of Social Integration« and the Social and Cultu- ral Anthropology Research Group from 2014 to 2018. Larissa Fleischmann Contested Solidarity Practices of Refugee Support between Humanitarian Help and Political Activism Dissertation of the University of Konstanz Date of the oral examination: February 15, 2019 1st reviewer: Prof. Dr. Thomas G. Kirsch 2nd reviewer: PD Dr. Eva Youkhana 3rd reviewer: Prof. Dr. Judith Beyer This publication was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Re- search Foundation) - Project number 448887013. The author acknowledges the financial support of the Open Access Publication Fund of the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg. The field research for this publication was funded by the Centre of Excellence “Cultural Foundations of Social Integration”, University of Konstanz. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Na- tionalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 (BY- NC) license, which means that the text may be remixed, build upon and be distributed, provided credit is given to the author, but may not be used for commercial purposes. For details go to: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ Permission to use the text for commercial purposes can be obtained by contacting rights@ transcript-publishing.com Creative Commons license terms for re-use do not apply to any content (such as graphs, figures, photos, excerpts, etc.) not original to the Open Access publication and further permission may be required from the rights holder. -

House of Representatives By-Elections 1902-2002

INFORMATION, ANALYSIS AND ADVICE FOR THE PARLIAMENT INFORMATION AND RESEARCH SERVICES Current Issues Brief No. 15 2002–03 House of Representatives By-elections 1901–2002 DEPARTMENT OF THE PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY ISSN 1440-2009 Copyright Commonwealth of Australia 2003 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent of the Department of the Parliamentary Library, other than by Senators and Members of the Australian Parliament in the course of their official duties. This paper has been prepared for general distribution to Senators and Members of the Australian Parliament. While great care is taken to ensure that the paper is accurate and balanced, the paper is written using information publicly available at the time of production. The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Information and Research Services (IRS). Advice on legislation or legal policy issues contained in this paper is provided for use in parliamentary debate and for related parliamentary purposes. This paper is not professional legal opinion. Readers are reminded that the paper is not an official parliamentary or Australian government document. IRS staff are available to discuss the paper's contents with Senators and Members and their staff but not with members of the public. Published by the Department of the Parliamentary Library, 2003 I NFORMATION AND R ESEARCH S ERVICES Current Issues Brief No. 15 2002–03 House of Representatives By-elections 1901–2002 Gerard Newman, Statistics Group Scott Bennett, Politics and Public Administration Group 3 March 2003 Acknowledgments The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of Murray Goot, Martin Lumb, Geoff Winter, Jan Pearson, Janet Wilson and Diane Hynes in producing this paper.