THE RATIONALE for POL POT's DEMOCRATIC KAMPUCHEA By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNSC Play Their Part

HASMUN’19 STUDY GUIDE The United Nations Security Council Khmer Rouge’s Cambodia Under-Secretary General : Egemen Büyükkaya Academic Assıstant : Ümit Altar Binici Table of Contents I) Introduction to the Committee: Historical Security Council……………………………...3 II) Introduction to the Agenda Item: Khmer Rouge’s Cambodia……………………………6 A. Historical Background…………………………………………………………………...9 1) French Colonialism and the Early Communist Movements in Cambodia………….....9 2) Independence of Cambodia and the Rule of Norodom Sihanouk……………………12 3) Cold War Period and 1970 Coup……………………………………………………..14 4) The Establishment and Destruction Lon Nol Government…………………………..15 B. Khmer Rouge Ideology…………………………………………………………………16 C. Internal Formation of the Communist Party of Kampuchea………………………..20 D. Foreign Relations of Democratic Kampuchea………………………………………...21 III) Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………...22 Letter from the Secretary-General Dear Delegates and Advisors, It is a great pleasure and honor to officially invite all of you to HASMUN 2019 which will be held between 26th and 28th of April 2019 at Kadir Has University Haliç Campus in Istanbul which is located in the Golden Horn area. I am personally thrilled to take part in the making of this conference and I am sure that the academic and organisation teams share my passion about this installment of HASMUN in which we have chosen to focus on topics that bring humanity together. And we have also included committees which will simulate historical events that can be considered existential threats which brought the international committee or some nations together. The general idea that we would like to introduce is that humanity can achieve great things in little time if we are united, or can eliminate threats that threaten our very existence. -

A History of the Anlong Veng Community a History Of

A HIstoRy Of Anlong Veng CommunIty A wedding in Anlong Veng in the early 1990s. (Cover photo) Aer Vietnamese forces entered Cambodia in 1979, many Khmer Rouge forces scaered to the jungles, mountains, and border areas. Mountain 1003 was a prominent Khmer Rouge military base located within the Dangrek Mountains along the Cambodian-Thai border, not far from Anlong Veng. From this military base, the Khmer Rouge re-organized and prepared for the long struggle against Vietnamese and the People’s Republic of Kampuchea government forces. Eventually, it was from this base, Khmer Rouge forces would re-conquer and sele Anlong Veng in early 1990 (and a number of other locations) until their re-integration into Cambodian society in late 1998. In many ways, life in Anlong Veng was as difficult and dangerous as it was in Mountain 1003. As one of the KR strongholds, Anlong Veng served as one of the key launching points for Khmer Rouge guerrilla operations in Cambodia, and it was subject to constant aacks by Cambodian government forces. Despite the perilous circumstances and harsh environment, the people who lived in Anlong Veng endeavored, whenever possible, to re-connect with and maintain their rich cultural heritage. Tossed from the seat of power in 1979, the Khmer Rouge were unable to sustain their rigid ideo- logical policies, particularly as it related to community and family life. During the Democratic Movement of the Khmer Rouge Final Stronghold Kampuchea regime, 1975–79, the Khmer Rouge prohibited the traditional Cambodian wedding ceremony. Weddings were arranged by Khmer Rouge leaders and cadre, who oen required mass ceremonies, with lile regard for tradition or individual distinction. -

In the Shadows: Women, Power and Politics in Cambodia

In the Shadows: Women, Power and Politics in Cambodia Kate Frieson CAPI Associate and United N ations Regional Spokesperson, UNMIBH (UN mission in Bosnia Hercegovina) Occasional Paper No. 26 June 2001 Copyright © 2001 Centre for Asia-Pacific Initiatives Box 1700, STN CSC Victoria, BC Canada V8W 2Y2 Tel. : (250) 721-7020 Fax : (250) 721-3107 E-mail: [email protected] National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data Frieson, Kate G. (Kate Grace), 1958- In the Shadows: Women, Power and Politics in Cambodia (CAPI occasional paper series ; 26) ISBN 1-55058-230-5 1. Cambodia–Social conditions. 2. Cambodia–Politics and government. 3. Women in politics–Cambodia. I. UVic Centre for Asia-Pacific Initiatives. II. Title. III. Series: Occasional papers (UVic Centre for Asia-Pacific Initiatives) ; #26. DS554.8.F74 2001 305.42'09596 C2001-910945-8 Printed in Canada Table of Contents Theoretical Approaches to Gender and Politics ......................................1 Women and the Politics of Socialization ............................................2 Women and the State: Regeneration and the Reproduction of the Nation ..................4 Women and the Defense of the State during War-Time ................................8 Women as Defenders of the Nation ...............................................12 Women in Post-UNTAC Cambodia ..............................................14 Conclusion ..................................................................16 Notes ......................................................................16 In the Shadows: Women, Power and Politics in Cambodia Kate Frieson, University of Victoria "Behind almost all politicians there are women in the shadows" Anonymous writer, Modern Khmer News, 1954 Although largely unscribed in historical writings, women have played important roles in the Cambodian body politic as lance-carrying warriors and defenders of the Angkorean kingdom, influential consorts of kings, deviant divas, revolutionary heroines, spiritual protectors of Buddhist temples, and agents of peace. -

To Keep You Is No Gain, to Kill You Is No Loss* – Securing Justice Through the International Criminal Court

TO KEEP YOU IS NO GAIN, TO KILL YOU IS NO LOSS* – SECURING JUSTICE THROUGH THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT Talitha Gray** I. INTRODUCTION “We who have witnessed in the twentieth century, the worst crimes against humanity, have an opportunity to bequeath to the new century a powerful instrument of justice. So let us rise to this challenge.”1 An incomprehensible number of people have died as a result of war crimes, genocide, and crimes against humanity in the last century. After World War II and the Holocaust, nations and their citizenry proclaimed that never again would something so horrendous happen. “We must make sure that their deaths have posthumous meaning. We must make sure that from now until the end of days all humankind stares this evil in the face . and only then can we be sure it will never arise again.”2 Despite this vow, from 1950 to 1990, there were seventeen genocides, with two that resulted in the death of over a million people.3 In 1994, 800,000 Tutsis died during a three-month genocide in Rwanda.4 Genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity are not only something that occurred in the distant past; sadly, they remain a vivid reality. If there is ever hope to end such crimes, they must be addressed by the law on an international scale. “We stand poised at the edge of invention: a rare occasion to build a new institution to serve a global need. An International Criminal Court is within our * This phrase is identified as the motto of the Khmer Rouge regime who murdered in excess of two million Cambodians during their three year reign. -

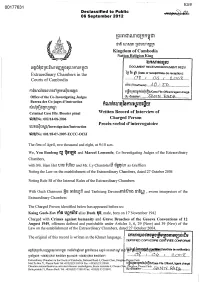

Iq~T5~E!Eiu11ttime5.?T$~~$6 CERTIFIED COPY/COPIE CERTIFIEE Conf:ORME

E3/5 00177631 Declassified to Public 06 September 2012 tbl~f1l!mmt1tfifi1fth, mei hlIfiJln tbl~tHmnJtn Kingdom of Cambodia Nation Religion King ~~iesru 11 a~~~t1ttf~lMtf~n!~tjMffuli~m DOCUMENT RECElVEDIDOCUMENT RECU I I Extraordinary Chambers in the 111 is !p (Date of receipt/Date de reception); Courts of Cambodia .......... O.K·· ..I· ...... Q4 .... J ...... 2..0.0.~ ...... tihu (T!melHeure): .••.• ,A.O'.,':. ..s.12 ......................... til 1ttrmJruhltJltmLnm~t1m~n t!'rjg~ruu~i'lr3r~ln~/Case File Offlcer/L'agent charge Office of the Co-Investigating Judges du dossier; ....... SAN:N ... .t:~>&I).~ .............. Bureau des Co-juges d'instruction o • 'II ... nMn1tnq1Bff'lf~nnvm firru)tU ~ Lm!l ~ q{l Criminal Case File !Dossier penal Written Record of Interview of trnf3/No: 002/14-08-2006 Charged Person Proces-verbal d'interrogatoire tnnm-trt1ClJ~/Investigation/Instruction trnf3/No: 001118-07 -2007-ECCC-OCIJ The first of April, two thousand and eight, at 9: 10 a.m. We, You Bunleng til ~B1'U~ and Marcel Lemonde, Co-Investigating Judges of the Extraordinary Chambers, c.J _ IS ~ with Mr. Ham Hel tntf ttnrn and Mr. Ly Chantola rn cr§~M as Greffiers Noting the Law on the establishment of the Extraordinary Chambers, dated 27 October 2004 Noting Rule 58 of the Internal Rules of the Extraordinary Chambers With Ouch Channora iicr m~ruul and Tanheang Davannm~fin~ mfM , sworn interpreters of the ~ ~ ~ Extraordinary Chambers The Charged Person identified below has appeared before us: Kaing Guek-Eav m~ ngniil1 alias Duch qt!, male, born on 17 November 1942 Charged with Crimes against humanity and Grave Breaches of the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, offences defined and punishable under Articles 5, 6, 29 (New) and 39 (New) of the Law on the establishment of the Extraordinary Chambers, dated 27 October 2004. -

The Khmer Rouge Tribunal: an Ambiguous Good News Story

perspectives The Khmer Rouge Tribunal: An Ambiguous Good News Story Milton Osborne A u g u s t 2 0 0 7 The Lowy Institute for International Policy is an independent international policy think tank based in Sydney, Australia. Its mandate ranges across all the dimensions of international policy debate in Australia – economic, political and strategic – and it is not limited to a particular geographic region. Its two core tasks are to: • produce distinctive research and fresh policy options for Australia’s international policy and to contribute to the wider international debate. • promote discussion of Australia’s role in the world by providing an accessible and high quality forum for discussion of Australian international relations through debates, seminars, lectures, dialogues and conferences. Lowy Institute Perspectives are occasional papers and speeches on international events and policy. The views expressed in this paper are the author’s own and not those of the Lowy Institute for International Policy. The Khmer Rouge Tribunal: an ambiguous good news story Milton Osborne It’s [the Khmer Rouge Tribunal] heavily symbolic and won’t have much to do with justice . It will produce verdicts which delineate the KR leadership as having been a small group and nothing to do with the present regime. Philip Short, author of Pol Pot: anatomy of a nightmare, London, 2004, quoted in Phnom Penh Post, 26 January8 February 2007. Some ten months after it was finally inaugurated in July 2006, and more than twentyeight years after the overthrow of the Democratic Kampuchean (DK) regime led by Pol Pot, the Extraordinary Chambers of the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), more familiarly known as the Khmer Rouge Tribunal, has at last handed down its first indictment. -

Perspectives

perspectives The Khmer Rouge Tribunal: An Ambiguous Good News Story Milton Osborne A u g u s t 2 0 0 7 The Lowy Institute for International Policy is an independent international policy think tank based in Sydney, Australia. Its mandate ranges across all the dimensions of international policy debate in Australia – economic, political and strategic – and it is not limited to a particular geographic region. Its two core tasks are to: • produce distinctive research and fresh policy options for Australia’s international policy and to contribute to the wider international debate. • promote discussion of Australia’s role in the world by providing an accessible and high quality forum for discussion of Australian international relations through debates, seminars, lectures, dialogues and conferences. Lowy Institute Perspectives are occasional papers and speeches on international events and policy. The views expressed in this paper are the author’s own and not those of the Lowy Institute for International Policy. The Khmer Rouge Tribunal: an ambiguous good news story Milton Osborne It’s [the Khmer Rouge Tribunal] heavily symbolic and won’t have much to do with justice . It will produce verdicts which delineate the KR leadership as having been a small group and nothing to do with the present regime. Philip Short, author of Pol Pot: anatomy of a nightmare, London, 2004, quoted in Phnom Penh Post, 26 January8 February 2007. Some ten months after it was finally inaugurated in July 2006, and more than twentyeight years after the overthrow of the Democratic Kampuchean (DK) regime led by Pol Pot, the Extraordinary Chambers of the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), more familiarly known as the Khmer Rouge Tribunal, has at last handed down its first indictment. -

KRT TRIAL MONITOR Case 002 ! Issue No

KRT TRIAL MONITOR Case 002 ! Issue No. 32 ! Hearing on Evidence Week 27 ! 13-16 August 2012 Case of Nuon Chea, Khieu Samphan and Ieng Sary Asian International Justice Initiative (AIJI), a project of East-West Center and UC Berkeley War Crimes Studies Center …Let me apologize to the Cambodians who lost their children or parents. What I am saying here is the truth. And I personally lost some of my relatives, aunts and uncles. And for those brothers in their capacity as leaders, they also lost relatives and family members. - Witness Suong Sikoeun I. OVERVIEW* After the suspension of Monday’s hearing caused by Ieng Sary’s poor health, trial resumed on Tuesday with the conclusion of the testimony of Mr. Ong Thong Hoeung, an intellectual who returned to Cambodia during DK and found himself performing manual labor in re- education camps to “refashion” himself. Next, the Chamber called Mr. Suong Sikoeun, the director of information and propaganda of the Minister of Foreign Affairs (MFA), to resume his testimony. Suong Sikoeun expounded on the MFA, FUNK and GRUNK, and Pol Pot’s role in DK. Giving due consideration to his frail health, the Trial Chamber limited his examination to half-day sessions. To manage the time efficiently, reserve witness Ms. Sa Siek (TCW-609), a cadre who worked at the Ministry of Propaganda during the regime, commenced her testimony. Sa Siek focused on the evacuation of Phnom Penh, the structure of the Ministry of Propaganda, and DK radio broadcasts. Procedural issues arose during the hearing on Wednesday, when the Trial Chamber issued unclear rulings on the introduction of documents to witnesses. -

ECCC, Case 002/01, Issue 52

KRT TRIAL MONITOR Case 002 ■ Issue No. 52 ■ Hearing on Evidence Week 47 ■ 5 and 7 February2013 Case of Nuon Chea, Khieu Samphan and Ieng Sary Asian International Justice Initiative (AIJI), a project of East-West Center and UC Berkeley War Crimes Studies Center * And if you, the Accused, are willing to conduct your self-criticism, you would clearly see the undeniable result through invaluable and countless evidence… And that is the mass crimes committed by the revolutionary Angkar.1 - Civil Party Pin Yathay I. OVERVIEW This week the Court held only two days of hearing due to the health status of Nuon Chea. The Chamber announced that the Accused, who had been released from Khmer-Soviet Friendship Hospital the previous Thursday, had to be readmitted the following Saturday. Therefore, this week’s proceedings only addressed issues that did not pertain to his case, or certain specific topics for which he had waived his right to attend, namely the continuation of document presentation on Khieu Samphan’s role in the DK regime2 and the hearing of Civil Party Pin Yathay’s testimony. The documents presented on Tuesday shed further light on the ideological leaning of Khieu Samphan, his involvement in CPK’s Standing Committee, and the degree of his role in and knowledge of the disastrous agricultural policies of the regime, the purging, and the massacres. On Thursday, Pin Yathay took the stand and testified on his experience throughout the first and second wave of evacuation during the Democratic Kampuchea period before he absconded to Thailand in 1977. II. SUMMARY OF CIVIL PARTY TESTIMONY Pin Yathay was born in 9 March 1944. -

![ANNEX 4: KHIEU SAMPHAN CHRONOLOGY [With Evidentiary Sources]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3426/annex-4-khieu-samphan-chronology-with-evidentiary-sources-2043426.webp)

ANNEX 4: KHIEU SAMPHAN CHRONOLOGY [With Evidentiary Sources]

00948464 E295/6/1.4 ANNEX 4: KHIEU SAMPHAN CHRONOLOGY [With Evidentiary Sources] Date Fact Source 27 July 1931 Khieu Samphan was born at Commune of Rom (1) E3/557, Khieu Samphan OCIJ Statement, 19 November 2007, at ENG 00153266, KHM 00153228, FRE 00153296; Chek, District of Rom Duol, Srok Rumduol, Svay (2) E1!21.1, Transcript, 13 December 2012, Khieu Samphan, 13.58.25; Rieng Province to his parents Khieu Long and Ly (3) E3/110, Sasha Sher, The Biography 0/ Khieu Samphan, at ENG 00280537, KHM Kong. 00702682, FRE 00087511; (4) E3/27, Khieu Samphan OCIJ Statement, 13 December 2007, at ENG 00156741. 1944 -1947 Khieu Samphan attended Preah Sihanouk College (1) E3/9, Philip Short, Pol Pot: The History 0/ a Nightmare, at ENG 00396223-26, FRE 00639487-91; in Kampong Cham one year behind Saloth Sar. (2) E3/713, Khieu Samphan Interview, January 2004, at ENG 00177979, KHM Khieu Samphan and Saloth Sar alias Pol Pot 00792436-37, FRE 00812131; organized for a theatre troupe to tour the provinces to (3) El!189.1, Transcript, 6 May 2013, Philip Short 09.24.24 to 09.26.54; (4) E1!21.1, Transcript, 13 December 2012, Khieu Samphan,14.03.34 to 14.05.20; raise money for them to visit the temples of Angkor (5) E3/2357R, Video Entitled "Pol Pot: The Journey to the Killing Fields," 2005, 06:04 to Wat. 06: II. 1946 Khieu Samphan, since 1946, had been actively E3/111, Ieng Sary Interview, 31 January 1972, at ENG 00762419, KHM 00711435-36, FRE 00738627. -

The Life Course of Pol Pot: How His Early Life Influenced the Crimes He Committed

Scientific THE LIFE COURSE OF POL POT: HOW HIS EARLY LIFE INFLUENCED THE CRIMES HE COMMITTED Myra de Vries1* Maartje Weerdesteijn** ABSTRACT International criminology focuses mostly on the lower level perpetrators even though it finds the leader is crucial for orchestrating the circumstances in which these people kill. While numerous theories from ordinary criminology have been usefully applied to these lower level perpetrators, the applicability of these theories to the leaders has remained underexplored. In order to fill this gap, the life course theory of Sampson and Laub will be applied to Pol Pot whose brutal communist regime cost the lives of approximately 1.7 million people. A unusual childhood, the influence of peers while he studied in Paris, and his marriage to a woman who shared his revolutionary mind-set, were all negative turning-points for Pol Pot. I. Introduction Mass violence is constructed as something extraordinary that violates cosmopolitan, and perhaps even universal, norms.2 The extraordinary nature of these crimes lies in the fact that these are very often a state-directed effort to harm or kill marginalised groups. These crimes are also referred to as “crimes of obedience,”3 since lower level perpetrators often obey high level orders unquestioningly without taking personal responsibility for the ethical repercussions.4 *Myra de Vries graduated her BSc Criminologie at Leiden University in 2012, and is currently a student in the MSc International Crimes and Criminology programme. **Maartje Weerdesteijn is an assistant professor at the department of criminology at VU University Amsterdam and researcher at the Center for International Criminal Justice. -

Proquest Dissertations

RICE UNIVERSITY Tracing the Last Breath: Movements in Anlong Veng &dss?e?73&£i& frjjrarijsfass cassis^ scesse & w o O as by Timothy Dylan Wood A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE Doctor of Philosophy APPROVED, THESIS COMMITTEE: y' 7* Stephen A. Tyler, Herbert S. Autrey Professor Department of Philip R. Wood, Professor Department of French Studies HOUSTON, TEXAS MAY 2009 UMI Number: 3362431 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI UMI Microform 3362431 Copyright 2009 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ABSTRACT Tracing the Last Breath: Movements in Anlong Veng by Timothy Dylan Wood Anlong Veng was the last stronghold of the Khmer Rouge until the organization's ultimate collapse and defeat in 1999. This dissertation argues that recent moves by the Cambodian government to transform this site into an "historical-tourist area" is overwhelmingly dominated by commercial priorities. However, the tourism project simultaneously effects an historical narrative that inherits but transforms the government's historiographic endeavors that immediately followed Democratic Kampuchea's 1979 ousting.