Rethinking Transitional Justice: Cambodia, Genocide, and a Victim-Centered Model Isabelle Chan Macalester College, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNSC Play Their Part

HASMUN’19 STUDY GUIDE The United Nations Security Council Khmer Rouge’s Cambodia Under-Secretary General : Egemen Büyükkaya Academic Assıstant : Ümit Altar Binici Table of Contents I) Introduction to the Committee: Historical Security Council……………………………...3 II) Introduction to the Agenda Item: Khmer Rouge’s Cambodia……………………………6 A. Historical Background…………………………………………………………………...9 1) French Colonialism and the Early Communist Movements in Cambodia………….....9 2) Independence of Cambodia and the Rule of Norodom Sihanouk……………………12 3) Cold War Period and 1970 Coup……………………………………………………..14 4) The Establishment and Destruction Lon Nol Government…………………………..15 B. Khmer Rouge Ideology…………………………………………………………………16 C. Internal Formation of the Communist Party of Kampuchea………………………..20 D. Foreign Relations of Democratic Kampuchea………………………………………...21 III) Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………...22 Letter from the Secretary-General Dear Delegates and Advisors, It is a great pleasure and honor to officially invite all of you to HASMUN 2019 which will be held between 26th and 28th of April 2019 at Kadir Has University Haliç Campus in Istanbul which is located in the Golden Horn area. I am personally thrilled to take part in the making of this conference and I am sure that the academic and organisation teams share my passion about this installment of HASMUN in which we have chosen to focus on topics that bring humanity together. And we have also included committees which will simulate historical events that can be considered existential threats which brought the international committee or some nations together. The general idea that we would like to introduce is that humanity can achieve great things in little time if we are united, or can eliminate threats that threaten our very existence. -

Minor Characters

August 28, 2005 New York Times Minor Characters By ELIZABETH BECKER The Tuol Sleng Museum, housed in the former KhmerRouge secret prison in Phnom Penh, is Cambodia's memorial to the nearly twomillion people who died during the genocidal reign of Pol Pot. Among all those victims, one woman's life -- and death-- has come to symbolize the horrors of the Khmer Rouge regime. Her name isHout Bophana, and her story is told in a movie shown twice a day at the museum.Sometimes called the Anne Frank of Cambodia, Bophana has become a folk heroine,known for the letters and confessions she wrote before her torture and murderby the Khmer Rouge. Every novelist knows that minor characters have a wayof taking over the narrative. But in the years since I first told her story inmy 1986 book, ''When the War Was Over,'' a history of modern Cambodia, Bophanahas taken on a life of her own and shown me the same thing can happen innonfiction. Then again, Bophana was overwhelming from the start. In the immediate years after the Vietnamese overthrewPol Pot, researchers got a first look at the hundreds of secret files kept atTuol Sleng. Our priority was to reconstruct the history of Pol Pot's regime,which forced confessions of key political figures. But I also searched foraverage Cambodians, people whose individual stories could illuminate the largertragedy. When I unearthed Bophana's file in 1981, my stomach dropped. Thedossier was filled with love letters. In the middle of one of the 20thcentury's worst instances of mass murder, here was a beautiful young womansecretly writing love letters to her husband, knowing full well that in theclosed Khmer dictatorship, she would be killed if they were found. -

Iq~T5~E!Eiu11ttime5.?T$~~$6 CERTIFIED COPY/COPIE CERTIFIEE Conf:ORME

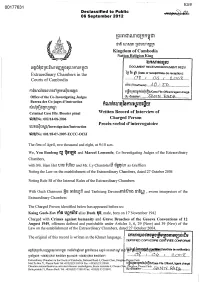

E3/5 00177631 Declassified to Public 06 September 2012 tbl~f1l!mmt1tfifi1fth, mei hlIfiJln tbl~tHmnJtn Kingdom of Cambodia Nation Religion King ~~iesru 11 a~~~t1ttf~lMtf~n!~tjMffuli~m DOCUMENT RECElVEDIDOCUMENT RECU I I Extraordinary Chambers in the 111 is !p (Date of receipt/Date de reception); Courts of Cambodia .......... O.K·· ..I· ...... Q4 .... J ...... 2..0.0.~ ...... tihu (T!melHeure): .••.• ,A.O'.,':. ..s.12 ......................... til 1ttrmJruhltJltmLnm~t1m~n t!'rjg~ruu~i'lr3r~ln~/Case File Offlcer/L'agent charge Office of the Co-Investigating Judges du dossier; ....... SAN:N ... .t:~>&I).~ .............. Bureau des Co-juges d'instruction o • 'II ... nMn1tnq1Bff'lf~nnvm firru)tU ~ Lm!l ~ q{l Criminal Case File !Dossier penal Written Record of Interview of trnf3/No: 002/14-08-2006 Charged Person Proces-verbal d'interrogatoire tnnm-trt1ClJ~/Investigation/Instruction trnf3/No: 001118-07 -2007-ECCC-OCIJ The first of April, two thousand and eight, at 9: 10 a.m. We, You Bunleng til ~B1'U~ and Marcel Lemonde, Co-Investigating Judges of the Extraordinary Chambers, c.J _ IS ~ with Mr. Ham Hel tntf ttnrn and Mr. Ly Chantola rn cr§~M as Greffiers Noting the Law on the establishment of the Extraordinary Chambers, dated 27 October 2004 Noting Rule 58 of the Internal Rules of the Extraordinary Chambers With Ouch Channora iicr m~ruul and Tanheang Davannm~fin~ mfM , sworn interpreters of the ~ ~ ~ Extraordinary Chambers The Charged Person identified below has appeared before us: Kaing Guek-Eav m~ ngniil1 alias Duch qt!, male, born on 17 November 1942 Charged with Crimes against humanity and Grave Breaches of the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, offences defined and punishable under Articles 5, 6, 29 (New) and 39 (New) of the Law on the establishment of the Extraordinary Chambers, dated 27 October 2004. -

Vietnam Detained Khmer-Krom Youth for Distributing the UN DRIP

KKF’s Report April 16, 2021 Vietnam Detained Khmer-Krom Youth for Distributing the UN DRIP On Thursday, September 13, 2007, the General Assembly voted to adopt the United Nations Declarations on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UN DRIP). As a member state, Vietnam signed to adopt this crucial and historical document. Since signing to the adoption of the UN DRIP, Vietnam has continued to deny the existence of the indigenous peoples within its border. Vietnam has labeled the indigenous peoples as the “ethnic minority.” The Khmer-Krom people, the indigenous peoples of the Mekong Delta, have been living on their ancestral lands for thousands of years before the Vietnamese people came to live in the region. Lacking recognition as the indigenous peoples, the Khmer-Krom people have not enjoyed the fundamental rights enshrined in the UN DRIP. Instead of trying to protect and promote the fundamental rights of the indigenous peoples, Vietnam has tried to use all the tactics to make the indigenous peoples invisible in their homeland by not recognizing their true identity. The Khmer-Krom people are not allowed to identify themselves as Khmer-Krom, but being labeled as “Khmer Nam Bo.” Moreover, even Vietnam signed to adopt UN DRIP, but Vietnam has not translated the UN DRIP to the indigenous language and distributed the UN DRIP freely to indigenous peoples. Vietnam is a one-party communist state. Vietnam does not allow freedom of association. As a non- profit organization based in the United States to advocate for the fundamental rights of the voiceless Khmer-Krom in the Mekong Delta, the Khmers Kampuchea-Krom Federation (KKF) has not allowed operating in Vietnam. -

Full Issue 8.2

Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal Volume 8 Issue 2 Post-Genocide Cambodia: The Politics Article 2 of Justice and Truth Recovery 5-1-2014 Full Issue 8.2 Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp Recommended Citation (2014) "Full Issue 8.2," Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal: Vol. 8: Iss. 2: Article 2. Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp/vol8/iss2/2 This Front Matter is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ISSN 1911-9933 eISSN 1911-9933 Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal Post-Genocide Cambodia: The Politics of Justice and Truth Recovery Volume 8.2 - 2014 ii ©2014 Genocide Studies and Prevention 8, no. 2 iii Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp/ Volume 8.2 - 2014 Post-Genocide Cambodia: The Politics of Justice and Truth Recovery GSP Interim Editorial Board Editorial ...............................................................................................................................................1 Kosal Path and Elena Lesley-Rozen Introduction ......................................................................................................................................3 Articles Alex Hinton Justice and Time -

New Beginnings

New Beginnings Refugee Stories - Nelson A Snapshot of Success NEW BEGINNINGS Refugee Stories - Nelson First Published 2012 Nelson Multicultural Council 4 Bridge Street, Nelson PO Box 264, Nelson 7040 ISBN: 978-0-473-21735-8 Copy writing by Alison Gibbs Copy edited by Claire Nichols, Bob Irvine Designed and typeset by Revell Design - www.revelldesign.co.nz Printed by Speedyprint - www.speedyprint.co.nz Contents INTRODUCTION ...................................................................1 Van Ro Hlawnceu Mal Sawm Cinzah REFUGEE RESETTLEMENT IN NEW ZEALAND ..........2 Van Hlei Sung Lian ............................................................ 11 REFUGEE COMMUNITIES IN NELSON ..........................3 THE ETHNIC COMMUNITIES IN NELSON ................. 12 REFUGEE PROFILES ............................................................4 Burma .................................................................................... 12 Beda and Chandra Dahal .................................................4 Burmese ................................................................................ 12 Trang Lam ...............................................................................5 Chin ........................................................................................ 12 Theresa Zam Deih Cin .........................................................5 Zomi Innkuan ...................................................................... 13 Govinda (Tika) Regmi..........................................................6 Kayan .................................................................................... -

Oppenheim � � � a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of The

When States! Fall Apart by! Benjamin Aaron! Oppenheim ! ! ! A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate! Division of the University of California,! Berkeley ! ! ! Committee in charge: Professor Steven Weber, Chair Professor Ron Hassner Professor Edwin Epstein Professor George Rutherford Spring! 2014 ! Abstract When States Fall Apart by Benjamin Aaron Oppenheim Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley ! Professor Steven Weber, Chair Failed states—countries in which governing institutions have corroded or collapsed— are considered by many scholars to pose a grave threat to global security. Policymakers broadly share this view. The United States’ 2002 National Security Strategy flatly declared that “America is now threatened less by conquering states than by failing ones”, while the United Nations warns of the !global dangers posed by states that cannot meet their responsibilities as sovereign powers. The conventional wisdom on the risks posed by failed states represents a significant shift in international relations scholarship, which has traditionally emphasized the threat that strong states pose to weaker polities. It also represents a shift in foreign policy, as fears of state failure have flooded resources into shoring up weak states and reconstructing failed ones. But do failed states pose a global security threat? Despite the stakes, there has been little empirical research that isolates and tests the causal mechanisms linking state failure with specific threats. This project empirically assesses the consequences of state failure, through an investigation of several security threats of global significance: transnational terrorism, and pandemic disease outbreaks. -

Exploring Cambodian Voices Acknowledgement

Exploring Cambodian Voices Acknowledgement This Context Analysis for the Voice represents the voices of many diverse groups and people. We would like to acknowledge all the people who provided input, guidance, and comments. Without your guidance the final product would not have turned out as strong. Thank you to civil society organisations that provided input on their work, and helped us to link with people in the community to learn of their experiences. This included HelpAge, Men’s Health Cambodia, Cambodia Association for Aid to Children, ADD International, ADHOC, LICHADO, Cambodia Center for Human Rights, Woman Organization For Modern Economy and Nursing, the TransGender Network, Cambodia Disabled People’s Organisation, CamAsean, and Cambodia Women for Peace and Development. Thank you to the various ministries that provided input on current policies, priorities and actions, including the Ministry of Women’s Affairs, Ministry of Social Affairs, Veterans and Youth Rehabilitation: Cambodia National Council for Children and the Disability Action Council. Thank you to UN Agencies that provided input on their work including the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, UN Women and UNICEF. But most importantly, thank you to all the representatives of marginalised and discriminated groups who were open and willing to share their experiences with the team. This input was invaluable for the context analysis we sincerely hope that you are as proud of the final product as we are. The representatives came from all groups within Voice including older people, indigenous people, people with disabilities, people in the LGBTQI community, women working in hospitality and tourism, and women that have experience violence and/or abuse. -

Trends in Southeast Asia

ISSN 0219-3213 2017 no. 16 Trends in Southeast Asia THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF CHINESE INVESTMENT IN CAMBODIA VANNARITH CHHEANG TRS16/17s ISBN 978-981-4786-79-9 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg 9 7 8 9 8 1 4 7 8 6 7 9 9 Trends in Southeast Asia 17-J02872 01 Trends_2017-16.indd 1 24/10/17 11:54 AM The ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute (formerly Institute of Southeast Asian Studies) is an autonomous organization established in 1968. It is a regional centre dedicated to the study of socio-political, security, and economic trends and developments in Southeast Asia and its wider geostrategic and economic environment. The Institute’s research programmes are grouped under Regional Economic Studies (RES), Regional Strategic and Political Studies (RSPS), and Regional Social and Cultural Studies (RSCS). The Institute is also home to the ASEAN Studies Centre (ASC), the Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre (NSC) and the Singapore APEC Study Centre. ISEAS Publishing, an established academic press, has issued more than 2,000 books and journals. It is the largest scholarly publisher of research about Southeast Asia from within the region. ISEAS Publishing works with many other academic and trade publishers and distributors to disseminate important research and analyses from and about Southeast Asia to the rest of the world. 17-J02872 01 Trends_2017-16.indd 2 24/10/17 11:54 AM 2017 no. 16 Trends in Southeast Asia THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF CHINESE INVESTMENT IN CAMBODIA VANNARITH CHHEANG 17-J02872 01 Trends_2017-16.indd 3 24/10/17 11:54 AM Published by: ISEAS Publishing 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 [email protected] http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg © 2017 ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore All rights reserved. -

Submission on Self-Determination Under the UN Declaration on The

Submission on Self-Determination under the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples to the Expert Mechanism on the rights of indigenous peoples Table of Contents 1 Overview............................................................................................................................................3 1.1 Summary....................................................................................................................................3 1.2 The submitting organization......................................................................................................4 2 Self determination themes................................................................................................................4 2.1 Peace and Self-Determination...................................................................................................4 2.2 Compromised spaces.................................................................................................................7 2.3 Disenfranchisement of unrepresented peoples........................................................................8 2.4 Criminalization of self-determination movements..................................................................11 2.5 International trade and self-determination.............................................................................12 2.6 Indigenous land: commerce and climate.................................................................................13 3 Conclusion.......................................................................................................................................15 -

Culture & History Story of Cambodia

CHAM CULTURE & HISTORY STORY OF CAMBODIA FARINA SO, VANNARA ORN - DOCUMENTATION CENTER OF CAMBODIA R KILLEAN, R HICKEY, L MOFFETT, D VIEJO-ROSE CHAM CULTURE & HISTORY STORYﺷﻤﺲ ISBN-13: 978-99950-60-28-2 OF CAMBODIA R Killean, R Hickey, L Moffett, D Viejo-Rose Farina So, Vannara Orn - 1 - Documentation Center of Cambodia ζរចងាំ និង យុត្ិធម៌ Memory & Justice មជ䮈មណ䮌លឯក羶រកម្宻ᾶ DOCUMENTATION CENTER OF CAMBODIA (DC-CAM) Villa No. 66, Preah Sihanouk Boulevard Phnom Penh, 12000 Cambodia Tel.: + 855 (23) 211-875 Fax.: + 855 (23) 210-358 E-mail: [email protected] CHAM CULTURE AND HISTORY STORY R Killean, R Hickey, L Moffett, D Viejo-Rose Farina So, Vannara Orn 1. Cambodia—Law—Human Rights 2. Cambodia—Politics and Government 3. Cambodia—History Funding for this project was provided by the UK Arts & Humanities Research Council: ‘Restoring Cultural Property and Communities After Conflict’ (project reference AH/P007929/1). DC-Cam receives generous support from the US Agency for International Development (USAID). The views expressed in this book are the points of view of the authors only. Include here a copyright statement about the photos used in the booklet. The ones sent by Belfast were from Creative Commons, or were from the authors, except where indicated. Copyright © 2018 by R Killean, R Hickey, L Moffett, D Viejo-Rose & the Documentation Center of Cambodia. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. -

Case Study UNICEF Cambodia Integrating Faith for Social And

Case Study UNICEF Cambodia Integrating Faith for Social and Behaviour Change into Pagoda Structures for a Systems Approach to Capacity Development Designed by: Donna Rajeh Cover photo credit: © UNICEF/UN0323043/Seng: Cambodia, 2019. A smiling student during a school break at Samdech Ov Samdech Mae Primary School in Prek Village, Sangkat Steung Treng, Steung Treng City, Steung Treng Province. 1 CONTENTS Overview 2 Background 3 What is the central intersection of child wellbeing and religion that requires a C4D approach? 4 C4D Outcomes 5 Individual/family level 5 Interpersonal/community level 5 Institutional/FBO level 5 Policy/system level 5 C4D Strategies and Approaches 6 Target groups 6 Partnerships 6 Strategies and Activities 7 Progress and Results 10 Challenges 11 Conclusions and Lessons Learned 12 Lessons learned 12 Strategies for the future include 13 Acknowledgements 13 2 UNICEF CAMBODIA – CASE STUDY OVERVIEW UNICEF Cambodia and the Ministry of Cults and Religion (MoCR) have a strong level of collaboration, which allows for widespread engagement with the Buddhist education system and pagodas across the country. Pagodas across the country represent places of safety for many children, but there is also evidence that violence can occur in these religious institutions, hence the need for a nuanced understanding of child protection in pagodas. As an outcome of collaboration with the General Inspectorate of National Buddhist Education, which is part of the Ministry, it is now compulsory for monks to learn about child protection in their training. National regulation has been adopted for Child Protection Policies to be instituted in pagodas across the country, along with training of monks in how to implement these policies.