Day of Reckoning: Pol Pot Breaks an 18-Year Silence to Confront His Past

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNSC Play Their Part

HASMUN’19 STUDY GUIDE The United Nations Security Council Khmer Rouge’s Cambodia Under-Secretary General : Egemen Büyükkaya Academic Assıstant : Ümit Altar Binici Table of Contents I) Introduction to the Committee: Historical Security Council……………………………...3 II) Introduction to the Agenda Item: Khmer Rouge’s Cambodia……………………………6 A. Historical Background…………………………………………………………………...9 1) French Colonialism and the Early Communist Movements in Cambodia………….....9 2) Independence of Cambodia and the Rule of Norodom Sihanouk……………………12 3) Cold War Period and 1970 Coup……………………………………………………..14 4) The Establishment and Destruction Lon Nol Government…………………………..15 B. Khmer Rouge Ideology…………………………………………………………………16 C. Internal Formation of the Communist Party of Kampuchea………………………..20 D. Foreign Relations of Democratic Kampuchea………………………………………...21 III) Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………...22 Letter from the Secretary-General Dear Delegates and Advisors, It is a great pleasure and honor to officially invite all of you to HASMUN 2019 which will be held between 26th and 28th of April 2019 at Kadir Has University Haliç Campus in Istanbul which is located in the Golden Horn area. I am personally thrilled to take part in the making of this conference and I am sure that the academic and organisation teams share my passion about this installment of HASMUN in which we have chosen to focus on topics that bring humanity together. And we have also included committees which will simulate historical events that can be considered existential threats which brought the international committee or some nations together. The general idea that we would like to introduce is that humanity can achieve great things in little time if we are united, or can eliminate threats that threaten our very existence. -

Revolution, Reform and Regionalism in Southeast Asia

Revolution, Reform and Regionalism in Southeast Asia Geographically, Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam are situated in the fastest growing region in the world, positioned alongside the dynamic economies of neighboring China and Thailand. Revolution, Reform and Regionalism in Southeast Asia compares the postwar political economies of these three countries in the context of their individual and collective impact on recent efforts at regional integration. Based on research carried out over three decades, Ronald Bruce St John highlights the different paths to reform taken by these countries and the effect this has had on regional plans for economic development. Through its comparative analysis of the reforms implemented by Cam- bodia, Laos and Vietnam over the last 30 years, the book draws attention to parallel themes of continuity and change. St John discusses how these countries have demonstrated related characteristics whilst at the same time making different modifications in order to exploit the strengths of their individual cultures. The book contributes to the contemporary debate over the role of democratic reform in promoting economic devel- opment and provides academics with a unique insight into the political economies of three countries at the heart of Southeast Asia. Ronald Bruce St John earned a Ph.D. in International Relations at the University of Denver before serving as a military intelligence officer in Vietnam. He is now an independent scholar and has published more than 300 books, articles and reviews with a focus on Southeast Asia, -

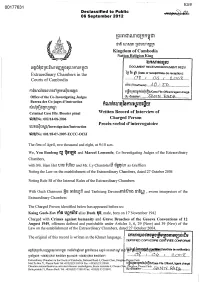

Iq~T5~E!Eiu11ttime5.?T$~~$6 CERTIFIED COPY/COPIE CERTIFIEE Conf:ORME

E3/5 00177631 Declassified to Public 06 September 2012 tbl~f1l!mmt1tfifi1fth, mei hlIfiJln tbl~tHmnJtn Kingdom of Cambodia Nation Religion King ~~iesru 11 a~~~t1ttf~lMtf~n!~tjMffuli~m DOCUMENT RECElVEDIDOCUMENT RECU I I Extraordinary Chambers in the 111 is !p (Date of receipt/Date de reception); Courts of Cambodia .......... O.K·· ..I· ...... Q4 .... J ...... 2..0.0.~ ...... tihu (T!melHeure): .••.• ,A.O'.,':. ..s.12 ......................... til 1ttrmJruhltJltmLnm~t1m~n t!'rjg~ruu~i'lr3r~ln~/Case File Offlcer/L'agent charge Office of the Co-Investigating Judges du dossier; ....... SAN:N ... .t:~>&I).~ .............. Bureau des Co-juges d'instruction o • 'II ... nMn1tnq1Bff'lf~nnvm firru)tU ~ Lm!l ~ q{l Criminal Case File !Dossier penal Written Record of Interview of trnf3/No: 002/14-08-2006 Charged Person Proces-verbal d'interrogatoire tnnm-trt1ClJ~/Investigation/Instruction trnf3/No: 001118-07 -2007-ECCC-OCIJ The first of April, two thousand and eight, at 9: 10 a.m. We, You Bunleng til ~B1'U~ and Marcel Lemonde, Co-Investigating Judges of the Extraordinary Chambers, c.J _ IS ~ with Mr. Ham Hel tntf ttnrn and Mr. Ly Chantola rn cr§~M as Greffiers Noting the Law on the establishment of the Extraordinary Chambers, dated 27 October 2004 Noting Rule 58 of the Internal Rules of the Extraordinary Chambers With Ouch Channora iicr m~ruul and Tanheang Davannm~fin~ mfM , sworn interpreters of the ~ ~ ~ Extraordinary Chambers The Charged Person identified below has appeared before us: Kaing Guek-Eav m~ ngniil1 alias Duch qt!, male, born on 17 November 1942 Charged with Crimes against humanity and Grave Breaches of the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, offences defined and punishable under Articles 5, 6, 29 (New) and 39 (New) of the Law on the establishment of the Extraordinary Chambers, dated 27 October 2004. -

First Quarterly Report: January-March, 2012

mCÄmNÐlÉkßrkm<úCa Documentation Center of Cambodia Quarterly Report: January‐March, 2012 DC‐Cam Team Leaders and the Management Team Prepared and Compiled by Farina So Office Manager Edited by Norman (Sambath) Pentelovitch April, 2012 Sirik Savina, Outreach Coordinator, discusses with the villagers about the hearing process at Khmer Rouge Tribunal. Abbreviations CHRAC Cambodian Human Rights Action Committee CP Civil Party CTM Cambodia Tribunal Monitor DC‐Cam Documentation Center of Cambodia DK Democratic Kampuchea ECCC Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia ICC International Criminal Court ITP Sida Advanced International Training Programme KID Khmer Institute for Democracy KR Khmer Rouge MMMF Margaret McNamara Memorial Fund MRDC Mondul Kiri Resource and Documentation Centre OCP Office of Co‐Prosecutors OCIJ Office of Co‐Investigating Judges PTSD Post‐Traumatic Stress Disorder Sida Swedish International Development Agency TSL Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum UN United Nations UNDP United Nation for Development Program USAID United States Agency for International Development VOT Victims of Torture VPA Victims Participation Project VSS Victim Support Section YFP Youth for Peace YRDP Youth Resource Development Program 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary.............................................................................................................. 1 Results/Outcome................................................................................................................. 7 Raised Public Awareness on the Value of Documents............................................. -

SPIONS a Lehallgatandók Nem Tudták Tovább Folytatni a Konverzációt, Nem Volt Mit Lehallgatni

Najmányi László megalapítása bejelentésének, és az aktualitását vesztett punkról az elektronikus tánczenére való áttérésnek. A frontember Knut Hamsun Éhségét olvassa, tudtam meg, aztán megszakadt a vonal. Gyakran előfordult, amikor a lehallgatók beleuntak a lehallgatásba. Ha szétkapcsolták a vonalat, SPIONS a lehallgatandók nem tudták tovább folytatni a konverzációt, nem volt mit lehallgatni. A lehall- gatók egymással dumálhattak, család, főnö- kök, csajok, bármi. Szilveszter napján biztosan Ötvenharmadik rész már délután elkezdtek piálni. Ki akar szilvesz- terkor lehallgatni? Senki. Biszku elvtárs talán. Ha éppen nem vadászik. Vagy a tévében Ernyey Béla. Amikor nyomozót játszik. � Jean-François Bizot6 (1944–2007) francia arisz- Végzetes szerelem, Khmer Rouge, Run by R.U.N. tokrata, antropológus, író és újságíró, az Actuel magazin alapító főszerkesztője7 volt az egyet- „Másképpen írok, mint ahogy beszélek. Másképpen beszélek, mint ahogy gon- len nyugati, aki túlélte a Kambodzsát 1975–79 dolkodom. Másképpen gondolkodom, mint ahogy kellene, és így mind a legmé- között terrorizáló vörös khmerek börtönét. lyebb sötétségbe hull.” A SPIONS 1978 nyarán, Robert Filliou (1926–1987) Franz Kafka francia fluxusművész közvetítésével, Párizsban ismerkedett meg vele. Többször meghívott bennünket vacsorára, és a vidéki kastélyában Az 1979-es évem végzetes szerelemmel indult. Meg ugyan nem vakított, de meg- rendezett, napokig tartó bulikra, ahol megismer- bolondított, az biztos. Művészileg pedig – bár addigra már annyira eltávolodtam kedhettünk a francia punk és new wave szcéna a művészettől, amennyire ez lehetséges – feltétlenül inspirált. Tragikus szerelem prominens művészeivel, producerekkel, mene- volt, a műfaj minden mélységével, szépségével, banalitásával és morbiditásával. dzserekkel, koncertszervezőkkel, független Kívülről nézve persze roppant mulatságos, különösen azért, mert én, a gép, a kém, lemezkiadókkal és a vezető rock-újságírókkal. -

Download.Html; Zsombor Peter, Loss of Forest in Cambodia Among Worst in the World, Cambodia Daily, Nov

CAMBODIA LAW AND POLICY JOURNAL 2013-2014 CHY TERITH Editor-in-Chief, Khmer-language ANNE HEINDEL Editor-in-Chief, English-language CHARLES JACKSON SHANNON MAREE TORRENS Editorial Advisors LIM CHEYTOATH SOKVISAL KIMSROY Articles Editors, Khmer-language LIM CHEYTOATH SOPHEAK PHEANA SAY SOLYDA PECHET MEN Translators HEATHER ANDERSON RACHEL KILLEAN Articles Editor, English-language YOUK CHHANG, Director, Documentation Center of Cambodia JOHN CIORCIARI, Assistant Professor of Public Policy, Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy, Michigan University RANDLE DEFALCO, Articling Student-at-Law at the Hamilton Crown Attorney’s Office, LL.M, University of Toronto JAYA RAMJI-NOGALES, Associate Professor, Temple University Beasley School of Law PEOUDARA VANTHAN, Deputy Director Documentation Center of Cambodia Advisory Board ISSN 2408-9540 Disclaimer: The views expressed in this journal are those of the authors only. Copyright © 2014 by the Documentation Center of Cambodia. All rights reserved. No part of this journal may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Cambodia Law and PoLiCY JoURnaL Eternal (2013). Painting by Asasax The Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam) is pleased to an- design, which will house a museum, research center, and a graduate nounce Cambodia’s first bi-annual academic journal published in English studies program. The Cambodia Law and Policy Journal, part of the and Khmer: The Cambodia Law and Policy Journal (CLPJ). DC-Cam Center’s Witnessing Justice Project, will be the Institute’s core academic strongly believes that empowering Cambodians to make informed publication. -

Killing Hope U.S

Killing Hope U.S. Military and CIA Interventions Since World War II – Part I William Blum Zed Books London Killing Hope was first published outside of North America by Zed Books Ltd, 7 Cynthia Street, London NI 9JF, UK in 2003. Second impression, 2004 Printed by Gopsons Papers Limited, Noida, India w w w.zedbooks .demon .co .uk Published in South Africa by Spearhead, a division of New Africa Books, PO Box 23408, Claremont 7735 This is a wholly revised, extended and updated edition of a book originally published under the title The CIA: A Forgotten History (Zed Books, 1986) Copyright © William Blum 2003 The right of William Blum to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Cover design by Andrew Corbett ISBN 1 84277 368 2 hb ISBN 1 84277 369 0 pb Spearhead ISBN 0 86486 560 0 pb 2 Contents PART I Introduction 6 1. China 1945 to 1960s: Was Mao Tse-tung just paranoid? 20 2. Italy 1947-1948: Free elections, Hollywood style 27 3. Greece 1947 to early 1950s: From cradle of democracy to client state 33 4. The Philippines 1940s and 1950s: America's oldest colony 38 5. Korea 1945-1953: Was it all that it appeared to be? 44 6. Albania 1949-1953: The proper English spy 54 7. Eastern Europe 1948-1956: Operation Splinter Factor 56 8. Germany 1950s: Everything from juvenile delinquency to terrorism 60 9. Iran 1953: Making it safe for the King of Kings 63 10. -

Hun Sen, the UN, and the Khmer Rouge Tribunal

UCLA UCLA Pacific Basin Law Journal Title Not Worth the Wait: Hun Sen, the UN, and the Khmer Rouge Tribunal Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4rh6566v Journal UCLA Pacific Basin Law Journal, 24(1) Author Bowman, Herbert D. Publication Date 2006 DOI 10.5070/P8241022188 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California NOT WORTH THE WAIT: HUN SEN, THE UN, AND THE KHMER ROUGE TRIBUNAL Herbert D. Bowman* I. INTRODUCTION Between 1975 and 1979, the Khmer Rouge killed between one and three million Cambodians.1 Twenty-four years later, on March 17, 2003, the United Nations and the Cambodian govern- ment reached an agreement to establish a criminal tribunal de- signed to try those most responsible for the massive human rights violations which took place during the Khmer Rouge reign of terror. 2 Another three years later, on July 4, 2006, international and Cambodian judges and prosecutors were sworn in to begin work at the Extraordinary Chamber in the Courts of Cambodia ("ECCC"). 3 To quickly grasp the Cambodia court's prospects for success, one only need know a few basic facts. First, the jurisdiction of the court will be limited to crimes 4 that took place between April 17, 1975 and January 6, 1979. * Fellow of Indiana University School of Law, Indianapolis Center for Inter- national & Comparative Law. Former International Prosecutor for the United Na- tions Mission to East Timor. The author is currently working and living in Cambodia. 1. Craig Etcheson, The Politics of Genocide Justice in Cambodia, in INTERNA- TIONALIZED CRIMINAL COURTS: SIERRA LEONE, EAST TIMOR, Kosovo AND CAM- BODIA 181-82 (Cesare P.R. -

Backgrounder No. 1255: "Rebuilding the U.S.-Philippine Alliance"

No. 1255 February 22, 1999 REBUILDING THE U.S.–PHILIPPINE ALLIANCE RICHARD D. FISHER, JR. During the Cold War, the military alliance the Spratly group to the south. It is clear that over between the United States and the Philippines, the next decade China intends to develop facilities embodied in the 1951 Mutual Defense Treaty, was in this area that could assist military operations. instrumental in deterring the spread of Soviet China already has a large airstrip on Woody Island communism in Asia. This once-strong in the Paracels that places current and future com- relationship, however, has been essentially mori- bat aircraft within striking bund since U.S. air and naval forces departed their distance of the Philippines bases in the Philippines in 1992. The lack of and Spratlys. And in the Produced by defense cooperation between old allies has created Spratlys, as seen most The Asian Studies Center a power vacuum that China has been exploiting. recently on Mischief Reef, Since 1995, for example, with little reaction from China is building larger out- Published by the Clinton Administration, China has built and posts that could support The Heritage Foundation expanded structures on Mischief Reef in the helicopters and ships. 214 Massachusetts Ave., N.E. Spratly Island chain, about 150 miles from Philip- China’s air and naval forces Washington, D.C. pine territory but over 800 miles away from the already are superior to those 20002–4999 Chinese mainland. The Clinton Administration of the Philippines, and in (202) 546-4400 http://www.heritage.org needs to tell China clearly that such actions under- the not-too-distant future mine peace in Southeast Asia. -

ECCC, Case 002/01, Issue 52

KRT TRIAL MONITOR Case 002 ■ Issue No. 52 ■ Hearing on Evidence Week 47 ■ 5 and 7 February2013 Case of Nuon Chea, Khieu Samphan and Ieng Sary Asian International Justice Initiative (AIJI), a project of East-West Center and UC Berkeley War Crimes Studies Center * And if you, the Accused, are willing to conduct your self-criticism, you would clearly see the undeniable result through invaluable and countless evidence… And that is the mass crimes committed by the revolutionary Angkar.1 - Civil Party Pin Yathay I. OVERVIEW This week the Court held only two days of hearing due to the health status of Nuon Chea. The Chamber announced that the Accused, who had been released from Khmer-Soviet Friendship Hospital the previous Thursday, had to be readmitted the following Saturday. Therefore, this week’s proceedings only addressed issues that did not pertain to his case, or certain specific topics for which he had waived his right to attend, namely the continuation of document presentation on Khieu Samphan’s role in the DK regime2 and the hearing of Civil Party Pin Yathay’s testimony. The documents presented on Tuesday shed further light on the ideological leaning of Khieu Samphan, his involvement in CPK’s Standing Committee, and the degree of his role in and knowledge of the disastrous agricultural policies of the regime, the purging, and the massacres. On Thursday, Pin Yathay took the stand and testified on his experience throughout the first and second wave of evacuation during the Democratic Kampuchea period before he absconded to Thailand in 1977. II. SUMMARY OF CIVIL PARTY TESTIMONY Pin Yathay was born in 9 March 1944. -

Racial Ideology and Implementation of the Khmer Rouge Genocide

Racial Ideology and Implementation of the Khmer Rouge Genocide Abby Coomes, Jonathan Dean, Makinsey Perkins, Jennifer Roberts, Tyler Schroeder, Emily Simpson Abstract Indochina Implementation In the 1970s Pol Pot devised a ruthless Cambodian regime Communism in Cambodia began as early as the 1940s during known as the Khmer Rouge. The Khmer Rouge adopted a strong the time of Joseph Stalin. Its presence was elevated when Pol Pot sense of nationalism and discriminated against the Vietnamese and became the prime minister and leader of the Khmer Rouge. In 1975, other racial minorities in Cambodia. This form of radical Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge implemented their new government communism led to the Cambodian genocide because the Khmer the Democratic Kampuchea. This government was meant to replace Rouge cleansed the minorities of their culture and committed mass the existing one in every way possible by any means necessary. murder amongst their people in order to establish power. Pol Pot The Khmer Rouge imposed a forced cleansing of Cambodia, both in established the Democratic Kampuchea which forced what he culture and race. This meant that the Cambodian minorities were to called the “New People” to work on the farms and in the factories. be weeded out, tortured, and murdered. This was called the Four The Khmer Rouge went as far as to convert the schools into Year Plan. prisons and destroyed all traces of books and equipment to rid The Khmer Rouge started by separating the minority groups Cambodia of their education system. This project will analyze how within the country. The Khmer Rouge wedged a division between Pol Pot’s regime created systematic racism amongst the the urban and rural populations, categorizing between the “New Cambodian minorities and developed a social hierarchy. -

The Emergence of Cambodian Women Into the Public

WOMEN WALKING SILENTLY: THE EMERGENCE OF CAMBODIAN WOMEN INTO THE PUBLIC SPHERE A thesis presented to the faculty of the Center for International Studies of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Joan M. Kraynanski June 2007 WOMEN WALKING SILENTLY: THE EMERGENCE OF CAMBODIAN WOMEN INTO THE PUBLIC SPHERE by JOAN M. KRAYNANSKI has been approved for the Center for International Studies by ________________________________________ Elizabeth Fuller Collins Associate Professor, Classics and World Religions _______________________________________ Drew McDaniel Interim Director, Center for International Studies Abstract Kraynanski, Joan M., M.A., June 2007, Southeast Asian Studies WOMEN WALKING SILENTLY: THE EMERGENCE OF CAMBODIAN WOMEN INTO THE PUBLIC SPHERE (65 pp.) Director of Thesis: Elizabeth Fuller Collins This thesis examines the changing role of Cambodian women as they become engaged in local politics and how the situation of women’s engagement in the public sphere is contributing to a change in Cambodia’s traditional gender regimes. I examine the challenges for and successes of women engaged in local politics in Cambodia through interviews and observation of four elected women commune council members. Cambodian’s political culture, beginning with the post-colonial period up until the present, has been guided by strong centralized leadership, predominantly vested in one individual. The women who entered the political system from the commune council elections of 2002 address a political philosophy of inclusiveness and cooperation. The guiding organizational philosophy of inclusiveness and cooperation is also evident in other women centered organizations that have sprung up in Cambodia since the early 1990s. My research looks at how women’s role in society began to change during the Khmer Rouge years, 1975 to 1979, and has continued to transform, for some a matter of necessity, while for others a matter of choice.