Populist and Technocratic Narratives of the EU in the Brexit Referendum Campaign

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Opposition-Craft': an Evaluative Framework for Official Opposition Parties in the United Kingdom Edward Henry Lack Submitte

‘Opposition-Craft’: An Evaluative Framework for Official Opposition Parties in the United Kingdom Edward Henry Lack Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of PhD The University of Leeds, School of Politics and International Studies May, 2020 1 Intellectual Property and Publications Statements The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. ©2020 The University of Leeds and Edward Henry Lack The right of Edward Henry Lack to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 2 Acknowledgements Page I would like to thank Dr Victoria Honeyman and Dr Timothy Heppell of the School of Politics and International Studies, The University of Leeds, for their support and guidance in the production of this work. I would also like to thank my partner, Dr Ben Ramm and my parents, David and Linden Lack, for their encouragement and belief in my efforts to undertake this project. Finally, I would like to acknowledge those who took part in the research for this PhD thesis: Lord David Steel, Lord David Owen, Lord Chris Smith, Lord Andrew Adonis, Lord David Blunkett and Dame Caroline Spelman. 3 Abstract This thesis offers a distinctive and innovative framework for the study of effective official opposition politics in the United Kingdom. -

October 2019 50P Are You Ready? Brexit Looms

Issue 421 October 2019 50p Are you ready? Brexit looms ... & Chippy looks to the future Parliament is in turmoil and Chipping Norton, with the nation, awaits its fate, as the Mop Magic! Government plans to leave the EU on 31 October – Deal or No Deal. So where next? Is Chippy ready? It’s all now becoming real. Will supplies to Chippy’s shops and health services be disrupted? Will our townsfolk, used to being cut off in the snow, stock up just in case? Will our businesses be affected? Will our EU workers stay and feel secure? The News reports from around Chippy on uncertainty, contingency plans, but also some signs of optimism. Looking to the future – Brexit or not, a positive vision for Chippy awaits if everyone can work together on big growth at Tank Farm – but with the right balance of jobs, housing mix, and environmental sustainability for a 21st century Market town – and of course a solution to those HGV and traffic issues. Chipping Norton Town Council held a lively Town Hall meeting in September, urging the County Council leader, Ian Hudspeth into action to work with them. Lots more on Brexit, HGVs, and all this on pages 2-3. News & Features in this Issue • GCSE Results – Top School celebrates great results • Health update – GPs’ new urgent care & appoint- ment system • Cameron book launch – ‘For the Record’ • Chipping Norton Arts Festival – 5 October The Mop Fair hit town in • Oxfordshire 2050 – how will Chippy fit in? September – with everyone • Climate emergency – local action out having fun, while the traffic Plus all the Arts, Sports, Clubs, Schools and Letters went elsewhere. -

Brexit and Columns the Rhetorical Figures That Are Used in the Guardian and the Daily Mail

Arissen, s4341791/1 Brexit and Columns The Rhetorical Figures that are used in The Guardian and The Daily Mail Inge Arissen, s4341791 BA Thesis, English Literature August 2018 Supervisor: Chris Louttit Second Supervisor: Usha Wilbers Arissen, s4341791/2 ENGELSE TAAL EN CULTUUR Teacher who will receive this document: C. Louttit Title of document:Resubmission Thesis Name of course: Bachelor Thesis Date of submission: 5 August 2018 The work submitted here is the sole responsibility of the undersigned, who has neither committed plagiarism nor colluded in its production. Signed Name of student: Inge Arissen Student number: s4341791 Arissen, s4341791/3 Abstract This research will deal with newspapers and their columns on Brexit from January 2015 up till December 2016. The newspapers that will be discussed are The Guardian and The Daily Mail and their columnists John Crace and Stephen Glover. The rhetorical figures of each column are collected and the percentages of use is calculated. From these data, the most common rhetorical figures can be deduced and most their function will be described. To understand the theoretical frame of the research, background information on columns and interpreting rhetorical figures is given as well. The claim of this study is that each author uses different rhetorical devices in their columns, since their both on a different side in the Brexit discussion. Key Words: Brexit; Columns; Rhetorical Figures; The Guardian; The Daily Mail; Politics Arissen, s4341791/4 Table of Content Introduction …………………………………………………………………………….p5 -

Human Rights Annual Report 2005

House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee Human Rights Annual Report 2005 First Report of Session 2005–06 HC 574 House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee Human Rights Annual Report 2005 First Report of Session 2005–06 Report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 15 February 2006 HC 574 Published on 23 February 2006 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 Foreign Affairs Committee The Foreign Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the administration, expenditure and policy of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and its associated agencies. Current membership Mike Gapes (Labour, Ilford South), Chairman Mr Fabian Hamilton (Labour, Leeds North East) Rt Hon Mr David Heathcoat-Amory (Conservative, Wells) Mr John Horam (Conservative, Orpington) Mr Eric Illsley (Labour, Barnsley Central) Mr Paul Keetch (Liberal Democrat, Hereford) Andrew Mackinlay (Labour, Thurrock) Mr John Maples (Conservative, Stratford-on-Avon) Sandra Osborne (Labour, Ayr, Carrick and Cumnock) Mr Greg Pope (Labour, Hyndburn) Mr Ken Purchase (Labour, Wolverhampton North East) Rt Hon Sir John Stanley (Conservative, Tonbridge and Malling) Ms Gisela Stuart (Labour, Birmingham Edgbaston) Richard Younger-Ross (Liberal Democrat, Teignbridge) The following member was also a member of the committee during the parliament. Rt Hon Mr Andrew Mackay (Conservative, Bracknell) Powers The committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. -

Case Study on the United Kingdom and Brexit Juliane Itta & Nicole Katsioulis the Female Face of Right-Wing Populism and Ex

Triumph of The women? The Female Face of Right-wing Populism and Extremism 02 Case study on the United Kingdom and Brexit Juliane Itta & Nicole Katsioulis 01 Triumph of the women? The study series All over the world, right-wing populist parties continue to grow stronger, as has been the case for a number of years – a development that is male-dominated in most countries, with right-wing populists principally elected by men. However, a new generation of women is also active in right-wing populist parties and movements – forming the female face of right-wing populism, so to speak. At the same time, these parties are rapidly closing the gap when it comes to support from female voters – a new phenomenon, for it was long believed that women tend to be rather immune to right-wing political propositions. Which gender and family policies underpin this and which societal trends play a part? Is it possible that women are coming out triumphant here? That is a question that we already raised, admittedly playing devil’s advocate, in the first volume of the publication, published in 2018 by the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Triumph of the women? The Female Face of the Far Right in Europe. We are now continuing this first volume with a series of detailed studies published at irregular intervals. This is partly in response to the enormous interest that this collection of research has aroused to date in the general public and in professional circles. As a foundation with roots in social democracy, from the outset one of our crucial concerns has been to monitor anti-democratic tendencies and developments, while also providing information about these, with a view to strengthening an open and democratic society thanks to these insights. -

Please Note That This Is BBC Copyright and May Not Be Reproduced Or Copied for Any Other Purpose

Please note that this is BBC copyright and may not be reproduced or copied for any other purpose. RADIO 4 CURRENT AFFAIRS ANALYSIS LABOUR, THE LEFT AND EUROPE TRANSCRIPT OF A RECORDED DOCUMENTARY Presenter: Edward Stourton Producer: Chris Bowlby Editor: Innes Bowen BBC W1 NBH 04B BBC Broadcasting House Portland Place LONDON W1A 1AA 020 3 361 4420 Broadcast Date: 29.10.12 2030-2100 Repeat Date: 04.05.12 2130-2200 CD Number: Duration: 27.45 1 Taking part in order of appearance: Gisela Stuart Labour MP Charles Grant Director of Centre for European Reform Roger Liddle Labour Member of House of Lords Chair of Policy Network think tank Brian Brivati Historian of Labour Party Visiting Professor, Kingston University Thomas Docherty Labour MP 2 STUART: We’ve now got 27 countries locked together, and some of those locked into a single currency, in a way which will not address the original problem. Far from it. If you turn on your television sets and watch what’s happening in Greece, what may well happen in Spain and Italy, a deep resentment of the Germans who are currently damned if they do and damned if they don’t. I’m just so sad about it because it didn’t need to happen that way. STOURTON: The MP Gisela Stuart has the kind of background that should make her a solid member of Labour’s pro-European mainstream; she is German by birth and on the right of the party. But in an interview for this programme she has gone public with a view that is, by her own account, regarded as “heresy” on the Labour benches. -

An Analysis of John Peel's Radio Talk and Career At

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2008 The Power of a Paradoxical Persona: An Analysis of John Peel’s Radio Talk and Career at the BBC Richard P. Winham University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Winham, Richard P., "The Power of a Paradoxical Persona: An Analysis of John Peel’s Radio Talk and Career at the BBC. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2008. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/440 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Richard P. Winham entitled "The Power of a Paradoxical Persona: An Analysis of John Peel’s Radio Talk and Career at the BBC." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Communication and Information. Paul Ashdown, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Barbara Moore, Naeemah Clark, Michael Keene Accepted for the Council: -

1 Getting Our Country Back. the UK Press on the Eve of the EU Referendum. the Discourse of Ellipsis Over Immigration and The

1 Getting our country back. The UK press on the eve of the EU referendum. The discourse of ellipsis over immigration and the challenging of the British collective memory over Europe. Dr Paul Rowinski. University of Bedfordshire. Abstract (edited). This paper investigates a critical discourse analysis the author has conducted of UK mainstream newspaper coverage on the eve of the EU referendum. Immigration became a key issue in the closing days. The paper will explore the possibility that the discourse moved from persuasion to prejudice and xenophobia. The paper will also argue that in the age of populist post-truth politics, some of the newspapers also employed such emotive rhetoric, designed to influence and compel the audience to draw certain conclusions – to get their country back. In so doing, it is argued some of the UK media also pose a serious threat to democracy and journalism – rather than holding those in power to account and maintaining high journalistic standards. The notion that that some of the UK media played on public perceptions and a collective memory that has created, propagated and embedded many myths about the EU for decades, is explored. The possibility this swayed many – despite limited or a lack of substantiation, is explored, a discourse of ellipsis, if you will. 2 Introduction. This paper will seek to demonstrate how the use language in Britain’s EU referendum did shift from that of persuasion to that of overt prejudice and xenophobia. This paper will also seek to demonstrate how some of the British newspapers replaced the truth and objective facts with pro-Brexit emotive rhetoric, typical of the post-truth politics of the age. -

Framing Immigration During the Brexit Campaign

Unsustainable and Uncontrolled: Framing Immigration During the Brexit Campaign Jessica Van Horne A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in International Studies University of Washington 2018 Committee: Kathie Friedman, Chair Scott Fritzen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: International Studies – Jackson School © Copyright 2018 Jessica Van Horne University of Washington Abstract Unsustainable and Uncontrolled: Framing Immigration During the Brexit Campaign Jessica Marie Van Horne Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Kathie Friedman, Associate Professor International Studies The British vote to leave the European Union in 2016 came as a major surprise to politicians and scholars. Pre-referendum scholarship indicated that while British voters had concerns about cultural issues, such as identity and immigration, they would ultimately decide based on economic considerations. However, post-referendum voter surveys and scholarship showed that immigration was a key issue for many Leave and Undecided voters. This paper addresses why immigration was such a significant issue, and why it was so closely tied to leaving the EU, by discussing how the official campaigns and print media sources prioritized and characterized the issue. I argue that the relative prominence of immigration in media coverage, and the increased likelihood that newspapers would use Leave-associated frames, which also corresponded with pre-existing negative attitudes towards immigrants, contributed to immigration’s overall -

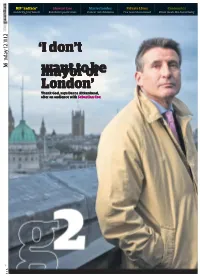

T Want to Be Mayor of London

RIP *sadface* Stewart Lee Mastectomies Private Lives Enonomics Celebrity grief tweets Rekebah’s poetic texts Cancer risk dilemma I’ve never been kissed Brian meets Ha-Joon Chang 1 2 1 . 1 . 1 2 y a ‘I don’t d n M o mayor want to of be London’ Thank God, says Decca Aitkenhead, after an audience with Sebastian Coe A 2 1 Shortcuts l i v e D u n n R I P C e s f o r a l l t h Eulogies t h a n k Gervais and Radio 1 DJ Greg James, n j o y m e n t o u r s o f e neither of whom I believe to have h D a d ’ s Reaping the w a t c h i n g been particular acquaintances of A r m y Nutkins, or, indeed, luminaries in Celebrity Death the wildlife-broadcasting world. Twitter Harvest Unless we count Flanimals. This year we have encountered the high-profile passings of Neil So sad to hear Armstrong, Tony Scott and Hal t is often suggested that the David, and naturally the coverage death of Diana, Princess of about Terry Nutkins. that followed them often drew on I Wales, altered the nature What an absolute celebrity tweets (“Everyone should of collective grief, rendering it icon go outside and look at the moon suddenly acceptable to line the tonight and give a thought to Neil streets, send flowers and, most Armstrong,” ordered McFly’s Tom importantly, weep publicly at the Fletcher). But few could match the death of someone you did not response that greeted the death of actually know. -

The Appointment and Conduct of Departmental Neds Dr Matthew Gill, Rhys Clyne and Grant Dalton

IfG INSIGHT | JULY 2021 The appointment and conduct of departmental NEDs Dr Matthew Gill, Rhys Clyne and Grant Dalton Matt Hancock’s appointment of Gina Coladangelo at the Department of Health and Social Care has amplified concerns about the role of non-executive directors in Whitehall departments. This paper sets out how the government should improve the governance surrounding the appointment and activity of departmental NEDs to restore public confidence in the role they play. Introduction Non-executive directors on the boards of government departments (departmental NEDs) have been an overlooked element of Whitehall’s governance. Because executive power rests with ministers, supported by the civil service, it has been tempting to think of departmental boards as a side issue. Those boards do not have the executive power of company boards in the private sector, nor should they. But they can be a valuable source of expertise and a route to strengthening governance. 1 DEPARTMENTAL NEDs Departmental NEDs are tasked with advising on important aspects of departmental affairs – recruitment, management, risk – and can recommend to the prime minister the sacking of the permanent secretary. They chair departments’ audit and risk committees, a significant function taken seriously in Whitehall. They also have considerable access to people and information and, in some cases, influence with ministers. In his recent speech on government reform Michael Gove argued that departmental NEDs are an important source of “new perspectives” and “enhanced scrutiny” for departments.1 That means it is important to appoint people capable of performing those roles effectively, and for their role to be clear. -

The Convention in the Future of Europe: the Deliberating Phase

RESEARCH PAPER 03/16 The Convention on the 14 FEBRUARY 2003 Future of Europe: the deliberating phase “The Euro train is still rushing through the night, and is clearly going to the terminus in the Euro state. I would like to think that our representatives might cast a few of those British leaves on the line to slow it down a little and make the journey more attractive”.(John Redwood, Standing Committee on the Convention, 23 October 2002) “I not only occasionally scatter British leaves on the track, but I scatter them with the best native Bavarian accent, which is even more effective”. (Gisela Stuart, UK Representative on the Convention, in reply) The Convention on the Future of Europe, chaired by Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, was launched in February 2002 to look into the future constitutional and institutional structure of the European Union. During 2002 ten Working Groups, established in accordance with the Laeken Declaration of December 2001, reported their conclusions to the Plenary. An eleventh Group reported in January 2003. The Praesidium presented a preliminary draft constitutional text in October 2002 and will now elaborate on this, taking into account the findings of the Working Groups and other contributions to the debate. The Convention is due to report its conclusions by June 2003. This Paper looks at the Convention process and the Working Group reports. It also considers the UK Government’s and Parliament’s response to the Working Group Final Reports and recommendations. Background information on the Convention and early proposals are discussed in Library Research Paper 02/14, The Laeken declaration and the Convention on the Future of Europe.