Bringing the Dictionary to the User: the FOKS System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to Kanbun: W4019x (Fall 2004) Mondays and Wednesdays 11-12:15, Kress Room, Starr Library (Entrance on 200 Level)

1 Introduction to Kanbun: W4019x (Fall 2004) Mondays and Wednesdays 11-12:15, Kress Room, Starr Library (entrance on 200 Level) David Lurie (212-854-5034, [email protected]) Office Hours: Tuesdays 2-4, 500A Kent Hall This class is intended to build proficiency in reading the variety of classical Japanese written styles subsumed under the broad term kanbun []. More specifically, it aims to foster familiarity with kundoku [], a collection of techniques for reading and writing classical Japanese in texts largely or entirely composed of Chinese characters. Because it is impossible to achieve fluent reading ability using these techniques in a mere semester, this class is intended as an introduction. Students will gain familiarity with a toolbox of reading strategies as they are exposed to a variety of premodern written styles and genres, laying groundwork for more thorough competency in specific areas relevant to their research. This is not a class in Classical Chinese: those who desire facility with Chinese classical texts are urged to study Classical Chinese itself. (On the other hand, some prior familiarity with Classical Chinese will make much of this class easier). The pre-requisite for this class is Introduction to Classical Japanese (W4007); because our focus is the use of Classical Japanese as a tool to understand character-based texts, it is assumed that students will already have control of basic Classical Japanese grammar. Students with concerns about their competence should discuss them with me immediately. Goals of the course: 1) Acquire basic familiarity with kundoku techniques of reading, with a focus on the classes of special characters (unread characters, twice-read characters, negations, etc.) that form the bulk of traditional Japanese kanbun pedagogy. -

ALTEC Language Class: Japanese Beginning II

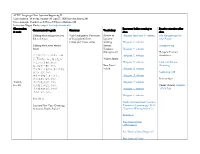

ALTEC Language Class: Japanese Beginning II Class duration: 10 weeks, January 28–April 7, 2020 (no class March 24) Class meetings: Tuesdays at 5:30pm–7:30pm in Hellems 145 Instructor: Megan Husby, [email protected] Class session Resources before coming to Practice exercises after Communicative goals Grammar Vocabulary & topic class class Talking about things that you Verb Conjugation: Past tense Review of Hiragana Intro and あ column Fun Hiragana app for did in the past of long (polite) forms Japanese your Phone (~desu and ~masu verbs) Writing Hiragana か column Talking about your winter System: Hiragana song break Hiragana Hiragana さ column (Recognition) Hiragana Practice クリスマス・ハヌカー・お Hiragana た column Worksheet しょうがつ 正月はなにをしましたか。 Winter Sports どこにいきましたか。 Hiragana な column Grammar Review なにをたべましたか。 New Year’s (Listening) プレゼントをかいましたか/ Vocab Hiragana は column もらいましたか。 Genki I pg. 110 スポーツをしましたか。 Hiragana ま column だれにあいましたか。 Practice Quiz Week 1, えいがをみましたか。 Hiragana や column Jan. 28 ほんをよみましたか。 Omake (bonus): Kasajizō: うたをききましたか/ Hiragana ら column A Folk Tale うたいましたか。 Hiragana わ column Particle と Genki: An Integrated Course in Japanese New Year (Greetings, Elementary Japanese pgs. 24-31 Activities, Foods, Zodiac) (“Japanese Writing System”) Particle と Past Tense of desu (Affirmative) Past Tense of desu (Negative) Past Tense of Verbs Discussing family, pets, objects, Verbs for being (aru and iru) Review of Katakana Intro and ア column Katakana Practice possessions, etc. Japanese Worksheet Counters for people, animals, Writing Katakana カ column etc. System: Genki I pgs. 107-108 Katakana Katakana サ column (Recognition) Practice Quiz Katakana タ column Counters Katakana ナ column Furniture and common Katakana ハ column household items Katakana マ column Katakana ヤ column Katakana ラ column Week 2, Feb. -

The Degree of the Speaker's Negative Attitude in a Goal-Shifting

In Christopher Brown and Qianping Gu and Cornelia Loos and Jason Mielens and Grace Neveu (eds.), Proceedings of the 15th Texas Linguistics Society Conference, 150-169. 2015. The degree of the speaker’s negative attitude in a goal-shifting comparison Osamu Sawada∗ Mie University [email protected] Abstract The Japanese comparative expression sore-yori ‘than it’ can be used for shifting the goal of a conversation. What is interesting about goal-shifting via sore-yori is that, un- like ordinary goal-shifting with expressions like tokorode ‘by the way,’ using sore-yori often signals the speaker’s negative attitude toward the addressee. In this paper, I will investigate the meaning and use of goal-shifting comparison and consider the mecha- nism by which the speaker’s emotion is expressed. I will claim that the meaning of the pragmatic sore-yori conventionally implicates that the at-issue utterance is preferable to the previous utterance (cf. metalinguistic comparison (e.g. (Giannakidou & Yoon 2011))) and that the meaning of goal-shifting is derived if the goal associated with the at-issue utterance is considered irrelevant to the goal associated with the previous utterance. Moreover, I will argue that the speaker’s negative attitude is shown by the competition between the speaker’s goal and the hearer’s goal, and a strong negativity emerges if the goals are assumed to be not shared. I will also compare sore-yori to sonna koto-yori ‘than such a thing’ and show that sonna koto-yori directly expresses a strong negative attitude toward the previous utterance. -

Writing As Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-Language Literature

At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2021 Reading Committee: Edward Mack, Chair Davinder Bhowmik Zev Handel Jeffrey Todd Knight Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Asian Languages and Literature ©Copyright 2021 Christopher J Lowy University of Washington Abstract At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Edward Mack Department of Asian Languages and Literature This dissertation examines the dynamic relationship between written language and literary fiction in modern and contemporary Japanese-language literature. I analyze how script and narration come together to function as a site of expression, and how they connect to questions of visuality, textuality, and materiality. Informed by work from the field of textual humanities, my project brings together new philological approaches to visual aspects of text in literature written in the Japanese script. Because research in English on the visual textuality of Japanese-language literature is scant, my work serves as a fundamental first-step in creating a new area of critical interest by establishing key terms and a general theoretical framework from which to approach the topic. Chapter One establishes the scope of my project and the vocabulary necessary for an analysis of script relative to narrative content; Chapter Two looks at one author’s relationship with written language; and Chapters Three and Four apply the concepts explored in Chapter One to a variety of modern and contemporary literary texts where script plays a central role. -

A Performer's Guide to Minoru Miki's Sohmon III for Soprano, Marimba and Piano (1988)

University of Cincinnati Date: 4/22/2011 I, Margaret T Ozaki-Graves , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Voice. It is entitled: A Performer’s Guide to Minoru Miki’s _Sohmon III for Soprano, Marimba and Piano_ (1988) Student's name: Margaret T Ozaki-Graves This work and its defense approved by: Committee chair: Jeongwon Joe, PhD Committee member: William McGraw, MM Committee member: Barbara Paver, MM 1581 Last Printed:4/29/2011 Document Of Defense Form A Performer’s Guide to Minoru Miki’s Sohmon III for Soprano, Marimba and Piano (1988) A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music by Margaret Ozaki-Graves B.M., Lawrence University, 2003 M.M., University of Cincinnati, 2007 April 22, 2011 Committee Chair: Jeongwon Joe, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Japanese composer Minoru Miki (b. 1930) uses his music as a vehicle to promote cross- cultural awareness and world peace, while displaying a self-proclaimed preoccupation with ethnic mixture, which he calls konketsu. This document intends to be a performance guide to Miki’s Sohmon III: for Soprano, Marimba and Piano (1988). The first chapter provides an introduction to the composer and his work. It also introduces methods of intercultural and artistic borrowing in the Japanese arts, and it defines the four basic principles of Japanese aesthetics. The second chapter focuses on the interpretation and pronunciation of Sohmon III’s song text. -

Section 18.1, Han

The Unicode® Standard Version 13.0 – Core Specification To learn about the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see http://www.unicode.org/versions/latest/. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and the publisher was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters or in all capitals. Unicode and the Unicode Logo are registered trademarks of Unicode, Inc., in the United States and other countries. The authors and publisher have taken care in the preparation of this specification, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. © 2020 Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. This publication is protected by copyright, and permission must be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction. For information regarding permissions, inquire at http://www.unicode.org/reporting.html. For information about the Unicode terms of use, please see http://www.unicode.org/copyright.html. The Unicode Standard / the Unicode Consortium; edited by the Unicode Consortium. — Version 13.0. Includes index. ISBN 978-1-936213-26-9 (http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode13.0.0/) 1. -

The Japanese Numeral Classifiers Hiki and Hatsu

Prototypes and Metaphorical Extensions: The Japanese Numeral Classifiers hiki and hatsu Hiroko Komatsu A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2018 Department of Japanese Studies School of Languages and Cultures Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of Sydney This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources have been acknowledged. Name: Hiroko Komatsu Signature: ……………………….. Date: ……..31 January 2018……. Abstract This study concerns the meaning of Japanese numeral classifiers (NCs) and, particularly, the elements which guide us to understand the metaphorical meanings they can convey. In the typological literature, as well as in studies of Japanese, the focus is almost entirely on NCs that refer to entities. NCs are generally characterised as being matched with a noun primarily based on semantic criteria such as the animacy, the physical characteristics, or the function of the referent concerned. However, in some languages, including Japanese, nouns allow a number of alternative NCs, so that it is considered that NCs are not automatically matched with a noun but rather with the referent that the noun refers to in the particular context in which it occurs. This study examines data from the Balanced Corpus of Contemporary Written Japanese, and focuses on two NCs as case studies: hiki, an entity NC, typically used to classify small, animate beings, and hatsu, an NC that is used to classify both entities and events that are typically explosive in nature. -

Hasegawasoliloquych2.Pdf

ne yo Sentence-final particles ne yo ne Yo ne yo ne yo ne yo ne yo ne ne yo ne yo Yoku furu ne/yo. Ne yo ne ne yo yo yo ne ne yo yo ne yo Sonna koto wa atarimae da ne/yo. Kimi no imooto-san, uta ga umai ne. ne Kushiro wa samui yo. Kyoo wa kinyoobi desu ne. ne ne Ne Ee, soo desu. Ii tenki da nee. Kyoo wa kinyoobi desu ne. ne Soo desu ne. Yatto isshuukan owarimashita ne. ne ne yo Juubun ja nai desu ka. Watashi to shite wa, mitomeraremasen ne. Chotto yuubinkyoku e itte kimasu ne. Ee, boku wa rikugun no shichootai, ima no yusoobutai da. Ashita wa hareru deshoo nee. shichootai yusoobutai Koshiji-san wa meshiagaru no mo osuki ne. ne affective common ground ne Daisuki. Oshokuji no toki ni mama shikaritaku nai kedo nee. Hitoshi no sono tabekata ni wa moo Denwa desu kedo/yo. ne yo yone Ashita irasshaimasu ka/ne. yo yone ne yo the coordination of dialogue ne Yo ne A soonan desu ka. Soo yo. Ikebe-san wa rikugun nandesu yone. ne yo ne yo ne yo ne Ja, kono zasshi o yonde-miyoo. Yo Kore itsu no zasshi daroo. A, nihon no anime da. procedural encoding anime ne yo A, kono Tooshiba no soojiki shitteru. Hanasu koto ga nakunatchatta. A, jisho wa okutta. Kono hon zuibun furui. Kyoo wa suupaa ni ikanakute ii. ka Kore mo tabemono. wa Dansu kurabu ja nakute shiataa. wa↓ wa wa↑ na Shikakui kuruma-tte suki janai. -

Enclosed CJK Letters and Months Range: 3200–32FF

Enclosed CJK Letters and Months Range: 3200–32FF This file contains an excerpt from the character code tables and list of character names for The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 This file may be changed at any time without notice to reflect errata or other updates to the Unicode Standard. See https://www.unicode.org/errata/ for an up-to-date list of errata. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/ for access to a complete list of the latest character code charts. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/Unicode-14.0/ for charts showing only the characters added in Unicode 14.0. See https://www.unicode.org/Public/14.0.0/charts/ for a complete archived file of character code charts for Unicode 14.0. Disclaimer These charts are provided as the online reference to the character contents of the Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 but do not provide all the information needed to fully support individual scripts using the Unicode Standard. For a complete understanding of the use of the characters contained in this file, please consult the appropriate sections of The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0, online at https://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode14.0.0/, as well as Unicode Standard Annexes #9, #11, #14, #15, #24, #29, #31, #34, #38, #41, #42, #44, #45, and #50, the other Unicode Technical Reports and Standards, and the Unicode Character Database, which are available online. See https://www.unicode.org/ucd/ and https://www.unicode.org/reports/ A thorough understanding of the information contained in these additional sources is required for a successful implementation. -

The Textile Terminology in Ancient Japan

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Centre for Textile Research Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD 2017 The exT tile Terminology in Ancient Japan Mari Omura Gangoji Institute for Research of Cultural Property Naoko Kizawa Gangoji Institute for Research of Cultural Property Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/texterm Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons, Classical Literature and Philology Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Indo-European Linguistics and Philology Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, Museum Studies Commons, Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons, and the Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Omura, Mari and Kizawa, Naoko, "The exT tile Terminology in Ancient Japan" (2017). Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD. 28. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/texterm/28 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Centre for Textile Research at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The Textile Terminology in Ancient Japan Mari Omura, Gangoji Institute for Research of Cultural Property Naoko Kizawa, Gangoji Institute for Research of Cultural Property In Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD, ed. Salvatore Gaspa, Cécile Michel, & Marie-Louise Nosch (Lincoln, NE: Zea Books, 2017), pp. -

IEEE 802.1 Interim Meeting Hiroshima, Japan January 2019

IEEE 802.1 Interim Meeting Hiroshima, Japan January 2019 1 Event Meeting dates January 14, 2019-January 18, 2019 Venue and location Hiroshima Oriental Hotel in Hiroshima 6-10, Tanakamachi, Naka-ku, Hiroshima, Japan 730-0026 http://oriental-hiroshima-jp.book.direct/en-gb Booked rooms are available on September 19, 2018(JST). https://asp.hotel-story.ne.jp/ver3d/plan.asp?p=A2ONG&c1=64101&c2=001 Please note: Check in starts from 2:00 p.m.. On your day of departure, you have time to leave your room until 11:00 a.m.. Early check-in and late check-out costs a thousand yen per. 2 Meeting registration Registration has to be done via website : https://www.regonline.com/builder/site/?eventid=2235732 Registration Fees - Early bird registration USD 700 Open on September 19 until November 16, 2018(PST) - Standard registration USD 800 From November 17, 2018 to January 4, 2019(PST) - Late/on Site registration USD 900 Open after January 4, 2019 to January 18, 2019(PST) The registration fee covers meeting fee, refreshments, coffee breaks, lunch, social event and Wi-Fi. Note: The registration fee includes VAT. Fee will be independent from staying at the meeting hotel. Registration payment policy Registration is payable through a secure website and requires a valid credit card for the payment of the registration fee; cash and checks are NOT accepted for registration. Any individual who attends any part of the IEEE 802.1 Interim Meeting must register and pay the full session fee. Session registrations are not transferable to another individual or to another interim session. -

Multiple Indexing in an Electronic Kanji Dictionary James BREEN Monash University Clayton 3800, Australia [email protected]

Multiple Indexing in an Electronic Kanji Dictionary James BREEN Monash University Clayton 3800, Australia [email protected] Abstract and contain such information as the classification of the character according to Kanji dictionaries, which need to present a shape, usage, components, etc., the large number of complex characters in an pronunciation or reading of the character, order that makes them accessible by users, variants of the character, the meaning or traditionally use several indexing techniques semantic application of the character, and that are particularly suited to the printed often a selection of words demonstrating the medium. Electronic dictionary technology use of the character in the language's provides the opportunity of both introducing orthography. These dictionaries are usually new indexing techniques that are not ordered on some visual characteristic of the feasible with printed dictionaries, and also characters. allowing a wide range of index methods with each dictionary. It also allows A typical learner of Japanese needs to have dictionaries to be interfaced at the character both forms of dictionary, and the process of level with documents and applications, thus "looking up" an unknown word often removing much of the requirement for involves initially using the character complex index methods. This paper surveys dictionary to determine the pronunciation of the traditional indexing methods, introduces one or more of the characters, then using some of the new indexing techniques that that pronunciation as an index to a word have become available with electronic kanji dictionary, in a process that can be time- dictionaries, and reports on an analysis of consuming and error-prone.