Zmiany Struktury Funkcjonalno

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Web Portal Z P R R P Wojennych Ie I Z BRZESKA M R R N S a Ł R H O Z R Żo EJOW LUBLIN B O IECK Palaces and Mansions; Museums P M E A

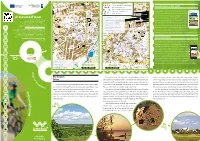

a g u ł D B hemiczna i C iego e lsk W Ch Po ł emiczn wa ojska a a o y Targ W w g i n o zafirowa n ów S irak yb A S C . a k F AL. PRZYJAŹN h o I a r s ł East of Poland Cycling Trail Green Velo e a y a TERESPOL g i c s w m z E373 z 12 u y c 816 n o ł a n i t K r c i I DOROHUSK z y - m a D o N s z A M e Churches; cloisters; Orthodox churches;w synagogues Ż Ź d na s k n N cz L a z a A Cmentarz Jeńców i a n o t ł a W o ar z oc r J T . łn O y ó d a P e Y www.greenvelo.pl web portal z p R r P Wojennych ie i Z BRZESKA M r r n s A ł R H o z R Żo EJOW LUBLIN B o IECK Palaces and mansions; museums P M e A A A K w . L S w U . ZEA P BRSK G 82 B E R L K 12 PA Z a EL E373 A A RAPMA BR s S REJ M S o KA OW RA Żytnia a IECK k A A a Z SK ł g L ł E i Hotels; tourist information centres; parking facilities B n e ą z A . U K u L ES Z ł a R t d g B iN c PA J a AM W o R o m k D R zy KA . -

Arkusz ORZECHÓW NOWY (715)

PA Ń STWOWY INSTYTUT GEOLOGICZNY PA Ń STWOWY INSTYTUT BADAWCZY OPRACOWANIE ZAMÓWIONE PRZEZ MINISTRA Ś R O D O W I S K A OBJAŚNIENIA DO MAPY GEOŚRODOWISKOWEJ POLSKI 1:50 000 Arkusz ORZECHÓW NOWY (715) Warszawa 2011 Autor planszy A: Barbara Ptak* Autorzy planszy B: Izabela Bojakowska*, Paweł Kwecko*, Jerzy Miecznik*, Stanisław Marszałek** Główny koordynator MGśP: Małgorzata Sikorska-Maykowska* Redaktor regionalny planszy A: Katarzyna Strzemińska* Redaktor regionalny planszy B: Joanna Szyborska-Kaszycka * Redaktor tekstu: Joanna Szyborska-Kaszycka* *Państwowy Instytut Geologiczny – Państwowy Instytut Badawczy, ul. Rakowiecka 4, 00-975 Warszawa ** Przedsiębiorstwo Geologiczne POLGEOL SA, ul. Berezyńska 39, 03-908 Warszawa ISBN ...................... Copyright by PIG and MŚ, Warszawa 2011 Spis treści I. Wstęp – B. Ptak ........................................................................................................ 3 II. Charakterystyka geograficzna i gospodarcza – B. Ptak .......................................... 4 III. Budowa geologiczna – B. Ptak .............................................................................. 7 IV. ZłoŜa kopalin – B. Ptak........................................................................................ 11 1. Węgiel kamienny – B. Ptak................................................................................ 11 2. Piaski – B. Ptak .................................................................................................. 15 3. Torfy – B. Ptak.................................................................................................. -

Landscapes of the West Polesie Regional Identity and Its Transformation Over Last Half Century

International Consortium ALTER-Net Environmental History Project University of Life Sciences in Lublin Department of Landscape Ecology and Nature Conservation Polesie National Park LANDSCAPES OF THE WEST POLESIE REGIONAL IDENTITY AND ITS TRANSFORMATION OVER LAST HALF CENTURY Authors: Tadeusz J. Chmielewski, Szymon Chmielewski, Agnieszka Kułak, Malwina Michalik-ŚnieŜek, Weronika Maślanko International Coordinator of the ALTER-Net Environmental History Project: Andy Sier Lublin – Urszulin 2015 Affiliation Tadeusz J. Chmielewski, Agnieszka Kułak, Weronika Maślanko, Malwina Michalik-ŚnieŜek: University of Life Sciences in Lublin, Department of Landscape Ecology and Nature Conservation Szymon Chmielewski: Contents University of Life Sciences in Lublin, Institute of Soil Science, Engineering and Environmental Management Andy Sier 1. Introduction …………………………………………………………………….………....4 Centre of Ecology & Hydrobiology; Lancaster Environmental Centre; Lancaster, UK 2. Characteristic of the Polish study area …………………………………….……….……..7 3. The unique landscape identity of the West Polesie region…………………..…………..21 4. Changes in land use structure and landscape diversity in the area of the ‘West The reviewers Polesie’ Biosphere Reserve over a last half century ….……………….....…...……...….43 Prof. UAM dr hab. Andrzej Macias 5. A model of landscape ecological structure in the central part of the Biosphere Reserve..79 Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań 6. A preliminary assessment of landscape physiognomy changes of West Polesie Institute of Physical Geography and Environmental Planning from the half of the 19th century to the beginning of the 21st century ………………..…91 7. A preliminary evaluation of changes in landscape services potential ………………....109 Prof. SGGW dr hab. Barbara śarska 8. Conclusions …………………………………………………………………………….115 Warsaw University of Life Sciences SGGW, 9. References………………………………………………………………………………119 Department of Environmental Protection Cover graphic design Agnieszka Kułak Photographs on the cover Tadeusz J. -

(EU) 2020/114 of 24 January 2020 Amending

Changes to legislation: Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2020/114 is up to date with all changes known to be in force on or before 28 December 2020. There are changes that may be brought into force at a future date. Changes that have been made appear in the content and are referenced with annotations. (See end of Document for details) View outstanding changes Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2020/114 of 24 January 2020 amending the Annex to Implementing Decision (EU) 2020/47 on protective measures in relation to highly pathogenic avian influenza of subtype H5N8 in certain Member States (notified under document C(2020) 487) (Text with EEA relevance) COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING DECISION (EU) 2020/114 of 24 January 2020 amending the Annex to Implementing Decision (EU) 2020/47 on protective measures in relation to highly pathogenic avian influenza of subtype H5N8 in certain Member States (notified under document C(2020) 487) (Text with EEA relevance) THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION, Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Having regard to Council Directive 89/662/EEC of 11 December 1989 concerning veterinary checks in intra-Community trade with a view to the completion of the internal market(1), and in particular Article 9(4) thereof, Having regard to Council Directive 90/425/EEC of 26 June 1990 concerning veterinary checks applicable in intra-Union trade in certain live animals and products with a view to the completion of the internal market(2), and in particular Article 10(4) thereof, Whereas: (1) Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2020/47(3) was adopted following outbreaks of highly pathogenic avian influenza of subtype H5N8 in holdings where poultry are kept in Poland, Slovakia, Hungary and Romania (the concerned Member States), and the establishment of protection and surveillance zones by the competent authority of the concerned Member States in accordance with Council Directive 2005/94/EC(4). -

COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING DECISION (EU) 2020/47 of 20

21.1.2020 EN Offi cial Jour nal of the European Union L 16/31 COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING DECISION (EU) 2020/47 of 20 January 2020 on protective measures in relation to highly pathogenic avian influenza of subtype H5N8 in certain Member States (notified under document C(2020) 344) (Text with EEA relevance) THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION, Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Having regard to Council Directive 89/662/EEC of 11 December 1989 concerning veterinary checks in intra-Community trade with a view to the completion of the internal market (1), and in particular Article 9(3) and (4) thereof, Having regard to Council Directive 90/425/EEC of 26 June 1990 concerning veterinary checks applicable in intra-Union trade in certain live animals and products with a view to the completion of the internal market (2), and in particular Article 10(3) and (4) thereof, Whereas: (1) Avian influenza is an infectious viral disease in birds, including poultry or other captive birds. Infections with avian influenza viruses in birds cause two main forms of that disease that are distinguished by their virulence. The low pathogenic form generally only causes mild symptoms, while the highly pathogenic form results in very high mortality rates in most poultry species. That disease may have a severe impact on the profitability of poultry farming causing disturbance to trade within the Union and exports to third countries. (2) Avian influenza is mainly found in birds, but under certain circumstances infections can also occur in humans even though the risk is generally very low. -

Możliwości Rozwoju Turystyki Na Obszarach Przyrodniczo Cennych Na Przykładzie Gminy Sosnowica

SIM23:Makieta 1 12/10/2009 3:30 PM Strona 50 MOŻLIWOŚCI ROZWOJU TURYSTYKI NA OBSZARACH PRZYRODNICZO CENNYCH NA PRZYKŁADZIE GMINY SOSNOWICA Monika Hurba Streszczenie Rozwój turystyki na obszarach przyrodniczo cennych musi uwzględniać szereg ograniczeń związanych z występowaniem obszarów chronionych. W artykule omówiono potencjał rozwojowy gminy Sosnowica, położonej w prawie 70% na terenach objętych różnymi formami ochrony przy - rody. Przedstawiono także główne założenia projektu pn. „Opracowanie innowacyjnego planu roz - woju gminy Sosnowica opartego na posiadanym potencjale i czynnym wykorzystaniu transferu wiedzy” współfinansowanego ze środków Europejskiego Funduszu Społecznego w ramach ZPORR oraz Budżetu Państwa, zrealizowanego przez władze samorządowe w celu lepszego zarządzania gminą Sosnowica zgodnie z zasadami zrównoważonego rozwoju. Słowa kluczowe: plan rozwoju, Sosnowica THE GROWTH POTENTIAL OF TOURISM IN VALUABLE NATURAL AREAS IN THE EXAMPLE OF SOSNOWICA MUNICIPALITY. Abstract Tourism development on valuable natural areas must take into account a number of limitations associated with the occurrence of protected areas. The article discusses the potential for develop - ment of the Sosnowica municipality, located in almost 70% on the areas covered by different forms of nature conservation. It also provides the main objectives of the project entitled "Developing an innovative plan for the development of Sosnowica community based on possessed potential and ac - tive use of knowledge transfer" co-funded by the European Social Fund under the Integrated Re - gional Operational Program and the State Budget, made by local authorities to better manage the Sosnowica municipality in accordance with the principles of sustainable development. Key words: development plan, Sosnowica Wstęp Współczesna ochrona przyrody w coraz większym stopniu postrzega obszary chronione jako na - rzędzie ochrony różnorodności biologiczne, ważnej nie tylko dla specjalistów przyrodników ale także dla szerszych grup społecznych. -

The History of Changes in Water Relations in the Catchment Basin of River Piwonia

Teka Kom. Ochr. Kszt. ĝrod. Przyr. – OL PAN, 2013, 10, 123–131 THE HISTORY OF CHANGES IN WATER RELATIONS IN THE CATCHMENT BASIN OF RIVER PIWONIA Antoni Grzywna Department of Land Reclamation and Agriculture Buildings, University of Live Sciences in Lublin Leszczynskiego str. 7, [email protected]. Co-financed by National Fund for Environmental Protection and Water Management Summary. The paper presents the history of changes in water relations in the catchment basin of river Piwonia. The changes in the layout and density of the river network are presented on the basis of topographic maps at the scale of 1 : 100 000 from the period from 1839 to 2009 and melioration plans. In the middle of the 19th century the river began on the meadows in the region of the village Górki, and the first melioration works were performed after 1890. After World War I fishpond farming developed in the area, as the existence of fishponds granted protection of estates from parcelling out. At that time 3 complexes appeared, composed of 25 fishponds in Sosnowica, 23 in Libiszów and 7 in Pieszowola. The greatest changes in water relations took place in the period of 1954–1961, when the Wieprz-Krzna Canal (WKC) was constructed, and in the valley of river Piwonia several melioration objects appeared, with surface area of about 4000 ha. In the 1960’s a water canal constituting the beginning of Lower Piwonia was constructed, bypassing lakes àukie and Bikcze from the east and lake Nadrybie from the north. As a result of hydrotechnical works, the length of the river increased from 40 to 62.7 km, and its beginning was shifted to lake UĞciwierzek. -

K I E R U N K I

WÓJT GMINY SOSNOWICA ZMIANA STUDIUM UWARUNKOWAŃ I KIERUNKÓW ZAGOSPODAROWANIA PRZESTRZENNEGO GMINY SOSNOWICA K I E R U N K I 21 - 500 Biała Podlaska Plac Szkolny Dwór 28 tel. [0-83] 342-00-36, fax 342-00-38 BIAŁA PODLASKA 2011 r. 1 WÓJT GMINY SOSNOWICA BIURO PROJEKTOWE „arch – dom”s.j. W BIAŁEJ PODLASKIEJ ZMIANA STUDIUM UWARUNKOWA Ń I KIERUNKÓW ZAGOSPODAROWANIA PRZESTRZENNEGO GMINY SOSNOWICA K I E R U N K I ZAŁ ĄCZNIK NR 3 Do Uchwały Nr V/2811 Rady Gminy Sosnowica z dnia 16 marca 2011 r. BIAŁA PODLASKA 2011 r. 2 Spis tre ści: 1 Cele rozwoju społeczno – gospodarczego gminy Sosnowica. _____________________ 7 2 Priorytety rozwojowe gminy Sosnowica. _____________________________________ 8 3 Funkcje gminy._________________________________________________________ 8 4 Hierarchia sieci osadniczej gminy. _________________________________________ 9 5 Zagospodarowanie przestrzenne.___________________________________________ 9 5.1 Struktura funkcjonalno – przestrzenna. _____________________________________ 9 5.2 Jednostki strukturalno osadnicze. _________________________________________ 10 5.3 Jednostki strukturalno rolniczo- le śne. _____________________________________ 11 6 Ochrona środowiska. ___________________________________________________ 11 6.1 Ochrona środowiska w aspekcie uwarunkowa ń prawnych. ____________________ 11 6.1.1 Obszary chronione. ___________________________________________________________ 11 6.1.2 „Poleski Park Narodowy” ______________________________________________________ 12 6.1.3 „Poleski Park Krajobrazowy” i „Park Krajobrazowy Pojezierze Ł ęczy ńskie” ______________ 13 6.1.4 „Ostoje siedliskowe i ptasie zakwalifikowane do Sieci Ekologicznej NATURA 2000” ______ 15 6.1.5 „Poleski Obszar Chronionego Krajobrazu”_________________________________________ 16 6.1.6 Rezerwat przyrody „Torfowisko przy Jeziorze Czarnym Sosnowickim”. _________________ 19 6.2 Przyrodniczy System Gminy Sosnowica.____________________________________ 20 6.2.1 Delimitacja Przyrodniczego Systemu Gminy Sosnowica. _____________________________ 20 6.2.1.1 Obszary w ęzłowe. -

Dzielnicowi Kpp W Parczewie

KPP PARCZEW https://parczew.policja.gov.pl/lpa/dzielnicowi/64813,Dzielnicowi-KPP-w-Parczewie.html 2021-10-05, 13:46 DZIELNICOWI KPP W PARCZEWIE Dzielnicowi Komendy Powiatowej Policji w Parczewie Rejon numer 1 Miasto i Gmina Parczew sierżant sztabowy Katarzyna Woźniak telefon 734 407 372 lub 47 814 32 50 adres poczty elektronicznej:[email protected] UWAGA! Podany adres mailowy ułatwi Ci kontakt z dzielnicowym, ale nie służy do składania zawiadomienia o przestępstwie, wykroczeniu, petycji wniosków ani skarg w rozumieniu przepisów Kontakt osobisty: Komenda Powiatowa Policji w Parczewie ul. Wojska Polskiego 4 pokój numer 8 Obsługuje rejon miasta Parczew w skład którego wchodzą następujące ulice miasta : 11 Listopada,1 Maja, Akacjowa, Armii Krajowej, Batalionów Chłopskich,Brzozowa, Bukowa, Dębowa, Działkowa, Jaworowa, Jodłowa, Kardynała Wyszyńskiego, Kościelna nr nieparzyste, Kościuszki, Krótka, Kwiatowa, Łąkowa, Lipowa, Lubartowska, Miodowa, Nadwalna, Nowa, Nowowiejska, Parkowa, Partyzantów, PCK, Piwonia, Plac Wolności, Słoneczna, Sosnowa, Spadochroniarzy, Świerkowa, Szeroka, Szkolna, Tęczowa, Włodawska, Wodociągowa, Zwycięstwa. Miejscowości wchodzące w skład gminy Parczew: Jasionka, Królewski Dwór, Michałówka, Przewłoka, Wierzbówka, Wola Przewłocka, Zaniówka INFORMACJA O REALIZACJI ZADAŃ PRIORYTETOWYCH NFORMACJA O REALIZACJI ZADAŃ PRIORYTETOWYCH - wersja edytowalna Rejon numer 2 Miasto i Gmina Parczew aspirant Piotr Szczygielski telefon 798 003 584 lub 47 814 32 50 adres poczty elektronicznej:[email protected] UWAGA! Podany adres mailowy ułatwi Ci kontakt z dzielnicowym, ale nie służy do składania zawiadomienia o przestępstwie, wykroczeniu, petycji wniosków ani skarg w rozumieniu przepisów Dzielnicowy odbiera pocztę w godzinach swojej służby. W sprawach niecierpiących zwłoki zadzwoń pod nr 997 lub 112 albo skontaktuj się z dyżurnym numer 83 355 32 10 Kontakt osobisty: Komenda Powiatowa Policji w Parczewie ul. -

Uchwala Nr VIII/50/19 Z Dnia 28 Czerwca 2019 R

DZIENNIK URZĘDOWY WOJEWÓDZTWA LUBELSKIEGO Lublin, dnia 8 sierpnia 2019 r. Poz. 4703 UCHWAŁA NR VIII/50/19 RADY GMINY SOSNOWICA z dnia 28 czerwca 2019 r. w sprawie uchwalenia Statutu Gminy Sosnowica Na podstawie art. 3 ust.1, art. 18 ust. 2 pkt 1, art. 40 ust. 2 pkt 1 i art. 41 ust.1 ustawy z dnia 8 marca 1990r. o samorządzie gminnym (Dz. U. z 2019 r., poz. 506) - Rada Gminy Sosnowica uchwala, co następuje: § 1. Uchwala się Statut Gminy Sosnowica w brzmieniu stanowiącym załącznik do niniejszej uchwały. § 2. Traci moc uchwała Nr V/28/03 Rady Gminy Sosnowica z dnia 31 stycznia 2003r.w sprawie uchwalenia Statutu Gminy Sosnowica, zmieniona uchwałami: 1) Nr VI/31/07 Rady Gminy Sosnowica z dnia 30 marca 2007r. w sprawie zmiany Statutu Gminy Sosnowica; 2) Nr XVII/131/08 Rady Gminy Sosnowica z dnia 29 sierpnia 2008r. w sprawie zmiany Statutu Gminy Sosnowica; 3) Nr VII/53/11 Rady Gminy Sosnowica z dnia 16 czerwca 2011r. w sprawie zmian w Statucie Gminy Sosnowica. § 3. Wykonanie uchwały powierza się Wójtowi Gminy Sosnowica. § 4. Uchwała wchodzi w życie po upływie 14 dni od dnia ogłoszenia w Dzienniku Urzędowym Województwa Lubelskiego. Przewodniczący Rady Gminy Marek Chibowski Dziennik Urzędowy Województwa Lubelskiego – 2 – Poz. 4703 Załącznik Nr 1 do uchwały Nr VIII/50/19 Rady Gminy Sosnowica z dnia 28 czerwca 2019 r. Rozdział 1. Postanowienia ogólne § 1. Statut określa: 1) ustrój Gminy Sosnowica, 2) zasady tworzenia, łączenia, podziału i znoszenia jednostek pomocniczych Gminy Sosnowica, udziału przewodniczących tych jednostek w pracach rady gminy oraz uprawnienia jednostek pomocniczych Gminy Sosnowica do prowadzenia gospodarki finansowej w ramach budżetu gminy, 3) organizację wewnętrzną, tryb pracy Rady Gminy oraz jej komisji stałych i doraźnych, 4) zasady i tryb działania komisji rewizyjnej, 5) zasady i tryb działania komisji skarg, wniosków i petycji, 6) zasady działania klubów radnych, 7) tryb pracy Wójta Gminy Sosnowica, 8) zasady dostępu obywateli do dokumentów organów Gminy wytworzonych w ramach wykonywania zadań publicznych oraz korzystania z nich. -

SOSNOWICA Powiat Parczewski

Andrzej Wawryniuk Michał Gołoś Historia, gospodarka, polityka Wielki leksykon lubelsko-wołyńskiego pobuża GMINA SOSNOWICA powiat parczewski Chełm, 2009 Copyright by Wyższa Szkoła Stosunków Międzynarodowych i Komunikacji Społecznej w Chełmie Wydanie I Recenzenci: Prof. dr hab. Maria Marczewska-Rytko, Uniwersytet Marii Curie-Skłodowskiej w Lublinie, Prof. dr hab. Bogdan Jarosz, Narodowy Uniwersytet Wołyński im. Łesi Ukrainki w Łucku. Prof. dr hab. Jerzy Jaskiernia, Uniwersytet Humanistyczno-Przyrodniczy Jana Kochanowskiego w Kielcach. ISBN: 978-83-924909-8-2 Zdjęcia: Andrzej Wawryniuk Projekt okładki: Jacek Kasprzycki Na okładce: Mapa wojskowa z lat 30-tych XX wieku Korekta: Joanna Greczkowska Mapy udostępnili: Marek Zieliński: [email protected] Urząd Gminy w Sosnowicy Skład i druk: Drukarnia SEYKAM, 22-100 Chełm, ul. Lubelska 69, tel. 082 565 34 39 e-mail: [email protected] WSTĘP Opracowanie, które oddajemy do rąk czytelników, jest pilotażową publikacją zaplanowanego na wiele lat cyklu wydawniczego związanego z prowadzonymi w Zakładzie Stosunków Międzynarodowych, Pracowni Badań Stosunków Polski i Ukrainy, Wyższej Szkoły Stosunków Międzynarodowych i Komunikacji Społecznej w Chełmie, badaniami dziejów terenów wschodniego pogranicza. Celem prowadzących badania i władz Uczelni jest, by efekty poszukiwań, analiz i naukowych przemyśleń ukazywały się w sukcesywnie wydawanych tomach, częściach, czy zeszytach tworzących całość – jak to określiliśmy w tytule dziejów lubelsko – wołyńskiego pobuża. Podjęta tematyka badań nie jest przypadkowa. Przemawiają za nią potrzeba uzupełnienia luki wydawniczej w tym zakresie, zainteresowania naukowców, a także współpraca z ośrodkami akademickimi Ukrainy, w tym z Narodowym Uniwersytetem Wołyńskim im. Lesi Ukrainki w Łucku oraz z Narodowego Uniwersytetu Lwowskiego im. Iwana Franki we Lwowie. Z dużym zadowoleniem przyjęliśmy fakt, że recenzentami całego cyklu będą: prof. -

Miejscowość Urodzenia Liczba Mieszkańców Lublina LUBLIN 203776 ŚWIDNIK 4621 KRAŚNIK 3005 LUBARTÓW 2861 KRASNYSTAW 2700 BY

Miejscowość urodzenia Liczba mieszkańców Lublina LUBLIN 203776 ŚWIDNIK 4621 KRAŚNIK 3005 LUBARTÓW 2861 KRASNYSTAW 2700 BYCHAWA 2597 PUŁAWY 2335 CHEŁM 2220 BEŁŻYCE 2072 ZAMOŚĆ 1853 WARSZAWA 1778 HRUBIESZÓW 1752 PARCZEW 1645 TOMASZÓW LUBELSKI 1637 JASZCZÓW 1468 RADZYŃ PODLASKI 1139 OPOLE LUBELSKIE 1072 WŁODAWA 1046 BIAŁA PODLASKA 985 PONIATOWA 912 JANÓW LUBELSKI 910 BIŁGORAJ 876 KRZCZONÓW 751 ŁUKÓW 739 SZCZEBRZESZYN 594 RADOM 556 ŻÓŁKIEWKA 547 MICHÓW 523 NAŁĘCZÓW 509 WROCŁAW 500 KOCK 496 KAMIONKA 482 SIEDLISZCZE 448 LONDYN 443 TUROBIN 439 OSTRÓW LUBELSKI 418 RZESZÓW 412 OSTROWIEC ŚWIĘTOKRZYSKI 407 MIĘDZYRZEC PODLASKI 397 KRAKÓW 394 STALOWA WOLA 383 KIJANY 381 SZCZECIN 378 KIELCE 352 RYKI 334 ŁÓDŹ 320 SIEDLCE 317 FRAMPOL 311 BIAŁYSTOK 306 CZEMIERNIKI 306 WISZNICE 300 PRZEMYŚL 297 PIASKI 281 SANDOMIERZ 279 ŁĘCZNA 268 POZNAŃ 264 WYSOKIE 262 GIEŁCZEW 261 GDAŃSK 251 JÓZEFÓW 249 REJOWIEC FABRYCZNY 243 STARA WIEŚ 235 NIEDRZWICA DUŻA 227 CYCÓW 226 KAZIMIERZ DOLNY 216 TARNOGRÓD 212 ADAMÓW 209 DĘBLIN 207 STARACHOWICE 207 MEŁGIEW 206 PIOTRKÓW 202 TARNOBRZEG 198 LWÓW 197 JAROSŁAW 191 NISKO 191 OLSZTYN 185 JABŁONNA 182 PILASZKOWICE 179 RUDNIK 177 JAROSŁAWIEC 172 SKARŻYSKO-KAMIENNA 171 NASUTÓW 170 MASZÓW 167 BYDGOSZCZ 166 KOZIENICE 164 ELBLĄG 159 MOTYCZ 159 JELENIA GÓRA 154 ZAKRZÓWEK 153 GARWOLIN 152 WOHYŃ 150 WAŁBRZYCH 148 ANNOPOL 147 URSZULIN 147 ZAKLIKÓW 145 JASTKÓW 141 WIERZCHOWISKA 141 MIELEC 140 WÓLKA ABRAMOWICKA 140 KATOWICE 139 MIRCZE 139 NIEDRZWICA KOŚCIELNA 139 OPATÓW 138 GARBÓW 137 KOMARÓW-OSADA 137 WILKOŁAZ 137 TARNÓW 136 GRABOWIEC 135 SIEDLISKA