Libya's War Economy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maintenance Condition Monitoring

New trend in lubricants packaging P.20 Consumer choices lubricants survey P.18 WWW.LUBESAFRICA.COM VOL.4 • JULY-SEPTEMBER 2012 NOT FOR SALE MAIN FEATURE Improving plant maintenance through condition monitoring A guide to oil analysis July-September 2012 | LUBEZINE MAGAZINE 1 PLUS: THE MARKET REPORT P.4 Inside Front Cover Full Page Ad 2 LUBEZINE MAGAZINE | July-September 2012 WWW.L UBE S A FR I C A .COM VOL 4 CONTENTS JULY—SEPTEMBER 2012 NEWS • INDUSTRY UPDATE • NEW PRODUCTS • TECHNOLOGY • COMMENTARY MAIN FEATURE 14 | OIL ANALYSIS — THE FUNDAMENTALS INSIDE REGULARS 7 | COUNTRY FEATURE 2 | Editor’s Desk Uganda lubricants market 4 | The Market Report — a brief overview Eac to remove preferential tariff treatment on MAIN FEATURE 10 | lubes produced within Lubrication and condition monitoring Eac block to improve plant availability Motorol Lubricants Open Shop 14 | MAIN FEATURE In Kenya Puma Energy plans buyout of Oil analysis — The Fundamentals KenolKobil 18 | ADVERTISER’S FEATURE Additives exempted from Consumer choices lubricants survey PVoC standards — GFK 6 | Questions from our readers 20 | PACKAGING FEATURE 28 | Last Word Engine oil performance in New trends in lubricants packaging 8 MAINTENANCE numbers 22 | TECHNOLOGY FEATURE FEATURE Oil degradation Turbochargers 26 | PROFILE and lubrication 28 10 questions for lubricants 24 professionals EQUIPMENT 27 | ADVERTISER’S FEATURE FEATURE Lubrication equipment The ultimate solution in sugar mill for a profitable and lubrication professional workshop July-September 2012 | LUBEZINE MAGAZINE 1 Turn to Turbochargers and lubrication P.8 New trend in lubricants packaging P.20 Consumer choices lubricants survey P.18 WWW.LUBESAFRICA.COM VOL.4 • JULY-SEPTEMBER 2012 NOT FOR SALE EDITOR’SDESK VOL 3 • JANUARY-MARCH 2012 MAIN FEATURE Improving plant maintenance through EDITORIAL condition monitoring A guide to oil analysis One year and July-September 2012 | LUBEZINE MAGAZINE 1 PLUS: THE MARKET REPORT P.4 still counting! Publisher: Lubes Africa Ltd elcome to volume four of Lubezine magazine. -

The Impact of Oil Exports on Economic Growth – the Case of Libya

Czech University of Life Sciences Prague Faculty of Economics and Management Department of Economics The Impact of oil Exports on Economic Growth – The Case of Libya Doctoral Thesis Author: Mousbah Ahmouda Supervisor: Doc. Ing. Luboš Smutka, Ph.D. 2014 Abstract The purpose of this thesis is to evaluate and measure the relationship between oil exports and economic growth in Libya by using advancement model and utilize Koyck disseminated lag regression technique (Koyck, 1954; Zvi, 1967) to check the relationship between the oil export of Libya and Libyan GDP using annual data over the period of 1980 to 2013. The research focuses on the impacts of oil exports on the economic growth of Libya. Being a developing country, Libya’s GDP is mainly financed by oil rents and export of hydrocarbons. In addition, the research are applied to test the hypothesis of economic growth strategy led by exports. The research is based on the following hypotheses for testing the causality and co- integration between GDP and oil export in Libya as to whether there is bi-directional causality between GDP growth and export, or whether there is unidirectional causality between the two variables or whether there is no causality between GDP and oil export in Libya. Importantly, this research aims at studying the impact of oil export on the economy. Therefore, the relationship of oil export and economic growth for Libya is a major point. Also the research tried to find out the extent and importance of oil exports on the trade, investment, financing of the budget and the government expenditure. -

Africa 1952-1953

SUMMARY OF RECENT ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS IN AFRICA 1952-53 Supplement to World Economic Report UNITED NATIONS UMMARY OF C T ECONOMIC EVE OPME TS IN AF ICA 1952-53 Supplement World Economic Report UNITED NATIONS DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC AFFAIRS New York, 1954 E/2582 ST/ECA/26 May 1954 UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sal es No.: 1951\..11. C. 3 Price: $U.S. $0.80; 6/- stg.; Sw.fr. 3.00 (or equivalent in other currencies) FOREWDRD This report is issued as a supplement to the World Economic Report, 1952-53, and has been prepared in response to resolution 367 B (XIII) of the Economic and Social Council. It presents a brief analysis of economic trends in Africa, not including Egypt but including the outlying islands in the Indian and Atlantic Oceans, on the basis of currently available statistics of trade, production and development plans covering mainly the year 1952 and the first half of 1953, Thus it carries forward the periodic surveys presented in previous years in accordance with resolution 266 (X) and 367 B (XIII), the most recent being lIRecent trends in trade, production and economic development plansll appearing as part II of lIAspects of Economic Development in Africall issued in April 1953 as a supplement to the World Economic Report, 1951-52, The present report, like the previous ones, was prepared in the Division of Economic Stability and Development of the United Nations Department of Economic Affairs. EXPLANATION OF SYMBOLS The following symbols have been used in the tables throughout the report: Three dots ( ... ) indicate that data -

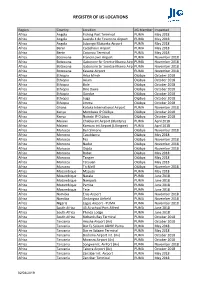

Register of IJS Locations V1.Xlsx

REGISTER OF IJS LOCATIONS Region Country Location JIG Member Inspected Africa Angola Fishing Port Terminal PUMA May 2018 Africa Angola Luanda 4 de Fevereiro Airport PUMA May 2018 Africa Angola Lubango Mukanka Airport PUMA May 2018 Africa Benin Cadjehoun Airport PUMA May 2018 Africa Benin Cotonou Terminal PUMA May 2018 Africa Botswana Francistown Airport PUMA November 2018 Africa Botswana Gaborone Sir Seretse Khama AirpoPUMA November 2018 Africa Botswana Gaborone Sir Seretse Khama AirpoPUMA November 2018 Africa Botswana Kasane Airport PUMA November 2018 Africa Ethiopia Arba Minch OiLibya October 2018 Africa Ethiopia Axum OiLibya October 2018 Africa Ethiopia Bole OiLibya October 2018 Africa Ethiopia Dire Dawa OiLibya October 2018 Africa Ethiopia Gondar OiLibya October 2018 Africa Ethiopia Jijiga OiLibya October 2018 Africa Ethiopia Jimma OiLibya October 2018 Africa Ghana Kotoka International Airport PUMA November 2018 Africa Kenya Mombasa IP OiLibya OiLibya October 2018 Africa Kenya Nairobi IP OiLibya OiLibya October 2018 Africa Malawi Chileka Int Airport (Blantyre) PUMA April 2018 Africa Malawi Kamuzu int.Airport (Lilongwe) PUMA April 2018 Africa Morocco Ben Slimane OiLibya November 2018 Africa Morocco Casablanca OiLibya May 2018 Africa Morocco Fez OiLibya November 2018 Africa Morocco Nador OiLibya November 2018 Africa Morocco Oujda OiLibya November 2018 Africa Morocco Rabat OiLibya May 2018 Africa Morocco Tangier OiLibya May 2018 Africa Morocco Tetouan OiLibya May 2018 Africa Morocco Tit Melil OiLibya November 2018 Africa Mozambique Maputo -

Libyan Municipal Council Research 1

Libyan Municipal Council Research 1. Detailed Methodology 2. Participation 3. Awareness 4. Knowledge 5. Communication 6. Service Delivery 7. Legitimacy 8. Drivers of Legitimacy 9. Focus Group Recommendations 10. Demographics Detailed Methodology • The survey was conducted on behalf of the International Republican Institute’s Center for Insights in Survey Research by Altai Consulting. This research is intended to support the development and evaluation of IRI and USAID/OTI Libya Transition Initiative programming with municipal councils. The research consisted of quantitative and qualitative components, conducted by IRI and USAID/OTI Libya Transition Initiative respectively. • Data was collected April 14 to May 24, 2016, and was conducted over the phone from Altai’s call center using computer-assisted telephone technology. • The sample was 2,671 Libyans aged 18 and over. • Quantitative: Libyans from the 22 administrative districts were interviewed on a 45-question questionnaire on municipal councils. In addition, 13 municipalities were oversampled to provide a more focused analysis on municipalities targeted by programming. Oversampled municipalities include: Tripoli Center (224), Souq al Jumaa (229), Tajoura (232), Abu Salim (232), Misrata (157), Sabratha (153), Benghazi (150), Bayda (101), Sabha (152), Ubari (102), Weddan (101), Gharyan (100) and Shahat (103). • The sample was post-weighted in order to ensure that each district corresponds to the latest population pyramid available on Libya (US Census Bureau Data, updated 2016) in order for the sample to be nationally representative. • Qualitative: 18 focus groups were conducted with 5-10 people of mixed employment status and level of education in Tripoli Center (men and women), Souq al Jumaa (men and women), Tajoura (men), Abu Salim (men), Misrata (men and women), Sabratha (men and women), Benghazi (men and women), Bayda (men), Sabha (men and women), Ubari (men), and Shahat (men). -

Libya: Conflict, Transition, and U.S

Libya: Conflict, Transition, and U.S. Policy Updated April 13, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL33142 SUMMARY RL33142 Libya: Conflict, Transition, and U.S. Policy April 13, 2020 Libya’s political transition has been disrupted by armed non-state groups and threatened by the indecision and infighting of interim leaders. After a uprising ended the 40-plus-year rule of Christopher M. Blanchard Muammar al Qadhafi in 2011, interim authorities proved unable to form a stable government, Specialist in Middle address security issues, reshape the country’s finances, or create a viable framework for post- Eastern Affairs conflict justice and reconciliation. Insecurity spread as local armed groups competed for influence and resources. Qadhafi compounded stabilization challenges by depriving Libyans of experience in self-government, stifling civil society, and leaving state institutions weak. Militias, local leaders, and coalitions of national figures with competing foreign patrons remain the most powerful arbiters of public affairs. An atmosphere of persistent lawlessness has enabled militias, criminals, and Islamist terrorist groups to operate with impunity, while recurrent conflict has endangered civilians’ rights and safety. Issues of dispute have included governance, military command, national finances, and control of oil infrastructure. Key Issues and Actors in Libya. After a previous round of conflict in 2014, the country’s transitional institutions fragmented. A Government of National Accord (GNA) based in the capital, Tripoli, took power under the 2015 U.N.- brokered Libyan Political Agreement. Leaders of the House of Representatives (HOR) that were elected in 2014 declined to endorse the GNA, and they and a rival interim government based in eastern Libya have challenged the GNA’s authority with support from the Libyan National Army/Libyan Arab Armed Forces (LNA/LAAF) movement. -

LONCHENA-THESIS-2020.Pdf

FAILED STATES: DEFINING WHAT A FAILED STATES IS AND WHY NOT ALL FAILED STATES AFFECT UNITED STATES NATIONAL SECURITY by Timothy Andrew Lonchena A thesis submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Global Security Studies Baltimore, Maryland May 2020 2020 Timothy Lonchena All rights reserved Abstract: Failed States have been discussed for over the past twenty years since the terrorist attacks of the United States on September 11th, 2001. The American public became even more familiar with the term “failed states” during the Arab Spring movement when several countries in the Middle East and North Africa underwent regime changes. The result of these regime changes was a more violent group of terrorists, such as the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL). This thesis will address how to define failed states to ensure there is an understood baseline when looking to determine if a state could possibly fail. Further, this thesis will examine the on-going debate addressing the question of those who claim failed states can’t be predicted and determine if analytic modeling can be applied to the identification of failed states. The thesis also examines the need to identify “failed states” before they fail and will also discuss the effects certain failed states have directly on United States national security. Given this, the last portion of this paper and argument to be addressed will determine if there are certain failing states that the United States will not provide assistance to, as it is not in the best interest of our national security and that of our allies. -

Cameroon's Finance Sector Goes Through Rapid Digitalization

MAJOR PROJECTS AGRICULTURE ENERGY BUSINESS IN MINING INDUSTRY SERVICES FINANCE November 2018 / N° 69 November 2018 CAMEROON Cameroon’s finance sector goes through rapid digitalization Cashew, a sector with great Oilibya rebranded, becomes potential, both for revenues Ola Energy and job creation FREE - CANNOT BE SOLD BUSINESSIN CAMEROON .COM Daily business news from Cameroon Compatible with iPads, smartphones or tablets APP AVAILABLE ON IOS AND ANDROID 3 Yasmine Bahri-Domon Cameroon goes through digital transformation Digitalization is spreading more and human resources will be necessary more to many sectors in Cameroon. to overcome issues arising from this It has become vital for any business modernization. The latter must align wishing to get closer to its customers with social fabric and structure. I and actually is the perfect tool for client believe that the transformation must retention. This is the exact case in other be gradual but also take into account African nations where digitalization direct employment, or this might lead is a boost palliating shortcomings in to an imbalance that will affect social quality of service provided. economy. Cameroon’s technology is going As said earlier, fact remains that digi- through a transformation as various talization helps financial institutions sectors indeed migrate toward digital- process their transaction and serve ization. This silent transformation is clients more rapidly. gradually taking shape and imposing There are “Made in Cameroon” apps itself to various targets. It is positive that currently let users conduct finan- evolution and it has today become a cial transactions or operations safely, must for financial institutions. It ap- using mobile devices such as phones or pears that customers have adapted to tablets. -

For Ubari LBY2007 Libya

Research Terms of Reference Area-Based Assessment (ABA) for Ubari LBY2007 Libya 22nd of January, 2021 V3 1. Executive Summary Country of intervention Libya Type of Emergency □ Natural disaster X Conflict Type of Crisis □ Sudden onset □ Slow onset X Protracted Mandating Body/ EUTF Agency Project Code 14EHG Overall Research Timeframe (from 01/10/2020 to 14/04/2021 research design to final outputs / M&E) Research Timeframe 1. Start collect data: 26/01/2021 5. Preliminary presentation: 13/03/2021 Add planned deadlines 2. Data collected: 25/02/2021 6. Outputs sent for validation: 31/03/2021 (for first cycle if more 3. Data analysed: 05/03/2021 7. Outputs published: 14/04/2021 than 1) 4. Data sent for validation: 31/03/2021 8. Final presentation: 14/04/2021 Number of X Single assessment (one cycle) assessments □ Multi assessment (more than one cycle) [Describe here the frequency of the cycle] Humanitarian Milestone Deadline milestones □ Donor plan/strategy _ _/_ _/_ _ _ _ Specify what will the □ Inter-cluster plan/strategy _ _/_ _/_ _ _ _ assessment inform and □ Cluster plan/strategy _ _/_ _/_ _ _ _ when e.g. The shelter cluster □ NGO platform plan/strategy _ _/_ _/_ _ _ _ will use this data to X Other (Specify): 31/03/2021 The Area-Based Assessment draft its Revised Flash (ABA) for Ubari will directly inform ACTED Appeal; protection activities in Ubari. (See rationale) Audience Type & Audience type Dissemination Dissemination Specify X Strategic X General Product Mailing (e.g. -

Libya the Politics of Power, Protection, Identity and Illicit Trade

United Nations University Centre for Policy Research Crime-Conflict Nexus Series: No 3 May 2017 Libya The Politics of Power, Protection, Identity and Illicit Trade Tuesday Reitano Deputy Director, Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime Mark Shaw Director, Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime This material has been funded by UK aid from the UK government; however the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies. © 2017 United Nations University. All Rights Reserved. ISBN 978-92-808-9044-0 Libya The Politics of Power, Protection, Identity and Illicit Trade 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Post-Revolution Libya has fractured into a volatile plethora of political ecosystems and protection economies, in which access to resources has become critical to survival. The struggle for control over illicit flows has shaped Libya’s civil conflict and remains a decisive centrifugal force, actively preventing central state consolidation. Illicit flows exposed the deep fissures within Libyan society, divisions that the Gaddafi regime had controlled through a combination of force and the manipulation of economic interests in both the legitimate and illicit economy. The impact of illicit flows, however, has been different in different parts of the country: in a perverse resource triangle, coastal groups, while linked to the illicit economy (particularly through the control of ports and airports), have been paid by the state, while also relying on external financial support in a proxy war between competing interests centered in the Gulf. In the southern borderlands of the country, by contrast, control of trafficking, and the capture of the country’s oil resources, have been key drivers in strengthening conflict protagonists. -

The Human Conveyor Belt : Trends in Human Trafficking and Smuggling in Post-Revolution Libya

The Human Conveyor Belt : trends in human trafficking and smuggling in post-revolution Libya March 2017 A NETWORK TO COUNTER NETWORKS The Human Conveyor Belt : trends in human trafficking and smuggling in post-revolution Libya Mark Micallef March 2017 Cover image: © Robert Young Pelton © 2017 Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Global Initiative. Please direct inquiries to: The Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime WMO Building, 2nd Floor 7bis, Avenue de la Paix CH-1211 Geneva 1 Switzerland www.GlobalInitiative.net Acknowledgments This report was authored by Mark Micallef for the Global Initiative, edited by Tuesday Reitano and Laura Adal. Graphics and layout were prepared by Sharon Wilson at Emerge Creative. Editorial support was provided by Iris Oustinoff. Both the monitoring and the fieldwork supporting this document would not have been possible without a group of Libyan collaborators who we cannot name for their security, but to whom we would like to offer the most profound thanks. The author is also thankful for comments and feedback from MENA researcher Jalal Harchaoui. The research for this report was carried out in collaboration with Migrant Report and made possible with funding provided by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Norway, and benefitted from synergies with projects undertaken by the Global Initiative in partnership with the Institute for Security Studies and the Hanns Seidel Foundation, the United Nations University, and the UK Department for International Development. About the Author Mark Micallef is an investigative journalist and researcher specialised on human smuggling and trafficking. -

International Medical Corps in Libya from the Rise of the Arab Spring to the Fall of the Gaddafi Regime

International Medical Corps in Libya From the rise of the Arab Spring to the fall of the Gaddafi regime 1 International Medical Corps in Libya From the rise of the Arab Spring to the fall of the Gaddafi regime Report Contents International Medical Corps in Libya Summary…………………………………………… page 3 Eight Months of Crisis in Libya…………………….………………………………………… page 4 Map of International Medical Corps’ Response.…………….……………………………. page 5 Timeline of Major Events in Libya & International Medical Corps’ Response………. page 6 Eastern Libya………………………………………………………………………………....... page 8 Misurata and Surrounding Areas…………………….……………………………………… page 12 Tunisian/Libyan Border………………………………………………………………………. page 15 Western Libya………………………………………………………………………………….. page 17 Sirte, Bani Walid & Sabha……………………………………………………………………. page 20 Future Response Efforts: From Relief to Self-Reliance…………………………………. page 21 International Medical Corps Mission: From Relief to Self-Reliance…………………… page 24 International Medical Corps in the Middle East…………………………………………… page 24 International Medical Corps Globally………………………………………………………. Page 25 Operational data contained in this report has been provided by International Medical Corps’ field teams in Libya and Tunisia and is current as of August 26, 2011 unless otherwise stated. 2 3 Eight Months of Crisis in Libya Following civilian demonstrations in Tunisia and Egypt, the people of Libya started to push for regime change in mid-February. It began with protests against the leadership of Colonel Muammar al- Gaddafi, with the Libyan leader responding by ordering his troops and supporters to crush the uprising in a televised speech, which escalated the country into armed conflict. The unrest began in the eastern Libyan city of Benghazi, with the eastern Cyrenaica region in opposition control by February 23 and opposition supporters forming the Interim National Transitional Council on February 27.