Challenging the Assumptions of the Libyan Conflict

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Haftar's Calculus for Libya: What Happened, and What Is Next? ICSR Insight by Inga Kristina Trauthig

Haftar's Calculus for Libya: What Happened, and What is Next? ICSR Insight by Inga Kristina Trauthig In recent days, a battle for Tripoli has At the time of writing, fighting is been raging that bears the forlorn ongoing. On Sunday, 8 April, Tripoli’s possibility of regression for Libya as a only functioning civilian airport at Mitiga whole. A military offensive led by was forced to be evacuated as it was General Khalifa Haftar, commander of hit with air strikes attributed to the LNA. the so-called “Libyan National Army” These airstrikes took place the same (LNA) that mostly controls eastern day that the “Tripoli International Fair” Libya, was launched on April 3, to the occurred, signalling the formidable level dismay of much the international of resilience Libyans have attained after community. A few days after the launch eight years of turbulence following of the military campaign by Haftar, Qaddafi’s overthrow. some analysts have already concluded that “Libya is (…) [in] its third civil war since 2011”. The LNA forces first took the town of Gharyan, 100 km south of Tripoli, before advancing to the city’s outskirts. ICSR, Department of War Studies, King’s College London. All rights reserved. Haftar's Calculus for Libya: What Happened, and What is Next? ICSR Insight by Inga Kristina Trauthig What is happening? Haftar had been building his forces in central Libya for months. At the beginning of the year, he claimed to have “taken control” of southern Libya, indicating that he was prepping for an advance on the western part of Libya, the last piece missing. -

The Crisis in Libya

APRIL 2011 ISSUE BRIEF # 28 THE CRISIS IN LIBYA Ajish P Joy Introduction Libya, in the throes of a civil war, now represents the ugly facet of the much-hyped Arab Spring. The country, located in North Africa, shares its borders with the two leading Arab-Spring states, Egypt and Tunisia, along with Sudan, Tunisia, Chad, Niger and Algeria. It is also not too far from Europe. Italy lies to its north just across the Mediterranean. With an area of 1.8 million sq km, Libya is the fourth largest country in Africa, yet its population is only about 6.4 million, one of the lowest in the continent. Libya has nearly 42 billion barrels of oil in proven reserves, the ninth largest in the world. With a reasonably good per capita income of $14000, Libya also has the highest HDI (Human Development Index) in the African continent. However, Libya’s unemployment rate is high at 30 percent, taking some sheen off its economic credentials. Libya, a Roman colony for several centuries, was conquered by the Arab forces in AD 647 during the Caliphate of Utman bin Affan. Following this, Libya was ruled by the Abbasids and the Shite Fatimids till the Ottoman Empire asserted its control in 1551. Ottoman rule lasted for nearly four centuries ending with the Ottoman defeat in the Italian-Ottoman war. Consequently, Italy assumed control of Libya under the Treaty of 1 Lausanne (1912). The Italians ruled till their defeat in the Second World War. The Libyan constitution was enacted in 1949 and two years later under Mohammed Idris (who declared himself as Libya’s first King), Libya became an independent state. -

Medical Conditions in the Western Desert and Tobruk

CHAPTER 1 1 MEDICAL CONDITIONS IN THE WESTERN DESERT AND TOBRU K ON S I D E R A T I O N of the medical and surgical conditions encountered C by Australian forces in the campaign of 1940-1941 in the Wester n Desert and during the siege of Tobruk embraces the various diseases me t and the nature of surgical work performed . In addition it must includ e some assessment of the general health of the men, which does not mean merely the absence of demonstrable disease . Matters relating to organisa- tion are more appropriately dealt with in a later chapter in which the lessons of the experiences in the Middle East are examined . As told in Chapter 7, the forward surgical work was done in a main dressing statio n during the battles of Bardia and Tobruk . It is admitted that a serious difficulty of this arrangement was that men had to be held for some tim e in the M.D.S., which put a brake on the movements of the field ambulance , especially as only the most severely wounded men were operated on i n the M.D.S. as a rule, the others being sent to a casualty clearing statio n at least 150 miles away . Dispersal of the tents multiplied the work of the staff considerably. SURGICAL CONDITIONS IN THE DESER T Though battle casualties were not numerous, the value of being able to deal with varied types of wounds was apparent . In the Bardia and Tobruk actions abdominal wounds were few. Major J. -

WESTERN DESERT CAMPAIGN Sept-Nov1940 Begin Between the 10Th and 15Th October and to Be Concluded by Th E End of the Month

CHAPTER 7 WESTERN DESERT CAMPAIG N HEN, during the Anglo-Egyptian treaty negotiations in 1929, M r W Bruce as Prime Minister of Australia emphasised that no treat y would be acceptable to the Commonwealth unless it adequately safeguarded the Suez Canal, he expressed that realisation of the significance of sea communications which informed Australian thoughts on defence . That significance lay in the fact that all oceans are but connected parts o f a world sea on which effective action by allies against a common enem y could only be achieved by a common strategy . It was as a result of a common strategy that in 1940 Australia ' s local naval defence was denude d to reinforce offensive strength at a more vital point, the Suez Canal an d its approaches. l No such common strategy existed between the Germans and the Italians, nor even between the respective dictators and thei r commanders-in-chief . Instead of regarding the sea as one and indivisible , the Italians insisted that the Mediterranean was exclusively an Italia n sphere, a conception which was at first endorsed by Hitler . The shelvin g of the plans for the invasion of England in the autumn of 1940 turne d Hitler' s thoughts to the complete subjugation of Europe as a preliminary to England ' s defeat. He became obsessed with the necessity to attack and conquer Russia . In viewing the Mediterranean in relation to German action he looked mainly to the west, to the entry of Spain into the war and th e capture of Gibraltar as part of the European defence plan . -

Libyan Municipal Council Research 1

Libyan Municipal Council Research 1. Detailed Methodology 2. Participation 3. Awareness 4. Knowledge 5. Communication 6. Service Delivery 7. Legitimacy 8. Drivers of Legitimacy 9. Focus Group Recommendations 10. Demographics Detailed Methodology • The survey was conducted on behalf of the International Republican Institute’s Center for Insights in Survey Research by Altai Consulting. This research is intended to support the development and evaluation of IRI and USAID/OTI Libya Transition Initiative programming with municipal councils. The research consisted of quantitative and qualitative components, conducted by IRI and USAID/OTI Libya Transition Initiative respectively. • Data was collected April 14 to May 24, 2016, and was conducted over the phone from Altai’s call center using computer-assisted telephone technology. • The sample was 2,671 Libyans aged 18 and over. • Quantitative: Libyans from the 22 administrative districts were interviewed on a 45-question questionnaire on municipal councils. In addition, 13 municipalities were oversampled to provide a more focused analysis on municipalities targeted by programming. Oversampled municipalities include: Tripoli Center (224), Souq al Jumaa (229), Tajoura (232), Abu Salim (232), Misrata (157), Sabratha (153), Benghazi (150), Bayda (101), Sabha (152), Ubari (102), Weddan (101), Gharyan (100) and Shahat (103). • The sample was post-weighted in order to ensure that each district corresponds to the latest population pyramid available on Libya (US Census Bureau Data, updated 2016) in order for the sample to be nationally representative. • Qualitative: 18 focus groups were conducted with 5-10 people of mixed employment status and level of education in Tripoli Center (men and women), Souq al Jumaa (men and women), Tajoura (men), Abu Salim (men), Misrata (men and women), Sabratha (men and women), Benghazi (men and women), Bayda (men), Sabha (men and women), Ubari (men), and Shahat (men). -

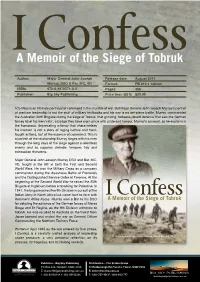

A Memoir of the Siege of Tobruk

I Confess A Memoir of the Siege of Tobruk Author: Major General John Joseph Release date: August 2011 Murray, DSO & Bar, MC, VD Format: PB 210 x 148mm ISBN: 978-0-9870574-8-8 Pages: 256 Publisher: Big Sky Publishing Price (incl. GST): $29.99 I Confess is an intimate portrayal of command in the crucible of war. But Major General John Joseph Murray’s portrait of wartime leadership is not the stuff of military textbooks and his war is no set-piece battle. Murray commanded the Australian 20th Brigade during the siege of Tobruk, that grinding, tortuous desert defence that saw the German forces label his men ‘rats’, a badge they have worn since with pride and honour. Murray’s account, as he explains in the humorous, deprecating whimsy that characterises his memoir, is not a story of raging battles and hard- fought actions, but of the essence of command. This is a portrait of the relationship Murray forges with his men through the long days of the siege against a relentless enemy and as supplies dwindle, tempers fray and exhaustion threatens. Major General John Joseph Murray DSO and Bar, MC, VD, fought in the AIF in both the First and Second World Wars. He won the Military Cross as a company commander during the disastrous Battle of Fromelles and the Distinguished Service Order at Peronne. At the beginning of the Second World War he raised the 20th Brigade at Ingleburn before embarking for Palestine. In 1941, the brigade joined the 9th Division in pursuit of the Italian Army in North Africa but came face to face with Rommel’s Afrika Korps. -

Libya's Conflict

LIBYA’S BRIEF / 12 CONFLICT Nov 2019 A very short introduction SERIES by Wolfgang Pusztai Freelance security and policy analyst * INTRODUCTION Eight years after the revolution, Libya is in the mid- dle of a civil war. For more than four years, inter- national conflict resolution efforts have centred on the UN-sponsored Libya Political Agreement (LPA) process,1 unfortunately without achieving any break- through. In fact, the situation has even deteriorated Summary since the onset of Marshal Haftar’s attack on Tripoli on 4 April 2019.2 › Libya is a failed state in the middle of a civil war and increasingly poses a threat to the An unstable Libya has wide-ranging impacts: as a safe whole region. haven for terrorists, it endangers its north African neighbours, as well as the wider Sahara region. But ter- › The UN-facilitated stabilisation process was rorists originating from or trained in Libya are also a unsuccessful because it ignored key political threat to Europe, also through the radicalisation of the actors and conflict aspects on the ground. Libyan expatriate community (such as the Manchester › While partially responsible, international Arena bombing in 2017).3 Furthermore, it is one of the interference cannot be entirely blamed for most important transit countries for migrants on their this failure. way to Europe. Through its vast oil wealth, Libya is also of significant economic relevance for its neigh- › Stabilisation efforts should follow a decen- bours and several European countries. tralised process based on the country’s for- mer constitution. This Conflict Series Brief focuses on the driving factors › Wherever there is a basic level of stability, of conflict dynamics in Libya and on the shortcomings fostering local security (including the crea- of the LPA in addressing them. -

Gaddafi Supporters Since 2011

Country Policy and Information Note Libya: Actual or perceived supporters of former President Gaddafi Version 3.0 April 2019 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the basis of claim section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme. It is split into two main sections: (1) analysis and assessment of COI and other evidence; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below. Assessment This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note – i.e. the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw – by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment on whether, in general: • A person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm • A person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies) • A person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory • Claims are likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and • If a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. Decision makers must, however, still consider all claims on an individual basis, taking into account each case’s specific facts. Country of origin information The country information in this note has been carefully selected in accordance with the general principles of COI research as set out in the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI), dated April 2008, and the Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation’s (ACCORD), Researching Country Origin Information – Training Manual, 2013. -

After Gaddafi 01 0 0.Pdf

Benghazi in an individual capacity and the group it- ures such as Zahi Mogherbi and Amal al-Obeidi. They self does not seem to be reforming. Al-Qaeda in the found an echo in the administrative elites, which, al- Islamic Maghreb has also been cited as a potential though they may have served the regime for years, spoiler in Libya. In fact, an early attempt to infiltrate did not necessarily accept its values or projects. Both the country was foiled and since then the group has groups represent an essential resource for the future, been taking arms and weapons out of Libya instead. and will certainly take part in a future government. It is unlikely to play any role at all. Scenarios for the future The position of the Union of Free Officers is unknown and, although they may form a pressure group, their membership is elderly and many of them – such as the Three scenarios have been proposed for Libya in the rijal al-khima (‘the men of the tent’ – Colonel Gaddafi’s future: (1) the Gaddafi regime is restored to power; closest confidants) – too compromised by their as- (2) Libya becomes a failing state; and (3) some kind sociation with the Gaddafi regime. The exiled groups of pluralistic government emerges in a reunified state. will undoubtedly seek roles in any new regime but The possibility that Libya remains, as at present, a they suffer from the fact that they have been abroad divided state between East and West has been ex- for up to thirty years or more. -

Libya Conflict Insight | Feb 2018 | Vol

ABOUT THE REPORT The purpose of this report is to provide analysis and Libya Conflict recommendations to assist the African Union (AU), Regional Economic Communities (RECs), Member States and Development Partners in decision making and in the implementation of peace and security- related instruments. Insight CONTRIBUTORS Dr. Mesfin Gebremichael (Editor in Chief) Mr. Alagaw Ababu Kifle Ms. Alem Kidane Mr. Hervé Wendyam Ms. Mahlet Fitiwi Ms. Zaharau S. Shariff Situation analysis EDITING, DESIGN & LAYOUT Libya achieved independence from United Nations (UN) trusteeship in 1951 Michelle Mendi Muita (Editor) as an amalgamation of three former Ottoman provinces, Tripolitania, Mikias Yitbarek (Design & Layout) Cyrenaica and Fezzan under the rule of King Mohammed Idris. In 1969, King Idris was deposed in a coup staged by Colonel Muammar Gaddafi. He promptly abolished the monarchy, revoked the constitution, and © 2018 Institute for Peace and Security Studies, established the Libya Arab Republic. By 1977, the Republic was transformed Addis Ababa University. All rights reserved. into the leftist-leaning Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya. In the 1970s and 1980s, Libya pursued a “deviant foreign policy”, epitomized February 2018 | Vol. 1 by its radical belligerence towards the West and its endorsement of anti- imperialism. In the late 1990s, Libya began to re-normalize its relations with the West, a development that gradually led to its rehabilitation from the CONTENTS status of a pariah, or a “rogue state.” As part of its rapprochement with the Situation analysis 1 West, Libya abandoned its nuclear weapons programme in 2003, resulting Causes of the conflict 2 in the lifting of UN sanctions. -

Libya Country Report Matteo Capasso, Jędrzej Czerep, Andrea Dessì, Gabriella Sanchez

Libya Country Report Matteo Capasso, Jędrzej Czerep, Andrea Dessì, Gabriella Sanchez This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 769886 DOCUMENT INFORMATION Project Project acronym: EU-LISTCO Project full title: Europe’s External Action and the Dual Challenges of Limited Statehood and Contested Order Grant agreement no.: 769886 Funding scheme: H2020 Project start date: 01/03/2018 Project duration: 36 months Call topic: ENG-GLOBALLY-02-2017 Shifting global geopolitics and Europe’s preparedness for managing risks, mitigation actions and fostering peace Project website: https://www.eu-listco.net/ Document Deliverable number: XX Deliverable title: Libya: A Country Report Due date of deliverable: XX Actual submission date: XXX Editors: XXX Authors: Matteo Capasso, Jędrzej Czerep, Andrea Dessì, Gabriella Sanchez Reviewers: XXX Participating beneficiaries: XXX Work Package no.: WP4 Work Package title: Risks and Threats in Areas of Limited Statehood and Contested Order in the EU’s Eastern and Southern Surroundings Work Package leader: EUI Work Package participants: FUB, PSR, Bilkent, CIDOB, EUI, Sciences Po, GIP, IDC, IAI, PISM, UIPP, CED Dissemination level: Public Nature: Report Version: 1 Draft/Final: Final No of pages (including cover): 38 2 “More than ever, Libyans are now fighting the wars of other countries, which appear content to fight to the last Libyan and to see the country entirely destroyed in order to settle their own scores”1 1. INTRODUCTION This study on Libya is one of a series of reports prepared within the framework of the EU- LISTCO project, funded under the EU’s Horizon 2020 programme. -

Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 30 / Tuesday, February 14, 1995 / Rules and Regulations

8300 Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 30 / Tuesday, February 14, 1995 / Rules and Regulations § 300.1 Installment agreement fee. Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20220. Determinations that persons fall (a) Applicability. This section applies The full list of persons blocked pursuant within the definition of the term to installment agreements under section to economic sanctions programs ``Government of Libya'' and are thus 6159 of the Internal Revenue Code. administered by the Office of Foreign Specially Designated Nationals of Libya (b) Fee. The fee for entering into an Assets Control is available electronically are effective upon the date of installment agreement is $43. on The Federal Bulletin Board (see determination by the Director of FAC, (c) Person liable for fee. The person SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION). acting under the authority delegated by liable for the installment agreement fee FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: J. the Secretary of the Treasury. Public is the taxpayer entering into an Robert McBrien, Chief, International notice is effective upon the date of installment agreement. Programs Division, Office of Foreign publication or upon actual notice, Assets Control, tel.: 202/622±2420. whichever is sooner. § 300.2 Restructuring or reinstatement of The list of Specially Designated installment agreement fee. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: Nationals in appendices A and B is a (a) Applicability. This section applies Electronic Availability partial one, since FAC may not be aware to installment agreements under section of all agencies and officers of the 6159 of the Internal Revenue Code that This document is available as an Government of Libya, or of all persons are in default. An installment agreement electronic file on The Federal Bulletin that might be owned or controlled by, or is deemed to be in default when a Board the day of publication in the acting on behalf of the Government of taxpayer fails to meet any of the Federal Register.