Agriculture and Rural Livelihoods Needs Assessment – Libya 1 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Llilll,,Ll Lilllll L Lllll'lll Ll Llllllllllll O

llilll,,ll lilllll l lllll'lll ll llllllllllll o E: inf [email protected] w.abbeybookbinding.co.uk t 1'.a. PRIFYSGOL CYMRU THE UNIVERSITY OF WALES WORKFORCE ANALYSIS FOR THE LIBYAN HOTEL SECTOR: STAKEHOLDER PERSPECTIVES AHMED ALI ABDALLA NAAMA, BSC., MSC. Thesis submitted to the Cardiff School of Management in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. 2007 Cardiff School of Management, University of Wales Institute, Cardiff' Colchester Avenue, CARDIFF, CF23 9XR United Kingdom l_l\Nlic Declaration DECLARATION I declare that this work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted for any other degree. I further declare that this thesis is the result of my own independent work and investigation, except where otherwise stated (a bibliography is appended). Finally, I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for interJibrary loan, and for the title and abstract to be made available to outside organisations. Ahmed Ali Abdalla Naama (Candidate) Dr. Claire Haven-Tang (Director of S ) ones (Supervisor) Acknowledqements ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Praise be to Allah; the Cherisher and Sustainer of the worlds; most Gracious, most Merciful. He has given me the ability to do this work. This thesis would not have been possible without the guidance, information and support provided by many people. In particular, I would like to thank my Director of Studies, Dr. Claire Haven-Tang and my supervisor, Professor Eleri Jones for their continuing support, valuable input during the work, patience and undoubted knowledge and wisdom. -

Libyan Municipal Council Research 1

Libyan Municipal Council Research 1. Detailed Methodology 2. Participation 3. Awareness 4. Knowledge 5. Communication 6. Service Delivery 7. Legitimacy 8. Drivers of Legitimacy 9. Focus Group Recommendations 10. Demographics Detailed Methodology • The survey was conducted on behalf of the International Republican Institute’s Center for Insights in Survey Research by Altai Consulting. This research is intended to support the development and evaluation of IRI and USAID/OTI Libya Transition Initiative programming with municipal councils. The research consisted of quantitative and qualitative components, conducted by IRI and USAID/OTI Libya Transition Initiative respectively. • Data was collected April 14 to May 24, 2016, and was conducted over the phone from Altai’s call center using computer-assisted telephone technology. • The sample was 2,671 Libyans aged 18 and over. • Quantitative: Libyans from the 22 administrative districts were interviewed on a 45-question questionnaire on municipal councils. In addition, 13 municipalities were oversampled to provide a more focused analysis on municipalities targeted by programming. Oversampled municipalities include: Tripoli Center (224), Souq al Jumaa (229), Tajoura (232), Abu Salim (232), Misrata (157), Sabratha (153), Benghazi (150), Bayda (101), Sabha (152), Ubari (102), Weddan (101), Gharyan (100) and Shahat (103). • The sample was post-weighted in order to ensure that each district corresponds to the latest population pyramid available on Libya (US Census Bureau Data, updated 2016) in order for the sample to be nationally representative. • Qualitative: 18 focus groups were conducted with 5-10 people of mixed employment status and level of education in Tripoli Center (men and women), Souq al Jumaa (men and women), Tajoura (men), Abu Salim (men), Misrata (men and women), Sabratha (men and women), Benghazi (men and women), Bayda (men), Sabha (men and women), Ubari (men), and Shahat (men). -

1. the Big Picture Political Security

Libya Weekly Political Security Update Bell Whispering Bell March 17, 2020 1. The Big Picture Oil crisis to take centre stage amid COVID-19 concerns While ,fighting remains limited to bouts of violence More importantly, the LNA is expected to exploit the and intermittent skirmishes between Libyan situation to strengthen its case for accessing oil & National Army (LNA) and Government of National gas revenues. Of note, the blockade on exports Accord (GNA) forces, reinforcements continue to orchestrated by pro-LNA tribes continues to deepen underline the prospect of an escalation in Libya’s with losses now estimated at 3 billion USD west, especially along the Sirte-Weshka-Abugrein according to the National Oil Corporation (NOC). engagement axes. Reports of large GNA-aligned The oil crisis was the centre of Haftar’s Paris and CONTENTS Misrata military reinforcements were spotted Berlin visits. France’s diplomacy made it clear this arriving in Abugrein to join the GNA’s Sirte-Jufra week that Haftar forms an integral part of Libya’s Ops Room on 09 March. In response, the LNA’s future. Haftar met with French President Emmanuel 1 general command mobilised additional resources Macron and expressed commitment to abide by a THE BIG PICTURE towards Weshka - Abugrein on 10 March. ceasefire if GNA forces comply. Haftar’s Paris visit Oil crisis to take centre stage was low-profile and no official communique was amid COVID-19 concerns The LNA led by Khalifa Haftar continues to claim it released, leading French media to underline the is monitoring GNA preparations for a broader Elysee’s low confidence in a resolution. -

Líbia Egységét

Besenyő János – Marsai Viktor Országismertető L Í B I A - 2012 - AZ MH ÖSSZHADERŐNEMI PARANCSNOKSÁG TUDOMÁNYOS TANÁCS KIADVÁNYA Felelős kiadó: Domján László vezérőrnagy az MH Összhaderőnemi Parancsnokság parancsnoka Szerkesztő: Dr. Földesi Ferenc Szakmai lektor: N. Rózsa Erzsébet és Szilágyi Péter Postacím: 8000 Székesfehérvár, Zámolyi út 2-6 8001. Pf 151 Telefon: 22-542811 Fax: 22-542836 E-mail: [email protected] ISBN 978-963-89037-5-4 Nyomdai előkészítés, nyomás: OOK-Press Kft, Veszprém Pápai út 37/A Felelős vezető: Szathmáry Attila Minden jog fenntartva ELŐSZÓ 2011 februárjában az addig Észak-Afrika egyik legstabilabb államának tartott Líbiában pol- gárháború tört ki a 42 éve hatalmon levő diktátor és a megbuktatására törő felkelői csoportok között. Nyolc hónapos harcok után – a NATO intenzív légicsapásainak is köszönhetően – Muammar al-Kaddáfi elnök rendszere megbukott, a vezér elesett a Szirt körüli harcokban, a Nemzeti Átmeneti Tanács pedig bejelentette az ország felszabadulását. A polgárháború azon- ban nem múlt el nyomtalanul a társadalomban, és olyan korábbi ellentéteket szított fel az ország régiói és törzsei között, amelyek veszélyeztethetik a stabilitást és Líbia egységét. Hazánk élénk fi gyelemmel követte nyomon a líbiai eseményeket. Az Európai Unió Tanácsának soros elnökeként a tripoli magyar nagykövetség képviselte az EU-t az országban, hazánk aktiválta a Polgári Védelmi Mechanizmust, illetve segített az EU-s és harmadik országokba tartozó állam- polgárok repatriálásában. Bár Orbán Viktor miniszterelnök és Martonyi János külügyminiszter hangsúlyozta, hogy hazánk nem szándékozik részt vállalni a harci cselekményekben, késznek mu- tatkozott egy orvoscsoport bevetésére, amelyre végül nem került sor.1 Az események eszkaláló- dása után az EUFOR LIBYA műveletbe azonban két orvos tisztet delegált a Magyar Honvédség.2 Líbia azonban e sorok írásakor (2012. -

The Human Conveyor Belt : Trends in Human Trafficking and Smuggling in Post-Revolution Libya

The Human Conveyor Belt : trends in human trafficking and smuggling in post-revolution Libya March 2017 A NETWORK TO COUNTER NETWORKS The Human Conveyor Belt : trends in human trafficking and smuggling in post-revolution Libya Mark Micallef March 2017 Cover image: © Robert Young Pelton © 2017 Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Global Initiative. Please direct inquiries to: The Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime WMO Building, 2nd Floor 7bis, Avenue de la Paix CH-1211 Geneva 1 Switzerland www.GlobalInitiative.net Acknowledgments This report was authored by Mark Micallef for the Global Initiative, edited by Tuesday Reitano and Laura Adal. Graphics and layout were prepared by Sharon Wilson at Emerge Creative. Editorial support was provided by Iris Oustinoff. Both the monitoring and the fieldwork supporting this document would not have been possible without a group of Libyan collaborators who we cannot name for their security, but to whom we would like to offer the most profound thanks. The author is also thankful for comments and feedback from MENA researcher Jalal Harchaoui. The research for this report was carried out in collaboration with Migrant Report and made possible with funding provided by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Norway, and benefitted from synergies with projects undertaken by the Global Initiative in partnership with the Institute for Security Studies and the Hanns Seidel Foundation, the United Nations University, and the UK Department for International Development. About the Author Mark Micallef is an investigative journalist and researcher specialised on human smuggling and trafficking. -

International Medical Corps in Libya from the Rise of the Arab Spring to the Fall of the Gaddafi Regime

International Medical Corps in Libya From the rise of the Arab Spring to the fall of the Gaddafi regime 1 International Medical Corps in Libya From the rise of the Arab Spring to the fall of the Gaddafi regime Report Contents International Medical Corps in Libya Summary…………………………………………… page 3 Eight Months of Crisis in Libya…………………….………………………………………… page 4 Map of International Medical Corps’ Response.…………….……………………………. page 5 Timeline of Major Events in Libya & International Medical Corps’ Response………. page 6 Eastern Libya………………………………………………………………………………....... page 8 Misurata and Surrounding Areas…………………….……………………………………… page 12 Tunisian/Libyan Border………………………………………………………………………. page 15 Western Libya………………………………………………………………………………….. page 17 Sirte, Bani Walid & Sabha……………………………………………………………………. page 20 Future Response Efforts: From Relief to Self-Reliance…………………………………. page 21 International Medical Corps Mission: From Relief to Self-Reliance…………………… page 24 International Medical Corps in the Middle East…………………………………………… page 24 International Medical Corps Globally………………………………………………………. Page 25 Operational data contained in this report has been provided by International Medical Corps’ field teams in Libya and Tunisia and is current as of August 26, 2011 unless otherwise stated. 2 3 Eight Months of Crisis in Libya Following civilian demonstrations in Tunisia and Egypt, the people of Libya started to push for regime change in mid-February. It began with protests against the leadership of Colonel Muammar al- Gaddafi, with the Libyan leader responding by ordering his troops and supporters to crush the uprising in a televised speech, which escalated the country into armed conflict. The unrest began in the eastern Libyan city of Benghazi, with the eastern Cyrenaica region in opposition control by February 23 and opposition supporters forming the Interim National Transitional Council on February 27. -

Health Sector Bulletin

HEALTH SECTOR BULLETIN June 2021 Libya Emergency type: Complex Emergency Reporting period: 01.06.2021 to 30.06.2021 Total population People affected People in need People in need Health People in acute Sector health need 7,400,000 2,470,000 1,250,000 1,195,389 1,010,000 PIN (IDP) PIN (Returnees) PIN (Non- PIN (Migrants) PIN (Refugees) displaced) 168,728 180,482 498,908 301,026 46,245 Target Health Required Funded Coverage Sector (US$ m) (US$ m) (%) 450,795 40,990,000 3 7.3 KEY ISSUES 2021 PMR (Periodic Monitoring Report) related indicators Health sector related challenges and obstacles Number of medical procedures provided (including outpatient consultations, Deterioration of security situation in detention referrals, mental health, trauma 32,270 centers in Tripoli consultations, deliveries, physical rehabilitation) Supporting epidemiological and laboratory Number of public health facilities surveillance in Libya supported with health services and 70 commodities Development of national policy and a Number of mobile medical teams/clinics 50 strategic action plan for nursing and (including EMT) midwifery in Libya Number of health service providers and CHW trained through capacity building 333 Health sector assessment registry for quarter and refresher training II 2021 Number of attacks on health care reported 0 Percentage of EWARN sentinel sites 48 Situation with HIV treatment in Libya submitting reports in a timely manner Percentage of disease outbreaks responded 82 Health sector 2021 HRP Periodic Monitoring to within 72 hours of identification Report Number of reporting organizations 13 Percentage of reached districts 91 Impact of the heat wave on health service Percentage of reached municipalities 46 delivery (among functioning health facilities) Percentage of reached municipalities in across the country areas of severity scale higher than 3 13 1 HEALTH SECTOR BULLETIN June 2021 SITUATION OVERVIEW • June 3, the director of Libyan Red Crescent branch in Ejdabia was kidnapped by a group of unknown people. -

Proposed Alternate Electoral Law for Selection of Libya's

Proposed Alternate Electoral Law for Selection of Libya’s Constitutional Assembly Issued by the Libyan Women’s Platform for Peace, in partnership with a coalition of Libyan civil society organizations (Based on and combines Azza Maghur’s , Abdel Qader Qadura’s and Younis Fanoush’s proposals) The Electoral districts shall be divided according to the following: 1.The Eastern District: The Benghazi district, Al-Bayda’ district, Ajdabia district, Darna district, Tobruq district. Each district shall be allocated five seats (four seats for the list and one for the individual). 2. The Western District: 7 seats (6 lists + 1 individual) for Tripoli district, 5 seats (4 lists+ 1 individuals) for Misrata district, 3 seats ( 2 lists + 1 individual) for Sert district, 5 seats ( 4 lists+ 1 individuals) for Zawiyah district. 3.The Southern district: Sabha district. Ubari district. Each district shall be allocated ten seats. (8 seats for the lists and two for the individuals). The election shall be held according to the closed list system. Lists, each of which include five candidates, shall compete according to the mentioned criteria and terms. Any list that does meet such terms shall not be illegible for competition. Those wishing to participate in the election blocs and political entities, individually or collectively within a coalition, may apply through independent lists. The elections shall be carried out according to the absolute majority criterion, hence one integrated list shall win the elections. Should no list win the absolute majority of the votes of the electoral roll (50% + 1) in the first round, a second round shall be held a week after the first round of elections is held. -

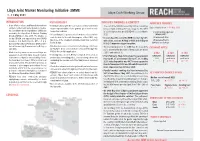

Libya Joint Market Monitoring Initiative (JMMI) Libya Cash Working Group 1 - 11 May 2021

Libya Joint Market Monitoring Initiative (JMMI) Libya Cash Working Group 1 - 11 May 2021 INTRODUCTION METHODOLOGY JMMI KEY FINDINGS & CONTEXT JMMI KEY FIGURES • In an effort to inform cash-based interventions • Field staff familiar with the local market conditions identified • The cost of the MEB increased by 0.5% across Libya Data collection from 1 - 11 May 2021 and better understand market dynamics in Libya, shops representative of the general price level in their between April and May 2021 (see page 2). The MEB the Joint Market Monitoring Initiative (JMMI) was respective locations. is 12.3% higher than pre-COVID-19 levels in March 2 participating agencies created by the Libya Cash & Markets Working • At least four prices per assessed item were collected within 2020. (REACH, WFP) Group (CMWG) in June 2017. The initiative is each location. In line with the purpose of the JMMI, only 32 assessed cities led by REACH and supported by the CMWG • In east Libya, the cost of the MEB has risen by 5.4% the price of the cheapest available brand was recorded 45 assessed items members. It is funded by the Office of U.S. with cities, such as Al Marj (+14.9) and Al Bayda 634 assessed shops Bureau of Humanitarian Assistance (BHA) and the for each item. (+10.2%) experiencing price spikes. • Enumerators were trained on methodology and tools United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees • The food proportion of the MEB has decreased by EXCHANGE RATES1 (UNHCR). by REACH. Data collection was conducted through the 8.2%, driven by the decrease of items, such as onions KoBoCollect mobile application. -

Pdf | 194.16 Kb

WHO Libya biweekly operational update 1-15 January 2021 General developments: political & security situation • Guterres announces necessary steps for Libya ceasefire to hold, • The Libyan financial committee tasked with devising the 2021 unified budget of the country held a meeting in eastern Libyan town of Brega in the presence of officials from the Tripoli-based Government of National Accord. • Libyan GNA, Haftar's forces swap over 35 prisoners. • Italy appoints special envoy to Libya. • NATO Reaffirms Support To Libya And Concern About The Russian Presence. • LPDF's Advisory Committee meeting kicked off today in the Palais Des Nations in Geneva. • Libyan Economic Dialogue Meets to Follow up on Critical Economic Reforms. • Acting Special Representative of the Secretary-General Stephanie Williams announces the establishment of the LPDF's Advisory Committee. • The US Ambassador to Libya, Richard Norland has said that members of the Libyan Political Dialogue Forum (LPDF) Advisory Committee (AC) had been offered an opportunity to forge consensus on forming a new government. • Health workers call for urgent measures, say conditions in Health Ministry are catastrophic. OPERATIONAL UPDATES COVID-19 Pillar 1: Country‑level coordination, planning and monitoring • Facilitated the production of the first COVID-19 national strategy based on the outcomes of the national workshop on 11 November 2020. • Participated in the in the regular meetings and provide technical support to the COVID-19 advisory committee in Sabha • Worked with the University of Benghazi in preparing the COVID-19 scientific conference on 30th January 2021. • Met with the Supreme COVID-19 Committee in Benghazi, discussed 2021 procurement plan for COVID-19 diagnostic equipment, updated partners about the COVID-19 situation in Libya. -

Overview of the International Health Sector Support to Public Health Facilities | Libya January to July 2021

Overview of the International Health Sector Support to public health facilities | Libya January to July 2021 Health Sector Libya, September 2021 Contents 1) Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 2 2) Nation-wide analysis ................................................................................................................. 2 2.1) Kinds of support .................................................................................................................... 4 3) District based analysis: .............................................................................................................. 5 3.1) Support by Organization ....................................................................................................... 6 3.2) Kinds of support .................................................................................................................... 7 Annex-I | List of Organizations per their supported public health facilities: ..................................... 9 Annex-II | List of provided support by type, at a district level ......................................................... 10 Health Sector | Libya Page 1 of 10 1) Introduction This report provides analysis of the delivered assistance by international health sector partners to the MoH public health facilities in Libya, from January to July 2021. A standardized template was designed and shared with sector partners to assess different types of -

Incidence of Cystic Echinococcosis in Libya: I. Seroprevalence of Hydatid Disease in Sheep and Goats Naturally Exposed to the Infection in the North Midland Region

American Journal of Animal and Veterinary Sciences s Original Research Paper Incidence of Cystic Echinococcosis in Libya: I. Seroprevalence of Hydatid Disease in Sheep and Goats Naturally Exposed to the Infection in the North Midland Region 1Mohamed M. Ibrahem, 2Badereddin B. Annajar and 3Wafa M. Ibrahem 1Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, University of Zawia, P.O. Box 16418, Zawia, Libya 2National Centre for Disease Control, Ain Zara, P.O. Box 71171, Tripoli, Libya 3Department of Parasitology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Zawia, P.O. Box 16418, Zawia, Libya Article history Abstract: Hydatid disease is one of the most and serious public health and Received: 28-05-2016 veterinary problems in Libya and other North African countries. Thirteen Revised: 28-09-2016 rural villages of two main districts bordered to each other at the north Accepted: 27-10-2016 midland of the country namely, Misrata which is almost agricultural area and about 200 km east of Tripoli and Sirt which is almost pasture area and Corresponding Author: Mohamed M. Ibrahem about 500 km east of Tripoli, were included in the current study. Incidence Department of Zoology, of cystic echinococcosis was investigated serologically using serum Faculty of Science, University samples collected from 2651 animals of three groups; young sheep under of Zawia, P.O. Box 16418, two years old (240), adult sheep over two years old (2082) and adult goats Zawia, Libya over two years old (329). Antigen B prepared from camel crude hydatid Email: [email protected] cyst fluid together with ELISA were used for detection of total IgG antibodies against hydatid cysts in the collected serum samples.