Field-Marshal Albert Kesselring in Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How the Luftwaffe Lost the Battle of Britain British Courage and Capability Might Not Have Been Enough to Win; German Mistakes Were Also Key

How the Luftwaffe Lost the Battle of Britain British courage and capability might not have been enough to win; German mistakes were also key. By John T. Correll n July 1940, the situation looked “We shall fight on the beaches, we shall can do more than delay the result.” Gen. dire for Great Britain. It had taken fight on the landing grounds, we shall Maxime Weygand, commander in chief Germany less than two months to fight in the fields and in the streets, we of French military forces until France’s invade and conquer most of Western shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender, predicted, “In three weeks, IEurope. The fast-moving German Army, surrender.” England will have her neck wrung like supported by panzers and Stuka dive Not everyone agreed with Churchill. a chicken.” bombers, overwhelmed the Netherlands Appeasement and defeatism were rife in Thus it was that the events of July 10 and Belgium in a matter of days. France, the British Foreign Office. The Foreign through Oct. 31—known to history as the which had 114 divisions and outnumbered Secretary, Lord Halifax, believed that Battle of Britain—came as a surprise to the Germany in tanks and artillery, held out a Britain had lost already. To Churchill’s prophets of doom. Britain won. The RAF little longer but surrendered on June 22. fury, the undersecretary of state for for- proved to be a better combat force than Britain was fortunate to have extracted its eign affairs, Richard A. “Rab” Butler, told the Luftwaffe in almost every respect. -

Volume 7, Issue 2, July 2021 Introduction: New Researchers and the Bright Future of Military History

www.bjmh.org.uk British Journal for Military History Volume 7, Issue 2, July 2021 Cover picture: Royal Navy destroyers visiting Derry, Northern Ireland, 11 June 1933. Photo © Imperial War Museum, HU 111339 www.bjmh.org.uk BRITISH JOURNAL FOR MILITARY HISTORY EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD The Editorial Team gratefully acknowledges the support of the British Journal for Military History’s Editorial Advisory Board the membership of which is as follows: Chair: Prof Alexander Watson (Goldsmiths, University of London, UK) Dr Laura Aguiar (Public Record Office of Northern Ireland / Nerve Centre, UK) Dr Andrew Ayton (Keele University, UK) Prof Tarak Barkawi (London School of Economics, UK) Prof Ian Beckett (University of Kent, UK) Dr Huw Bennett (University of Cardiff, UK) Prof Martyn Bennett (Nottingham Trent University, UK) Dr Matthew Bennett (University of Winchester, UK) Prof Brian Bond (King’s College London, UK) Dr Timothy Bowman (University of Kent, UK; Member BCMH, UK) Ian Brewer (Treasurer, BCMH, UK) Dr Ambrogio Caiani (University of Kent, UK) Prof Antoine Capet (University of Rouen, France) Dr Erica Charters (University of Oxford, UK) Sqn Ldr (Ret) Rana TS Chhina (United Service Institution of India, India) Dr Gemma Clark (University of Exeter, UK) Dr Marie Coleman (Queens University Belfast, UK) Prof Mark Connelly (University of Kent, UK) Seb Cox (Air Historical Branch, UK) Dr Selena Daly (Royal Holloway, University of London, UK) Dr Susan Edgington (Queen Mary University of London, UK) Prof Catharine Edwards (Birkbeck, University of London, -

The Historical Journal VIA RASELLA, 1944

The Historical Journal http://journals.cambridge.org/HIS Additional services for The Historical Journal: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here VIA RASELLA, 1944: MEMORY, TRUTH, AND HISTORY JOHN FOOT The Historical Journal / Volume 43 / Issue 04 / December 2000, pp 1173 1181 DOI: null, Published online: 06 March 2001 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0018246X00001400 How to cite this article: JOHN FOOT (2000). VIA RASELLA, 1944: MEMORY, TRUTH, AND HISTORY. The Historical Journal, 43, pp 11731181 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/HIS, IP address: 144.82.107.39 on 26 Sep 2012 The Historical Journal, , (), pp. – Printed in the United Kingdom # Cambridge University Press REVIEW ARTICLE VIA RASELLA, 1944: MEMORY, TRUTH, AND HISTORY L’ordine eZ giaZ stato eseguito: Roma, le Fosse Ardeatine, la memoria. By Alessandro Portelli. Rome: Donzelli, . Pp. viij. ISBN ---.L... The battle of Valle Giulia: oral history and the art of dialogue. By A. Portelli. Wisconsin: Wisconsin: University Press, . Pp. xxj. ISBN ---.$.. [Inc.‘The massacre at Civitella Val di Chiana (Tuscany, June , ): Myth and politics, mourning and common sense’, in The Battle of Valle Giulia, by A. Portelli, pp. –.] Operazione Via Rasella: veritaZ e menzogna: i protagonisti raccontano. By Rosario Bentivegna (in collaboration with Cesare De Simone). Rome: Riuniti, . Pp. ISBN -- -.L... La memoria divisa. By Giovanni Contini. Milan: Rizzoli, . Pp. ISBN -- -.L... Anatomia di un massacro: controversia sopra una strage tedesca. By Paolo Pezzino. Bologna: Il Mulino, . Pp. ISBN ---.L... Processo Priebke: Le testimonianze, il memoriale. Edited by Cinzia Dal Maso. -

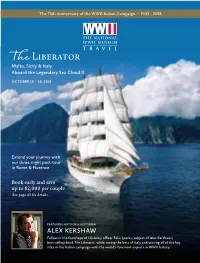

Alex Kershaw

The 75th Anniversary of the WWII Italian Campaign • 1943 - 2018 The Liberator Malta, Sicily & Italy Aboard the Legendary Sea Cloud II OCTOBER 19 – 28, 2018 Extend your journey with our three-night post-tour in Rome & Florence Book early and save up to $2,000 per couple See page 43 for details. FEATURING AUTHOR & HISTORIAN ALEX KERSHAW Follow in the footsteps of US Army officer Felix Sparks, subject of Alex Kershaw’s best-selling book The Liberator, while seeing the best of Italy and visiting all of the key sites in the Italian campaign with the world's foremost experts in WWII history. Dear friend of the Museum and fellow traveler, t is my great delight to invite you to travel with me and my esteemed colleagues from The National WWII Museum on an epic voyage of liberation and wonder – Ifrom the ancient harbor of Valetta, Malta, to the shores of Italy, and all the way to the gates of Rome. I have written about many extraordinary warriors but none who gave more than Felix Sparks of the 45th “Thunderbird” Infantry Division. He experienced the full horrors of the key battles in Italy–a land of “mountains, mules, and mud,” but also of unforgettable beauty. Sparks fought from the very first day that Americans landed in Europe on July 10, 1943, to the end of the war. He earned promotions first as commander of an infantry company and then an entire battalion through Italy, France, and Germany, to the hell of Dachau. His was a truly awesome odyssey: from the beaches of Sicily to the ancient ruins at Paestum near Salerno; along the jagged, mountainous spine of Italy to the Liri Valley, overlooked by the Abbey of Monte Cassino; to the caves of Anzio where he lost his entire company in what his German foes believed was the most savage combat of the war–worse even than Stalingrad. -

Bombing of Gernika

BIBLIOTECA DE The Bombing CULTURA VASCA of Gernika The episode of Guernica, with all that it The Bombing ... represents both in the military and the G) :c moral order, seems destined to pass 0 of Gernika into History as a symbol. A symbol of >< many things, but chiefly of that Xabier lruio capacity for falsehood possessed by the new Machiavellism which threatens destruction to all the ethical hypotheses of civilization. A clear example of the ..e use which can be made of untruth to ·-...c: degrade the minds of those whom one G) wishes to convince. c., '+- 0 (Foreign Wings over the Basque Country, 1937) C> C: ISBN 978-0-9967810-7-7 :c 90000 E 0 co G) .c 9 780996 781077 t- EDITORIALVASCA EKIN ARGITALETXEA Aberri Bilduma Collection, 11 Ekin Aberri Bilduma Collection, 11 Xabier Irujo The Bombing of Gernika Ekin Buenos Aires 2021 Aberri Bilduma Collection, 11 Editorial Vasca Ekin Argitaletxea Lizarrenea C./ México 1880 Buenos Aires, CP. 1200 Argentina Web: http://editorialvascaekin- ekinargitaletxea.blogspot.com Copyright © 2021 Ekin All rights reserved First edition. First print Printed in America Cover design © 2021 JSM ISBN first edition: 978-0-9967810-7-7 Table of Contents Bombardment. Description and types 9 Prehistory of terror bombing 13 Coup d'etat: Mussolini, Hitler, and Franco 17 Non-Intervention Committee 21 The Basque Country in 1936 27 The Basque front in the spring of 1937 31 Everyday routine: “Clear day means bombs” 33 Slow advance toward Bilbao 37 “Target Gernika” 41 Seven main reasons for choosing Gernika as a target 47 The alarm systems and the antiaircraft shelters 51 Typology and number of airplanes and bombs 55 Strategy of the attack 59 Excerpts from personal testimonies 71 Material destruction and death toll 85 The news 101 The lie 125 Denial and reductionism 131 Reconstruction 133 Bibliography 137 I can’t -it is impossible for me to give any picture of that indescribable tragedy. -

Preparatory Document

Preparatory document Please notice that we recommend that you read the first ten pages of the first three documents, the last document is optional. • International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, Recognizing and Countering Holocaust Distortion: Recommendations for Policy and Decision Makers (Berlin: International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, 2021), read esp. pp. 14-24 • Deborah Lipstadt, "Holocaust Denial: An Antisemitic Fantasy," Modern Judaism 40:1 (2020): 71-86 • Keith Kahn Harris, "Denialism: What Drives People to Reject the Truth," The Guardian, 3 August 2018, as at https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/aug/03/denialism-what-drives- people-to-reject-the-truth (attached as pdf) • Optional reading: Giorgio Resta and Vincenzo Zeno-Zencovich, "Judicial 'Truth' and Historical 'Truth': The Case of the Ardeatine Caves Massacre," Law and History Review 31:4 (2013): 843- 886 Holocaust Denial: An Antisemitic Fantasy Deborah Lipstadt Modern Judaism, Volume 40, Number 1, February 2020, pp. 71-86 (Article) Published by Oxford University Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/750387 [ Access provided at 15 Feb 2021 12:42 GMT from U S Holocaust Memorial Museum ] Deborah Lipstadt HOLOCAUST DENIAL: AN ANTISEMITIC FANTASY* *** When I first began working on the topic of Holocaust deniers, colleagues would frequently tell me I was wasting my time. “These people are dolts. They are the equivalent of flat-earth theorists,” they would insist. “Forget about them.” In truth, I thought the same thing. In fact, when I first heard of Holocaust deniers, I laughed and dismissed them as not worthy of serious analysis. Then I looked more closely and I changed my mind. -

9900 $8900 $8900

Sale 2015 A-R 1-800-786-6210 Prices good through July 31, 2015 $ 00 $ 00 99Black Each 89Green Each M-35 German Combat Helmet Made from heavy gauge mild steel, our "Stahlhelm" helmets feature all of the important details, including rolled shell edges, correct type separately applied air vents, and proper original markings. The genuine leather M-31 liners are attached with 3 split-rivets and include correct leather chinstraps and buckles. Painted in proper green or black color, each helmet comes with a FREE set of decals of your choice. Available in 2 liner & shell sizes that will fit most heads. Great for reenactors and collectors alike! 0102-009-358 Green - Size 57/58 0102-009-360 Green - Size 59/60 0102-009-758 Black - Size 57/58 0102-009-760 Black - Size 59/60 WWI German Stahlhelm and Cut-Out Helmet Our helmet maker is now producing these nice quality replicas of the World War I German Stahlhelm. These accurate reproductions feature rolled rims and the well-known vent lugs on each side, and are fitted with the correct style, 3-piece padded liners and 2-piece leather chinstrap of that period. Paint color is dark green and they are available in large size, which fits up to about size 60.The M-16 is the standard style while the M-18 features ear cut- outs and was also known as the “telephone operator” or “cavalry helmet” A 0102-010-260 M-18 "Cut-Out" B 0102-010-160 M-16 " "Stahlhelm" $ 00 89Each A B General Field Marshall Formal Batons - Museum Quality These exquisite pieces are museum grade copies of the formal baton, or Marschallstab, presented to Field Marshals Erwin Rommel and Erhard Milch upon promotion to Generalfeldmarschall. -

WHO's WHO in the WAR in EUROPE the War in Europe 7 CHARLES DE GAULLE

who’s Who in the War in Europe (National Archives and Records Administration, 342-FH-3A-20068.) POLITICAL LEADERS Allies FRANKLIN DELANO ROOSEVELT When World War II began, many Americans strongly opposed involvement in foreign conflicts. President Roosevelt maintained official USneutrality but supported measures like the Lend-Lease Act, which provided invaluable aid to countries battling Axis aggression. After Pearl Harbor and Germany’s declaration of war on the United States, Roosevelt rallied the country to fight the Axis powers as part of the Grand Alliance with Great Britain and the Soviet Union. (Image: Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-128765.) WINSTON CHURCHILL In the 1930s, Churchill fiercely opposed Westernappeasement of Nazi Germany. He became prime minister in May 1940 following a German blitzkrieg (lightning war) against Norway, Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. He then played a pivotal role in building a global alliance to stop the German juggernaut. One of the greatest orators of the century, Churchill raised the spirits of his countrymen through the war’s darkest days as Germany threatened to invade Great Britain and unleashed a devastating nighttime bombing program on London and other major cities. (Image: Library of Congress, LC-USW33-019093-C.) JOSEPH STALIN Stalin rose through the ranks of the Communist Party to emerge as the absolute ruler of the Soviet Union. In the 1930s, he conducted a reign of terror against his political opponents, including much of the country’s top military leadership. His purge of Red Army generals suspected of being disloyal to him left his country desperately unprepared when Germany invaded in June 1941. -

“Wars Should Be Fought in Better Country Than This” the First Special Service Force in the Italian Mountains by Kenneth Finlayson

“Wars should be fought in better country than this” The First Special Service Force in the Italian Mountains by Kenneth Finlayson 48 Veritas eavy fighting raged across the summit of Monte La Canadian-American infantry unit of World War II. Defensa. The First Special Service Force (FSSF) was Activated on 20 July 1942 at Fort William Henry Harrison, decisively engaged with the German defenders on near Helena, Montana, the FSSF was originally intended H 2 the mountain. LTC Ralph W. Becket, commanding 1st for a special mission in Norway. Operation PLOUGH Battalion of the First Regiment, witnessed the assault was designed to destroy the Norwegian hydroelectric of a Second Regiment platoon against a German dam at Vermork that was producing deuterium, the machine gun position. 1LT Maurice Le Bon led his men “heavy water” vital to the German nuclear program.3 The to a concealed position 30 yards from the flank of the cancellation of PLOUGH resulted in the FSSF being sent enemy. “I watched all this develop, not missing a thing. first to the Aleutians and then to the Mediterranean. When our machine guns and mortars opened fire from It was in southern Italy that the Force first saw combat. the right, the enemy replied with strong machine gun The Force’s reputation as an elite unit was made during and Schmeisser pistol fire,” said Becket. “Suddenly our the U.S. Fifth Army’s grueling campaign to break through fire stopped and for the first and only time I heard the the German Winter Line south of Rome. This article will order – in Le Bon’s strong French-Canadian accent– ‘Fix look at the two phases of this operation and show how bayonets!’ A moment later Le Bon emerged into the the bloody fighting in the mountains of Italy had a deep clearing with his section and the men, with bayonets and lasting impact on the unit. -

Observations on the Air War in Syria Lt Col S

Views Observations on the Air War in Syria Lt Col S. Edward Boxx, USAF His face was blackened, his clothes in tatters. He couldn’t talk. He just point- ed to the flames, still about four miles away, then whispered: “Aviones . bombas” (planes . bombs). —Guernica survivor iulio Douhet, Hugh Trenchard, Billy Mitchell, and Henry “Hap” Arnold were some of the greatest airpower theorists in history. Their thoughts have unequivocally formed the basis of G 1 modern airpower. However, their ideas concerning the most effective use of airpower were by no means uniform and congruent in their de- termination of what constituted a vital center with strategic effects. In fact the debate continues to this day, and one may draw on recent con- flicts in the Middle East to make observations on the topic. Specifi- cally, this article examines the actions of one of the world’s largest air forces in a struggle against its own people—namely, the rebels of the Free Syrian Army (FSA). As of early 2013, the current Syrian civil war has resulted in more than 60,000 deaths, 2.5 million internally displaced persons, and in ex- cess of 600,000 refugees in Turkey, Jordan, Iraq, and Lebanon.2 Presi- dent Bashar al-Assad has maintained his position in part because of his ability to control the skies and strike opposition targets—including ci- vilians.3 The tactics of the Al Quwwat al-Jawwiyah al Arabiya as- Souriya (Syrian air force) appear reminiscent of those in the Spanish Civil War, when bombers of the German Condor Legion struck the Basque market town of Guernica, Spain, on 26 April 1937. -

Battle of Anzio Timeline

https://ww2db.com/battle_spec.php ?battle_id=313 Battle of Anzio Timeline 18 Dec 1943 The plan to land several divisions at Anzio, Italy was briefly canceled. g_2 Jan 1944 36,000 Allied troops landed at Anzio, Italy, facing little opposition. 23 Jan 1944 The destroyer HMS Janus was lost off Anzio, Italy. (24 Jan 1944 German forces in the Anzio, Italy region increased to over 40,000 men. 25 Jan 1944 General Eberhard von Mackensen assumed overall control of forces in the Anzio, Italy area. 27 Jan 1944 To the west, Allied Major General John Lucas by now commanded 70,000 men, 237 tanks, 508 heavy guns, and 27,000 tons of supplies at Anzio, Italy, but he decided to still maintain a defensive posture. 28 Jan 1944 German Field Marshal Albert Kesselring ordered a counterattack against the Allied beachhead at Anzio, Italy. 9 Jan 1944 Total Allied strength at the Anzio, Italy beachhead totaled 69,000 men, 508 guns, and 208 tanks by the end of this day. On the other side of the lines, German strength rose to 71,500 men. 30 Jan 1944 Allied forces attacked out of the Anzio, Italy beachhead, advancing toward Cisterna and Campoleone, but none of the two forces would be able to capture the objectives; during the process, an entire US Army Ranger battalion was destroyed. 2 Feb 1944 Germans defeated American troops in the Battle of Cisterna near Anzio, Italy. 3 Feb 1944 The American attempt to break out of the Anzio beachhead in Italy was halted, followed by the first German counterattack against the beachhead. -

Milch Casefertig.Rtf

TRIALS OF WAR CRIMINALS BEFORE THE NUERNBERG MILITARY TRIBUNALS UNDER CONTROL COUNCIL LAW No. 10 VOLUME II NUERNBERG OCTOBER 1946-APRIL 1949 ________ For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - Price $2.75 (Buckram "The Milch Case " CASE NO. 2 MILITARY TRIBUNAL NO. II THE UNITED STATES OP AMERICA —against — ERHARD MILCH VII.JUDGMENT........................................................................................................................ 5 A. Opinion and Judgment of the United States Military Tribunal II* ................................... 5 COUNT TWO.................................................................................................................... 5 COUNT ONE..................................................................................................................... 9 COUNT THREE .............................................................................................................. 18 SENTENCE ............................................................................................................................. 22 B. Concurring Opinion by Judge Michael A. Musmanno.................................................... 23 COUNT ONE................................................................................................................... 23 COUNT TWO.................................................................................................................. 23 COUNT THREE .............................................................................................................